In the Canadian parliamentary context, English and French enjoy equality of status and use. In fact, there are a number of constitutional and legislative provisions governing the use of both official languages in Parliament. These provisions, which have evolved over the course of history, now apply to both the legislative process and parliamentary procedure and reflect the importance of the language rights granted to parliamentarians, as well as the people they serve.

The Constitution Act, 1867 introduced the first official languages guarantees and obligations for parliamentary institutions. Practices promoting legislative bilingualism have been developed over time, and parliamentary institutions have adapted accordingly, for example, by implementing simultaneous interpretation and adhering to the principle of co-drafting federal legislation. Certain practices were codified when the federal government adopted its very first Official Languages Act (OLA) in 1969.

Recognizing that bilingualism is an important feature of parliamentary democracy in Canada, the 1982 Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms codified language rights for parliamentary proceedings and documents. Canadian courts then clarified the scope of these rights and ordered Parliament to continue adapting its practices. In 1988, the language requirements regarding debates, proceedings, the legislative process and various parliamentary documents were set out in a new version of the OLA.

Parliamentary procedure has undergone several changes to provide a framework for the use of not only the official languages, but other ones too. In recent years, the Senate and the House of Commons have taken measures governing the use of Indigenous languages.

In addition, more resources were allocated for parliamentary translation and simultaneous interpretation to meet parliamentarians’ significant official language needs.

As well, bilingualism was added as a condition for the appointment of officers of Parliament.

Recent official languages challenges stemming from the use of new technologies, hybrid and virtual sittings and meetings, and artificial intelligence have appeared and required the Canadian Parliament to adapt its practices once again.

By promoting official language best practices, Parliament serves as a model of an institution that is accessible to English- and French-speaking Canadians.

In Canada, a number of constitutional and statutory provisions concern the use of official languages in the legislative realm, thus recognizing the right of both official language communities to participate equally in the parliamentary process. These provisions stem from the collective history of Canadians, and their presence in the Constitution of Canada confirms the fundamental nature of those rights.

This paper provides an overview of the various aspects of the issue of official languages in the context of the Canadian Parliament by examining

In the negotiations preceding Confederation in 1867, one of the proposed approaches was “optional” bilingualism in the activities of the future Parliament of Canada. French-Canadian members vigorously opposed this option, and their protests culminated in the passage of a resolution providing for the “mandatory” use of English and French in certain specific areas of parliamentary activity.1 That resolution became section 133 of the Constitution Act, 1867, which reads as follows:

Either the English or the French Language may be used by any Person in the Debates of the Houses of the Parliament of Canada and of the Houses of the Legislature of Quebec; and both those Languages shall be used in the respective Records and Journals of those Houses; and either of those Languages may be used by any Person or in any Pleading or Process in or issuing from any Court of Canada established under this Act, and in or from all or any of the Courts of Quebec.

The Acts of the Parliament of Canada and of the Legislature of Quebec shall be printed and published in both those Languages.2

The purpose of section 133 is to grant “equal access for anglophones and francophones to the law in their language” and to guarantee “equal participation in the debates and proceedings of Parliament.”3 Interpretation of section 133 must take that purpose into account. Without granting English and French official status, section 133 nevertheless confirms the bilingual character of the Parliament of Canada, which Senator Gérald A. Beaudoin has called the “embryo of official bilingualism.”4 Section 133 of the Constitution Act, 1867 has been interpreted by the Supreme Court of Canada on various occasions, thus elucidating its scope. The following sections look at each of the components of section 133.

Section 133 of the Constitution Act, 1867

This provision sets out three types of legislative guarantees:

Section 133 expressly guarantees all parliamentarians the right to use English or French in parliamentary debates. As not all parliamentarians are bilingual, a system of simultaneous interpretation was introduced in the House of Commons in 1959 as a result of a motion by Prime Minister John Diefenbaker,5 thus enabling all members to express themselves in the official language of their choice and to be understood by all members of the House. Before that system was introduced, a parliamentarian speaking French was generally not understood by the anglophone majority, which had the effect of emptying the House of Commons of a large number of its members.6 In the Senate, simultaneous interpretation was introduced in 1961.7

When the interpretation system was established, a small group of seven interpreters assumed responsibility for interpreting all debates.8 Since then, the Translation Bureau’s Services to Parliament and Interpretation Sector has expanded to some 60 permanent interpreters in addition to freelance interpreters.9

In accordance with a decision rendered by the Supreme Court of Canada in 1986 (MacDonald v. City of Montreal), it is still unclear whether the right to use English or French in parliamentary debates also includes the constitutional right to simultaneous interpretation.10 In an incidental statement in the decision, Justice Jean Beetz said that the right to use English or French in parliamentary debates did not include the right to simultaneous interpretation. It is useful to note that the MacDonald decision is part of a case law trend advocating the restrictive interpretation of language rights, a trend overruled by the 1999 decision in R. v. Beaulac,11 in which the Supreme Court of Canada redefined the rules for interpreting language rights. Section 133, and language rights in general, must now be given a broad and liberal interpretation based on their objectives.

In addition, it is apparent from Prime Minister Diefenbaker’s remarks when the motion on the simultaneous interpretation system was passed that the system’s introduction was clearly viewed as the recognition of a constitutional right:

I also believe this motion will provide belated recognition of the fact that under our constitution this basic right has been secured and will be maintained as part of our constitutional freedom, and will be regarded as unchangeable and unchanging. This view, I believe, is of the essence in the maintenance of unity within our country. After all, our very confederation came about as a consequence of the partnership between those of French and English origin. Because of that fact[,] everything we can do to ensure the preservation of those basic constitutional rights and the equality of those rights of language should be attained and implemented.12

Given the importance of ensuring respect for every person’s right to use the official language of their choice and to be understood within an appropriate period of time, this practice, whether or not it enjoys constitutional protection, is now essential to the proper operation of Parliament.

