The United Nations (UN) Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (the CRPD) is an international treaty that was adopted in 2006 to help protect the rights of people with disabilities around the world. Canada and 183 other states parties have accepted the legal obligations contained in the CRPD.

These obligations include ensuring there are national laws to prevent discrimination, eliminating barriers to accessibility, and working to promote the capabilities and contributions of people with disabilities.

The CRPD also includes processes to make sure that countries are meeting these obligations. Canada and other countries must regularly report to the UN Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities to explain what they are doing to make sure that people with disabilities can fully exercise their rights. In Canada, the Canadian Human Rights Commission also monitors how well Canada is implementing the CRPD.

Canada and 99 other states parties have also signed on to the Optional Protocol to the CRPD. The Optional Protocol creates a process for people to make complaints directly to the UN Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.

Many Canadians who live with disabilities face discrimination and other challenges in fully accessing their rights. People with disabilities are also more likely to experience homelessness, poverty and imprisonment. Some population groups, including Indigenous peoples, face higher rates of disabilities and are also more likely to face discrimination.

To remedy some of these issues, governments in Canada have taken steps to improve accessibility and inclusion for people with disabilities. For example, the Accessible Canada Act aims to improve the way that the Government of Canada and organizations within federal jurisdiction address accessibility and interact with Canadians with disabilities. The CRPD helps to keep Canada and other countries on track in upholding and advancing the rights of people with disabilities.

The United Nations (UN) Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD, or the Convention) and its accompanying Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (Optional Protocol) were welcomed by many states, civil society organizations, members of the disability community and other commentators when they were adopted by the UN General Assembly on 13 December 2006.1 The Convention was groundbreaking for the manner in which it was drafted, adopted and signed. It was completed in less time than any of the other core international human rights treaties and obtained a record number of signatories when it opened for signature. Furthermore, it was negotiated with the involvement of many groups, including non‑governmental and international organizations, and national human rights institutions.

Unlike many earlier international treaties that simply set out the rights recognized by the UN, the CRPD outlines key steps and actions for states parties to take in order to promote and protect the human rights of people with disabilities.2 The CRPD built on existing reporting and monitoring models from other treaties while also seeking to develop more dynamic participation with civil society and closer monitoring by independent mechanisms. As described in a 2011 joint paper by the Council of Canadians with Disabilities and the Canadian Association for Community Living (now known as Inclusion Canada), the CRPD is "a tool that helps communities and governments understand why and how the rights of people with disabilities haven't been realized and it provides a framework that articulates the conditions needed to make rights a reality."3

The Optional Protocol also provides individuals and groups with a procedure to register complaints about violations of their rights under the Convention. Further, the reporting and monitoring processes under the Convention, along with the assessments made by non‑governmental organizations, UN bodies and other states parties, provide broader opportunities to discuss progress being made and any ongoing concerns. Canada's first report to the UN Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities was delivered in 2014. A combined second and third report is scheduled to be delivered in 2022.4 This HillStudy explains how the Convention was developed, reviews its key principles and obligations, and provides an overview of its implementation in Canada.

The CRPD does not recognize new rights per se, nor is it the only international instrument to address issues pertaining to disabilities.5 In 1975, the UN Declaration on the Rights of Disabled Persons formally recognized that persons with disabilities are entitled to the same rights as others.6 Other treaties, such as the Convention on the Rights of the Child, specifically mention that the rights articulated within them apply more broadly to persons with disabilities, while still others, such as the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, state that they apply universally to all persons.7

However, ongoing discrimination against persons with disabilities and the lack of widespread, explicit recognition of their rights prompted the UN and its members to recognize that existing protections granted by these instruments were insufficient. A number of international organizations, such as the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) and the Inter‑Parliamentary Union, acknowledged that persons with disabilities remained one of the most disadvantaged and marginalized population groups in society.8 There was a need for an instrument that could better articulate how recognized civil, cultural, economic, political and social rights operate within a disability context, and that would outline the obligations that states have to protect and promote these rights.9

