The purpose of the Official Languages Act (OLA) is to ensure respect for English and French as the official languages of Canada. Pursuant to the OLA and to regulations and current policies, federal institutions are guided by certain fundamental principles that help them ensure the equality of status and use of these two languages in their internal operations, among their employees and in their interactions with the public.

The OLA sets out the right of Canadians to communicate with and receive services from federal institutions in the official language of their choice. Year after year, services to the public generate the most complaints to the Commissioner of Official Languages. The number of these complaints has increased since 2014–2015. This increase is partly the result of federal institutions not being fully aware of their official languages responsibilities or not adequately considering them in every context, including the digital realm. Actively offering services in both official languages, providing the travelling public with bilingual services and ensuring third-party services delivered on behalf of federal institutions are bilingual are among the ongoing challenges.

In 2019, the federal government changed the criteria for offering services to the public in both official languages. It also revised its regulatory framework to ensure services to the public are consistent with the OLA. By 2027, more Canadians will be able to receive services from federal institutions in the official language of their choice. Moreover, in 2023, the OLA underwent substantial reforms to adapt it to today’s technological, sociodemographic and legal realities. These changes relate to some aspects of communications with and services to the public in English and French.

In addition, the OLA stipulates the right of employees of federal institutions to work in the official language of their choice. This right, which applies only in regions designated as bilingual for language-of-work purposes, has also been the subject of a growing number of complaints to the Commissioner of Official Languages since 2014–2015. Initiatives launched in 2017 show that a culture of linguistic duality in the workplace is not yet fully established. French remains underused in documents, meetings and interactions with supervisors. Steps were taken to increase managers’ responsibilities and improve oversight. Moreover, the legislative amendments of 2023 clarified some aspects of the right to work in English and French in federal institutions.

The OLA also sets out the government’s commitment to provide English- and French-speaking Canadians with equal opportunities for employment and advancement in federal institutions. Furthermore, it provides for language requirements in staffing processes. The number of complaints relating to this issue is slightly higher than in 2014–2015 following major fluctuations during the period, forcing the federal government to take steps to reverse the trend. However, the Commissioner of Official Languages has found that progress in this area is slow. In general, expectations for official languages management are high, and the legislative changes of 2023 have raised hopes for the years ahead.

Despite the progress made so far, the two official languages still do not have equal standing in the federal public service. Crises and emergencies such as the COVID-19 pandemic, the growing use of technology in the workplace and the emergence of artificial intelligence underscore the challenges federal institutions face in meeting their linguistic obligations. The modernization of the OLA was an opportunity to strengthen existing duties and clarify the responsibilities of key players. This HillStudy provides an overview of contemporary official languages issues and highlights those to watch in the years to come.

This HillStudy outlines the fundamental principles for ensuring respect for official languages in the federal public service, explains the responsibilities of key players in official languages matters and reviews some recently debated issues relating to the status of English and French in departments, agencies, bodies and Crown corporations subject to the Official Languages Act (OLA).1 It discusses the amendments made to the OLA by Bill C-13, An Act to amend the Official Languages Act, to enact the Use of French in Federally Regulated Private Businesses Act and to make related amendments to other Acts, which received Royal Assent on 20 June 2023.2

However, it does not discuss the new language regime that applies to the federally regulated private sector, which falls under a separate law, the Use of French in Federally Regulated Private Businesses Act.3 In addition, while the OLA now recognizes the importance of working to reclaim, revitalize and strengthen Indigenous languages, this HillStudy does not deal with recent efforts to foster recognition of the language rights of Indigenous federal employees.4

The OLA sets out three broad principles concerning respect for official languages in the federal public service:

Over the years, the federal government has implemented various policies to implement these principles in federal institutions.

The first principle is the right of the public to communicate with and be served by federal institutions in the official language of their choice. This right is enshrined in section 20 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms5 and in Part IV of the OLA. It is based on the notion that the government must adapt to meet the linguistic needs of the people, rather than the reverse. This is referred to as institutional bilingualism.

Not all offices of federal institutions are required to provide services in both official languages. Services are provided in both English and French where the use of these languages:

The Official Languages (Communications with and Services to the Public) Regulations (Official Languages Regulations)8 set out the criteria for determining which offices and service points must provide bilingual services. They include the following:

Offices and points of service that are subject to the Official Languages Regulations must actively provide their services in both official languages and inform the public of this by means of appropriate signage, a notice or other information. Communications with the public must occur through media that will reach members of the targeted linguistic clientele in an effective and efficient manner. The legislative amendments of 2023 specified that these duties apply to all forms of communication, publication and services provided, whether they are oral, written, electronic, virtual or other.

