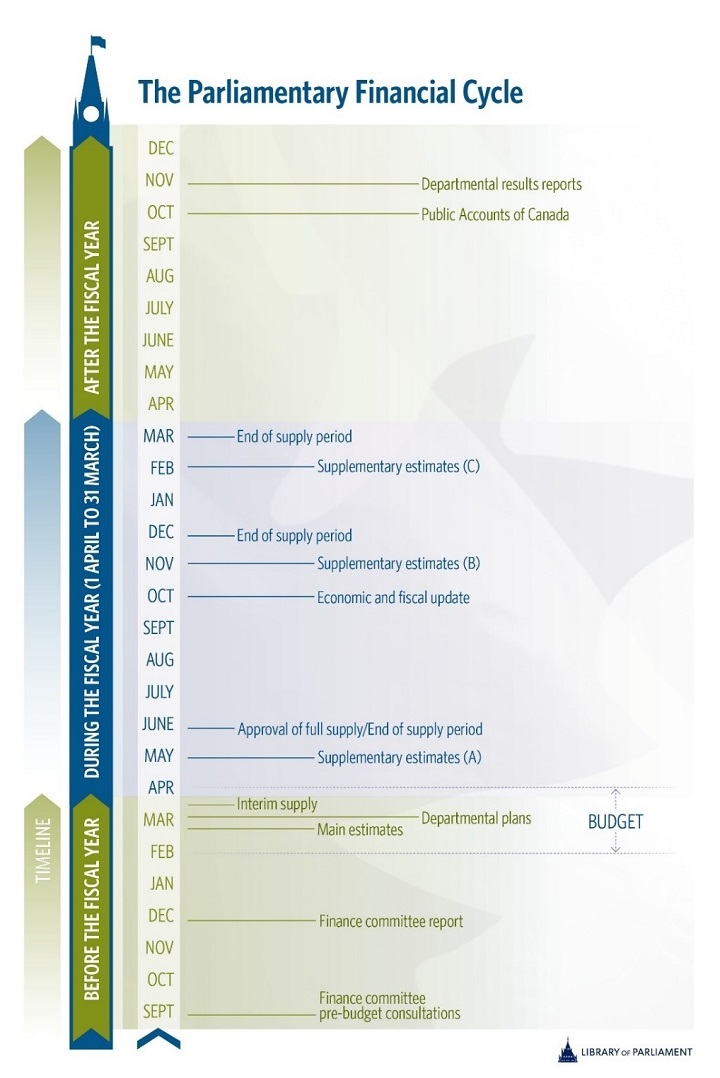

One of Parliament’s fundamental roles is to review and approve the government’s taxation and spending plans. To fulfill this role, parliamentarians follow the parliamentary financial cycle, which consists of a continuous loop of activities that take place throughout the calendar year. Because the federal government’s fiscal year begins on 1 April and ends on 31 March, activities that take place during a single calendar year may relate to different fiscal years. For example, in one calendar year, the budget sets out priorities for the coming fiscal year, while the Public Accounts of Canada outline spending that took place in the previous fiscal year.

Thus, it may be helpful to consider the financial cycle in relation to activities that take place before, during and after the fiscal year. In this way, it can be seen how each element contributes to parliamentary review and approval of government spending for a given fiscal year and takes place over several calendar years.

The financial cycle can also be categorized in terms of the House of Commons’ supply periods, which end on 26 March, 23 June and 10 December. Before the end of each period, the House of Commons votes on whether it agrees with, or concurs in, the estimates and the associated appropriation bills that are before it, which are then sent to the Senate for review and approval.

In the fall prior to the fiscal year, the House of Commons Standing Committee on Finance holds pre-budget consultations with Canadians and makes recommendations to the Minister of Finance for the government’s upcoming budget.

Usually in February or March, the Minister of Finance presents the government’s budget, which outlines the government’s taxation and spending priorities for the coming fiscal year. However, a budget does not authorize the government to change taxation or spend funds, and there is no specific timeline or requirement for the presentation of a budget.

To change taxation, the government introduces ways and means motions that outline the proposed changes. These changes are then enacted by Parliament through the review and approval of legislation, such as budget implementation bills that the government introduces following the budget.

To spend funds, the government must request Parliament’s authorization through the review and approval of appropriation bills. To help Parliament understand and scrutinize its spending plans, the government prepares and presents main and supplementary estimates, which provide the spending plans of each department. In addition, the government receives authorization for statutory expenditures, such as the Canada Health Transfer, through previously adopted legislation. The legislative authority for statutory expenditures is ongoing and does not need annual approval from Parliament.

Before the beginning of the fiscal year, the House of Commons approves interim supply. As full supply is not granted until June, the government needs authorization to spend funds during the first three months of the fiscal year. Thus, interim supply is usually three-twelfths of the amount outlined in the main estimates.

During the fiscal year, once the main estimates have been tabled in the House of Commons, they are referred to the relevant standing committees, which have the opportunity to review, vote and report on them by 31 May. The Standing Senate Committee on National Finance also reviews and prepares reports on the estimates.

In June, the House of Commons approves full supply, which is the amount laid out in the main estimates, less interim supply. Once approved, the appropriation bill is sent to the Senate for consideration and approval.

As the main estimates do not include the government’s complete spending needs for the year, such as unanticipated spending needs or items announced in the budget, the government also presents supplementary estimates to Parliament for review and approval. Although there is no set schedule or limit to the number of supplementary estimates, the government tends to present supplementary estimates in May, November and February, and each set of supplementary estimates receives an alphabetical designation – A, B or C. Supplementary estimates are also referred to committees for review and receive approval through an appropriation bill at the end of the relevant supply period.