Section 133 provides that “records and journals” must be prepared in both official languages. This obligation of bilingualism presupposes the simultaneous use of English and French in the publication of those parliamentary documents: “Both languages, and not one or the other, must be used in the records and journals.”13 It is not enough to produce certain passages in English and others in French or to summarize them in the other official language. Documents must be made available in full, simultaneously, in both official languages.

What documents are subject to this obligation? First, the “records” of the houses, which include their Acts and bills.14 Second, the “journals,” which are the Minutes of Proceedings and Journals – the official minutes of the votes and proceedings of the houses. Before 1976, the Journals were printed in separate English and French versions. Since the 2nd Session of the 30th Parliament, they have been published in a two-column bilingual format.15

Section 133 expressly provides that the Acts of Canada shall be printed and published in English and French. This is called legislative bilingualism.16

As the text of section 133 is not explicit on whether the obligation of bilingualism applies to the entire legislative process, we must turn to the interpretation made by the courts in order to determine the scope of the provision. In Blaikie v. Québec (Attorney General) (1978), Chief Justice Jules Deschênes of the Superior Court of Quebec, whose findings were confirmed by the Supreme Court of Canada in 1985,17 held that the obligation to print and publish Acts in English and French necessarily included the obligation to use English and French simultaneously throughout the legislative process:

Now if the reasoning appears naïve, it remains none the less unassailable: how to print and publish in the two languages a law which has not been adopted and does only officially exist in one of the languages?18

Thus, for the English and French versions of Acts to be equally authoritative, they must be passed and assented to in both languages. Simply printing and publishing them in both languages is not sufficient to respect either the letter or the spirit of section 133.19 Since 1978, federal legislation has been co-drafted by pairs of law clerks, one anglophone and the other francophone, working together with the help of jurilinguists responsible for ensuring that the two versions match.20

Co-drafting

Federal legislative texts are prepared using a process called co-drafting. This means that the English and French versions of federal legislation are drafted simultaneously and neither is considered a translation of the other.

Section 133 concerns Acts, but it also covers delegated legislation. In its 1981 decision in Attorney General of Quebec v. Blaikie et al., the Supreme Court of Canada held that the obligation of bilingualism applied to regulatory enactments issued by the government, by a minister or by a group of ministers. Regulations made by the executive branch are similar to government measures and are thus subject to the obligation of bilingualism provided for in section 133.21

As for orders in council, the Supreme Court of Canada held in Reference re Manitoba Language Rights (1992) that the obligation of bilingualism also covers instruments of a “legislative nature.”22 To determine whether an order in council is of a legislative nature, the Court held that the form, content and effect of the instrument in question must be considered. These criteria do not operate cumulatively.23 As regards form, the connection between the legislative instrument and the legislature must be examined. With respect to content, it must be determined whether the instrument embodies a rule of conduct. Lastly, as to effect, it must be determined whether the instrument has the force of law and whether it applies to an undetermined number of persons.

The Supreme Court of Canada also considered the issue of the application of the bilingualism rule in the case of documents incorporated by reference. In the context of section 23 of the Manitoba Act, it established the test that must be applied:

Some documents are simply mentioned in legislative instruments; they need not be consulted before the operation of the instrument in question can be understood. Others are “incorporated by reference” in the sense that they are an integral part of the primary instrument as if reproduced therein. It is this latter type of incorporation that can be termed “true incorporation” and that potentially attracts translation obligations under s. 23.24 [AUTHOR’S EMPHASIS]

Thus, instruments that are an integral part of the Act or regulations must be available in both official languages. In 2017 and 2018, the Standing Joint Committee for the Scrutiny of Regulations reiterated that documents incorporated by reference in federal regulations must be available in both official languages to be considered accessible in accordance with the Statutory Instruments Act.25 In practice, there are exceptions. According to a federal government policy that came into effect in September 2018, federal departments may incorporate unilingual material by reference “when there is a legitimate reason to do so.”26

With regard to the provisions concerning Parliament, the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms (the Charter),27 which was adopted in 1982, essentially restates the same rights and obligations as section 133, but with a few additions and clarifications.

First of all, the first subsection of section 16 of the Charter enshrines in the Constitution the status of English and French as the official languages of Canada. Official language status had been granted to English and French in the OLA (1969),28 but that principle was not constitutionally protected.

For the purposes of this paper, it is also important to mention sections 17 and 18 of the Charter, which concern, respectively, the language of the debates and proceedings of Parliament and the language of Acts and other parliamentary instruments. More specifically, section 17 provides that “[e]veryone has the right to use English or French in any debates and other proceedings of Parliament.” This provision essentially confirms an established fact by reasserting the right to use the official language of one’s choice in debates in the houses of Parliament, a right already guaranteed by section 133 of the Constitution Act, 1867.

Section 17 of the Charter nevertheless adds a new element, in that it extends that right to other parliamentary proceedings, such as those of committees of the Senate and the House of Commons. The right to use the official language of one’s choice before the Senate or House of Commons and committees of Parliament is thus a constitutional right.

Section 18 of the Charter provides that “[t]he statutes, records and journals of Parliament shall be printed and published in English and French and both language versions are equally authoritative.” These rights and obligations, already provided by section 133 of the Constitution Act, 1867, suggest that Acts are passed in both official languages. With its inclusion in the Charter, this principle, which had not been expressly stated in section 133, is now recognized in the Constitution of Canada.29 The courts strive to interpret bilingual legislation using the equal authenticity rule, which requires reading versions in both languages and considering them to equally have the force of law, with neither version taking precedence over the other.30

Equal Authenticity Rule and Shared-Meaning Rule

The English and French versions of federal legislation both have the force of law and are equally authoritative, and neither version takes precedence over the other. The courts interpret legislation using the equal authenticity rule. In the event of a discrepancy, the courts must determine the meaning common to both versions.