Every 10 years, the federal government reviews the application of the Official Languages Regulations to determine which offices must provide services in both official languages to meet the criterion of significant demand. The review is based on official languages data from the census and on the volume of services provided to the public. An Official Languages Regulations review is currently underway and is expected to conclude in 2027.10 This review is also taking into account the regulatory changes that were made in 2019 to provide a greater range of bilingual services to the Canadian public.11

Federal institutions are to take the following steps and comply with the Directive on the Implementation of the Official Languages (Communication with and Services to the Public) Regulations:12

Services provided to the public by videoconference are covered by the new Official Languages Regulations, a principle strengthened by the 2023 amendments to the OLA. As is the case for the recently amended OLA, the federal government will have to review these regulations and their administration and operation every 10 years and report to Parliament on the matter.17 According to Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (TBS) estimates, some 700 federal offices will likely be newly designated as bilingual because of these regulatory amendments.18

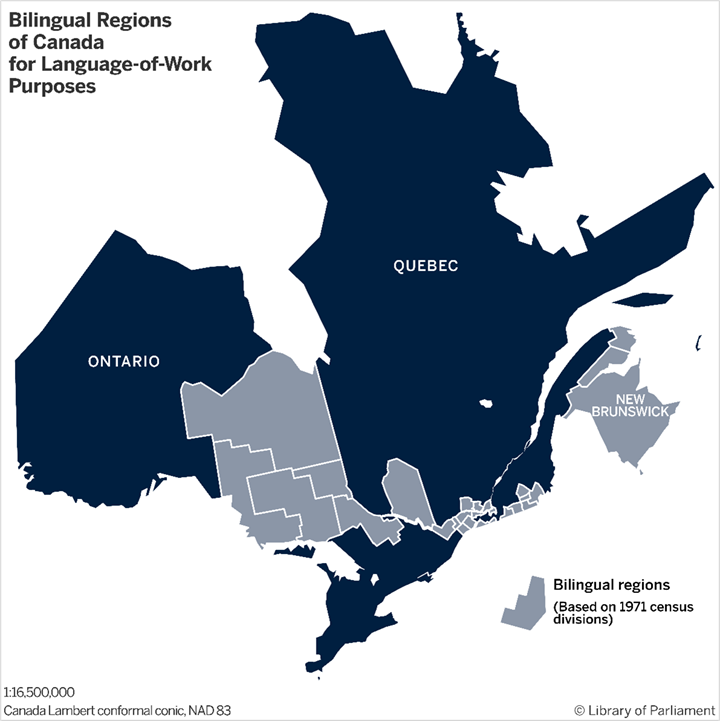

The second principle is the right of employees in federal institutions to work in the official language of their choice. This right is set out in Part V of the OLA. It applies to regions designated as bilingual, including the National Capital Region; some parts of northern and eastern Ontario; the region of Montréal and parts of the Eastern Townships, the Gaspé region and western Quebec; and New Brunswick, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 – Bilingual Regions of Canada for Language-of-Work Purposes, 1977 to Present

Sources: Map prepared by the Library of Parliament, 2023, using data obtained from University of Toronto Libraries, 1971 Census: Geospatial data and maps; and Government of Canada, List of Bilingual Regions of Canada for Language-of-Work Purposes. The following software was used: Esri, ArcGIS Pro, version 3.1.2. Contains information licensed under Open Government Licence – Canada and Statistics Canada Open Licence.

Federal institutions must foster an environment that is conducive to the use of both English and French as languages of work in regions that are designated as bilingual. This means that senior management must communicate effectively with employees in both official languages and must provide leadership in creating a bilingual work environment. The legislative amendments of 2023 clarified the responsibilities of managers and supervisors in this regard.

In addition, the use of both English and French must be encouraged in meetings. Public servants working in these regions have the right to use the official language of their choice to:

The federal public service designates a certain percentage of positions as bilingual by taking into account its obligations with respect to services to the public and to language of work. Where the provisions on language of work (Part V of the OLA) are incompatible with those on services to the public (Part IV of the OLA), the latter prevail.19 That said, bilingual employees working in bilingual-designated regions have the right to the workplace tools they need to provide high-quality services to the public in both official languages.20 Not all public service employees must be bilingual. The linguistic profile of bilingual positions is determined according to the duties and responsibilities of the position. Incumbents of a bilingual position who meet the requirements of their position based on the results of a second-language evaluation are eligible for the bilingualism bonus.21

Bilingual Positions and Employees

According to 2023 data, 41% of positions in the public service are designated as bilingual, while the percentage of bilingual employees is 38%. The greatest concentrations of bilingual positions are in the National Capital Region (62%), Quebec (67%) and New Brunswick (53%). In total, 95% of incumbents of bilingual positions meet the language requirements of their positions.