In the fall, the Minister of Finance presents an economic and fiscal update, which provides mid-year information on the country’s economic growth and the state of the government’s finances.

Throughout the year, federal departments, agencies and Crown corporations prepare and make public quarterly financial reports, which compare planned with actual expenditures.

Sometime after the end of the fiscal year (usually in October), the government presents its public accounts, which outline the government’s actual spending during the fiscal year. The public accounts also provide a snapshot of the government’s financial position at the end of the fiscal year – its liabilities, assets and net debt. The public accounts are referred to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts.

After the public accounts have been presented, the government tables its Debt Management Report, which presents how it managed the federal debt in the previous fiscal year.

Also in the fall, the government releases departmental results reports for each department or agency. These reports describe achievements relative to the expectations outlined in the corresponding departmental plans presented just before the beginning of the previous fiscal year.

After the completion of the fiscal year, the government’s consolidated financial statements are audited by the Auditor General of Canada.

One of Parliament’s fundamental roles is to review and approve the government’s taxation and spending plans. In fact, the government cannot change taxation rates, impose new taxes or spend public funds without Parliament’s approval.

Despite the importance of financial scrutiny, Parliament’s role in this regard is often not well understood. The goal of this HillStudy is to provide a broad overview of the various components of the Canadian parliamentary financial cycle, and the reporting documents associated with it, to assist parliamentarians in their consideration of the government’s taxation and spending plans.

The paper is organized around the various components of the financial cycle, notably, the budget, the estimates and the public accounts.1

Readers looking for a very brief summary should refer to section 2 (“Overview”). A slightly longer outline can be found in section 4 (“The Financial Cycle”). A glossary of selected terms related to parliamentary procedure is provided in Appendix A.

It should be noted that this HillStudy does not cover all issues related to the parliamentary financial cycle and that other sources provide more in-depth discussions.2

The government sets out its spending and taxation priorities for the coming year, as well as its expectations with respect to revenues, expenses and budgetary balance – surplus or deficit – in its budget, which is presented by the Minister of Finance. The budget is a financial plan, and it does not authorize the government to change taxation or spend funds.

To change taxation, the government introduces ways and means motions that outline the proposed changes, such as increasing tax rates or imposing new taxes. These changes are enacted by Parliament through the review and approval of legislation, such as budget implementation bills.

To spend funds, the government must request Parliament’s authorization through the review and approval of appropriation bills. To help Parliament understand and scrutinize its spending plans, the government prepares and presents main and supplementary estimates, as well as departmental plans.

The government receives authorization for statutory expenditures, such as the Canada Health Transfer to provinces and territories, through previously adopted legislation. The legislative authority for statutory expenditures is ongoing and does not need annual approval from Parliament.

After the completion of the fiscal year, the government explains its achievements in departmental results reports and, in the Public Accounts of Canada, sets out its actual expenditures during the fiscal year and its financial position at the end of the fiscal year. The government’s consolidated financial statements are audited by the Auditor General of Canada (AG).

The origins of the Westminster parliamentary system lie in British feudal society, which gave rise to efforts by the wealthy elite to place constraints on the ability of the monarch to raise funds through taxes and to spend those funds on foreign wars. Over time, Parliament gradually restricted the Crown’s taxation and spending authority. In keeping with this tradition, the Canadian federal government cannot raise taxes or spend funds without first obtaining Parliament’s explicit approval through the adoption of legislation.3

The central role of Parliament in authorizing and providing oversight of government taxation and spending has been codified in legislation, notably the Constitution Act, 1867 and the Financial Administration Act.4 Procedures for the parliamentary financial process are laid out in the Standing Orders of the House of Commons and the Rules of the Senate of Canada.5

Some basic principles of parliamentary control over public funds can be derived from these legislative and procedural requirements, as follows:

These principles ensure that the government retains the prerogative to raise funds through taxation and to plan its spending, while Parliament has the opportunity to scrutinize the government’s taxation and spending plans and to review actual revenues and expenditures. Thus, budget-setting is an executive function, and Parliament’s role is to hold the government to account for how it raises and spends public funds. This scrutiny is undertaken through a series of activities during the financial cycle.

The parliamentary financial cycle may be considered as a continuous loop of activities that take place throughout the calendar year.8 Because the federal government’s fiscal year begins on 1 April and ends on 31 March, activities that take place during a single calendar year may relate to different fiscal years. For example, in one calendar year, the budget sets out priorities for the coming fiscal year, while the public accounts outline spending that took place in the previous fiscal year.

Thus, it may be helpful to consider the financial cycle in relation to activities that take place before, during and after the fiscal year, as set out in Appendix B. In this way, it can be seen how each element contributes to parliamentary review and approval of government spending for a given fiscal year and takes place over several calendar years. Each of the elements noted in sections 4.1 to 4.3 will be discussed in more detail in later sections of this HillStudy.

The financial cycle can also be categorized in terms of the House of Commons’ supply periods, which end on 26 March, 23 June and 10 December.9 Before the end of each period, the House of Commons votes on whether it agrees with, or concurs in, the estimates and the associated appropriation bills that are before it, which are then sent to the Senate for review and approval.

In the fall, the House of Commons Standing Committee on Finance holds pre-budget consultations during which it seeks the views of Canadians on what recommendations it should make to the Minister of Finance for the government’s upcoming budget.