The equal authenticity rule applies to bilingual laws and constitutional documents alike. Provisions were added in this respect to Part VII of the Constitution Act, 198231 in order to

An official French version of the constitutional documents included in the schedule to the Constitution Act, 1982 has yet to be adopted.33 In 1990, the French Constitutional Drafting Committee presented a report to implement the provisions of section 55.34 However, neither Parliament nor the provincial and territorial legislative assemblies have endorsed it. This issue was raised a number of times in recent years, including during

The constitutional guarantees provide a minimum level of protection for official languages; this protection is supplemented by federal and provincial statutes.39 In 1969, Parliament passed the first OLA following the recommendations of the Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism. The Act recognized, for the first time, the official language status of English and French in all matters pertaining to Parliament and the Government of Canada.

Following adoption of the Charter, a new OLA40 was passed in 1988 to take into account the new constitutional guarantees regarding language rights.

The first two parts of the OLA are particularly relevant to this paper. Part I involves the language of the debates and proceedings of Parliament; Part II addresses the language of legislative and other instruments of a parliamentary nature. Incidentally, it is also important to note that the provisions concerning the institutions of Parliament do not appear solely in the first two parts of the OLA. The Senate, the House of Commons, the Library of Parliament, the Office of the Senate Ethics Officer, the Office of the Conflict of Interest and Ethics Commissioner, the Parliamentary Protective Service and the Office of the Parliamentary Budget Officer are the “institutions” enumerated in section 3 of the OLA and, consequently, are subject to other parts of the Act involving, in particular, language of work and language of services offered to the public.

The courts have given quasi-constitutional status to the OLA. In Lavigne v. Canada (Office of the Commissioner of Official Languages) (2002), the Supreme Court of Canada confirmed that the OLA is no ordinary statute:

The importance of these objectives and of the constitutional values embodied in the Official Languages Act gives the latter a special status in the Canadian legal framework. Its quasi-constitutional status has been recognized by the Canadian courts.

... The constitutional roots of that Act, and its crucial role in relation to bilingualism, justify that interpretation.41

In 2014, in Thibodeau v. Air Canada, the Supreme Court of Canada reaffirmed the quasi-constitutional status of the OLA, repeating that “it belongs to that privileged category of legislation which reflects ‘certain basic goals of our society’ and must be so interpreted ‘as to advance the broad policy considerations underlying it.’”42

The OLA contains provisions that derive from various constitutional provisions, but, with regard to parliamentary debates and legislative enactments, these provisions often go beyond the constitutional guarantees examined above.

Part I of the OLA consists of a single section on the language of the debates and proceedings of Parliament. Its first subsection confirms that English and French are the official languages of Parliament, and that everyone has the right to use either of those languages in any debates and other proceedings of Parliament. This first subsection essentially restates the rights guaranteed by section 133 of the Constitution Act, 1867 and section 17 of the Charter. The second subsection goes beyond existing constitutional provisions by guaranteeing the right to simultaneous interpretation of the debates and other proceedings of Parliament.