While the 2023 legislative amendments clarified the methods of communication, publication and services covered by the OLA, they did not specify whether the language-of-work duties apply to in-person, hybrid and virtual work. Since the COVID-19 pandemic began, the last two types of work have become commonplace in the federal public service.

No regulations set out the policies for giving effect to Part V of the OLA.

The third principle is the government’s commitment to provide equal opportunities for employment and advancement in federal institutions to both English- and French-speaking Canadians. This commitment is set out in Part VI of the OLA. The public service must reflect the presence of both the anglophone and francophone communities in the population as a whole. The public service employment rates for the two language groups vary with the mandate of the institution, the public served, the location of the offices and the categories of employment. According to the principle set out in section 39 of the OLA, federal institutions may not favour the employment of members of one language group over the other and must apply the merit principle when making staffing decisions.

Representation of Language Groups

Employment rates for both language groups in all institutions subject to the Official Languages Act have remained stable over time. In 2023, 75% of employees were anglophone, while 25% were francophone. According to 2021 Census data, English was the first official language spoken by 76% of Canadians, while French was the first official language spoken by 22% of Canadians. The remainder of the population could not conduct a conversation in either English or French.

No regulations set out the policies for giving effect to Part VI of the OLA.

The President of the Treasury Board applies and oversees the implementation of Parts IV, V and VI of the OLA. The President reports annually to Parliament on the performance of federal institutions in official languages matters.22 In 2023, the President’s responsibilities were reinforced and expanded. In addition to the power to ensure compliance with official languages requirements in the federal public service, the President is now responsible for establishing policies relating to the implementation of positive measures and agreements with the provincial and territorial governments (Part VII of the OLA). The President is also tasked with exercising leadership in implementing and coordinating the OLA and must assist the Minister of Canadian Heritage in carrying out the latter’s duties.

Over the years, the federal government has adopted a variety of policies and guidelines to apply the three principles set out in the OLA. The current official languages policy suite came into effect on November 2012.23 The review led to the adoption of the Policy on Official Languages and three directives to help the institutions concerned implement this policy:

All federal institutions are subject to the policy and its three directives, with the exception of the Senate, the House of Commons, the Library of Parliament, the Office of the Senate Ethics Officer, the Office of the Conflict of Interest and Ethics Commissioner, the Parliamentary Protective Service and the Office of the Parliamentary Budget Officer. 24

In 2021, the federal government committed to reviewing and instituting new policy instruments once new legislative measures were adopted.25 It also announced investments in partnerships to strengthen Part VII of the OLA, in order to help federal institutions meet their responsibilities under that part of the Act, as part of the respective responsibility of TBS and Canadian Heritage.26

Positions designated as bilingual must be staffed by people who meet the language requirements of those positions. Since March 2007, this requirement also applies to positions at the EX-02 to EX-05 levels. Since June 2023, the OLA requires that managers and supervisors be able to communicate with their employees in the language of the employees’ choice, regardless of the linguistic identification of the employees’ positions.27 In addition, while the OLA does not require deputy ministers and associate deputy ministers to know both official languages, it now requires them to receive language training upon their appointment.28

Exceptions may be made under the Public Service Official Languages Exclusion Approval Order,29 which states that the person agrees in writing:

Moreover, language training is viewed as a professional-development and career advancement opportunity available to all public service employees. In 2021, the federal government further committed to developing a new second-language training framework for the public service that is adapted to the characteristics and needs of learners.30 The Guidelines on Second Official Language Training were published in 2024.31

The Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer of TBS coordinates the Official Languages Program in federal institutions that are subject to Parts IV, V and VI of the OLA. In recent years, many official languages responsibilities (e.g., linguistic training and staffing) have been delegated to the deputy heads of federal institutions, but this delegation authority was repealed as part of the 2023 legislative amendments.32

For federal institutions, compliance with official languages requirements in the public service is assessed in various ways, including through the following:

Parts IV and V of the OLA may give rise to both complaints to the Commissioner of Official Languages and to legal recourse before the Federal Court. This is also true for section 91 of the OLA, which pertains to linguistic requirements in staffing. However, there is no legal recourse before the Federal Court under Part VI.