Moreover, the Convention emerged in the context of growing recognition that people with disabilities comprise a significant proportion of the world's population. According to the World Health Organization's most recent data (from 2010), over one billion people – about 15% of the world's population – live with some form of disability, and up to 190 million people have very significant difficulties in functioning. The number of people with some form of disability is increasing as the world population grows and ages.10

In developing a convention that would be meaningful across jurisdictions, obligations were included that would promote the rights of persons with disabilities in different national contexts and the recognition of the importance of international cooperation.11 For example, the resources available to a country may affect the nature of the challenges faced by persons with disabilities and the country's ability to invest in programs and infrastructure to address those challenges. In developing countries, the UN Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization estimates that 90% of children with disabilities do not attend school.12

The development of a convention also had to respond to the types of discrimination faced by persons with disabilities, which include both individual and systemic discrimination. Individual discrimination arises from the actions and choices of the people whom persons with disabilities encounter in their daily lives, while systemic discrimination occurs when discriminatory choices are institutionalized in laws and policies. As noted by the OHCHR, for persons with disabilities to fully achieve a substantive level of equality around the world, laws that limit their rights need to be replaced. These laws, which institutionalize systemic discrimination, include

immigration laws that prohibit entry to a country based on disability; laws that prohibit persons with disabilities to marry; laws that allow the administration of medical treatment to persons with disabilities without their free and informed consent; [and] laws that allow detention on the basis of mental or intellectual disability.13

Finally, the development of the Convention reflected a need for a more inclusive approach for persons with disabilities and civil society organizations in the assertion and monitoring of their rights. As stated by the OHCHR, "[p]ersons with disabilities have historically been invisible in the human rights system and have been overlooked in human rights work."14

The recognized need for legislative and policy reform, and the need to change prevailing attitudes that focus too often on how to fix a person's disability rather than on how society can remove barriers impeding their participation, contributed to the quick progress made in drafting and adopting the Convention.15

The UN General Assembly set up an ad hoc committee in December 2001 that considered proposals and held sessions to negotiate the content of the Convention.16 These negotiations were completed in just three years – less time than any of the other core international human rights treaties – and involved not only governments but also non‑governmental organizations, international organizations and national human rights institutions.17

The Convention and its Optional Protocol were adopted on 13 December 2006 during the 61st session of the UN General Assembly. The Convention opened for signature at the UN headquarters in New York on 30 March 2007 and came into force on 3 May 2008. When the Convention and its Optional Protocol were opened for signature, a record number of UN member states signed them.18 As of 2021, there were 184 parties to the CRPD and 100 parties to the Optional Protocol.19

Article 1 of the CRPD states that the Convention's main purpose is "to promote, protect and ensure the full and equal enjoyment of all human rights and fundamental freedoms by all persons with disabilities, and to promote respect for their inherent dignity."20

The Convention reaffirms a broad number of existing human rights recognized by the UN and elaborates upon them within the context of disability issues. It reiterates such basic rights as the freedom of expression and opinion (Article 21), freedom from torture (Article 15) and the rights to life, liberty and security of the person (Articles 10 and 14). It provides direction to states parties on steps they must take to ensure that people with disabilities share the same rights as others. It clarifies the types of actions that states parties should take to promote and protect the rights of persons with disabilities in such areas as freedom of expression and opinion, respect for home and the family, education, health, employment and access to services.

By ratifying the CRPD, a country commits to ensuring that its domestic laws fully implement the Convention's legal obligations.21 The obligations range from general to specific. The general obligations require states parties to take whatever appropriate measures are required to ensure that the rights contained in the Convention are properly protected and promoted. Other general obligations include adopting legislation to abolish discrimination (Article 4); encouraging research and development in accessible goods, services and technology for persons with disabilities (Article 4); and promoting international cooperation among states parties, international and regional organizations and civil society (Article 32).

The more specific obligations in the Convention indicate what actions should be taken to promote its main principles. For instance, Article 8 of the Convention begins with a general obligation for states parties to raise awareness about persons with disabilities generally, to promote their capabilities and contributions, to foster respect for their rights, and to combat stereotypes and harmful practices. It then specifies that such measures may include public education campaigns.

