This HillStudy presents a non-exhaustive overview of the language regimes in place in the provinces and territories, and it briefly describes the main features of each one.

In Canada, jurisdiction over language is shared between the various levels of government. The federal government has adopted a bilingual language regime in which the two official languages are English and French. Although it has established its own support measures, it relies on the provinces and territories to help ensure that the two official languages are recognized across the country. In addition, efforts are being made by the federal, provincial, territorial and Indigenous governments to support Indigenous languages, which are not recognized as official languages, except in the Northwest Territories and Nunavut.

Each province and territory has its own language regime. This language regime is established through various official documents, including the Constitution, legislation, regulations, policies and strategic plans. It may apply to different areas, like the offer of government services, the adoption of legislation, justice, education and municipal services, to name a few.

Over the years, numerous efforts have been made across Canada to promote the recognition of English and French and to improve the offer of service to the public in both languages. In addition, a growing number of provincial and territorial initiatives are in place to enhance the vitality and support the development of official language minority communities. Moreover, a number of provincial and territorial governments have updated their legislative, regulatory and policy instruments to adapt to the evolving language needs of their respective populations. Nonetheless, depending on where they live, Canadians experience significant gaps in the types of service they can receive in the official language of their choice.

The various language regimes in place across Canada enhance each other and they are constantly required to change, as seen in the recent legislative updates made in Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and the Northwest Territories, the review of Nunavut legislation that is currently underway and the adoption of the first ever policy on French language services in British Columbia.

Intergovernmental collaboration has also ramped up. In fact, various partnership mechanisms at the regional, national and international levels aim to improve the offer of service in English and in French.

In June 2023, Parliament modernized the federal Official Languages Act by adopting An Act for the Substantive Equality of Canada’s Official Languages. The federal language regime now emphasizes the importance of cooperation among the various levels of government and recognizes that the diversity of language regimes helps achieve substantive equality between English and French in Canada. As well, the Government of Canada acknowledges that its official languages legislation does not infringe on Indigenous language rights and that it does not stand in the way of revitalizing these languages.

In recent years, Indigenous peoples across Canada have taken part in initiatives to revitalize their languages affected by assimilation policies. The federal government has recognized the importance of reclaiming, revitalizing, maintaining and strengthening Indigenous languages through Canada’s Indigenous Languages Act, which was passed in 2019. Although the Act facilitates the exercise of their Indigenous language rights, Indigenous peoples are also critical of the legislation. In some cases, provincial, territorial and Indigenous governments have also taken action to support the efforts of Indigenous peoples in this regard.

In Canada, the Constitution does not contain any provision on jurisdiction over language. In a 1988 decision, the Supreme Court of Canada asserted:

Language is not an independent matter of legislation but is rather “ancillary” to the exercise of jurisdiction with respect to some class of subject matter assigned to Parliament or the provincial legislatures by the Constitution Act, 1867.1

The power to legislate in the area of language, therefore, belongs to the various levels of government, under their respective legislative authorities.

The provinces and territories have an important role to play in protecting official language minorities in sectors that come under their exclusive or shared jurisdictions. Practices are continually evolving, as evidenced in 2013 by the coming into force of Nunavut’s Official Languages Act and Inuit Language Protection Act, both currently being reviewed by the Legislative Assembly.2 In the Maritimes, Prince Edward Island revised its language regime that same year, then added designated services in French about 10 years later.3 New Brunswick followed suit in 2013, and it once again began to revise its Official Languages Act in 2021, which resulted in other legislative changes in 2023.4 Newfoundland and Labrador adopted its French Language Services Policy in 2015.5 In 2024, Nova Scotia revised the language legislation it had adopted 20 years earlier.6

In the Western provinces, Manitoba’s The Francophone Community Enhancement and Support Act came into force in 2016, while Alberta adopted its French Policy in 2017 and reviewed it a few years later.7 British Columbia adopted its first French Language Policy in 2024.8 Meanwhile, Ontario, Quebec and the Northwest Territories updated their respective language legislation between 2021 and 2023.9

During the 43rd and 44th Parliaments, the federal government introduced bills to modernize the federal Official Languages Act, in particular to recognize the diversity of provincial and territorial language regimes and their contribution to advancing the equality of status and use of English and French in Canadian society. An Act for the Substantive Equality of Canada’s Official Languages, which recognizes the importance of working with the provincial and territorial governments, was assented to in June 2023.10 Every 10 years, the federal government is required to review its Official Languages Act, including the provisions on collaboration with its provincial and territorial counterparts, and conduct a comprehensive analysis of the language situation in various sectors within its jurisdiction.11

Although Indigenous languages are not recognized as official languages except in the Northwest Territories and Nunavut, they receive support from the various levels of government, including Indigenous governments. At the federal level, the language regime that governs Indigenous languages complements the official languages regime.12 Since 2019, the Indigenous Languages Act recognizes the importance of supporting Indigenous peoples in their efforts to reclaim, revitalize, maintain and strengthen Indigenous languages.13 However, this federal legislation has been criticized by Indigenous peoples, particularly as regards the absence of a whole of government approach.14 A three-year parliamentary review of its provisions is planned, but has not yet taken place.15 In 2023, it was determined that nothing in the Official Languages Act affects Indigenous languages or impedes the revitalization of these languages.16

Among the provinces and territories, legislative, political and strategic initiatives to recognize or revitalize Indigenous languages have been introduced in 10 legislatures. Financial support is also available across Canada to bolster the efforts of Indigenous peoples in this matter, as are various policies, programs and agreements.17 However, the federal contribution is seen as insufficient, particularly in terms of support for the efforts of provincial, territorial or Indigenous governments.18

This HillStudy summarizes the existing provincial and territorial language regimes, as well as current practices in intergovernmental collaboration. Although it addresses the main features of these regimes, it is not considered exhaustive.

This section describes the features of the language regimes established by the provinces and territories. The following aspects are examined:

The main characteristics of these language regimes are summarized using figures and tables.