Usually in February or March, the Minister of Finance presents the government’s budget, which outlines the government’s taxation and spending priorities for the coming fiscal year. It should be noted that there is no specific timeline or requirement for the presentation of a budget.10 The government may subsequently introduce budget implementation bills to legislate provisions of the budget, such as changes to taxation.

As an appendix to the budget plan, the government includes its debt management strategy, which describes how it proposes to manage the federal debt in the coming fiscal year.

As the budget is a financial plan and does not provide authorization to spend funds, on or before 1 March, the government tables its main estimates for the coming fiscal year. The main estimates present the government’s spending plans for each federal organization and provide items that will be included in an appropriation bill. It is important to note that the main estimates are prepared in the late fall and thus generally do not include spending items announced in the budget.

On the same day as it tables the main estimates, the government publishes its report on tax expenditures, which are tax measures used in place of direct program spending to promote specific policy objectives.

Later in March, the government tables departmental plans. These plans set out the results that departments intend to achieve with the resources provided to them, and they outline the human and financial resources allocated to each program.

Before the beginning of the fiscal year, the House of Commons approves interim supply. As full supply is not granted until June, the government needs authorization to spend funds during the first three months of the fiscal year. Thus, interim supply is usually three-twelfths of the amount outlined in the main estimates.11

Once the main estimates have been tabled in the House of Commons, they are referred to the relevant standing committees, which have the opportunity to review, vote and report on them by 31 May.12 The Standing Senate Committee on National Finance also reviews and prepares reports on the estimates.

In June, the House of Commons approves full supply, which is the amount laid out in the main estimates, less interim supply. Once approved, the appropriation bill is sent to the Senate for consideration and approval.

As the main estimates do not include the government’s complete spending needs for the fiscal year, such as unanticipated spending needs or items announced in the budget, the government also presents supplementary estimates to Parliament for review and approval. Although there is no set schedule or limit to the number of supplementary estimates, the government tends to present supplementary estimates in May, November and February, and each set of supplementary estimates receives an alphabetical designation – A, B or C. Supplementary estimates are also referred to committees for review and receive approval through an appropriation bill at the end of the relevant supply period.

In the fall, the Minister of Finance presents an economic and fiscal update, which provides mid-year information on the country’s economic growth and the state of the government’s finances.

Throughout the year, federal departments, agencies and Crown corporations prepare and make public quarterly financial reports, which compare planned with actual expenditures.13

Sometime after the end of the fiscal year (usually in October), the government presents its public accounts, which outline the government’s actual spending during the fiscal year. The public accounts also provide a snapshot of the government’s financial position at the end of the fiscal year – its liabilities, assets and net debt. The public accounts are referred to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts.

After the public accounts have been presented, the government tables its Debt Management Report, which presents how it managed the federal debt in the previous fiscal year.

Also in the fall, the government releases departmental results reports for each department and agency. These reports describe achievements relative to the expectations outlined in the corresponding departmental plans presented just before the beginning of the previous fiscal year.

The budget, which sets out the government’s overall taxation and spending priorities, is a key component of the financial cycle and is summarized in the budget speech. Other aspects of the preparation and implementation of the budget include pre budget consultations, fiscal updates, ways and means motions, budget implementation bills, borrowing authority and debt management, and tax expenditures, as well as the role played by the Parliamentary Budget Officer in helping parliamentarians better understand the government’s budgeting practices.

Since 1994, the House of Commons Standing Committee on Finance has conducted pre-budget consultations.14 The committee often structures its consultations around a number of topics related to the government’s budgetary policy. During these consultations, the committee solicits written submissions from individual Canadians and interested organizations during the summer, holds public hearings (often across the country during the fall) and presents a report to the House of Commons in December.

The committee’s report, which reflects the opinion of a majority of its members, summarizes the submissions and testimony it received and makes recommendations to the government for the upcoming budget. Other committee members may request the right to append supplementary or dissenting opinions to the report.

Although the government is not obligated to act on the committee’s recommendations, the pre-budget consultations provide an opportunity for parliamentary input into the budget planning process, and for public discussion and debate regarding the government’s spending and taxation priorities.15

The Minister of Finance also holds pre-budget consultations and solicits written submissions from Canadians.

Next to the Speech from the Throne, the budget speech is one of the government’s most important policy statements. It sets out the government’s outlook for the economy and employment, explains its expectations for the budgetary balance, and announces new spending initiatives, increases or decreases to spending, and changes to taxation.

The Minister of Finance develops the budget with the support of the Department of Finance Canada, which analyzes the fiscal implications of budget proposals in close consultation with the prime minister and the Privy Council Office.16

After giving notice, the Minister of Finance usually delivers the budget speech to the House of Commons late in the afternoon, after the financial markets have closed. The speech is accompanied by a more detailed budget plan, which is made available several hours in advance to parliamentarians, journalists and other interested parties in a closed-door information “lock-up.” As the budget may have an impact on financial markets, its contents remain confidential until the minister presents the budget to the House of Commons.

Before delivering the budget speech, the Minister of Finance will move a ways and means motion that the House of Commons approve in general the budgetary policy of the government. After up to four days of debate and the opportunity for the opposition parties to present an amendment and a sub-amendment, the House of Commons will vote on the minister’s motion.17 Adoption of this motion does not authorize the government to change taxation or to spend funds, which must come through the ways and means and supply processes. Rather, it indicates general approval of the government’s financial plan. The failure of this motion to pass would likely indicate a loss of confidence in the government by the House of Commons.