The latest update to the OLA was officially made when Bill C-13 received Royal Assent in 2023, marking the end of the many parliamentary debates on the subject since 2017.38 In reports presented in 2019, stakeholders had recommended changes to parts of the OLA dealing with the public service, and some of their proposals were adopted.39 Other proposals were made during the COVID-19 pandemic. A list of some of the major changes follows:

In an official languages reform proposal released in February 2021, the federal government also proposed regulatory and administrative changes.42 However, no new regulations governing compliance with official languages duties in the public service are expected to be made for now, except as regards Part VII and administrative monetary penalties.

Communications with and services to the public generate most of the complaints made to the Commissioner of Official Languages every year.43 Although progress has been made in this area, some problems persist, particularly with respect to active offer of service, services to the travelling public in both English and French and services provided by third parties on behalf of federal institutions. There are many reasons for this: the requirements of the OLA seem sometimes misunderstood, some federal institutions appear not to be committed to implementing the provisions of the OLA and others may lack planning in this regard or fail to monitor the impact of their actions. The more frequent use of new communications methods in the digital age has made the situation more complex and sparked increasing numbers of complaints.

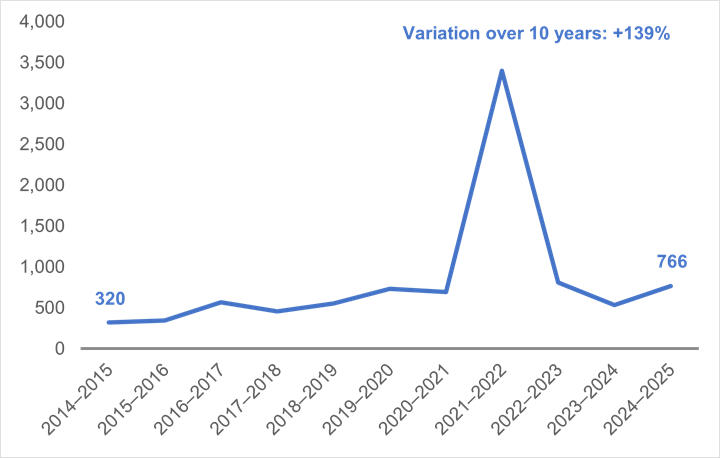

Since 2014–2015, when the number of complaints related to language of service was at its lowest, this number has more than doubled. It has varied somewhat over the last three years. After reaching its peak in 2021–2022, it dropped the next two years, then rose again in 2024–2025, as shown in Figure 2. In 2024–2025, 66% of complaints received by the Commissioner of Official Languages related to language of service.

Figure 2 – Services to the Public: Number of Admissible Complaints to the Commissioner of Official Languages, 2014–2015 to 2024–2025

Note: The high number of complaints received in 2021–2022 and 2022–2023 is in large part owing to a speech given by the Chief Executive Officer of Air Canada in English only and the complaints concerning traveller services.

Sources: Figure prepared by the Library of Parliament using data obtained from Office of the Commissioner of Official Languages (OCOL), Annual Report 2023–2024; and OCOL, Annual Report 2024–2025.

The 2009 Supreme Court of Canada decision in DesRochers v. Canada (Industry) highlighted the importance of offering services of equal quality in both official languages.44 Following this decision, TBS published an analytical grid to help federal institutions apply the principle of substantive equality to their programs and services.45 In 2019, in Thibodeau v. Air Canada, the Federal Court affirmed that the equality of official languages has four components: equality of status, equality of use, equality of access and equality of quality.46 The principle of substantive equality, whose application varied widely in the early 2010s, was included in the OLA with the 2023 amendments. It is one of the key principles for interpreting language rights.47

In-person active offer of service remains one of the weak links in the implementation of the OLA. This may be due to a lack of leadership, failure to communicate the importance of this obligation or the human element of front-line service. This is the area in which federal institutions show the poorest performance.48 The Commissioner of Official Languages found that active offer is inconsistent across federal institutions and that the situation is especially worrisome among federal institutions that provide services to the travelling public.49 Moreover, TBS called active offer an ongoing challenge in the implementation of the OLA, particularly in-person active offer.50