The 1975 UN Declaration on the Rights of Disabled Persons (the Declaration) defined a "disabled person" as anyone "unable to ensure by himself or herself, wholly or partly, the necessities of a normal individual and/or social life, as a result of deficiency, either congenital or not, in his or her physical or mental capabilities."22 This definition stresses the inabilities of persons with disabilities and their dependence on assistance. Since the Declaration was adopted, attitudes towards disability have shifted. For instance, the term "disabled person" has been largely replaced in common use by "persons with disabilities," since the latter places emphasis on the person rather than on the disability.

Although the CRPD uses the term "persons with disabilities," it is not included in the definitions section. The absence of a formal definition reflects the fact that there are different conceptualizations of disability, and recognizes, as noted in the preamble, that "disability" is an "evolving concept."23 To provide some guidance, however, the Convention states in its "Purpose" section that the term "persons with disabilities" includes "those who have long‑term physical, mental, intellectual or sensory impairments which in interaction with various barriers may hinder their full and effective participation in society on an equal basis with others" (Article 1). This wording recognizes the diverse types of disabilities, or "impairments," that a person may have. Perhaps most importantly, it emphasizes that a person with a disability is only limited in their ability to participate in society as a result of their interaction with barriers that society permits to exist, which may be physical obstacles, policies, legislation, or discriminatory behaviour and prejudicial attitudes.24 The Convention requires states parties to identify and eliminate these obstacles and barriers.25

This language is also reflective of the rights‑based approach, which views persons with disabilities as rights holders and active members of society.

Since the Convention is intended to ensure that persons with disabilities enjoy access to human rights free from discrimination, the importance of equality is stressed throughout. The general principles meant to guide the interpretation of the Convention, as enumerated in Article 3, include "[f]ull and effective participation and inclusion in society," "[e]quality of opportunity" and "[e]quality between men and women." The Convention addresses many areas where persons with disabilities have traditionally been discriminated against, including access to justice, participation in political, cultural and public life, education, and employment.26

Legal equality is a fundamental right that ensures individuals are empowered to access justice and challenge the violation of any of their rights. The Convention states that "all persons are equal before and under the law and are entitled without any discrimination to the equal protection and equal benefit of the law" (Article 5). States parties must also ensure that persons with disabilities have access to justice on an equal basis with others (Article 13), including by ensuring that appropriate accommodations are made to facilitate their participation in all legal proceedings (including as a trial witness, complainant or defendant).

Article 12 uses similar language to Article 5 but adds that persons with disabilities are entitled to equal recognition before the law. This provision also includes an important development not seen in previous UN instruments. It focuses on ensuring that persons with disabilities can exercise their own legal capacity and that the state provides support as necessary to allow them to do so. The intention here is that persons with disabilities are to be supported in making their own decisions concerning their personal, financial or legal affairs and that their best interests are always to be considered by those assisting them.

As summarized by the ARCH Disability Law Centre, "the Convention focuses not on whether a person has capacity to make decisions, but upon how that person can be assisted so that he or she is able to make decisions affecting their life."27 Article 12 also adds that persons with disabilities should have an equal opportunity to own and possess property, control their own financial affairs and participate in all decisions affecting them. It further requires that states parties have sufficient legal safeguards to protect this equal legal capacity from being abused, such as through the review of important legal decisions by an impartial authority or judicial body.

Article 2 of the CRPD covers another aspect of ensuring substantive equality for persons with disabilities by requiring that states parties promote the principle of reasonable accommodation of persons with disabilities. In brief, this is a duty imposed on public and private employers, service providers and landlords to ensure that their policies, programs, infrastructure or operations do not have a discriminatory effect and do not prevent persons with disabilities from fully enjoying and exercising their rights.28 If they do, then the duty holder is obligated to undertake any reasonable modifications or adjustments that do not impose an undue burden or hardship in order to provide accommodation to the person seeking it.

The Convention also seeks to address the complexity of the inequalities individuals face in society by noting in the preamble that many persons with disabilities face "multiple or aggravated forms of discrimination" on the basis of sex, age, ethnicity, religion or other grounds. Articles 6 and 7 place special emphasis on the need for states parties to recognize the rights of women and children with disabilities and for states parties to take the "necessary" or "appropriate" measures to ensure they enjoy all human rights and fundamental freedoms.