The budget plan is often an extensive document that begins with a detailed discussion of the country’s recent economic performance. Using an average of private sector economic forecasts as a basis for fiscal planning, and including an adjustment for risks to the economy, the Department of Finance Canada provides projections for the government’s revenues, expenses and budgetary balance.18 This overall fiscal framework provides the context for taxation and spending announcements.

Within the budget plan, taxation and spending priorities are organized by policy themes relevant to the government of the day. Proposed changes to taxation are accompanied by a projection of their budgetary impact and by notices of ways and means motions, which are required to put in place changes to taxation. Spending announcements usually have a profile, that is, the years over which the spending will take place and the corresponding amounts.19 Lastly, the budget plan may include policy announcements that do not have specific budgetary implications, such as a commitment to undertake copyright reform.

The budget documents are usually tabled in the Senate. The Senate may debate the merits and weaknesses of the budget but does not vote on the budget speech.

In the fall, the Minister of Finance provides an economic and fiscal update, which includes up-to-date information on the country’s economic developments and prospects, the government’s fiscal situation, including its outlook for revenues and program expenses, and risks to fiscal projections. The update may also include a long-term economic and fiscal projection. On several occasions, the update has announced proposed changes to taxation, leading some observers to call it a “mini-budget.”

In some years, the update has been presented to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Finance, while in other years it has been presented outside Parliament. The information it provides may contribute to the committee’s pre-budget consultations and report.

Through the Fiscal Monitor, the Department of Finance Canada releases monthly updates on the government’s fiscal performance to that point in the fiscal year, including an estimate of revenues, expenses and the budgetary balance.20

Before the government can introduce a bill to impose a new tax, increase the rate of an existing tax, continue an expiring tax or extend the coverage of a tax, it must first introduce, and have the House of Commons adopt, a ways and means motion.21 The requirement for a ways and means motion means that tax increases are the prerogative of the government, as only ministers may introduce them. However, legislative proposals to reduce the level of taxation do not need to be preceded by a ways and means motion before being introduced.

Ways and means motions establish limits, such as tax rates and their applicability, on the scope of the associated tax legislation. The motions may be general or very specific, as in the form of draft legislation. The corresponding bill must be based on the motion but does not need to be identical to it. Once the motion is adopted, a bill may be introduced with the proposed tax measures. It should be noted that, unlike appropriation bills or unless otherwise indicated, changes to taxation authorized by legislation do not need to be renewed.

As it may take some time before legislation implementing tax measures is passed, the government’s long-standing practice is to implement, provisionally, some tax measures as of the date of the notice of a ways and means motion, or, in some cases, the date of the Minister of Finance’s announcement of the proposed changes. The rationale for provisional implementation is that if some tax measures were not immediately put in place, their effectiveness could be diminished, it would be difficult for the Minister of Finance to forecast expected revenues, and certain taxpayers could gain unintended advantages.22 The result is that taxes may be collected before the proposed changes have the force of law.

To implement various measures associated with the budget, the government introduces budget implementation bills. As with other legislation, these bills are given three readings in the House of Commons and the Senate and are referred for review by committee – usually the House of Commons Standing Committee on Finance and the Standing Senate Committee on National Finance.23

There are often two budget implementation bills associated with a given budget, one in the spring and one in the fall. Changes to taxation announced in the budget are usually included in budget implementation bills rather than in separate tax bills.

The size of budget implementation bills and the inclusion of items not related to the budget have been the subject of discussion.24

The government exercises its borrowing authority when its revenues do not cover the expenditures that are authorized by Parliament through ongoing statutes and annual appropriations.

The Budget Implementation Act, 2007 made changes to the Financial Administration Act to allow the Governor in Council to authorize the Minister of Finance to borrow money, which previously was authorized through borrowing authority bills passed by Parliament. That is, instead of parliamentary approvals, borrowing limits required only the approval from the Governor in Council through an order in council.25

Subsequently, the Budget Implementation Act, 2016, No. 1 and the Budget Implementation Act, 2017, No. 1 amended the Financial Administration Act to restore the requirement that the Minister of Finance seek parliamentary approval to borrow on behalf of the government.26 To fulfill the requirement for parliamentary approval, the Borrowing Authority Act was adopted by Parliament in November 2017, which sets the maximum amount of outstanding Government of Canada and agent enterprise Crown corporation market debt at $1,168 billion. In addition, it also requires the government to report to Parliament on the total amount of money borrowed within three years of the Act coming into force.

As part of the changes made to the Financial Administration Act through the Budget Implementation Act, 2007, the government must table in Parliament a debt management report on how it managed the debt in the previous fiscal year and a debt management strategy describing how it proposes to manage the debt in the coming fiscal year.27 The debt management strategy is included as an annex to the budget plan. These documents focus on the portion of the debt that is borrowed in financial markets and the investment of cash balances in liquid assets until they are needed for operations.28

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, in March 2020, Parliament amended the Financial Administration Act through the COVID-19 Emergency Response Act to do the following:

Through the COVID-19 Emergency Response Act, Parliament also amended the Borrowing Authority Act to exclude the borrowings required under any Act of Parliament or for extraordinary circumstances from the borrowing limit set out in the Act.30

In May 2021, Parliament amended the Borrowing Authority Act again to increase the borrowing limit to $1,831 billion as part of the Economic Statement Implementation Act, 2020.31

Through specific tax measures, such as low rates, exemptions, deductions, deferrals and credits, the tax system can be used to achieve economic and social public policy objectives. As these measures result in lower tax revenues and may be used in place of spending programs, they are called tax expenditures. The federal government forgoes tens of billions of dollars in revenue each year as a result of tax expenditures.32 Examples include the Charitable Donation Tax Credit and the Tuition Tax Credit.