In July 2016, the Commissioner of Official Languages released a study on bilingual greetings in federal institutions, in which he described individual, organizational and social factors that influence whether an active offer of service in both official languages is made.51 He subsequently published a guide on active offer.52 The modernization of the OLA did not clarify this principle as some stakeholders had called for in 2019, but advances at the provincial level provide a renewed framework for interpreting active offer.53

Over the past decade, the provision of services to the travelling public has drawn the attention of the Commissioner of Official Languages, and it continues to pose challenges. Many complaints are made about this issue every year. The use of new technologies is no guarantee that services will be of equal quality in English and French, a fact that led the Commissioner to recommend new tools be developed to improve compliance with the OLA.54 The 2023 legislative amendments clarified language-related duties in this area, with the goal of:

In 2024, the Federal Court acknowledged that the Official Languages (Communications with and Services to the Public) Regulations must be given a liberal and generous interpretation, as does the OLA in the context of third-party contractor services offered to travellers.57

The inclusion of language clauses in agreements and contracts with third parties and the provision of services in both official languages on behalf of federal institutions have not always occurred and require constant effort by federal institutions.58 The 2023 legislative amendments clarified the language-related duties in this area in order to reflect a 2022 Federal Court of Appeal decision and to define a service provided on behalf of a federal institution.59

In September 2017, the Clerk of the Privy Council released a report on the state of bilingualism in the federal public service that included recommendations for improving the use of the two official languages in the workplace.60 The Committee of Assistant Deputy Ministers on Official Languages was mandated to follow up on the report. A dashboard indicates the implementation status of the short-term (2017–2019), medium-term (2020–2021) and long-term (post-2021) recommendations.61 TBS was tasked with implementing the recommendations regarding language training and the linguistic profile of supervisory positions.62

Commitments with regard to language of work have been slow to materialize. Several reports published by the Commissioner of Official Languages over the past 20 years have indicated that French remains underused and that the organizational culture of the federal public service is predominantly English. These reports also indicate that federal institutions have a poor track record for allowing employees to use their preferred official language with supervisors when drafting documents or during meetings. The TBS annual reports on official languages published between 2022 and 2024 confirmed this fact.63

The latest Public Service Employee Surveys and the 2021 Census data also confirm this trend.64 That said, since 2017, data on the use of official languages at work are no longer collected in a consistent way. This change led the Commissioner of Official Languages to recommend, in 2022–2023, improvements, after finding problems with measuring whether federal public servants can truly work in the official language of their choice.65

Moreover, federal public servants experience linguistic insecurity in the workplace, a persistent problem which has been amplified in the context of telework or hybrid work, and which forced TBS to create a working group to study the issue.66

In crises and emergencies, federal institutions find it even more difficult to meet their language of work obligations, which prompted the Commissioner of Official Languages to make recommendations to clarify the procedures to be followed in such circumstances.67 Since 2020, federal institutions have improved their performance, even though some of them still have difficulty incorporating official languages into their emergency planning and crisis management.68

During the COVID-19 pandemic, hybrid and virtual work became widespread in the federal public service. The Commissioner of Official Languages expressed concerns about disregard for federal public servants’ language rights.69 The 2023 legislative amendments did not specify that employees whose office is located in a bilingual-designated region retain their language rights if they work virtually from a region deemed unilingual for language-of-work purposes. Nor did the amendments adjust the concept of designated bilingual regions. The Commissioner had suggested broadening this concept, as did other stakeholders during the 2019 debate on modernizing the OLA. The intention was to make the duties in Parts IV and V of the OLA more consistent.70 In the fall of 2023, the Commissioner recommended that TBS issue clear and robust directives to federal institutions to guide the use of official languages in the context of telework and hybrid work.71

Improving employees’ language skills, strengthening official language capacity in federal institutions and showing clear and sustained leadership are some of the approaches put forward to ensure equitable treatment of both official languages in the workplace. A 2019 book that reviews the history of the implementation of official languages policy in the federal public service from the 1960s to the present confirmed that English remains dominant, in large part owing to managerial behaviour.72 The 2023 legislative amendments have raised hopes for improving the standing of French in the workplace.

