The federal government has authority over matters related to health and health care derived mainly from its criminal law power for issues related to public health and safety, and from its spending power through which it makes transfers to the provinces and territories, including health transfers. The federal government contributes to the provinces' and territories' public health spending primarily through the Canada Health Transfer (CHT). It can also fund targeted health care directly. It negotiates with each province the amounts to be transferred to them and the use of the funds. In 2017, it granted funding over 10 years to the provinces for home care and mental health initiatives.

Approximately 70% of health spending in Canada comes from public funding, and this percentage has remained stable in the last 20 years. The balance of funding comes from private sources, mainly out-of-pocket spending and private insurance. The proportion contributed to public funding by the Canada Health Transfer has risen from 21% in 2012 to 23.5% in 2019. In late 2020, the federal and provincial governments signed the Safe Restart Agreement which provides funding to the provinces to help them deal with future waves of COVID‑19 and restart their economies.

Canada does not have a single health care system; rather, each of its provinces and territories1 provides publicly funded health care. In addition, some health services are not covered by provincial public insurance programs. Accordingly, the total health expenditure in Canada comprises public funds from provincial and federal sources, as well as private funds from private insurance and out‑of‑pocket spending.

This paper provides an overview of the legislative basis for Canada's publicly funded health care systems. It also includes a description of recent and projected levels of federal funding for health and health care, a discussion about public versus private health spending in Canada and directed federal funding that considers the impact of COVID‑19 on health costs.

The division of powers between federal and provincial governments with respect to health is not specifically addressed in the Constitution Act, 1867,2 except as it concerns the assignment of federal responsibility for quarantine, the establishment and maintenance of marine hospitals, and the assignment of provincial responsibility for operating most other hospitals. Rather, jurisdiction for health and health care has been assigned using indirect powers.

The federal government derives its authority over matters of health and health care from the federal criminal law power3 and the federal spending power.4 The criminal law power is used mainly to enact legislation for public health and safety. Examples include the Food and Drugs Act, the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act and the Human Pathogens and Toxins Act. The federal government relies on the spending power to provide financial transfers to the provinces under the Federal-Provincial Fiscal Arrangements Act 5 (FPFAA) and to set standards and conditions under the Canada Health Act (CHA).6

Except for matters that fall under the powers described above, health is for the most part an area of provincial jurisdiction. For example, the provinces have jurisdiction over hospitals and health care services, the practice of medicine, the training of health professionals and the regulation of the medical profession, hospital and health insurance, and occupational health. Power over these areas is granted by sections 92(7) (hospitals), 92(13) (property and civil rights) and 92(16) (matters of a merely local or private nature) of the Constitution Act, 1867.

The CHA7 was passed by Parliament in 1984 and came into force the following year; the long title is An Act relating to cash contributions by Canada and relating to criteria and conditions in respect of insured health services and extended health care services. As the long title indicates, the CHA addresses federal funding for insured and extended health care services.

Section 3 of the CHA sets out the primary objective of the Government of Canada's health care policy, which is “to protect, promote and restore the physical and mental well-being of residents of Canada” and to ensure that access to services is reasonably facilitated “without financial or other barriers.” Sections 7 to 12 indicate that the purpose of the CHA is to establish the criteria and conditions that must be met under provincial law to qualify for the federal contribution. With respect to the criteria, the insurance program of each province must be:

In addition, section 13 of the CHA sets out the conditions that the provinces must satisfy to qualify for the full cash contribution that is part of the Canada Health Transfer (CHT). The conditions require that the provinces:

Under section 5 of the CHA, “as part of the Canada Health Transfer, a full cash contribution is payable by Canada to each province for each fiscal year.” The CHT, established under the FPFAA, is the largest of the transfer programs.8 The federal government can withhold some of a province's CHT if it is determined that the CHA has been contravened in that jurisdiction. In terms of penalties, provinces can be subject to a dollar-for-dollar deduction of the CHT if a medical practitioner in that province is found to have applied user charges or extra billing for insured services, which is prohibited under sections 18 and 19 of the CHA. As well, a CHT deduction amount to be determined by the Minister of Health can be applied to a province for contravening any of the conditions or criteria set out in sections 8 to 13 of the CHA.