The importance of accessibility is emphasized throughout the Convention. It is included as one of the eight general principles set out in Article 3. Obligations surrounding accessibility require states parties to ensure access in such areas as justice (Article 13), education (Article 24), health (Article 25), and work and employment (Article 27). Article 9 articulates the key areas where accessibility is to be promoted and barriers and obstacles eliminated, including transportation, information and communications, and other facilities and services open or provided to the public, whether operated by the private or public sector. Article 9 also requires that states parties not only develop minimum standards for the accessibility of facilities and services but also "[p]romote the design, development, production and distribution of accessible information and communications technologies and systems at an early stage, so that these technologies and systems become accessible at minimum cost."

Article 28 is an important guarantee for persons with disabilities of an adequate standard of living and social protection, including through access to such necessities as clean water, affordable services and supports for disability‑related needs, housing, poverty reduction and social protection programs, and assistance to families for disability‑related expenses.

Removing the barriers that impede persons with disabilities means more than simply making places and services accessible. It also means making sure that persons with disabilities are not impeded from "[f]ull and effective participation and inclusion in society" (Article 3). To promote inclusion, states parties must consult and actively involve persons with disabilities in "the development and implementation of legislation and policies to implement the present Convention, and in other decision‑making processes concerning issues relating to persons with disabilities" (Article 4.3).

To guarantee this active participation, Article 29 of the CRPD focuses on political and public life, including protecting the rights to vote and to participate in the conduct of public affairs (including via organizations representing persons with disabilities). Article 30 affirms that persons with disabilities have the same rights as others to participate in and enjoy sports, the arts and other cultural activities. On one level, this provision is intended to ensure that such sites as theatres, museums, libraries, sport venues and children's playgrounds, as well as such materials as books, films and recordings, are accessible to everyone. It goes further, however, and requires that states parties take active steps to enable persons with disabilities "to have the opportunity to develop and utilize their creative, artistic and intellectual potential, not only for their own benefit, but also for the enrichment of society" and to "participate in disability‑specific sporting and recreational activities" (Article 30.5).29

The Convention has been designed to ensure not only that the treaty is properly implemented by a state but also that there is a follow‑up process to ensure active and participatory monitoring of the state's progress in meeting its obligations by independent mechanisms, civil society and the UN Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (the UN Committee). Within two years of ratification of the CRPD, each state party is obligated to provide an initial report to this committee, setting out its constitutional, legal and administrative framework for implementation. The UN Committee, which is made up of independent experts nominated by member states for up to two four‑year terms, makes suggestions and general recommendations as part of the review of each report (Articles 34, 35 and 36).30 Subsequent reports track progress made in realizing the rights of persons with disabilities as a result of the implementation of the Convention while responding to the challenges, concerns and other issues highlighted by the UN Committee.

The UN Committee's reports may also be used by the OHCHR or other stakeholders when gathering information for a member state's Universal Periodic Review of its human rights record before the United Nations Human Rights Council.31

Consultation was an important part of the preparation of the CRPD and remains an important part of the implementation process. Under the terms of the Convention, states parties are obligated to engage with persons with disabilities, in particular through their representative organizations, when developing and implementing legislation and policies that will affect them (Article 4.3).32 This responsibility is also extended to the process of reporting to the UN Committee (Article 35).