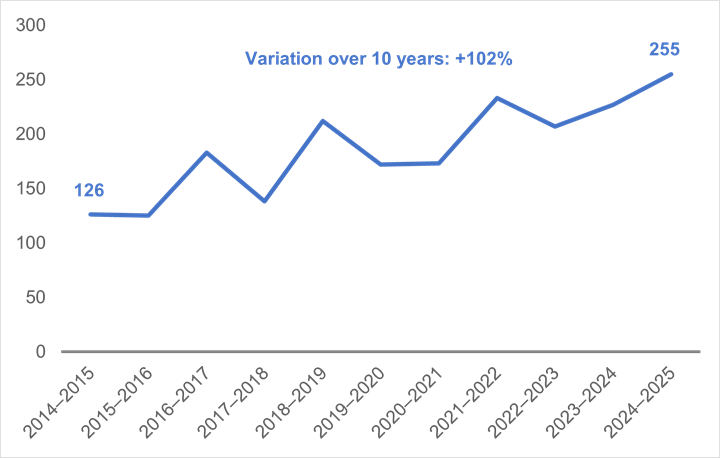

Between 2014–2015 and 2024–2025, the number of complaints regarding language of work doubled. This figure varied, rising and falling during that period as shown in Figure 3. In 2024–2025, complaints about language of work made up 22% of the complaints received by the Commissioner of Official Languages. That said, in June 2025, the Commissioner suggested that deficiencies in terms of language of work may have been underestimated.73

Figure 3 – Language of Work: Number of Admissible Complaints to the Commissioner of Official Languages (2014–2015 to 2024–2025)

Sources: Figure prepared by the Library of Parliament using data obtained from Office of the Commissioner of Official Languages (OCOL), Annual Report 2023–2024; and OCOL, Annual Report 2024–2025.

The federal government’s Action Plan for Official Languages, 2003–2008, proposed measures intended to create a public service that was exemplary in the area of official languages.74 The government’s objectives were to strengthen the bilingual capacity of federal public servants and to improve the quality of services offered in both languages. Furthermore, in the four government-wide strategies that followed – the Roadmap for Canada’s Linguistic Duality 2008–2013, the Roadmap for Canada’s Official Languages 2013–2018, the Action Plan for Official Languages 2018–2023 and the Action Plan for Official Languages 2023–2028 – the issue of respect for official languages in the public service received almost no attention.75

Over the years, many official languages responsibilities were delegated to the deputy heads of federal institutions. Concerns were raised about the governance structure in the public service, failures in managing of official languages and a lack of oversight. In his 2018–2019 annual report, the Commissioner of Official Languages argued that the following principles should underpin a new official languages governance structure:

The legislative amendments of 2023 were designed to address governance concerns and strengthen the Treasury Board’s implementation and oversight capacity for Parts IV, V and VI of the OLA. They also gave TBS new responsibilities for the implementation and general coordination of the OLA. In addition, the federal government committed to:

The Official Languages Accountability and Reporting Framework, which “must be read in conjunction with the [OLA], the applicable regulations and policy instruments,” was launched in June 2024.78 However, the Commissioner of Official Languages would have liked a more detailed framework and a clearer course of action.79

Managing official languages in federal institutions is challenging. Managers have difficulty objectively establishing the language requirements of positions for staffing actions. The Commissioner of Official Languages described the issue as systemic, prompting him to publish a report on problems related to implementing section 91 of the OLA and a guide for managers on the linguistic identification of positions, and to follow up on his recommendations.80

Managers must ensure that the linguistic profiles of positions reporting to them take into account obligations relating to service to the public and language of work. By underestimating the level of language proficiency required to fill these positions, they risk compromising:

Since the 2019–2020 fiscal year, TBS has been asking federal institutions to identify problems associated with implementing section 91 of the OLA in their official languages reviews.82 For his part, the Commissioner of Official Languages sends TBS quarterly reports on section 91 complaints.83 The Commissioner has recommended that TBS review its policies and tools, provide adequate training to managers and implement appropriate control and assessment mechanisms.84 In 2022–2023, the Commissioner lamented the lack of progress and recommended that the President of the Treasury Board implement an action plan to ensure federal institutions comply with section 91 of the OLA by June 2025.85 In a follow-up conducted in 2024, the Commissioner noted that most of his recommendations had been only partially implemented and that it was necessary for federal institutions to implement more official plans and mechanisms.86