The formula for calculating the CHT is provided in the FPFAA, which is amended when there are changes to this formula.9 Under section 24.21 of the FPFAA, cash payments to the provinces are allocated on an equal per capita basis. Beginning in the 2017–2018 fiscal year, the CHT payments increase by an amount equal to the three‑year moving average of Canada's nominal gross domestic product, but not less than 3% per year.10

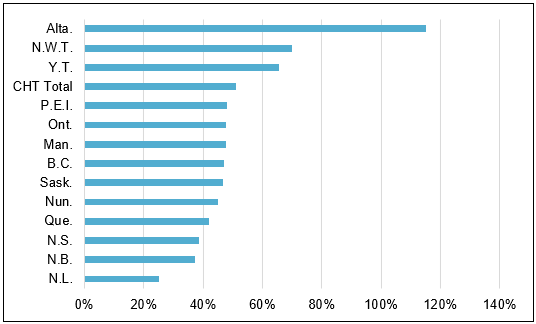

Figure 1 below shows the percentage increases in health transfer amounts to Canadian provinces over the past decade.

Figure 1 – Percentage Increase of Canada Health Transfers to the Provinces, 2012–2013 to 2021–2022

Note: “CHT Total” represents all Canada Health Transfer amounts.

Source: Figure prepared by the Library of Parliament using data obtained from Government of Canada, Major Federal Transfers.

As mentioned above, the public funds spent on health care include both federal and provincial sources. Figure 2 illustrates how the percentage of public health funding contributed by the CHT increased from 21% in 2012 to 23.5% in 2019.

Figure 2 – Percentage of Public Health Expenditures Covered by the Canada Health Transfer, 2012–2019

Sources: Figure prepared by the Library of Parliament using data obtained from Government of Canada, Major Federal Transfers; and Canadian Institute of Health Information, National Health Expenditure Trends, 1975–2019: Data Tables – Series A (by sector).

In addition to providing an annual contribution to the provinces through the CHT, the federal government can also provide directed funds for health care. However, directed funds generally cover a specific period of time, with no commitment to continue the funding indefinitely. Unlike the CHT and other major federal transfers, this type of transfer to the provinces and territories has no legislative basis; rather, the federal government enters into agreements with each jurisdiction on the amount to be transferred and on how the funds are to be spent.

The 2017 federal budget included $11 billion in funding to the provinces over 10 years, beginning in the 2017–2018 fiscal year, to be directed specifically to two areas: home care and mental health initiatives.11 All provinces except Quebec have agreed to A Common Statement of Principles on Shared Health Priorities,12 and the federal government has entered into bilateral agreements with each province.13 Quebec's asymmetrical agreement with the federal government is based on the 2004 arrangement.14

Total spending on health care has risen steadily in Canada since 1975, the first year for which the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) has data. According to a 2019 CIHI report, total annual health expenditures increased from $100 billion to $200 billion between 2000 and 2011, and reached an estimated $264.4 billion in 2019. At that time, according to the same report, health spending per Canadian could reach $7,068 in 2019, an increase over 2018 of almost $200. Total health spending as a percentage of gross domestic product has also risen significantly since 1975, from 7% to more than 11% in 2019.15

According to the 2019 CIHI report, in 2017, health spending per capita for infants was the highest for all age groups, except the 80‑years‑and‑over age group. Although health spending per capita after the age of one increases throughout a person's life, spending accelerates dramatically after the age of 60. Until that age, annual per capita health spending is below $5,000; after that age, spending increases to almost $30,000 by the age of 90. The proportion of elderly people in Canada has been rising since 2010, when the first of the baby boomers reached the age of 65. However, CIHI determined that the aging population has not been the primary cost driver in the rise in health care spending in recent years. CIHI estimated that the aging population accounted for 0.8% of the 3.8% increase in health care expenditures in 2019, while inflation and population growth accounted for 2.6%. Health sector inflation, health system efficiency and changes in technology and service utilization are other factors that contribute to the increase.16