The Optional Protocol to the CRPD enables the UN Committee to receive complaints about rights violations from individuals or groups of individuals who believe that a state party has violated rights under the Convention. To be admissible, such complaints (referred to as communications) must not be anonymous, all available domestic remedies must have been exhausted and the alleged violations must have occurred after the Optional Protocol came into force in the relevant country.33

The UN Committee considers all admissible complaints and may make comments and recommendations to both the relevant country and the petitioner. In cases of grave or systemic violations of CRPD rights, the Optional Protocol sets out an inquiry procedure. An inquiry may include a visit to the relevant country if that country consents. The UN Committee concludes its inquiry by transmitting its findings and recommendations to the relevant country, which must respond within six months.34

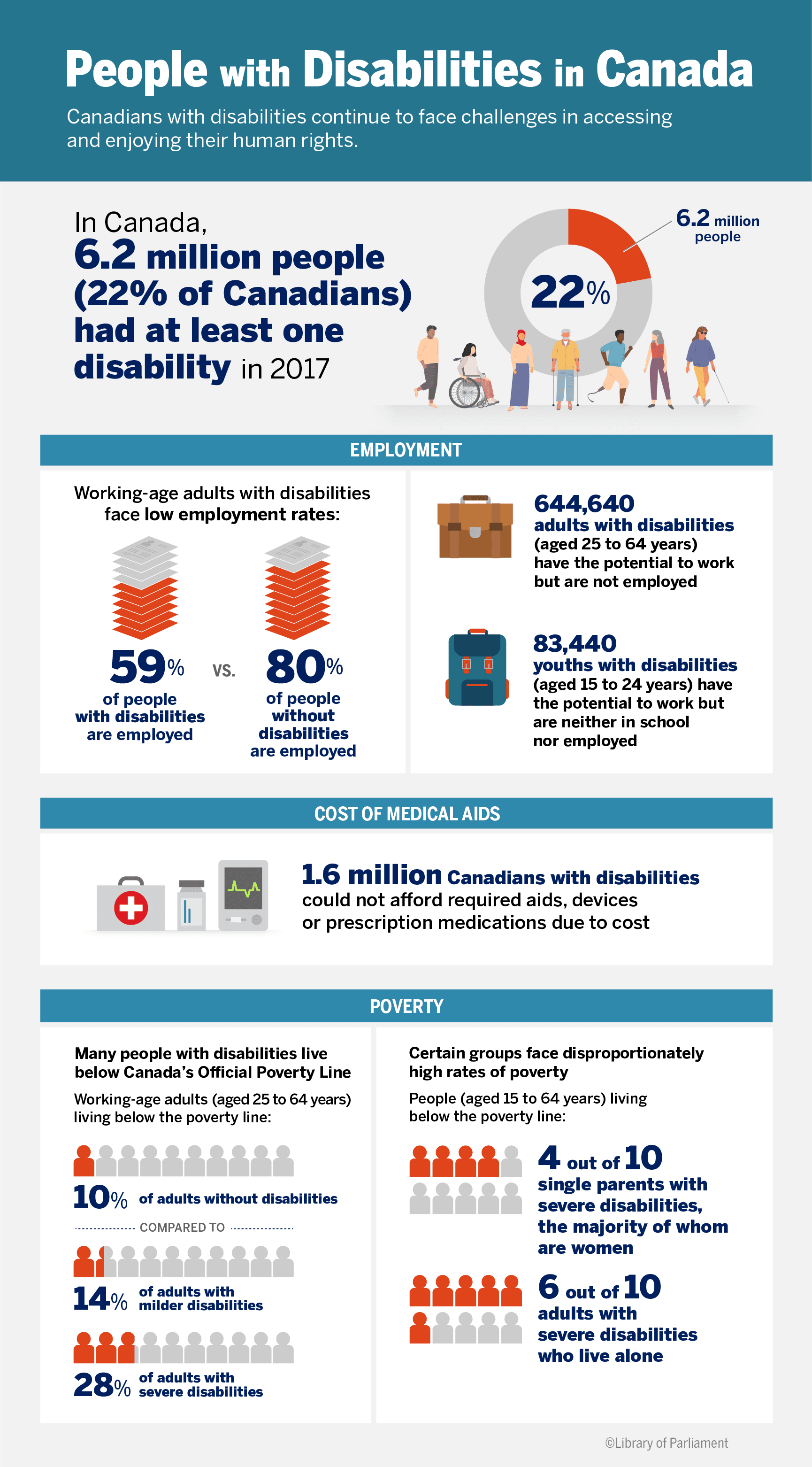

According to Statistics Canada's Canadian Survey on Disability,35 in 2017, about 6.2 million Canadians aged 15 years and over had one or more disabilities that limited them in their daily activities (see Figure 1).36 This represented 22% of the total population aged 15 years and over, excluding those living in institutions and other collective dwellings, on Canadian Armed Forces bases, and on First Nations reserves. The most common disabilities pertained to pain (15%), flexibility (10%), mobility (10%) and mental health (7%).37