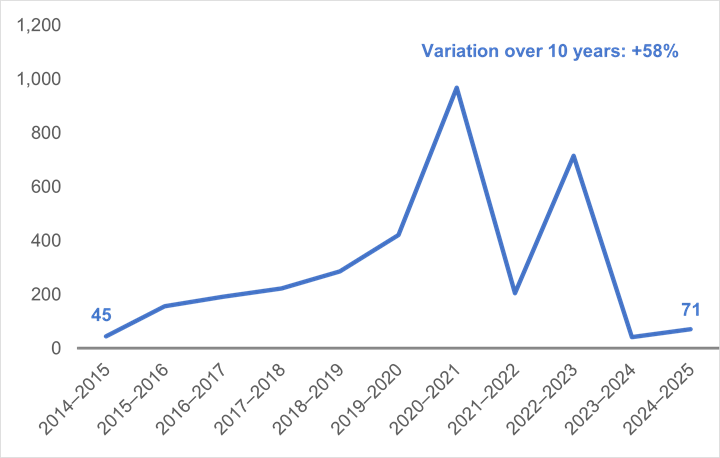

The number of complaints related to language requirements in staffing processes reached a new high in 2015–2016, with a total of 156 complaints received, and continued to grow until 2020–2021, then saw major fluctuations. In 2023–2024, the number of complaints about the language requirements of positions practically returned to its 2013–2014 level, then increased slightly in 2024–2025, as shown in Figure 4. Complaints relating to the language requirements of positions accounted for 6% of all complaints received by the Commissioner of Official Languages in 2024–2025. In his November 2020 report on implementing section 91 of the OLA, the Commissioner of Official Languages noted that founded complaints under section 91 of the OLA involved a significant number of federal institutions as well as positions in various groups and at various levels.87

Figure 4 – Language Requirements of Positions: Number of Admissible Complaints to the Commissioner of Official Languages, 2014–2015 to 2024–2025

Sources: Figure prepared by the Library of Parliament using data obtained from Office of the Commissioner of Official Languages (OCOL), Annual Report 2023–2024; and OCOL, Annual Report 2024–2025.

In 2013–2014, TBS and the Department of Canadian Heritage completed the first three-year data collection cycle for federal institutions concerning the implementation of Parts IV, V, VI and VII of the OLA. This three-year exercise, which started in 2011–2012, was completed in 2013–2014 and was performed every three years until 2022–2023, with the goal of improving coordination among federal institutions. Since 2023–2024, the targeted institutions must submit one or two reviews, every two years, on the achievement of certain OLA objectives in the form of a self evaluation of their performance.88 TBS uses these reviews to prepare its annual report on official languages.

In his annual report tabled in 2018, the Commissioner of Official Languages criticized the tools that TBS and the Department of Canadian Heritage were using and recommended changing them in order to gain a clearer picture of the status of the official languages across the federal public service.89 In June 2019, the Commissioner unveiled the Official Languages Maturity Model to help federal institutions better assess their performance in implementing the OLA.90 This model, structured to address three areas of activity, stopped being updated in 2022–2023 because of the amendments to the OLA, but will remain available to federal institutions that wish to use it.91

In the spring and fall of 2024, TBS held consultations on the use of artificial intelligence (AI) in the federal government, which led to the adoption, in March 2025, of the AI Strategy for the Federal Public Service.92 The Commissioner of Official Languages highlighted two issues:

A pilot project involving a self-service language centre has been launched across the federal public service, in collaboration with TBS and Public Services and Procurement Canada’s Translation Bureau, under the supervision of a new AI Centre of Expertise.94

In sum, the equality of status and use of English and French in federal institutions is not always fully ensured, despite being a requirement set out in the “Purpose” section of the OLA. Many are hopeful that the modernized legislative and regulatory frameworks and the coming updates to the policies and governance structure of the federal languages regime will increase conformity with the spirit and letter of the OLA. Many of the issues raised in this HillStudy will continue to garner attention over the years ahead, until the next review of the OLA and its regulations, expected by 2033.

In 2017, work began to remove the barriers Indigenous people face in the federal public service, leading to proposals to further their hiring, training and advancement. See Government of Canada, Many Voices One Mind: A Pathway to Reconciliation – Welcome, Respect, Support and Act to Fully Include Indigenous Peoples in the Federal Public Service, Final report of the Interdepartmental Circles on Indigenous Representation, 4 December 2017.

In its official languages reform proposal published in February 2021, the federal government briefly mentioned its commitment to take Indigenous languages into account in the federal public service, including in its future second-language training framework. See Government of Canada, English and French: Towards a substantive equality of official languages in Canada.