Language regimes vary significantly from one province or territory to another. Only Quebec and Manitoba were subject to language obligations when they joined Confederation. In 1969, New Brunswick broke new ground by adopting the first Official Languages Act. All provinces and territories have measures in place that relate to English, to French or to both languages.

In terms of Indigenous languages, the language regimes are more recent and are being developed according to the specific circumstances of each of the peoples concerned.

The minority language can be used in the course of debates and proceedings in nine legislative assemblies.

Eight provinces and territories also have provisions for printing and publishing legislation in the minority language.

In the territories, rights are conferred on Indigenous languages in their respective legislatures.29 In the Northwest Territories and Nunavut, provisions exist for the legislation or documents of the Legislative Assembly.30 In Ontario, the use of Indigenous languages is permitted without being enshrined in legislation.31 In Manitoba, a pilot project provides for the translation of Hansard in one of the seven recognized Indigenous languages.32 In addition, some Indigenous governments allow the use of Indigenous languages in their legislatures.33

In the area of education, every province and territory has implemented legislative measures to comply with the criteria set out in the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.34 Section 23 of the Charter guarantees the right of parents to have their children receive primary and secondary school instruction in the minority language, where warranted by numbers. It also guarantees parents the right to administer minority language schools.35

Since 1970, the federal government has offered financial support to the provinces and territories to cover the additional costs incurred for minority-language education and second-language instruction. Funding for education is managed through an agreement signed by the Government of Canada and the Council of Ministers of Education (Canada). Each province and territory establishes its own action plan which contains funding commitments and performance indicators.36

That said, only five provinces address education in the official documents that govern their language policies: New Brunswick,37 Quebec, Ontario,38 Manitoba and Alberta. In British Columbia, education has been identified as a priority sector in the implementation plan for its French Language Policy.

The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples recognizes the rights of Indigenous peoples with regard to education.39 The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act of 2021 confirms that this universal international instrument applies in Canada.40 Consequently, the federal government provides financial support to promote Indigenous language learning in schools.41 It is also responsible for school administration on First Nations reserves.42 In addition, self-government agreements and treaties specify the Indigenous education obligations.43 In the provinces and territories, various measures exist to support primary and secondary education in Indigenous languages.

In the area of justice, section 530 of the Criminal Code56 guarantees the right of every accused in criminal proceedings to be tried in their language of choice. The provinces and territories, which must comply with this requirement have, for the most part, adopted legislative provisions to that effect and implemented other measures to oversee language rights in their courts.

In 2019, the federal Divorce Act was amended to allow the parties to choose the official language in which to hold their divorce proceedings.63 The amendments, although adopted by the Parliament of Canada, will gradually apply to every province and territory.64

The language legislation of Nunavut and the Northwest Territories allows the use of Indigenous languages in territorial courts and in civil cases. In Quebec, rights exist to use the Cree, Inuit or Naskapi languages in certain judicial districts covered by modern treaties, particularly with regard to interpretation and translation services.65 In Alberta, a strategy of the Alberta Court of Justice identifies priorities for Indigenous justice and addresses issues with interpretation in Indigenous languages.66

Elsewhere, some provincial courts have adopted initiatives that are not official laws, policies or strategies. Below are a few examples:

In the health sector, a majority of the provinces and territories have adopted legislative, regulatory or strategic provisions.

In Nunavut, the Inuit Language Protection Act guarantees that health, medical and pharmaceutical services are provided in the Inuit language.72 In Quebec, the Cree, Inuit and Naskapi populations manage and provide health and social services in their respective territories. Legislation promotes access to services in Indigenous languages and encourages cultural safety in all facilities of the health and social services network.73 Moreover, most provinces and territories offer translation or interpretation services in Indigenous languages in certain designated health facilities and on a larger scale.74

Although every province and territory has taken measures regarding the offer of government service in the minority language, Quebec has made the offer of service in the majority language a priority. That said, the extent of these obligations varies from place to place.

The offer of government services in Indigenous languages is protected in four places.

Some provinces and territories have defined language obligations that relate to the offer of municipal services.

Elsewhere in Canada, some municipalities have bilingual status or provide service in both official languages, namely, in Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia, Saskatchewan, Alberta and the Northwest Territories, without the province or territory having had to prepare a corresponding legislative, regulatory or policy framework.

In some provinces, municipalities have formed associations to maintain and deliver municipal services in French. These include, for example, the Association francophone des municipalités de l’Ontario, the Association francophone des municipalités du Nouveau-Brunswick and the Association of Manitoba Bilingual Municipalities.

Nunavut has established rights and obligations concerning the Inuit language at the municipal level in the Inuit Language Protection Act. As indicated above, the territory’s Official Languages Act and strategic plan provide for the offer of service in the official languages in municipalities where significant demand exists. In Quebec, the right to use the Cree, Inuit or Naskapi languages exists in the regions covered by modern treaties, and certain Indigenous peoples have the opportunity to receive municipal services in English.83

Some provincial and territorial legislation, policies and strategies contain provisions for the development of official language minority communities.

In Manitoba, The Francophone Community Enhancement and Support Act defines members of the francophone community as

those persons in Manitoba whose mother tongue is French and those persons in Manitoba whose mother tongue is not French but who have a special affinity for the French language and who use it on a regular basis in their daily life.92

The Act provides for a gradual increase in the offer of service in French to the public in order to enhance the vitality of Manitoba’s francophone community. The Act establishes an advisory council to advise the Minister responsible for Francophone Affairs on measures to be taken to that end. The Act encourages the representation of Manitoba’s francophone community on the boards of government agencies. Moreover, collaboration and dialogue are two of the fundamental principles on which implementing this law is based.93

As mentioned above, the language legislation of Nunavut and of the Northwest Territories contains provisions regarding Indigenous communities.