Figure 1 – People with Disabilities in Canada

Sources: Statistics Canada, "Canadian Survey on Disability, 2017," The Daily, 28 November 2018; and Stuart Morris et al., "A demographic, employment and income profile of Canadians with disabilities aged 15 years and over, 2017 ![]() (351 KB, 25 pages)," Canadian Survey on Disability, Statistics Canada, 28 November 2018.

(351 KB, 25 pages)," Canadian Survey on Disability, Statistics Canada, 28 November 2018.

Disability rates increase with age. The 2017 survey indicated that 13% of Canadians aged 15 to 24 years had a disability compared to 20% for those aged 25 to 64 years and 38% for those aged 65 years and over. While the prevalence of disability for both men and women rose with age, women (at 24%) were consistently more likely to have a disability than men (at 20%) across all age groups.38 As Canada's population is aging, the incidence of disability can be expected to continue to increase.

Statistics Canada also indicates that the rate of disability is higher among First Nations and Métis peoples in Canada when compared to the non‑Indigenous population. For instance, in 2017, 32% of First Nations people living off reserve and 30% of Métis had one or more disabilities that limited them in their daily activities. Rates of disability among Inuit were lower than the general population, at 19%, in large part because a greater proportion of Inuit are younger than the general population.39 Statistics Canada states that "discrimination, historic oppression and trauma" experienced by Indigenous peoples "are tied to various social and health inequalities," including rates of disability.40

The barriers that prevent persons with disabilities from participating fully in society and ensuring that they have access to appropriate services and programs can be affected and influenced by other factors. Statistics Canada has provided relevant data on these barriers over the years, reporting on such topics as the impact of the COVID‑19 pandemic on Indigenous people with disabilities and on families of children with disabilities; the barriers related to accessibility within federal sector organizations; the experience of intimate partner violence among women with disabilities; and the lower employment rates and annual work hours of persons with disabilities as compared to those of the general population.41

Canada signed the Convention on the day it opened for signature and ratified it on 11 March 2010. Canada did not initially sign the Optional Protocol when it opened for signature in 2007. In December 2016, the Government of Canada announced that it was considering acceding to the Optional Protocol and undertook a public consultation process in early 2017.42 On 3 December 2018, Canada acceded to the Optional Protocol with the support of the provinces and territories.43

Canadian representatives were very involved in the initial development of the CRPD. Representatives from the Government of Canada – in particular, from the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade, Justice Canada, Human Resources and Skills Development Canada (HRSDC) and Canadian Heritage, as they were then known – participated in the drafting and negotiation of the Convention from 2001 onward.44

In their 2011 joint paper, the Council of Canadians with Disabilities and the Canadian Association for Community Living discussed how during both the elaboration and ratification stages, the Government of Canada worked closely with the disability community. The authors noted that Canada's strong contribution to the CRPD allowed certain Canadian values to be enshrined in international human rights law. As examples, Article 5 of the CRPD (equality and non‑discrimination) is very consistent with section 15 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.45 Meanwhile, Article 12 (equal recognition before the law) was

facilitated by the Canadian delegation and secures a progressive approach to legal capacity and, for the first time in international law, recognizes a right to use support to exercise one's legal capacity – a made‑in‑Canada solution; [and] Article 24 (education) secures a right to inclusive education – a concept that Canada, in particular, New Brunswick, is seen as an international leader on.46

Between signing the Convention in 2007 and ratifying it in 2010, the federal, provincial and territorial governments undertook reviews to ensure that the Convention was consistent with existing Canadian laws and policies and that it could be implemented in conformity with the Canadian Constitution. The Office for Disability Issues at HRSDC also led two roundtable public consultations with stakeholders and organizations representing persons with disabilities to obtain their views on what was most important in the implementation process. In addition, the Office for Disability Issues created a temporary public online consultation website.47