The Department of Finance Canada prepares an annual report on tax expenditures that provides estimates for the amount of revenue forgone for each tax expenditure, and evaluations and analytical papers examining different specific tax expenditures.33

In 2015, the AG noted that tax expenditures, unlike direct program spending, were not systematically evaluated and that the information reported on them did not adequately support parliamentary oversight.34

In 2006, the position and office of the Parliamentary Budget Officer (PBO) was created to make the government’s fiscal forecasting and budget planning process more transparent, credible and accountable to Parliament.35 In 2017, through the Budget Implementation Act, 2017, No. 1, the PBO was made a distinct office and given an expanded mandate.36

As a result of changes made in 2017, the PBO now has two distinct mandates. When Parliament is not dissolved, the PBO provides independent economic and financial analysis to the Senate and House of Commons, analyzes the estimates of the government and, if requested, estimates the financial cost of any proposal over which Parliament has jurisdiction. However, during the 120-day period before a fixed general election or when Parliament is dissolved for a general election, the PBO provides political parties, at their request, with estimates of the financial cost of election campaign proposals they are considering making.37

While Parliament is not dissolved, to help parliamentarians analyze the government’s budgeting practices and fiscal situation, the PBO produces economic and fiscal outlook analyses, economic and fiscal monitors, labour market assessment reports, analyses of the main and supplementary estimates, and fiscal sustainability reports, as well as stand-alone reports on matters related to the nation’s economy or finances.38

The 2019 general election was the first election in which the PBO was able to provide financial cost estimates of election campaign proposals that political parties and independent members were considering.39

One of the PBO’s difficulties in fulfilling its mandate has been obtaining access to all requested data and information from the government.40

Approval of the Minister of Finance’s budget does not authorize the government to spend funds. Instead, Parliament authorizes government spending through the estimates and the associated appropriation bills. This process is often called the business of supply.

Before 1968, the estimates were considered by committees of the whole House of Commons. Each estimate was considered as a separate resolution or motion, amendments were permitted and no time limits were placed on debate. The procedures reflected the long-standing tradition that grievances should be considered before granting supply to the Crown.

The consequence of these procedures was that the opposition, in an effort to obtain concessions from the government, would often delay the adoption of motions granting supply until late in the session. However, the opposition’s tactics meant that a considerable amount of the House of Commons’ business was devoted to supply matters, even though it engaged in limited substantive debate on the estimates.

With the intention of providing greater and more efficient scrutiny of the estimates, starting in 1968, all estimates were referred to appropriate standing committees for consideration. To ensure that supply was considered and voted upon in a timely manner, the House of Commons schedule was divided into three supply periods, with votes on supply taking place at the end of each period. In lieu of being able to delay the adoption of motions granting supply, the opposition was granted a number of days during which it could control the business of the House of Commons and initiate debates and votes on items it felt needed attention and discussion.

To provide the government with a clear timeline for the consideration of supply, the House of Commons schedule is divided into three supply periods, ending respectively on 26 March, 23 June and 10 December. The opposition is provided with 22 “allotted days,” or “supply days,” on which their motions take precedence over government supply motions.

The allotted days are scheduled by the government: seven take place in the supply period ending 26 March, eight in the period ending 23 June and seven in the period ending 10 December. On supply days, the opposition may present motions on any matter falling within the jurisdiction of Parliament. Thus, although the motions are formally part of the supply process, they are not confined to issues related to supply.

On the last allotted day for supply in each period, the House of Commons votes on motions to concur in (i.e., express its agreement with) the estimates that have been presented during that supply period. Once the House of Commons votes to concur in the estimates, the government introduces an appropriation bill to give legislative effect to the estimates.

In unique circumstances – for example, when the parliamentary calendar is shortened because of an election – the timing of the supply periods and the number of allotted supply days may be adjusted.

On or before 1 March, that is, a month before the beginning of the fiscal year, the government presents its expenditure plan (part I of the estimates) and the main estimates (part II of the estimates), which are combined into one document.41

The government expense plan provides a general overview of amounts included in the main estimates, including the overall composition of expenditures and a comparison of the main estimates with expenditures made in previous years.

The main estimates present the government’s appropriation needs for each federal organization. The main estimates are divided into votes for each organization, which form an annex to the associated appropriation bill.42

The “voted” expenditures are approved annually by Parliament, and the authorization they provide to spend funds expires at the end of the fiscal year. Statutory expenditures, on the other hand, have ongoing authorization and are included in the main estimates for information purposes only.

For each organization, the main estimates include highlights of major year-to-year changes, expenditures by strategic outcome and program, and a list of transfer payment programs. In general, the spending information provided in the main estimates is highly aggregated and is not broken down into more specific categories. Thus, the main estimates are best read in conjunction with departmental plans, which contain more detailed information.

The main estimates are prepared in the fall by the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat in conjunction with federal organizations through an analysis of the funding levels needed to maintain existing programs and services for each organization, and they incorporate adjustments to reflect increases or decreases to program funding levels approved by the Treasury Board.43 This process is called the Annual Reference Level Update.44

The main estimates do not present the entirety of planned federal spending for the coming fiscal year since subsequent spending announcements, such as those included in the budget, or spending needs identified during the year will be included in supplementary estimates.

It should be noted that the government’s overall spending projections outlined in the budget and the main estimates are not readily comparable; this is due, in part, to the fact that they are prepared using different accounting methods.45

After they are tabled, the main estimates are referred to the appropriate standing committee for review.