The federal Official Languages Act established the position of Commissioner of Official Languages which was created in 1970. Three provinces (Ontario, New Brunswick and Quebec) and two territories (the Northwest Territories and Nunavut) also established their own language commissioners. Their role is to ensure that their province or territory complies with both the official languages legislation and measures for the provision of French-language services in a minority setting – or, in Quebec, a majority setting – and to review complaints about these matters. At times, informal discussions are held between the provincial or territorial commissioners and the federal Commissioner of Official Languages.101

In Prince Edward Island, the French Language Services Act does not create an office of the commissioner or ombudsman; instead, it prescribes the appointment of a complaints officer accountable to the Minister Responsible for Acadian and Francophone Affairs. Under the existing process, complaints are first addressed by the French language services coordinator of the government institution involved in the incident, then referred to the Complaints Officer, when necessary. In Manitoba, The Francophone Community Enhancement and Support Act gives the Francophone Affairs Secretariat the mandate to address public concerns regarding access to services in French. The Secretariat handles complaints from the public filed under the French Language Services Policy.

While Yukon does not have a language commissioner or ombudsman, redress can be sought for a violation of rights established in the Languages Act. A right to redress is also provided in the language legislation of the Northwest Territories, Nunavut and New Brunswick.

At the federal level, the Indigenous Languages Act created the Office of the Commissioner of Indigenous Languages, which opened in 2021. As indicated above, the language commissioners of the Northwest Territories and Nunavut also have a mandate to promote and protect the language rights of the Indigenous population. In Nunavut, a separate entity, the Inuit Uqausinginnik Taiguusiliuqtiit, has jurisdiction over services provided in the Inuit language.

Some language legislation designates a minister responsible for developing or coordinating policies and programs relating to services in French. This is the case in the Northwest Territories, Nunavut, Manitoba, Ontario, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island. Elsewhere, while the role of the minister responsible may be mentioned in language policy, no legislation exists to support it. In Quebec, the Minister of the French Language is designated in the Charter of the French Language as being responsible for the protection of French, but the Minister Responsible for Relations with English-Speaking Quebecers does not have an equivalent designation in legislation.

In Nunavut, the Minister of Languages, and in the Northwest Territories, the Minister Responsible for Official Languages have responsibilities that extend to Indigenous languages. In addition, some Indigenous governments appoint a minister responsible for languages.104

In Canada, more than 70 spoken Indigenous languages were identified in 2021, although this number is constantly shrinking, and experiences with the vitality of these languages vary from one region to another across the country.105 Indigenous peoples have taken part in initiatives to revitalize their languages hindered by policies of assimilation, such as Indian residential schools. These initiatives were strengthened following the work of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, whose full final report published in 2015 drew attention to the urgency of reinforcing Indigenous language rights.106 Indigenous peoples receive support from the federal government and from some provincial, territorial and Indigenous governments, in particular, through legislative measures.

The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples recognizes the rights of Indigenous peoples with regard to language and culture.107 In 2021, the federal government passed the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act which constitutes a framework for implementing these rights.108 The action plan for implementing this legislation includes a series of commitments to Indigenous peoples’ language and cultural rights.109 A Senate committee studied the implementation of this Act and action plan, but had not tabled its findings at the time of revising this HillStudy.110

Meanwhile, in 2019, the federal government recognized, in its Indigenous Languages Act, the importance of supporting Indigenous peoples in their efforts to reclaim, revitalize, maintain and strengthen Indigenous languages.111 However, recent reviews of the implementation of this Act have shown that more effort is needed to fund the revitalization of Indigenous languages and to support the work of Indigenous peoples through initiatives led by and for them at the local level.112

In the provinces and territories, although legislation in the Northwest Territories and in Nunavut grants official status to Indigenous languages, legislative measures to recognize or revitalize these languages have been taken in four other legislatures.

Some self-government treaties or agreements contain provisions to protect Indigenous languages and cultures. Consequently, Indigenous peoples covered by modern treaties may have the jurisdiction needed to legislate the protection of their languages and cultures.122 In addition, some provinces offer financial support for initiatives to revitalize Indigenous languages.123

For a few years now, calls to give Indigenous languages official status have grown. In the mid-1990s, a report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples recommended that the Indigenous peoples be given the discretion to make Indigenous languages the official languages of their nations, territories and communities.124 In the mid-2000s, another report, prepared by the Task Force on Aboriginal Languages and Cultures, discussed the status of these languages.125 Then, debates were held at the federal level between 2019 and 2024.126 In a call for justice, the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls focused on recognition by all governments of the official status of Indigenous languages and the importance of promoting and supporting their revitalization.127 Certain academics also contributed to this discussion.128

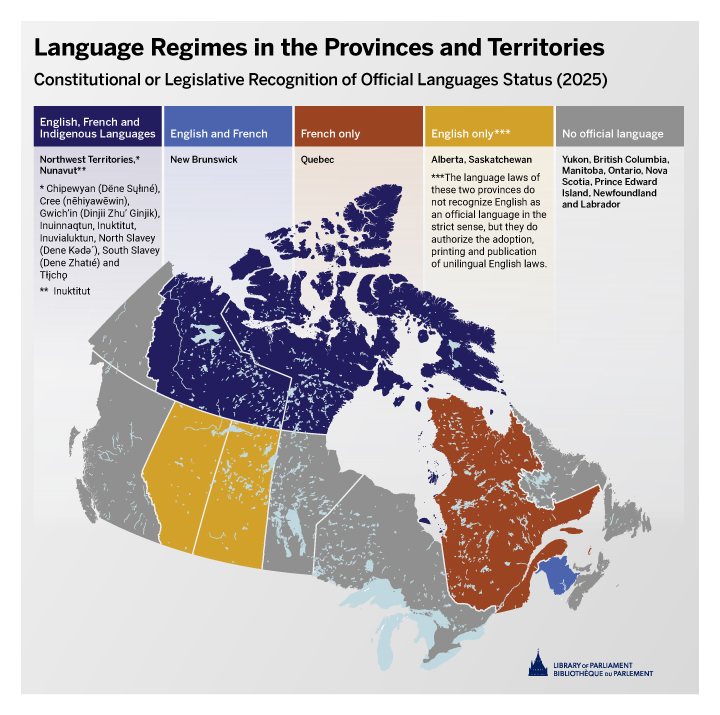

Figure 1 details the constitutional or legislative recognition of the status of official languages in the provinces and territories. Legislation in the Northwest Territories and in Nunavut recognizes the official status of English, French and Indigenous languages. Under the Constitution and its provincial legislation, New Brunswick is the only officially bilingual province. Quebec recognizes only French as an official language. Alberta and Saskatchewan do not recognize English as an official language in the strict sense, but they do authorize the adoption, printing and publication of unilingual English legislation. Everywhere else, no language has official status.