In the 2019 CIHI report, data on where health dollars are spent indicates that most spending is on hospitals, physicians and drugs (prescription and non-prescription); together, these expenditures accounted for 57% of total health spending in 2019. The proportion of health care dollars spent on hospital services decreased from almost 45% in 1975 to 26.6% in 2019. This pattern reflects the increased number of treatments that can be provided outside of hospitals, as well as shorter hospital stays. While the proportion of health care dollars spent on physician services has fluctuated only slightly during that time frame at approximately 15%, the proportion spent on drugs has increased from about 9% in 1975 to 15.3% in 2019, reflecting the move away from hospital care to pharmaceutical care. Additional categories of health spending include other institutions, such as long-term care facilities, and other professional services, such as dental and vision care.17

Total health care spending includes funds from both public and private sources. In Canada, health care dollars from the public sector come largely from the provincial and federal governments in the form of tax dollars, but also from municipal government, workers' compensation boards and social security contributions. In its 2019 report, CIHI's forecast indicates that the proportion of health expenditures from public funds has been relatively steady since 2000, at about 70%. In 2019, public sources comprised 65.1% provincial financing (which includes the federal CHT) and 5.3% direct federal government, municipal government and social security funds, which amounts to 70.4% of total health expenditures. Private sector funding for health care, which accounts for the remaining 29.6% of health expenditures, includes primarily private insurance and out-of-pocket spending. In 2017, out-of-pocket spending accounted for $970 per capita, representing an average annual growth rate of 2.2% since 1988. Health care funding from private insurance stood at $824 per capita in 2017, for an annual growth rate of 4.1% over the same period.18

Figure 3 presents a comparison of Canada and other Organisation for Economic Co‑operation and Development (OECD) countries in terms of the public sector's share of health expenditures. In 2018, Norway, Luxembourg, Sweden and Denmark had the highest proportion of public sector health spending at about 84% of total health expenditures. Switzerland and the United States had the lowest proportion of publicly funded health care, accounting for 30% and 50% of total health expenditures, respectively.19

Figure 3 – Public Financing as a Percentage of Total Health Spending, 2018 or Nearest Year

Note: “Government” means government transfers or contributions largely from tax revenues. “Social Insurance” refers to other public programs, including social security.

Source: Figure prepared by the Library of Parliament using data obtained from Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, “Revenues of health care financing schemes [for 2018],” OECD.Stat (database), accessed 29 December 2020.

In July 2020, Canada's premiers agreed to the federal-provincial Safe Restart Agreement, which will provide $19 billion to the provinces to respond to future waves of COVID-19 and to restart their economies. Although the agreement is not specific to health care funding, it provides federal funds to the provinces to address some of the additional health care costs associated with the pandemic. This includes additional funds for contact tracing, testing, data management and personal protective equipment, as well as support for increasing the capacity of the health care system and addressing gaps in mental health and addiction services.20

Canada's premiers met with the prime minister on 10 December 2020 to discuss increasing the proportion of public health expenditures covered by the CHT. Although the prime minister made no commitment at that time, according to the premiers, he acknowledged that the “federal government needs to do more.” 21

Canada's health care system is funded primarily through federal and provincial public dollars. The federal contribution is made through the Canada Health Transfer and it accounts for about 23% of the public funds. The federal government has also committed directed funding over ten years for mental health and home care beginning in 2017. While almost 75% of health care costs are covered by public funds, the remaining portion is paid through private dollars. Although this ratio of public and private funding for health care is comparable to that of many countries, the public share of health care funding in some countries is as high as 85%. In July 2020, the federal government signed the federal-provincial Safe Restart Agreement which includes funding for the provinces to address some of the additional health care costs associated with the COVID-19 pandemic.

† Library of Parliament Background Papers provide in-depth studies of policy issues. They feature historical background, current information and references, and many anticipate the emergence of the issues they examine. They are prepared by the Parliamentary Information and Research Service, which carries out research for and provides information and analysis to parliamentarians and Senate and House of Commons committees and parliamentary associations in an objective, impartial manner. [ Return to text ]

© Library of Parliament