Some participants in these consultations indicated that "they were disappointed with the lack of engagement and transparency they have experienced since Canada signed the Convention" and that "there should have been a mechanism to keep civil society and the disability community engaged and informed throughout the ratification process [from 2007 to 2010]."48 They called for the Government of Canada to develop a national implementation plan for the Convention and for it to involve stakeholders and the disability community in its development.49 The Standing Senate Committee on Human Rights, in a 2012 report, also called for the Government of Canada to "ensure that there is open, transparent, and substantive engagement with civil society, representatives from organisations advocating for persons with disabilities, and the Canadian public" with respect to Canada's obligations under the Convention.50

The Convention includes provisions to ensure that a state party's implementation of the treaty is monitored by both the UN treaty body reporting system and independent institutions within the member state. Canada added a reservation and an interpretive declaration pertaining to these provisions when it ratified the treaty. Canada added a reservation51 to Article 12 to permit it to continue to use substitute decision‑making arrangements "in appropriate circumstances and subject to appropriate and effective safeguards."52 It further reserved the right not to subject all such decision‑making arrangements to regular review by an independent authority "where such measures are already subject to review or appeal."53 This position reflects the fact that Canadian provinces and territories have different legislative approaches to supported and substitute decision‑making for people who lack legal capacity.

Canada also made an interpretive declaration54 pertaining to Article 33.2, which is the main provision that sets out the obligation of states parties to create a framework that includes one or more independent mechanisms, such as a national human rights institution, to "promote, protect and monitor" the Convention's implementation. Canada noted that this should be interpreted as accommodating the "situation of federal states where the implementation of the Convention will occur at more than one level of government and through a variety of mechanisms, including existing ones."55

This interpretive declaration reflected Canada's position that Article 33.2 was already implemented at both the federal and provincial/territorial level "through a variety of mechanisms such as courts, human rights commissions and tribunals, public guardians, ombudspersons, and intergovernmental bodies."56 Nevertheless, in 2019, the Government of Canada formally designated the Canadian Human Rights Commission (CHRC) as the body responsible for monitoring the implementation of the Convention.

The Convention requires that states parties submit regular reports regarding their implementation of the Convention, including an initial report that sets out the country's constitutional, legal and administrative framework for implementation. According to Canada's first periodic report, the existing legal framework in Canada at the time of ratification provided the necessary tools to implement the Convention without the need for additional legislation. This framework included the following:

It is important to note that many of the international obligations resulting from Canada's ratification of the CRPD and other international human rights treaties fall within the jurisdiction of the provinces. Many programs for persons with disabilities are run by provinces or territories at the local or municipal level, from providing support services and appropriate health care to ensuring public spaces are accessible or offering appropriate forms of education to meet the needs of persons with disabilities. The federal government has therefore been required to consult and cooperate with provincial and territorial governments prior to ratification and during implementation of the Convention and Optional Protocol.59 Although a full review of provincial responsibilities and efforts in this area is beyond the scope of this HillStudy, Ontario, Manitoba, Nova Scotia, British Columbia, and Newfoundland and Labrador are examples of provinces with legislation that sets minimum standards for accessibility in public spaces and services.60

As discussed in section 5.1 of this HillStudy, Canadians with disabilities continue to face discrimination despite federal, provincial and territorial efforts to implement the CRPD. For instance, in 2020, 54% of all complaints accepted by the CHRC related to disability.61 In a 2019 submission to the UN Committee, a group of Canadian civil society organizations discussed the ongoing discrimination and marginalization faced by people with disabilities in Canada, provided further evidence and stated the following:

[W]e remain concerned that many of the CRPD's general obligations and specific rights are not being implemented or realized in Canada. There is still much that needs to be done to achieve full accessibility, inclusion and true citizenship for persons with disabilities in Canada.