Figure 1 – Constitutional or Legislative Recognition of Official Language Status, 2025

Sources: Figure prepared by the Library of Parliament using data obtained from provincial and territorial government websites.

Table 1 provides a non-exhaustive list of the official documents of each province and territory on the recognition of English or French, the offer of service in the minority language or the development of official language minority communities.

| Province or Territory | Official Documents |

|---|---|

| Yukon |

|

| Northwest Territories |

|

| Nunavutb |

|

| British Columbia |

|

| Alberta |

|

| Saskatchewan |

|

| Manitoba |

|

| Ontario |

|

| Quebec |

|

| New Brunswick |

|

| Nova Scotia |

|

| Prince Edward Island |

|

| Newfoundland and Labrador |

|

Notes:

a. Only adoption dates are provided in the table for laws, regulations and policies; in some cases, changes may have been made after those dates. For strategic plans, all relevant dates are shown in the table.

b. The first Official Languages Act of 1988 referred to here is the one in force in the Northwest Territories when Nunavut was created in 1999. It was repealed when the 2008 Official Languages Act was enacted by Nunavut.

Source:

Table prepared by the Library of Parliament using data obtained from provincial and territorial government websites.

Table 2 provides a non-exhaustive list of the official documents of the provinces and territories on the recognition or revitalization of Indigenous languages. It does not include initiatives by Indigenous governments. To date, seven provinces and three territories have adopted legislative measures, policies or strategic plans in that regard.

| Province or Territory | Official Documents |

|---|---|

| Yukon |

|

| Northwest Territories |

|

| Nunavut b |

|

| British Columbia |

|

| Alberta |

|

| Saskatchewan |

|

| Manitoba |

|

| Ontario |

|

| Quebec |

|

| Nova Scotia |

|

Notes:

a. Only adoption dates are provided in the table for laws; in some cases, changes may have been made after those dates. For strategic plans or frameworks, all relevant dates are shown in the table.

b. The first Official Languages Act of 1988 referred to here is the one in force in the Northwest Territories when Nunavut was created in 1999. It was repealed when the 2008 Official Languages Act was enacted by Nunavut.

Source:

Table prepared by the Library of Parliament using data from provincial and territorial government websites.

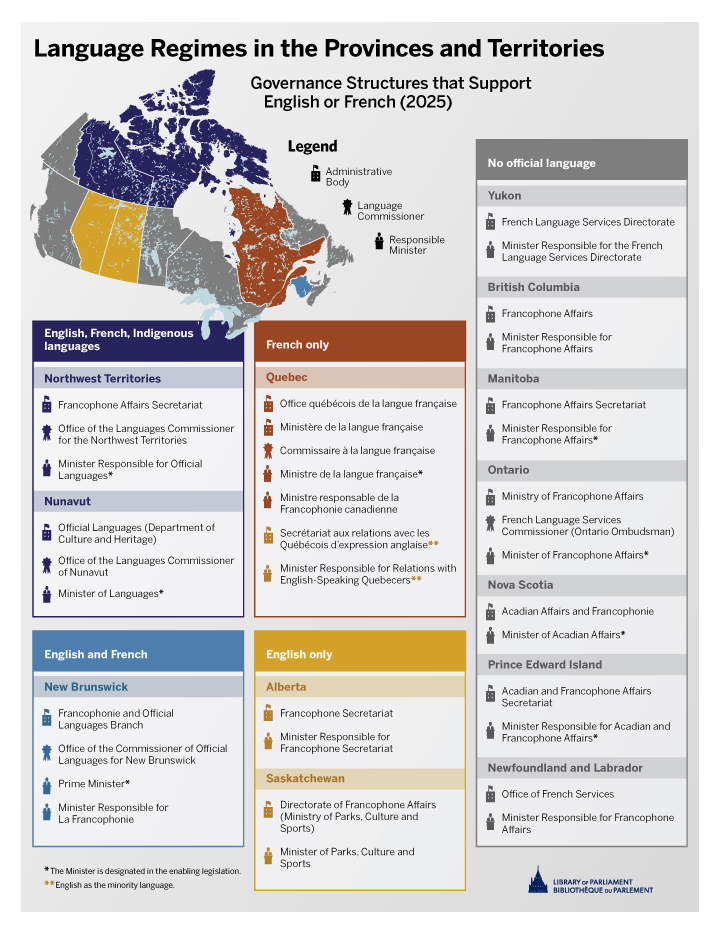

Figure 2 lists, for each province and territory, the administrative entities, language commissioners and ministers responsible for protecting English or French, providing services in the minority language or maintaining relationships with official language minority communities.

Figure 2 – Governance Structures that Support English or French, 2025

Sources: Figure prepared by the Library of Parliament using data obtained from provincial and territorial government websites.