Each federal organization included in the main estimates has one or more votes. The numbers assigned to a vote, for example, Vote 1 and Vote 5, are arbitrary and are merely used to distinguish votes.

Votes specify limits to expenditures that cannot be exceeded and thereby act as Parliament’s control on government spending. To spend more than the amount specified in a vote, Parliament must approve additional amounts in supplementary estimates. Thus, federal organizations must spend less than the amount allocated in a vote. They may carry forward into the next fiscal year a portion of their unspent funds through the Treasury Board’s carry-forward votes, which are discussed below. Funds that are not spent or are not carried forward lapse at the end of the fiscal year.46 The amount of funding that lapsed is identified in the Public Accounts of Canada.

Transfers between votes, either within an organization or between organizations, also require the approval of Parliament. Organizations do not need Parliament’s approval to transfer funds within a vote from one program to another, nor must they inform Parliament of such transfers. Although the main estimates may include details about program spending, this is for information purposes only. Thus, Parliament may or may not be informed of reductions or reallocations in program spending.

Vote wording indicates the purposes of the funding, and Parliament must approve any changes to the wording, for example, to provide authority for an organization to re spend revenues received for providing services.

There are several common types of votes:

The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat manages several central votes that apply across federal organizations, including a government contingencies vote and operating and capital budget carry-forward votes.

The contingencies vote is used to provide immediate funding to organizations that cannot wait until approval of the next supplementary estimates for increased funding.

To reduce year-end spending, the carry forward votes permit organizations to carry forward a portion – usually up to 5% of the total amount appropriated for operating expenditures and 20% for capital expenditures – of their unspent funds from the previous fiscal year into the current fiscal year. Other central votes include government-wide initiatives, public service insurance payments and paylist requirements.

Statutory expenditures are based on continuing legislative authority to undertake expenditures and do not require regular approval by Parliament.

Examples of statutory expenditures include major transfers to the provinces and territories, such as the Canada Health Transfer and equalization payments, and transfers to individuals, such as Old Age Security payments.

Parliament authorizes statutory expenditures through previously adopted legislation, such as, in the examples noted above, the Federal–Provincial Fiscal Arrangements Act and the Old Age Security Act. The amounts spent under statutory expenditures are determined by the provisions of the relevant statute and by independent factors such as the growth of the population and provincial economies. Changing the factors that determine the amounts to be spent would require changes to the authorizing legislation.

To provide an overall picture of expenditures, the main estimates include summary information of statutory expenditures for each federal organization. Statutory expenditures account for a significant portion of the expenditures for Employment and Social Development Canada and the Department of Finance Canada. For the federal government as a whole, statutory expenditures account for approximately two-thirds of federal expenditures, and voted expenditures account for approximately one-third of expenditures.

Forecasted expenditures for each statutory item are included in a separate document called Statutory Forecasts.48 The forecasts are provided for information purposes, rather than to indicate an amount to be authorized by Parliament.

As statutory programs do not receive regular parliamentary scrutiny, in 2012, the House of Commons Standing Committee on Government Operations and Estimates recommended that standing committees review them on a cyclical basis.49

The main estimates do not contain all of the government’s spending needs for the year. To obtain approval for additional funding, the government submits supplementary estimates to Parliament. There is no limit to the number of supplementary estimates that may be presented, but generally the government submits three supplementary estimates during the fiscal year – in the spring, fall and winter – and each supplementary estimate is designated by a letter: supplementary estimates A, supplementary estimates B, and so on.

Like the main estimates, the supplementary estimates are divided into votes, are referred to standing committees for review and provide information to support the consideration of an appropriation bill. The appropriation bill associated with supplementary estimates is presented at the end of the supply period during which the supplementary estimates were presented.

Unlike the main estimates, the supplementary estimates contain brief statements outlining the requirements for additional expenditure authorities. However, the extent to which the descriptions provided in supplementary estimates clearly explain spending requirements varies.50

The supplementary estimates include spending items not sufficiently developed for inclusion in the main estimates, such as budget announcements, unanticipated funding requirements, the transfer of funds between votes – either within or between organizations – funds for temporary programs and various other funding needs. Details on vote transfers, and updated information on forecasted statutory expenditures and the use of central votes, such as the operating budget carry forward vote, are included in separate documents.51

Supplementary estimates provide information on “authorities to date” that includes amounts previously adopted in main and supplementary estimates, allocations from central votes and funds related to the transfer of responsibilities between federal organizations.

Supplementary estimates include “one-dollar items.” These items are used because no additional funding is required but an amount must be presented for parliamentary approval of the item. One-dollar items may be used to transfer funds between votes, to write off debts, to adjust loan guarantees, to authorize grants, to amend vote wording or to amend previous appropriation Acts.

Supplementary estimates also contain a list of horizontal items – initiatives that involve more than one organization, such as funding related to the remediation of contaminated sites. A brief description of horizontal items, as well as how much each organization will spend on each initiative, is provided.

To provide additional context to the spending information included in the main estimates, federal departments and agencies prepare departmental plans and departmental results reports. Together, these reports constitute part III of the estimates.

Departmental plans and departmental results reports were previously called “reports on plans and priorities” and “departmental performance reports,” respectively. They were renamed during a 2016 reform of the reporting process in response to concerns about the low quality of information provided in these reports.52

Departmental plans provide a detailed overview of priorities, strategic outcomes, program activities, and planned and expected results over a three-year period. They also provide details on human resource requirements, major capital projects, grants and contributions, and net program costs.

Departmental results reports are prepared after the fiscal year is completed and provide information about the resources used during the year and a comparison of results achieved with the projections outlined in the corresponding departmental plans.