While Bill C-13 was being considered in Parliament, in 2022 and 2023, suggestions were made to improve the circumstances of Indigenous federal employees at the same time as the official languages regime of the federal public service was being enhanced. See Assembly of First Nations, Bill C-13, An Act to amend the Official Languages Act, to enact the Use of French in Federally Regulated Private Businesses Act and to make related amendments to other Acts ![]() (279 KB, 12 pages), Brief submitted to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Official Languages (LANG), 31 October 2022; First Nations Summit, Brief

(279 KB, 12 pages), Brief submitted to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Official Languages (LANG), 31 October 2022; First Nations Summit, Brief ![]() (507 KB, 10 pages) submitted to LANG; Senate, Standing Committee on Official Languages (OLLO), Third Report, 13 June 2023; Senate, Debates, 14 June 2023; and Senate, Debates, 15 June 2023.

(507 KB, 10 pages) submitted to LANG; Senate, Standing Committee on Official Languages (OLLO), Third Report, 13 June 2023; Senate, Debates, 14 June 2023; and Senate, Debates, 15 June 2023.

The new calculation method takes into account data on Canadians whose mother tongue is the minority language and Canadians who primarily or regularly speak that language at home. The federal government therefore abandoned the first-official-language-spoken estimation method from the former regulations, which did not reflect the use of the minority official language by immigrants, immersion students and bilingual families. See Government of Canada, Potential demand for federal communications and services in the minority official language (2021 Census data).

The vitality criterion in the new regulations accounts for the presence of a minority-official-language primary or secondary school in the service area of federal offices when determining whether they must provide communications with and services to the public in both official languages.

The list of key services subject to the general rules expands to include the Business Development Bank of Canada, the regional economic development agencies and all services provided by Service Canada centres and passport offices.

The 2021 Census data were published in 2022. Federal institutions had until 2024 to implement the new rules in effect.

[ Return to text ]Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (TBS), Annual Report on Official Languages 2018–19 ![]() (1.6 Mb, 71 pages), pp. 7–8; TBS, Annual Report on Official Languages 2019–20

(1.6 Mb, 71 pages), pp. 7–8; TBS, Annual Report on Official Languages 2019–20 ![]() (1.2 MB, 67 pages), p. 5; and TBS, Inclusive Official Languages Regulations: A New Approach to Serving Canadians in English and French

(1.2 MB, 67 pages), p. 5; and TBS, Inclusive Official Languages Regulations: A New Approach to Serving Canadians in English and French ![]() (1.9 MB, 39 pages), 4 May 2020.

(1.9 MB, 39 pages), 4 May 2020.

At the end of the process, the Burolis database will indicate whether each federal institution has a duty to communicate with and provide services to the public in both official languages. See Government of Canada, Burolis.

In his annual report of June 2025, the Commissioner of Official Languages indicates that he anticipates difficulties with the recruitment of bilingual employees and with the budgets allocated to language training. See OCOL, Annual Report 2024–2025 ![]() (1.90 MB, 31 pages), p. 11.

(1.90 MB, 31 pages), p. 11.

Official Languages Act, R.S.C. 1985, c. 31 (4th Supp.), s. 31.

The Federal Court of Canada confirmed this principle on 30 October 2015. See Tailleur v. Canada (Attorney General), 2015 FC 1230.

[ Return to text ]Government of Canada, English and French: Towards a substantive equality of official languages in Canada.

Over the years, responsibility for language training was transferred to the deputy heads of federal institutions. Gaps in the delivery of language training services and accountability for these services were found. Since 1999, data on federal institutions’ provision of language training have not been collected consistently. A 2018 report and a 2023 article found that the quality and calibre of language training have fallen. See National Joint Council, OL Committee Report on the State of Bilingualism in the Public Service, 4 September 2018; and Lila Mouch-Essers, “Le français dans la fonction publique : un apprentissage au rabais,” ONFR TFO, 15 May 2023.

[ Return to text ]Thibodeau v. St. John’s International Airport Authority, 2022 FC 563; and Official Languages Act, R.S.C. 1985, c. 31 (4th Supp.), s. 23(1).

In November 2024, the Federal Court of Appeal, in a majority decision, upheld the trial judge’s decision. However, in January 2025, the airport authority requested leave to appeal the decision to the Supreme Court of Canada. See St. John’s International Airport Authority v. Thibodeau, 2024 FCA 197; OCOL, Annual Report 2024–2025 ![]() (1.90 MB, 31 pages), p. 9; and Supreme Court of Canada, Case no. 41651.

(1.90 MB, 31 pages), p. 9; and Supreme Court of Canada, Case no. 41651.

© Library of Parliament