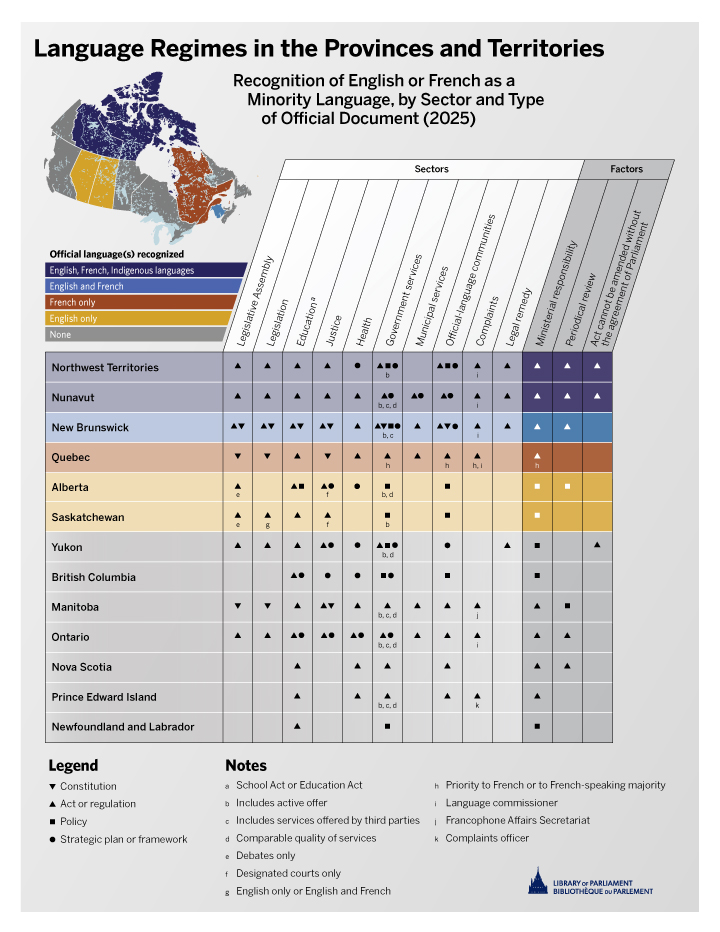

Figure 3 details the recognition of English or French as a minority language in the provinces and territories, by sector and type of official document.

Figure 3 – Recognition of English or French as a Minority Language, By Sector and Type of Official Document, 2025

Source: Figure prepared by the Library of Parliament using data obtained from provincial and territorial government websites.

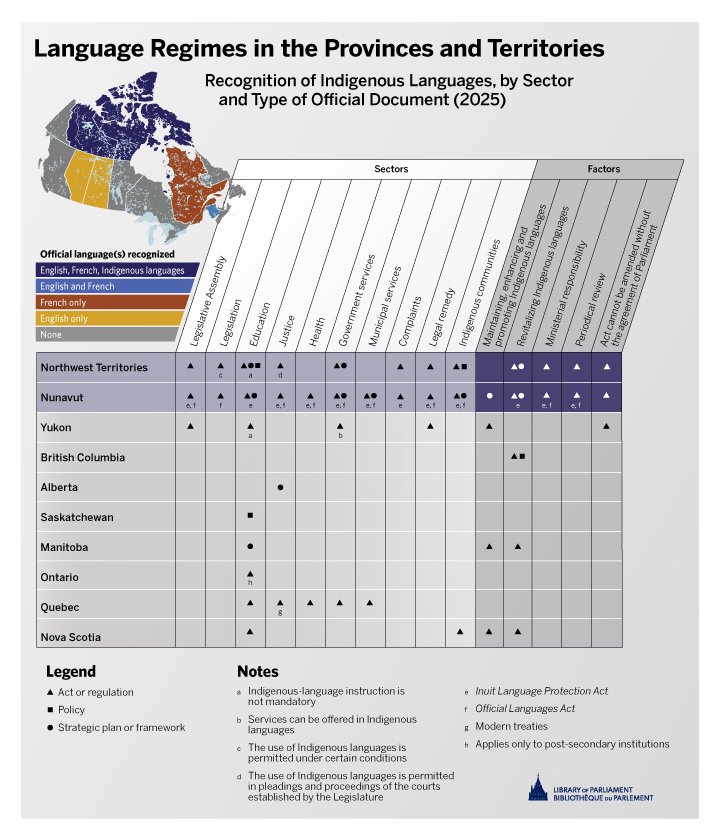

Figure 4 details the recognition of Indigenous languages in the provinces and territories, by sector and type of official document. It does not take into account initiatives by Indigenous governments.

Figure 4 – Recognition of Indigenous Languages, By Sector and Type of Official Document, 2025

Source: Figure prepared by the Library of Parliament using data obtained from provincial and territorial government websites.

This section describes current practices in place for intergovernmental cooperation, mainly as it concerns the protection of French as a minority language.

Beginning in the mid-1990s, it became a regular occurrence for the federal government to sign cooperation agreements with the governments of the provinces and territories to promote French-language services in those provinces and territories.129 The purpose of these agreements was to increase the capacity of provincial and territorial governments to develop, improve and provide services in the language of the minority, including municipal services.

The funding invested has helped to support the implementation of provincial and territorial legislation. It also encourages the delivery of services in all areas (other than education) deemed essential to the development of official language minority communities (e.g., justice, health, youth, arts, culture). Each province and territory establishes a strategic plan that describes the actions planned and the results expected.

The provincial and territorial governments have all set up offices responsible for francophone affairs or, in Quebec, francophone or anglophone affairs. In most cases, the office comes under the responsibility of the designated minister; in some cases, it comes under another ministerial portfolio (e.g., a provincial secretariat or intergovernmental affairs). In Quebec, relations with English-speaking residents have been managed by a secretariat of its Ministère du Conseil exécutif since November 2017.

In each one of its five-year initiatives since 2003, the federal government has reiterated the importance of intergovernmental cooperation and support for the offer of service in both official languages in the provinces and territories.130 An Act for the Substantive Equality of Canada’s Official Languages was passed by Parliament in June 2023 enshrined the importance of this cooperation in the federal Official Languages Act.131 It also enshrined in the Act the commitment to protect and promote French across Canada.132

Since the late 1980s, the Quebec government has signed cooperation agreements with the governments of other provinces and territories to help them improve their offer of service in French.133 The sectors, by priority, are culture, communications, education, economic development and health. Help is also provided in other sectors, such as early childhood services, youth, immigration, justice, tourism and any other sector deemed relevant.