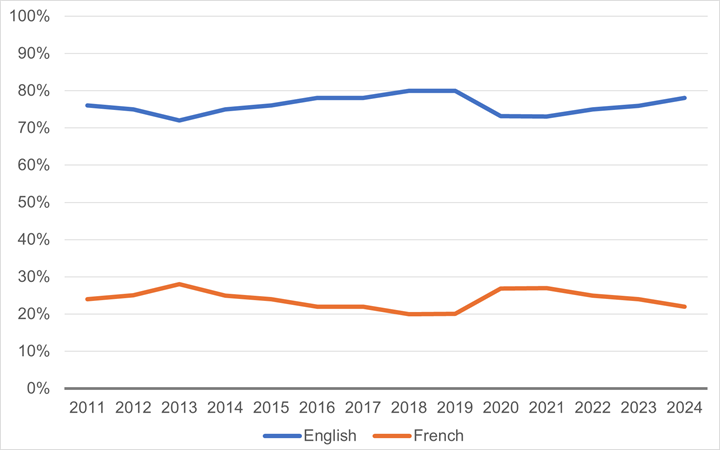

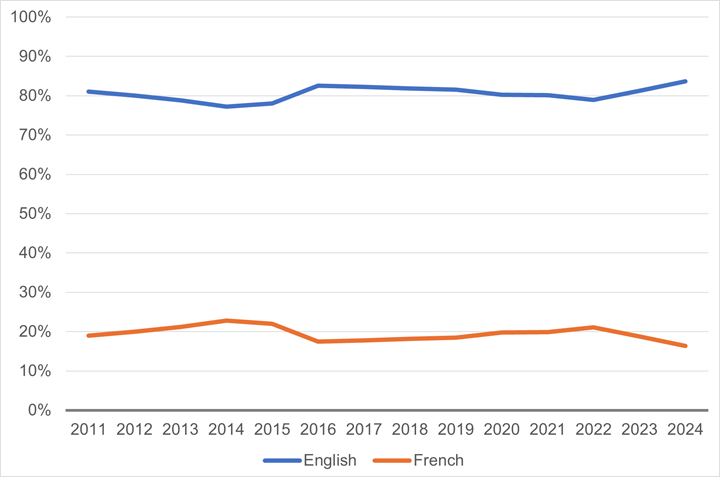

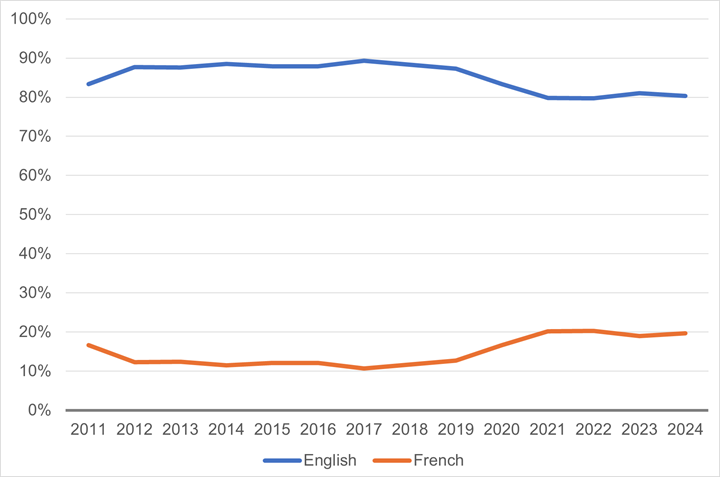

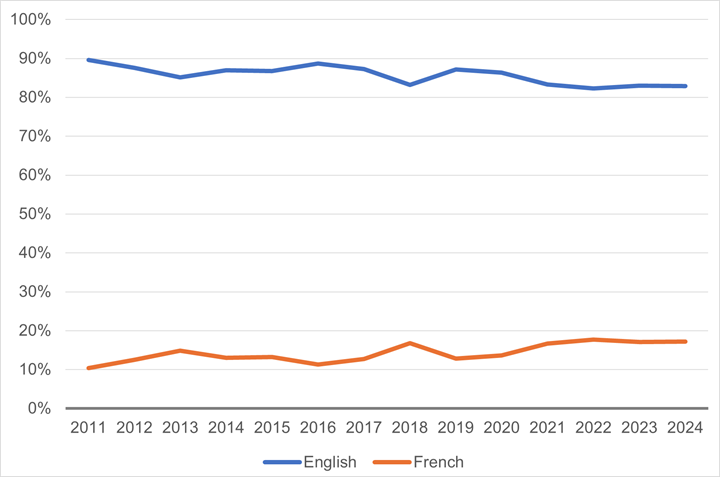

The following figures show the proportion of English and French used by members of Parliament (MPs) in the House of Commons (see Figure 1), by senators in the Senate (see Figure 2), by MPs in committee (see Figure 3) and by senators in committee (see Figure 4) over the past 14 years. In 2024, French was used 22% of the time in the House of Commons, 16% of the time in the Senate, 20% of the time by MPs in committee and 17% of the time by senators in committee. French is used less often in committee, by both MPs and senators, with an average of between 14% and 15% of all statements during this period.43

Figure 1 – Use of English and French by Members of Parliament in the House of Commons, 2011–2024

Note: Data are compiled by year and do not take into account the use of languages other than English and French.

Source: Figure prepared by the Library of Parliament from data provided by the House of Commons Parliamentary Publications Directorate, accessed 7 July 2025.

Figure 2 – Use of English and French by Senators in the Senate, 2011–2024

Note: Data are compiled by year and do not take into account the use of languages other than English and French.

Source: Figure prepared by the Library of Parliament from data provided by the Senate Communications, Broadcasting and Publications Directorate, accessed 13 June 2025.

Figure 3 – Use of English and French by Members of Parliament in Committee, 2011–2024

Note: Data are compiled by year and do not take into account the use of languages other than English and French.

Source: Figure prepared by the Library of Parliament using data obtained the House of Commons Parliamentary Publications Directorate, accessed 7 July 2025.

Figure 4 – Use of English and French by Senators in Committee, 2011–2024

Note: Data are compiled by year and do not take into account the use of languages other than English and French.

Source: Figure prepared by the Library of Parliament from data provided by the Senate Communications, Broadcasting and Publications Directorate, accessed 13 June 2025.

While knowledge of both official languages is not required to serve as a parliamentarian, the two chambers have taken steps to promote parliamentarians’ personal bilingualism. Moreover, the appointment process in the Senate, introduced in 2016, provides that fluency in both official languages is “considered an asset”44 in Senate appointments. In the House of Commons, second-language courses are provided to parliamentarians, their spouses and House of Commons administration staff.45 Over the years, interest in language training has grown, particularly among ministers, parliamentary secretaries and members of shadow cabinets.46