Moreover, as part of the reform, the government has developed the searchable GC InfoBase, which provides detailed financial and human resources information.

The content and structure of these departmental reports have been changed so that “parliamentarians are provided with better information on planned spending, expected outcomes and actual results.”53 However, the usefulness of these reports may still be limited by certain shortcomings. For instance, a PBO report pointed out that the majority of 2019–2020 departmental plans did not provide any details on measures contained in the 2019 federal budget.54

In the House of Commons, main and supplementary estimates votes are referred to standing committees according to their mandates. In the Senate, all estimates are reviewed by the Standing Senate Committee on National Finance.

As part of the 1968 amendments to the estimates process, House of Commons standing committees have a specific deadline by which they must review and report estimates votes back to the House of Commons. If they do not report the votes back by the deadline, they are deemed to have reported. For the main estimates, the deadline is 31 May, and for the supplementary estimates, the deadline is three sitting days before the final sitting or the last allotted day in the relevant supply period. However, as the last allotted day is not set in advance, it can be difficult to know the date by which the supplementary estimates votes must be reported.55

House of Commons standing committees may approve, reduce or “negative” – that is, reject – the estimates votes referred to them.56 They cannot increase the amount of a vote or change the way funds are to be used as these are prerogatives of the government and require a royal recommendation. Similarly, they cannot transfer funds between votes because this would have the effect of increasing a vote. Standing committees also cannot make substantive reports on estimates votes.57 They may, however, make substantive reports on organizational plans and priorities or performance.58

Some observers have noted that House of Commons standing committees do not devote many meetings to considering the estimates; this criticism has led to proposals for further reform.59

Unlike House of Commons standing committees, the Standing Senate Committee on National Finance has no procedural timeline for its review of the estimates; it does not vote on the estimates, and its reports tend to be substantive summaries of its meetings. Also, many of its meetings are devoted to considering the main and supplementary estimates.

In addition to standing committee review, the Leader of the Opposition may select, in consultation with the leaders of the other opposition parties, the main estimates of two departments or agencies for consideration by the Committee of the Whole in the House of Commons for up to four hours for each organization.

On the last allotted day in the supply period, the government will move a motion of concurrence in the House of Commons on the estimates that are before it. Concurrence in this motion is an order of the House of Commons to bring in an appropriation bill.

Appropriation bills, whose titles normally begin “An Act for granting to Her Majesty certain sums of money for the federal public administration for the financial year ending,” are based on the estimates that have been considered by the House of Commons, specifically the estimates votes that are included in the main and supplementary estimates. The bills are for interim supply, full supply or supplementary estimates.

Appropriation bills proceed through three “readings” and consideration by a Committee of the Whole. The readings take place very quickly, on the presumption that the estimates on which the bill is based have already been closely examined by standing committees.

After it is passed by the House of Commons, the appropriation bill is forwarded to the Senate for consideration and adoption.60 The Senate does not vote on the estimates, and appropriation bills are not customarily sent to committee for review. However, the Standing Senate Committee on National Finance usually conducts an in-depth study of the expenditures set out in the estimates, and the Senate may consider the committee’s reports on the estimates.

Once adopted and given Royal Assent by the Governor General, the appropriation Act authorizes funding to be released from the Consolidated Revenue Fund for the amounts and purposes outlined in the Act.

It should be noted that some federal organizations are authorized to re-spend non-tax revenues they receive for services provided.61 In these instances, the estimates votes are “netted,” or reduced, against re-spendable revenues; thus, the planned expenditures of these organizations include both their estimates votes and their re spendable revenues. Some Crown corporations are self-financing; that is, they receive sufficient revenues to cover expenditures and thus do not require an estimates appropriation.62

Should Parliament fail to adopt an appropriation bill, the government would not be authorized to spend funds. However, the loss of a vote on concurrence in the estimates or on an appropriation bill would signify a loss of confidence in the government by the House of Commons, leading to the formation of a new government or to the dissolution of Parliament for a general election.63 Presumably, a new government would be able to pass an appropriation bill; during a general election, government spending may be authorized by special warrants.

When Parliament is dissolved for a federal general election, it cannot meet to pass bills that authorize government spending. Thus, if necessary, the government may obtain authority for expenditures during an election, and shortly thereafter, through special warrants, which are signed by the Governor General and are thus called the Governor General’s special warrants.64

Three conditions must be satisfied before a special warrant can be issued:

Special warrants may continue to be issued until 60 days after the date fixed for the return of the writs after a federal general election. Notices of special warrants must be published in the Canada Gazette within 30 days of being issued, and the President of the Treasury Board must present to Parliament within 15 days of its return a statement of special warrants issued. The amounts authorized by special warrants are deemed to be included in the next appropriation bill passed by Parliament.

Although major changes to the House of Commons supply process were undertaken in 1968, modifications to the process continue to be made. For example, in 2001, the Standing Orders of the House of Commons were amended to allow the Leader of the Opposition to select the estimates of two departments or agencies for debate in the Committee of the Whole. Moreover, in 2002, the House of Commons Standing Committee on Government Operations and Estimates was created with a mandate, among other matters, to review and report on the process for considering the estimates and supply.

In October 2016, the government released a discussion paper on reforming the estimates process entitled Empowering parliamentarians through better information.66 The paper proposed four pillars:

During the 42nd Parliament, the House of Commons adopted a motion to amend the Standing Orders on 20 June 2017.67 The changes included the following:

Prior to these changes, the budget would announce spending, organizations would seek Treasury Board approval for detailed spending plans, and Parliament would authorize the spending in subsequent supplementary estimates. The amended Standing Orders allowed for a new alignment of the budget and the main estimates during the life of the 42nd Parliament.