In 2006, Quebec updated its policy on the Canadian Francophonie to strengthen solidarity between francophones in Quebec and those elsewhere in Canada.134 In 2017, it unveiled its Policy on Québec Affirmation and Canadian Relations, which puts Canada’s Francophonie at the centre of the dialogue between Quebec and the rest of Canada.135 In 2022, the province again updated its policy on the Canadian Francophonie and launched an action plan for its implementation.136 In addition, as of 1 June 2022, its language legislation contains references to Canada’s francophone and Acadian communities.137 Youth mobility, access to post-secondary education and research in French, partnerships in the fields of health and economics, and the creation of the Journée de la francophonie canadienne are among the targeted areas for action.

Since 1994, the provinces and territories have participated annually in the Ministers’ Council on the Canadian Francophonie (formerly the Ministerial Conference on the Canadian Francophonie).138 This entity is committed to strengthening intergovernmental cooperation on issues related to francophone affairs in Canada. It also seeks to improve the coordination of provincial and territorial actions with federal government actions. Each province and territory is represented on the Council by a minister responsible for francophone affairs. The federal government has been represented since 2005.

At their most recent annual meetings, provincial and territorial ministers examined various issues, including francophone immigration, the offer of service in French, the modernization of the federal Official Languages Act and the shortage of bilingual workers. They called for increased cooperation with the federal government following the Action Plan for Official Languages 2023–2028: Protection–Promotion–Collaboration, which provides $137 million in funding over five years to support intergovernmental cooperation for services in the minority language, an increase of nearly 70% over 2018–2023.139

In its official languages reform document released in February 2021, the federal government proposed to “recognize the mandate, collaboration and action of the Ministerial Council on the Canadian Francophonie,” but this proposal was not carried into An Act for the Substantive Equality of Canada’s Official Languages, which was passed by Parliament in June 2023.140

Quebec and New Brunswick are members of the Organisation internationale de la Francophonie.141 Their participation gives them the political leverage needed to influence a number of international issues that relate to the Francophonie. Ontario and Nova Scotia have observer status – since November 2016 and October 2024 respectively – which allows them to attend meetings of the official entities of the Francophonie, but not to take part in debates. The other provinces and territories are represented by the federal government, which has member status.142 Moreover, three francophone organizations from civil society are members of the Conference of International Non-Governmental Organisations and accredited special partners of La Francophonie: the Fédération des communautés francophones et acadienne du Canada, the Fédération culturelle canadienne-française and the Société Nationale de l’Acadie.143

At the municipal level, some municipalities of Quebec, along with the Association francophone des municipalités du Nouveau-Brunswick, are members of the Association internationale des maires francophones, an international network of locally elected representatives from countries in which French is formally recognized.144

In terms of Indigenous languages, the Inuit Circumpolar Council supports the protection and promotion of Inuit languages internationally.145 In addition, an arrangement made in 2022 between the Government of Canada and the Government of New Zealand emphasizes Indigenous collaboration, with particular regard for the preservation and revitalization of languages.146

Provincial and territorial language regimes are constantly evolving. They sustain each other through public pressure, changes that arise in Canadian society and case law. Practices for intergovernmental collaboration follow the same pattern, with an increasingly evident need for ongoing partnerships between different levels of government. The federal government must be able to count on the support of its provincial and territorial counterparts, to a certain extent, to ensure Canada-wide recognition of the two official languages and to foster the development of official language minority communities.

In recent years, efforts have also been made across Canada to augment the protection and revitalization of Indigenous languages, albeit unevenly. Indigenous peoples are carrying out their own initiatives with the support of the various levels of government. However, this support is considered insufficient by the Indigenous peoples themselves. As it does for protecting and promoting Canada’s two official languages, the federal government can set an example among its provincial and territorial counterparts and encourage partnerships with Indigenous governments to help Indigenous peoples reclaim and revitalize their languages.

In Manitoba, the Legislative Assembly passed The Francophone Community Enhancement and Support Act on 30 June 2016. The provision of French language services, previously protected by just a policy, now has a legislative framework. See Manitoba, The Francophone Community Enhancement and Support Act, C.C.S.M., c. F157.

In Alberta, the government released the French Policy on 14 June 2017 in order to help the provincial government departments improve their services in French and support the vitality of Alberta’s francophone community. This policy was updated in March 2023 and will be revised again in 2031. See Alberta, French Policy ![]() (771 KB, 10 pages); and Alberta, French Policy: Enhancing services in French to support the vitality of Alberta’s French-speaking communities

(771 KB, 10 pages); and Alberta, French Policy: Enhancing services in French to support the vitality of Alberta’s French-speaking communities ![]() (5.31 MB, 12 pages), March 2023.

(5.31 MB, 12 pages), March 2023.

In Ontario, the Build Ontario Act (Budget Measures) 2021, assented to on 9 December 2021, amended the French Language Services Act, notably to ensure the active offer of services in French and provide for a review every 10 years. See Ontario, Legislative Assembly, Bill 43, Build Ontario Act (Budget Measures), 2021, S.O. 2021, c. 40; and Ontario, French Language Services Act, R.S.O. 1990, c. F.32, ss. 5(1.1) and 16.

In Quebec, An Act respecting French, the official and common language of Québec, assented to on 1 June 2022, amended the Charter of the French Language to give French more prominence as the official and common language of that province. Provisions affecting the language of legislation, justice, labour, municipalities and post-secondary education could, according to some stakeholders, negatively affect the rights of Quebec’s English-speaking communities. Legal challenges to this effect have been initiated. Provisions relating to the language of justice have already been suspended. See Quebec, National Assembly, Bill 96, An Act respecting French, the official and common language of Québec, 42nd Legislature, 2nd Session (S.Q. 2022, c. 14); Quebec, Charter of the French Language, c. C‑11; and Mitchell v. Attorney General of Quebec, 2022 QCCS 2983 (CanLII).