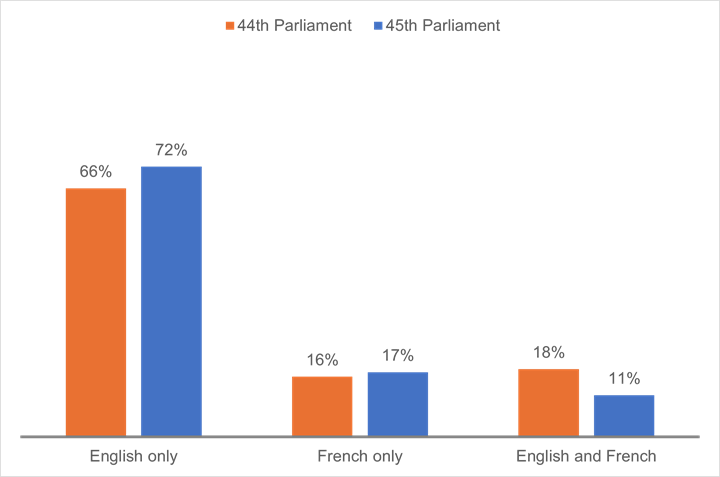

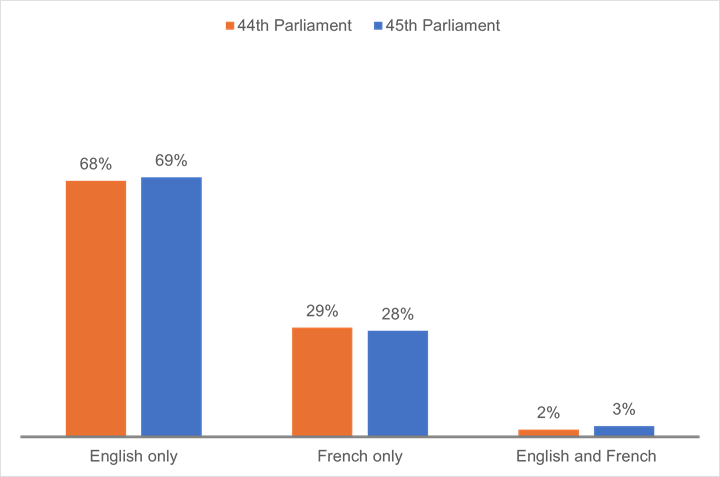

When they enter Parliament, parliamentarians are asked to state their preferred official language. The figures below show the preferred language of MPs (see Figure 5) and senators (see Figure 6) on a percentage basis for the 44th Parliament and 45th Parliament. At the beginning of the 44th Parliament, approximately 66% of MPs said that English was their preferred official language, and this figure rose to 72% at the start of the 45th Parliament. Approximately 16% of MPs in the 44th Parliament said that French was their preferred official language, and this figure remained roughly the same in the subsequent Parliament (17%). The percentage of MPs who had no preference fell from 18% to 11% from one Parliament to the next. In the Senate, 68% of sitting senators at the start of the 44th Parliament said that English was their preferred official language, 29% said that French was their preferred official language and 2% had no preference. These figures stayed about the same for sitting senators at the opening of the 45th Parliament: 69% preferred English, 28% preferred French and 3% had no preference for one or the other.

Figure 5 – Preferred Language of Members of Parliament, 44th Parliament and 45th Parliament

Source: Figure prepared by the Library of Parliament using data obtained from Library of Parliament, “Parliamentarians,” Parlinfo, Database, accessed 7 October 2025.

Figure 6 – Preferred Language of Senators, 44th Parliament and 45th Parliament

Source: Figure prepared by the Library of Parliament using data obtained from Library of Parliament, “Parliamentarians,” Parlinfo, Database, accessed 7 October 2025.

The broadcasting of the debates and proceedings of Parliament constitutes a service within the meaning of Part IV – Communications with and Services to the Public – of the OLA.47 Starting in 1977, the general public has been able to follow the debates of the House of Commons on radio and television. From 1979 to 1991, debates were broadcast by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) through two parliamentary channels, one English and the other French.48 The public was thus able to follow the debates in the official language of their choice.

In 1991, these parliamentary channels became a thing of the past as a result of budget cuts at the CBC. Since then, the Cable Public Affairs Channel (CPAC) has broadcast parliamentary debates and proceedings. The House transmits the English, French and original audio feeds to CPAC, which redistributes them to cable companies.

The agreement between the House of Commons and CPAC provided that the latter would distribute all feeds to the cable companies. However, the cable companies, which were not bound by that agreement with the House, could choose to broadcast only one of the three audio feeds. As a result, in some regions of the country, parliamentary debates were broadcast in only one official language or from the floor, that is the original feed without interpretation.

That situation resulted in a complaint filed under the OLA to the Office of the Commissioner of Official Languages, and then an application for remedy before the Federal Court of Canada. In its 2002 decision in Quigley v. Canada (House of Commons), the Court held that the House of Commons “must, if it uses another person or organization to deliver services that are required to be provided in both official languages, ensure that the person or organization providing such service does so in both official languages.”49 The House must therefore ensure that CPAC and, ultimately, cable companies, broadcast the debates in both official languages.

Since that time, the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission has required cable companies to broadcast the feeds in both official languages to ensure that parliamentary debates and proceedings are accessible to the public in the official language of their choice.50 Broadcasting obligations extend to Senate and House of Commons committee proceedings, when the feed is provided to CPAC.51 Depending on the region, the feed is available either on a separate channel or through second audio program (SAP) technology.52

In 2004, as a result of the work of the Special Committee on the Modernization and Improvement of the Procedures of the House of Commons, the ParlVU service53 was made available to the public on the parliamentary website, providing online access to House and committee proceedings in English, French and the language spoken during the proceedings, known as “floor sound.”54 The service is also available for Senate proceedings and its committees.55

In 2016, as part of the work of the Special Senate Committee on Senate Modernization, a report was tabled requesting that

Senate proceedings have been broadcast on CPAC since March 2019.57

In budget 2017, the federal government made a commitment with respect to official languages in the parliamentary context.58 In budget 2021 and budget 2024, the federal government made further commitments to support parliamentary translation and interpretation services.59 In fall 2025, the quality of the interpretation provided to Parliament received attention.60

In March 2018, the Advisory Working Group on the Parliamentary Translation Services of the Senate Standing Committee on Internal Economy, Budgets and Administration presented a report to the Senate that included recommendations to improve translation and interpretation services in the Senate.61 The government presented its response seven months later, in which it described the measures taken by the Translation Bureau to improve the quality of services provided to the Senate.62 Since then, the Translation Bureau has appeared annually before that Senate committee to provide an update on its services to the Senate. In addition, in 2022, the Senate and Public Services and Procurement Canada entered into a five-year partnership for the provision of linguistic services to senators.