…

Despite … legal protections and social programs, persons with disabilities experience significantly higher rates of poverty, unemployment, exclusion from education and other services, and discrimination compared to persons without disabilities in Canada.62

Furthermore, the group noted that

[m]any communities of persons with disabilities do not have sufficient, sustainable resources to build capacity to effectively participate in local, national and international CRPD implementation and monitoring.63

A separate 2019 submission by a group of community organizations and organizations of people with disabilities describes the intersectional nature of the discrimination encountered by certain groups of people with disabilities:

[P]eople with disabilities in Canada still experience discrimination, and especially if they belong to other groups like being an Indigenous person with a disability, being a woman with a disability, or being an LGBTQI2S+ person with a disability.64

More recently, at the federal level, the Accessible Canada Act,65 which came into force in 2019, has aimed to improve the way that the Government of Canada and organizations within federal jurisdiction address accessibility and interact with Canadians with disabilities. The Act refers in its preamble to Canada's commitments to the CRPD and establishes several new structures and positions:

- the Canadian Accessibility Standards Development Organization … led by a board of directors comprised of a majority of persons with disabilities that will develop accessibility standards in collaboration with the disability community and industry;

- a Chief Accessibility Officer, who will advise the Minister of Accessibility and monitor systemic and emerging accessibility issues; and

- an Accessibility Commissioner, who will spearhead compliance and enforcement activities under the legislation.66

In addition, the federal government has committed to applying Gender‑Based Analysis Plus to policies, programs and legislation. This includes considering the impact of government initiatives on people with disabilities.67

Canada's combined second and third report to the UN Committee is scheduled to be delivered in 2022.68 In advance of this reporting cycle, in November 2019, the UN Committee requested information on a range of issues, including any significant legal reforms in Canada, whether there was a comprehensive national strategy to implement the Convention, and whether mechanisms exist to enable the full and effective participation of persons with disabilities in monitoring and implementing the Convention.69 These and other areas of inquiry reflected submissions from Canadian civil society organizations outlining ongoing issues faced by persons with disabilities in Canada.70

In Canada, the CHRC – the official designated body for monitoring Canada's implementation of the Convention – has highlighted issues that it seeks to have addressed in Canada's next report, including the following:

The CHRC also noted that several disability advocacy organizations support withdrawing Canada's reservation to Article 12, in part because some persons with disabilities are particularly vulnerable to having their legal capacity unfairly questioned, restricted, or removed. The CHRC stated that withdrawing Canada's reservation and implementing Article 12

would require a real shift towards a human rights‑based approach to legal capacity, by replacing substituted decision-making regimes with the appropriate support measures that persons with disabilities may need to exercise their legal capacity.72

The CRPD has prompted an increased focus on laws and policies that affect the rights of persons with disabilities in Canada. While the specific issues facing persons with disabilities will change over time, the Convention is intended to serve as a framework that will continue to advance human rights across different jurisdictions and in changing contexts.

Many states parties will continue to face common challenges, whether in physically transforming public spaces to be more accessible, finding ways to encourage and support the participation of persons with disabilities in society, or developing the resources to ensure that they can make their own decisions concerning their affairs. Ultimately, the Convention will only be as effective as its ability to prompt states parties to build more inclusive societies.

[ Return to text ]anyone who reported being "sometimes," "often" or "always" limited in their daily activities due to a long‑term condition or health problem, as well as anyone who reported being "rarely" limited if they were also unable to do certain tasks or could only do them with a lot of difficulty.

a unilateral statement, however phrased or named, made by a State, when signing, ratifying, accepting, approving or acceding to a treaty, whereby it purports to exclude or to modify the legal effect of certain provisions of the treaty in their application to that State.

See UN, Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties ![]() (157 KB, 31 pages), 23 May 1969, p. 3. [ Return to text ]

(157 KB, 31 pages), 23 May 1969, p. 3. [ Return to text ]

[a] unilateral statement, however phrased or named, made by a State or an international organization, whereby that State or that organization purports to specify or clarify the meaning or scope of a treaty or of certain of its provisions.

See UN, Guide to Practice on Reservations to Treaties ![]() (1.6 MB, 14 pages), 2011, p. 26. [ Return to text ]

(1.6 MB, 14 pages), 2011, p. 26. [ Return to text ]

© Library of Parliament