In the Northwest Territories, the territorial government launched public consultations in spring 2022 and proposed amendments to the Official Languages Act that came into force in spring 2023. Meanwhile, the Standing Committee on Government Operations of the Legislative Assembly conducted its own review of the legislation. See Northwest Territories, Official Languages Act ![]() (430 KB, 23 pages), R.S.N.W.T. 1998, c. O-1; Northwest Territories, Have Your Say on the Northwest Territories Official Languages Act, News release, 16 May 2022; Northwest Territories, Department of Education, Culture and Employment, What We Heard Report: NWT Official Languages Act Engagement

(430 KB, 23 pages), R.S.N.W.T. 1998, c. O-1; Northwest Territories, Have Your Say on the Northwest Territories Official Languages Act, News release, 16 May 2022; Northwest Territories, Department of Education, Culture and Employment, What We Heard Report: NWT Official Languages Act Engagement ![]() (516 KB, 9 pages), May–June 2022; Northwest Territories, Legislative Assembly, Bill 63, An Act to Amend the Official Languages Act, 19th Legislature, 2nd Session; and Northwest Territories, Standing Committee on Government Operations, Report on the 2021–22 Review of the Official Languages Act

(516 KB, 9 pages), May–June 2022; Northwest Territories, Legislative Assembly, Bill 63, An Act to Amend the Official Languages Act, 19th Legislature, 2nd Session; and Northwest Territories, Standing Committee on Government Operations, Report on the 2021–22 Review of the Official Languages Act ![]() (2.24 MB, 41 pages), 27 March 2023.

(2.24 MB, 41 pages), 27 March 2023.

The federal Official Languages Act is a quasi-constitutional statute whose application derives from section 16(1) of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, which recognizes English and French as the official languages of Canada. See Official Languages Act, R.S.C. 1985, c. 31 (4th Supp.); and Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, Part I of the Constitution Act, 1982, being Schedule B to the Canada Act 1982, 1982, c. 11 (U.K.), s. 16(1).

The federal Indigenous Languages Act is based on the principle that “the rights of Indigenous peoples recognized and affirmed by section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982 include rights related to Indigenous languages.” See Indigenous Languages Act, S.C. 2019, c. 23, s. 6; and Constitution Act, 1982, being Schedule B to the Canada Act 1982, 1982, c. 11 (U.K.).

In 2021, the official languages reform document distinguished between the official languages regime and the Indigenous languages regime, while recognizing the complementary visions between the two regimes. See Government of Canada, English and French: Towards a substantive equality of official languages in Canada, 2021.

[ Return to text ]In the Northwest Territories, the languages with official status are English, French, Dëne Sųłıné (Chipewyan), Nēhiyawēwin (Cree), Dene Kǝdǝ́ (Northern Slavey), Dene Zhatıé (Southern Slavey), Dinjii Zhu’ Ginjik (Gwich’in), Inuinnaqtun, Inuktitut, Inuvialuktun and Tłįchǫ. See Northwest Territories, Official Languages Act ![]() (430 KB, 23 pages), R.S.N.W.T. 1998, c. O-1, s. 4.

(430 KB, 23 pages), R.S.N.W.T. 1998, c. O-1, s. 4.

In Nunavut, the languages with official status are English, French and Inuktitut. See Nunavut, Official Languages Act, C.S.Nu., c. O-20, s. 3 (CanLII).

[ Return to text ]Nova Scotia’s French-language Services Act provides for a review every 10 years. See Nova Scotia, An Act to Amend Chapter 26 of the Acts of 2004, the French-language Services Act ![]() (1.43 MB, 4 pages), 2024, c. 11.

(1.43 MB, 4 pages), 2024, c. 11.

In New Brunswick, the Official Languages Act prescribes a fixed review date of no later than 31 December 2031. Since this provision came into force in 2002, the legislation has been amended twice, in 2013 and in 2023. See New Brunswick, Official Languages Act ![]() (199 KB, 24 pages), S.N.B. 2002, c. O-0.5, s. 42(1).

(199 KB, 24 pages), S.N.B. 2002, c. O-0.5, s. 42(1).

In Ontario, the French Language Services Act provides for a review every 10 years and prescribes a fixed date for initiating the first review, no later than the end of 2031. See Ontario, French Language Services Act, R.S.O. 1990, c. F.32, s. 16(3).

In the Northwest Territories, the Official Languages Act provides that the Legislative Assembly, or a committee designated or established by it, shall review the Act periodically. The Standing Committee on Government Operations conducted such reviews in 2009, 2015 and 2022. The legislation was last amended on 30 March 2023. In the version in force prior to that date, a review was mandated after five years. In the current version, a review must be carried out within the first two years of the 21st Legislative Assembly, and then within the first two years of every second Legislative Assembly thereafter. See Northwest Territories, Official Languages Act ![]() (430 KB, 23 pages), R.S.N.W.T. 1998, c. O-1,s. 35(1).

(430 KB, 23 pages), R.S.N.W.T. 1998, c. O-1,s. 35(1).

In Nunavut, the Official Languages Act stipulates that a review be conducted every five years either by the Legislative Assembly or by one of its committees. This review also applies to the Inuit Language Protection Act. At the time of writing, a committee of the Legislative Assembly had reviewed both these Acts and reported its recommendations. Then, a bill reviewing both laws was tabled in the Legislative Assembly. See Nunavut, Official Languages Act, C.S.Nu., c. O-20, s. 37(1) (CanLII); Nunavut, Inuit Language Protection Act, C.S.Nu., c. I-140 (CanLII); Nunavut, Legislative Assembly, Standing Committee on Legislation, Report on the Review of Nunavut’s Language Legislation: Official Languages Act and Inuit Language Protection Act ![]() (233 KB, 7 pages), Winter 2024; and Nunavut, Legislative Assembly, Bill 76, An Act to Amend the Inuit Language Protection Act and the Official Languages Act

(233 KB, 7 pages), Winter 2024; and Nunavut, Legislative Assembly, Bill 76, An Act to Amend the Inuit Language Protection Act and the Official Languages Act ![]() (342 KB, 44 pages), 6th Legislative Assembly, 2nd Session [bilingual content].