The Library of Parliament’s Canadian Parliamentary Historical Resources online portal provides public access to the historical debates and journals of the Senate and the House of Commons, as well as their respective committees’ evidence, in both official languages.63

In 1871 and in 1880 respectively, the Senate and the House of Commons adopted official reporting of their debates, issuing them in bound, indexed volumes. These debates, which have been digitized, are available on the portal. Reconstituted debates – debates that were held prior to the adoption of official reporting – are also available on the portal, although they are unofficial versions. While some debates were initially published in only one official language, the portal offers translated versions for most parliaments.

Part II of the OLA concerns legislation and other instruments of a parliamentary nature. Among other things, this part contains provisions relating to the archiving, printing and publication of the records and journals of Parliament (section 5), as well as a provision on the enactment, printing and publishing of the Acts of Parliament (section 6).

These provisions reproduce the constitutional obligations examined above, but the OLA expressly states that it applies to the legislation enactment process, which therefore must be carried out in both official languages.

The OLA also addresses the issue of delegated legislation and all instruments published in the Canada Gazette, as well as instruments of a public and general nature (section 7(1)). The OLA thus goes beyond the tests established by the Supreme Court of Canada in Blaikie (1981) and Reference re Manitoba Language Rights (1992) by requiring that everything published in the Canada Gazette appear in both official languages. Section 7(2) concerns instruments made under executive power. Such instruments must also be published in both official languages if they are of a public and general nature.

Section 13 restates a constitutional principle, and, by doing so, highlights an important principle of legislative interpretation: the English and French versions of legislative Acts covered by Part II are equally authoritative.

Parliamentary institutions are also subject to the other provisions of the OLA. They have developed, however, official language policies and guidelines that are different from those used in the rest of the federal public service. Parliamentary institutions are required to deliver public services and communications in an individual’s preferred official language and can be sanctioned by the courts should they fail to comply. In a fall 2019 decision, the Federal Court ruled that the Senate had failed to meet its language obligations in terms of signage and reiterated the important symbolic role played by parliamentary institutions with regard to respecting Canada’s two official languages:

It bears reminding that the House of Commons and the Senate are not only subject to the OLA but also embody the constitutional and quasi-constitutional values recognized in the Charter and the OLA, including, of course, institutional bilingualism.

... The relics of the past that express the preponderance of the use of one official language to the detriment of the other in an institutionalized context have no place in the buildings of Parliament and the Government of Canada. This is the case of the unilingual drinking fountains in the Senate, which have become, over time and with the passing years, conspicuously obsolete objects, incompatible with the constitutional principle of the protection of minorities.64

The Senate decided not to appeal this decision.

Multiple reports and briefs advocating for a modernization of the OLA were published in 2019, the 50th anniversary of the adoption of the first Act. Although there have been calls to amend parts I and II of the OLA, they have only represented a small part of the larger debate. Some of the propositions include

In her mandate letter, published on 13 December 2019, the Honourable Mélanie Joly, then Minister of Economic Development and Official Languages, was given the mandate to modernize the OLA.66 In her supplementary mandate letter of 15 January 2021, she was asked to introduce legislation to this effect and recognize the unique reality of French.67

On 15 June 2021, she introduced Bill C-32.68 The bill, which died on the Order Paper when Parliament was dissolved in August that same year, did not provide for any substantive changes to the language obligations of Parliament. That said, it proposed to recognize, in the preamble to the OLA, the diversity of the provincial and territorial language regimes, particularly the constitutional provisions applicable to Quebec, Manitoba and New Brunswick with respect to legislative bilingualism.69

In March 2022, the government introduced Bill C-13, which did not include any other changes to the provisions on official languages in Parliament.70 Bill C-13 received Royal Assent in June 2023. In response to the modernized OLA, the Standing Senate Committee on Official Languages made a general observation to the federal government encouraging it to strengthen the role of the Translation Bureau’s translation and interpretation functions.71

Canada’s linguistic duality is apparent not only in the Constitution and legislation, but also in the procedures and practices of the Senate and the House of Commons. For example, the first bilingual Speaker of the House of Commons, Joseph Godéric Blanchet,72 used to alternate between English and French versions of the prayer recited at the start of each sitting.73

Standing Order 7(2) of the Standing Orders of the House of Commons provides that the member elected to serve as Deputy Speaker of the House shall be required “to possess the full and practical knowledge of the official language which is not that of the Speaker.”74 For example, when Jeanne Sauvé, who was of Franco Saskatchewanian origin, was Speaker of the House of Commons in the early 1980s, the Deputy Speaker was Lloyd Francis, an anglophone from the Ottawa region. However, this Standing Order has not been followed since the beginning of the 37th Parliament in January 2001. Wherever possible, bilingual candidates are to be sought for this position.75

Three other provisions of the Standing Orders of the House of Commons contain procedural language requirements:

Linguistic duality is also evident in the context of parliamentary committees. At the start of each parliamentary session, a number of committees pass motions requiring that the documents provided by a witness shall be distributed only once they are available in both official languages.77 Beginning in 2021, some committees of the House of Commons have passed a motion providing that documents not coming from a federal department or translated by the Translation Bureau must be sent for linguistic review by the Bureau before being distributed to members.78

This type of motion illustrates the potential conflict between the right of parliamentarians to receive documents in the official language of their choice and the right of witnesses to use English or French in their interactions with Parliament. Following a complaint filed with the Office of the Commissioner of Official Languages in 2004, an application for remedy was made to the Federal Court to contest the fact that a parliamentary committee refused to distribute reference documents in one language only. The applicant, Howard P. Knopf, claimed that the practice was contrary to his right to use the official language of his choice before a parliamentary committee as provided for by section 4(1) of the OLA.