Specifically, the 2018 federal budget included an annex that outlined the budget’s spending measures by federal organization, and this spending was included in the 2018–2019 main estimates through a new Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat Central Vote 40 – Budget Implementation.

In most cases, Parliament directly authorizes spending by federal organizations through their estimates votes. With this new central vote, Parliament authorized the Treasury Board to provide the funding to organizations once Parliament had reviewed their detailed spending plans.

As the new vote came under the authority of the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, it was referred in its entirety to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Government Operations and Estimates for review, rather than each spending measure being referred to the relevant standing committees.

In the 2019–2020 main estimates, rather than being included in a centrally managed budget implementation vote (Central Vote 40), each voted budgetary measure in the 2019 federal budget had a separate vote in the department identified in order to “provide parliamentary committees with greater opportunity to examine individual Budget 2019 measures, as well as greater control over the funding related to budget announcements.”68

The temporary changes introduced in 2017 expired at the dissolution of the 42nd Parliament in 2019 and were not reintroduced in the 43rd Parliament.

In addition to authorizing government spending, Parliament has the opportunity to review and hold the government to account for how it has spent and managed public funds.

After the end of the fiscal year, the government prepares its public accounts, which present its financial position at the end of the year and its actual spending during the year, as compared with its projected budget and authorities granted by Parliament. The AG audits the government’s consolidated financial statements and presents performance audits to Parliament for review.

The Public Accounts of Canada are prepared on a full accrual accounting basis69 and are divided into three volumes:

Detailed information relating to several sections of Volume III is also made available as follows:

To provide Parliament with assurance on the reliability of the federal government’s consolidated financial statements, the AG gives an opinion on whether the financial statements

If the misstatements identified by the AG are such that a person relying on the financial statements could be erroneously influenced in their decisions, then the AG includes a reservation, or qualification, in the AG’s audit opinion and describes the nature and extent of the concerns.71

In addition to the audit of the federal government’s consolidated financial statements, the AG also conducts approximately 95 financial audits of federal and territorial organizations every year.

The AG presents to Parliament approximately 15 to 20 performance audits each year.72 Performance audits provide an assessment of how well the government is managing its activities, responsibilities and resources. They examine whether government programs are managed with due regard to economy and efficiency and whether the government has the means to measure and report on program effectiveness. The AG’s performance audits make recommendations to improve program management. The AG has the discretion to determine which areas will be examined in performance audits.

The Public Accounts of Canada, including the AG’s opinion, are referred to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, as are all reports of the AG.

Other standing committees may review the AG’s performance audits that lie within their mandates.

The Standing Senate Committee on National Finance may also review the AG’s performance audits.

The processes, procedures and documents outlined in this HillStudy enable Parliament to fulfill its role in scrutinizing the government’s taxation and spending plans and in holding the government to account for how it raises and spends public funds.

Moreover, recent reform attempts have been made to streamline the Parliamentary scrutiny processes. Although the 2017 changes to the Standing Orders of the House of Commons relating to the estimates process expired at the end of the 42nd Parliament, lessons learned from this attempt may aid parliamentarians in considering future reforms to the estimates process. In addition, parliamentarians may also wish to take into account the following issues:

| Allotted day | A day reserved for the discussion of the business of supply, the actual topic of debate being chosen by a member in opposition. |

| Appropriation | A sum of money allocated by Parliament for a specific purpose outlined in the government’s spending estimates. |

| Business of supply | The process by which the government submits its projected annual expenditures for parliamentary approval. It includes consideration of the main and supplementary estimates, interim supply, motions to restore or reinstate items in the estimates, appropriation bills, and motions debated on allotted days. |

| Business of ways and means | The process by which the government obtains the necessary resources to meet its expenses. It has two essential elements: the presentation of the budget and the motions which lead to the introduction of tax bills. |

| Committee of the Whole (House) | All of the members of the House sitting in the Chamber as a committee. Presided over by a chair rather than by the Speaker, it studies appropriation bills and any other matters referred to it by the House. |

| Consolidated Revenue Fund | The government account which is drawn upon whenever an appropriation is approved by Parliament and replenished through the collection of taxes, tariffs and excises. |

| Fiscal year | The 12-month period, from 1 April to 31 March, used by the government for budgetary and accounting purposes. |

| Royal recommendation | A message from the Governor General, required for any vote, resolution, address or bill for the appropriation of public revenue. Only a minister can obtain such a recommendation. |

| Statutory expenditures | Expenditures authorized by Parliament outside the annual supply process. Acts authorizing statutory expenditures give the government the authority to withdraw funds from the Consolidated Revenue Fund for one or more years without the annual approval of Parliament. |

| Supply periods | One of three periods into which the parliamentary calendar is divided for the purpose of the consideration of the business of supply. Opposition allotted days are divided among the supply periods, which end, respectively, on 10 December, 26 March and 23 June. |

| Vote | An individual item of the estimates indicating the amount of money required by the government for a particular program or function. |

Source: Table prepared by the Library of Parliament using information obtained from House of Commons, Glossary of Parliamentary Procedure.

Figure B.1 – The Parliamentary Financial Cycle

Source: Figure prepared by Library of Parliament.

Figure B.2 – The Parliamentary Financial Cycle, 2018–2019 and 2019–2020

Source: Figure prepared by Library of Parliament.

© Library of Parliament