(342 KB, 44 pages), 6th Legislative Assembly, 2nd Session [bilingual content].

In spring 2024, the Legislative Assembly of Ontario allowed the use of an Indigenous language during its debates for the first time. See Liam Casey, The Canadian Press, “‘Language is identity’: First Nation legislator to make history at Ontario Legislature,” CBC News, 26 May 2024.

The Parliament of Canada followed the same model by allowing the use of Indigenous languages in the House of Commons and the Senate without enshrining it in legislation. See Marie-Ève Hudon, Official Languages and Parliament ![]() (795 KB, 31 pages), Publication no. 2015-131-E, Library of Parliament, 15 March 2022, pp. 16–17

(795 KB, 31 pages), Publication no. 2015-131-E, Library of Parliament, 15 March 2022, pp. 16–17

See Mahe v. Alberta, [1990] 1 S.C.R. 342, which confirmed this interpretation of section 23 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

In recent years, several provinces have carried out school governance reforms. Minority school boards, divisions or commissions needed to be maintained in all cases. In Nova Scotia, for example, An Act Respecting the Conseil scolaire acadien provincial received Royal Assent on 9 November 2023. It recognizes the right of Acadians to school governance, requires consultation between the provincial government and the French-language school board, and creates a position dedicated to French first‑language education within the public administration. See Nova Scotia, An Act Respecting the Conseil scolaire acadien provincial ![]() (1.65 MB, 52 pages), 2023, c. 10.

(1.65 MB, 52 pages), 2023, c. 10.

In Quebec, the Court of Appeal stated in April 2025 that abolishing English-language school boards violated rights guaranteed in section 23 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. The Quebec government has filed an application with the Supreme Court of Canada to appeal this decision. See Procureur général du Québec v. Quebec English School Boards Association, 2025 QCCA 383 (CanLII); and Supreme Court of Canada, Case No. 41838.

[ Return to text ]Section 8(1) of the Inuit Language Protection Act states:

Every parent whose child is enrolled in the education program in Nunavut, including a child for whom an individual education plan has been proposed or implemented, has the right to have his or her child receive Inuit Language instruction.

This section was to come into force on 1 July 2019, but was temporarily suspended for students in grades 4 to 12 because of a lack of certified Inuit-language teachers. In 2020, amendments to this Act and Nunavut’s Education Act extended the timelines for a phased implementation of Inuit language education from 2026 to 2039. See Nunavut, Inuit Language Protection Act, C.S.Nu., c. I-140, s. 8(1) (CanLII); and Nunavut, Education Act, C.S.Nu., c. E-10, s. 4(2) (CanLII).

In October 2021, Nunavut Tunngavik Incorporated (NTI) launched a lawsuit in the Nunavut Court of Justice challenging the territorial government’s failure to provide Inuit language education as it had committed to do in 2008. At the time of updating this HillStudy, the case had still not been heard on the merits. See NTI, NTI v GN 2021: Equality Rights Claim about Inuit Language Education; Karine Lavoie, “Poursuite historique contre le gouvernement du Nunavut,” Francopresse, 12 November 2021 [in French]; NTI, NTI Welcomes Nunavut Court of Appeal Decision Allowing Inuktut Discrimination Lawsuit to Move Forward in Court, News release, 29 August 2024; and The Canadian Press, “Un pas de plus vers l’audition pour l’affaire de l’enseignement en langue inuite,” L’actualité, 29 May 2025 [in French].

[ Return to text ]In Quebec, recent amendments to the Charter of the French Language mean that a municipality whose representation of residents with English as a mother tongue falls below 50% will automatically lose its status as a bilingual municipality unless it adopts, within a prescribed period of time, a resolution requesting that it retain its bilingual status. In the spring of 2023, all the municipalities covered by this provision chose to retain their right to serve the public in English and French. See Quebec, Charter of the French Language, c. C‑11, ss. 29.1 and 29.2; and Morgan Lowrie, The Canadian Press, “All Quebec’s bilingual towns resolve to keep right to operate in English and French,” Winnipeg Free Press, 16 May 2023.

In Ontario, the French Language Services Act allows – but does not require – the adoption of a by-law providing that the administration of the municipality shall be conducted in both English and French. Some municipalities in the province have adopted by-laws to this effect. Since 2017, section 11.1 of the City of Ottawa Act, 1999 recognizes Ottawa’s bilingual character. See Ontario, French Language Services Act, R.S.O. 1990, c. F.32, s. 14; and Ontario, City of Ottawa Act, 1999, S.O. 1999, c. 14, Schedule E.

In New Brunswick, the Official Languages Act sets out requirements for municipalities whose official language minority population represents at least 20%. See New Brunswick, Official Languages Act ![]() (199 KB, 24 pages), S.N.B. 2002, c. O-0.5, s. 35.

(199 KB, 24 pages), S.N.B. 2002, c. O-0.5, s. 35.

In Manitoba, The Municipal Act sets out conditions that must be met to amend or repeal a French‑language services by-law. See Manitoba, The Municipal Act, C.C.S.M. 1996, c. M225, s. 147.1.

[ Return to text ]Ibid., ss. 3 and 8–10.

The Bilingual Service Centres Act already sets out the provision of services in French in regions where Manitoba’s francophone community has a high degree of vitality. See Manitoba, The Bilingual Service Centres Act, C.C.S.M. 2012, c. B37.

[ Return to text ]Ontario, Ontario Immigration Act, 2015, S.O. 2015, c. 8.

In other provinces and territories, most approaches to recognizing the role of minority communities in immigration are made through agreements between the federal and provincial or territorial governments, not through specific legislation or regulations. See Government of Canada, Federal–Provincial/Territorial Agreements.

[ Return to text ]© Library of Parliament