The Federal Court, Trial Division, held in 2006 that this practice does not infringe that right. In the Court’s view, this right, as set out in section 4(1) of the OLA, allows all individuals to use their preferred official language in the debates and proceedings of Parliament, but does not include the right to distribute documents to the members of a committee. The decision to distribute documents falls under the absolute authority of parliamentary committees to manage their internal procedures and is protected by parliamentary privilege. The Court concluded that the language rights of the applicant were not infringed.79 The Federal Court of Appeal upheld in 2007 the conclusions of the Trial Division, then the Supreme Court of Canada denied in 2008 the application for leave to appeal, thereby putting an end to this case.80

In practice, as was the case during the 42nd Parliament, a parliamentary committee may disregard its own rule after adopting a motion providing for the distribution of documents submitted to it in both official languages.81

Languages other than English and French may be used in the debates of the House of Commons, but in moderation and preferably with advance notice.82 For example, members have spoken in Inuktitut, Mohawk, Japanese, Greek, Latin, Gaelic, Punjabi and sign language.

In November 2018, the House of Commons adopted a report on the use of Indigenous languages in proceedings of the House of Commons and committees, which the Standing Committee on Procedure and House Affairs had presented five months earlier.83 Upon providing advance notice, it is now possible for MPs to obtain simultaneous interpretation services into English or French if they decide to speak an Indigenous language. In addition, their speeches are transcribed in the Indigenous language spoken in the House Debates or committee Evidence, together with the English and French transcripts. In January 2019, Robert-Falcon Ouellette became the first MP to give a speech in Cree and have it interpreted simultaneously into English and French for his colleagues.84 In November 2021, Lori Idlout became the first MP to be sworn in in Inuktitut.85

Similar permissions for the use of other languages have been given in the Senate, as long as English and French translations are provided in advance.86 In May 2006, Senator Eymard Corbin introduced the following motion to recognize the right to use Indigenous languages in Senate proceedings:

That the Senate should recognize the inalienable right of the first inhabitants of the land now known as Canada to use their ancestral language to communicate for any purpose; and

That, to facilitate the expression of this right, the Senate should immediately take the necessary administrative and technical measures so that senators wishing to use their ancestral language in this House may do so.87

The motion was debated in the Senate on a number of occasions and was referred to the Standing Committee on Rules, Procedures and the Rights of Parliament for more detailed consideration. The committee heard various witnesses and then completed a fact-finding trip to Nunavut to observe the measures its legislature has taken to provide simultaneous interpretation of its debates. The committee published a report in April 2008 that recommended

The report of the Standing Committee on Rules, Procedures and the Rights of Parliament was adopted on division on 14 May 2008. A few debates took place in Inuktitut in the Senate between 2010 and 2014,89 as well as a small number of speeches in this language in 2017 and 2019. Contrary to the Senate committee’s recommendation, the use of this language has not been reviewed since 2008.

That said, in March 2017, the Standing Senate Committee on Aboriginal Peoples published an Inuktitut translation of a report on housing in Inuit Nunangat, as well as the associated executive summary and recommendations.90 Since then, it has not been uncommon for witnesses to speak in an Indigenous language during the committee’s work.91 In June 2019, the Special Senate Committee on the Arctic had its entire fourth report translated into Inuktitut and published excerpts in three other Indigenous languages.92 In 2022, the Standing Senate Committee on Fisheries and Oceans had its fourth report translated into various Indigenous languages.93

Finally, the Speech from the Throne on 23 November 2021 marked a first in Canadian parliamentary history, as the Governor General of Canada, Her Excellency the Right Honourable Mary May Simon, delivered it in three languages: English, French and Inuktitut.

The emergence of new technologies and new means of communication such as social media raises questions about the use of official languages in Parliament. Parliamentarians are turning to social media more often, frequently using their personal accounts to communicate with the public and to promote their work. Some parliamentarians use only one official language, while others use two. In addition, the Senate and the House of Commons have institutional bilingual accounts on various platforms, including X, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn and YouTube.

In 2014–2015, the Commissioner of Official Languages conducted an investigation into the use of official languages on ministers’ Twitter accounts. The Commissioner concluded that government officials who interact on social media must communicate with the public in both official languages.94 In June 2021, the House of Commons Standing Committee on Official Languages recommended that the use of both these languages on social media be subject to the modernized OLA.95 An Act for the Substantive Equality of Canada’s Official Languages, which received Royal Assent in June 2023 and modernized the OLA, did not directly address this issue, but it did extend the concept of “communication” to electronic and virtual forms, encompassing social media.96

Between 2015 and 2019, a number of Senate and House of Commons committees launched e-consultations as part of their proceedings. Currently, there are no strict procedural rules covering the use of such a tool by committees, particularly regarding the relevant linguistic obligations. Although questionnaires to date have been publicly posted online in both official languages, there are still questions surrounding the requirement to translate and publish data received in both official languages.

As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, several parliamentary institutions around the world have had to modify their practices and procedures to carry out hybrid or virtual meetings, including Canada’s House of Commons and Senate, as well as their respective committees.97 The language requirements set out in the Constitution and the OLA continue to apply in spite of these changes.

The House Standing Committee on Procedure and House Affairs is aware of the challenges arising from hybrid and virtual sittings and meetings. In order to help MPs carry out their parliamentary duties during the COVID-19 pandemic, the committee carried out a study and presented its report on 15 May 2020.98 After studying language issues in particular, the committee recommended

This committee again examined simultaneous interpretation and the challenges of hybrid and virtual sittings in Parliament in a report tabled in July 2020. Its recommendations included adopting standards to help safeguard interpreters against injuries and fatigue, and reporting on injuries related to this new work environment.99

Despite adjustments to interpretation practices, problems persisted, prompting the House of Commons Standing Committee on Official Languages to take a closer look at the challenges facing interpreters during the COVID-19 pandemic. In a report released in May 2021, the committee proposed improvements to procedures and equipment necessary for interpreters to provide, at all times, a high-quality simultaneous interpretation service in both official languages in a safe work environment.100 The committee launched another study on interpretation services in Parliament in fall 2025.101

In the meantime, in February 2022, the union representing parliamentary interpreters filed a complaint against the Translation Bureau on their behalf.102 The Labour Program sided with the union the following year, leading the House of Commons and the Senate to change their practices to require individuals participating in parliamentary proceedings virtually to use approved headsets that meet ISO standards.

In January 2023, the House Standing Committee on Procedure and House Affairs presented a report on the future of hybrid proceedings in which it recommended amending the Standing Orders of the House of Commons to protect interpreters’ health and safety.103 The government responded favourably to this recommendation, but only by recognizing the permanent nature of hybrid sittings in Standing Order 15.1.104

In spring 2025, the federal government published an artificial intelligence strategy for the federal public service that did not specifically address parliamentary institutions.105 Under this strategy, the Translation Bureau plans to make use of artificial intelligence when translating official languages.106 However, the Commissioner of Official Languages alerted the federal government to the importance of ensuring human review of translations and keeping francophone perspectives and realities at the forefront of artificial intelligence strategies.107

In May 2012, Member of Parliament Alexandrine Latendresse introduced a private member’s bill, C-419, leading to the adoption of the Language Skills Act (LSA), which received Royal Assent in June 2013.108 The LSA requires that individuals appointed to certain key offices reporting to Parliament – namely officers of Parliament (also called “agents of Parliament”) – be able to readily speak and understand both official languages at the time of their appointment. Pursuant to section 2 of the LSA, this prerequisite applies to the following offices:

This bill was debated in Parliament following the appointment of Michael Ferguson – a unilingual anglophone at the time of his appointment – as the Auditor General of Canada. According to Ms. Latendresse, any officer of Parliament must be able to “communicate in both official languages in order to be able to properly carry out his or her duties.”110 Graham Fraser, Commissioner of Official Languages at the time and himself an officer of Parliament when the bill was introduced, expressed his support before the Standing Senate Committee on Official Languages:

What is important to point out when it comes to agents of Parliament is that they have direct obligations toward parliamentarians. So it is very important for parliamentarians to be understood in the language of their choice.111

The idea of respect for the language rights of parliamentarians has gained ground elsewhere in Canada. In her 2014–2015 annual report, Katherine d’Entremont, the former Commissioner of Official Languages for New Brunswick, said that her province’s Legislative Assembly should “take the Parliament of Canada’s lead, which adopted the Language Skills Act in June 2013.”112 In her report, she recommended that the Legislative Assembly of New Brunswick enact legislation establishing that the ability to speak and understand both official languages be a requirement for the appointment of officers of the assembly.113

In 2016, the federal government applied a new approach to all Governor in Council appointments, not only for Officer of Parliament appointments. The new selection processes, described by the government as “open, transparent, and merit-based,” are meant to reflect Canada’s linguistic diversity and require candidates to provide information on their second official language proficiency.114

In 2019 and 2021, calls were made to expand the scope of the LSA in light of the OLA’s modernization and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the federal government’s ability to provide services in both official languages.115 On 24 November 2021, a public bill was introduced in the Senate to add the position of Governor General to the list of positions in section 2 of the LSA.116 On 1 December 2021, a similar bill was introduced in the Senate, this time to add the position of Lieutenant Governor of New Brunswick to the list.117 These two bills died on the Order Paper, while a legal action on the appointment of a unilingual individual as Lieutenant Governor of New Brunswick is being heard by the Supreme Court of Canada.118

The Commissioner of Official Languages and the House of Commons Standing Committee on Official Languages looked into the language issues surrounding Governor in Council–appointed positions in 2022 and 2024, and the committee recommended changes to the LSA in this regard.119

A number of constitutional and statutory provisions relate to the use of the two official languages in Parliament and concern a range of parliamentary activities, such as debates, proceedings, the legislative process and the publication of various parliamentary documents. These provisions make Parliament an institution accessible to all English-speaking and French-speaking Canadians.

In recent years, the Senate and the House of Commons have also opened the door to the recognition of other languages, by taking measures governing the use of Indigenous languages. By promoting linguistic best practices, Parliament serves as a model of an institution that is accessible to all Canadians.

OLLO, “Observations to the Third Report of the Standing Senate Committee on Official Languages (Bill C‑13),” Third Report, 13 June 2023.

Yet, in March 2025, the Translation Bureau’s five-year business plan provided for eliminating several hundred positions through attrition, but this decision is not supposed to affect services to Parliament. See Canadian Association of Professional Employees (CAPE), Canadian government undermines French language with reckless Translation Bureau cuts, News release, 20 March 2025; and “Translation Bureau to cut a quarter of its workforce over next 5 years,” CBC News, 20 March 2025.

[ Return to text ]House of Commons, Debates, 28 January 2019, 1125 (Robert-Falcon Ouellette); and Robert‑Falcon Ouellette, “Honouring Indigenous Languages Within Parliament,” Canadian Parliamentary Review, Vol. 42, No. 2, Summer 2019.

The Translation Bureau can meet requests for approximately 60 Indigenous languages or dialects under current contracts. The Indigenous languages most requested from the Translation Bureau are Plains Cree, Mohawk, Ojibway, Desuline, Nunavik and Inuktitut. The services to Parliament are provided by freelance interpreters, as needed. See PSPC, Departmental Plan 2024–2025.

[ Return to text ]© Library of Parliament