In the 1980s, after a trend of privatizing utility industries around the world, policy‑makers began to turn their attention to reforming airport governance. At the time, most airports around the world were owned and operated by the public sector. One potential catalyst for airport reform in the 1970s and 1980s was the growth in air travel brought about by deregulation in the airline industry in North America and elsewhere. Rising passenger demand led to airport congestion and the need to invest in additional capacity and to innovate to increase the productivity of existing airport infrastructure. According to the 2001 report of the Canada Transportation Act (CTA) Review Panel, pressure on governments to limit borrowing and control public sector growth was another possible factor in changes to the governance of airports.2

To respond to these needs, countries around the world have moved towards commercialized airport governance by applying businesslike approaches and allowing market forces, incentives and mechanisms to affect the delivery of services. Airport commercialization models range from partial or full privatization (sale to private sector) to some form of public–private partnership, in which the management and/or operation of a public airport is carried out by the private sector by contract. Commercialization has several goals: to make airports more self-sufficient, more responsive to growing demand and investment needs, and more likely to offer services at a lower cost; it is also meant to allow airports to further develop their business. Other policy goals may be to generate revenue for the government from the sale or lease of the asset, or to promote regional development.

An important aspect of airport governance is whether an airport is subject to regulation with respect to user charges or business practices. Where there is increased private-sector involvement, such economic regulation is often introduced to limit the market power – which is monopolistic in many cases – of the private airport owner or manager. It is also not uncommon for publicly owned and operated airports to be subject to economic regulation in spite of their pursuit of public policy goals.

This paper describes the evolution of airport governance policy and commercialization in Canada, as well as airport commercialization undertaken elsewhere in the world, including in the United Kingdom (U.K.), the United States (U.S.), Australia and New Zealand. Some examples of airport commercialization in other countries are also briefly discussed. The final section examines recent proposals regarding the governance of Canadian airports.

From the 1960s through the 1980s, the management and operations of Canadian airports were the responsibility of the Canadian Air Transportation Administration (CATA), a division of Transport Canada. Investments in runways, terminals and other buildings were made from a capital fund provided by the Treasury Board. Revenues raised through landing fees, terminal charges and a ticket tax were credited to the Consolidated Revenue Fund. Airports were not required to be self-financing or to break even. Airport capacity decisions were made at the national level and did not necessarily reflect an individual airport's role and importance in its region.

Airport commercialization in Canada was undertaken as a means of funding the expansion of the airports system, making airports more competitive and viable and giving communities the flexibility to use them as tools for economic development. The first federal policy that considered reforming the management and operation of airports was issued in 1987 and was called A Future Framework for Airports in Canada.4 This policy allowed provincial, regional or local authorities to manage and operate airports through long-term ground leases drafted by Transport Canada. As a result, in 1992, not-for-profit “local airport authorities” (LAAs) were established in Montréal, Calgary, Edmonton and Vancouver.5

The government further reformed airport governance with the introduction of the National Airports Policy in 1994.6 Under this policy, small and regional airports were sold to their communities, usually for a nominal amount. Remote and arctic airports were either transferred to provincial or territorial governments or remained under federal government operation. The policy provided for the continued transfer of the management and operation of larger airports and airports serving provincial capitals on long-term leases to not-for-profit “Canadian airport authorities” (CAAs). These LAAs and CAAs formed the National Airports System (NAS), for which Transport Canada made a commitment to guarantee the long-term viability. Today, the NAS handles over 90% of total air traffic in Canada and includes the 21 leased LAA and CAA airports, three airports that were transferred to territorial governments and one that was transferred to a municipal government (Kelowna).

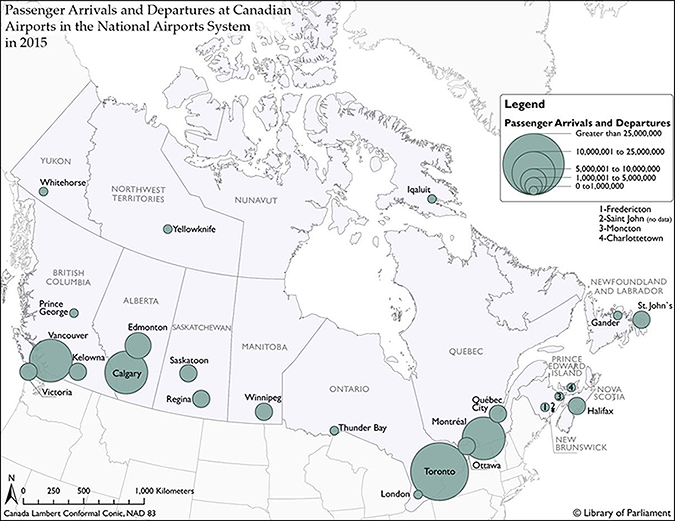

Figure 1 shows a map of the NAS airports, and information on the number of passengers leaving and arriving at each airport in 2015. Toronto Pearson International Airport had the highest number of passengers (over 39.6 million) of all the NAS airports, while the airport in Iqaluit, Nunavut, had the fewest (156,633 passengers).7

Figure 1 - Passenger Arrivals and Departures at Canadian Airports in the National Airports System in 2015

Figure 1 contains a map showing the Canadian cities with airports in the National Airports System. Using five categories, the map indicates the number of passengers arriving at and departing from the airports in 2015.

In the “greater than 25 million passengers” category is the airport in Toronto, Ontario.

In the category “10 million and one to 25 million passengers” are the airports in Vancouver, British Columbia; Calgary, Alberta; and Montréal, Quebec.

In the category “5 million and one to 10 million passengers” is the airport in Edmonton, Alberta.

In the category “1 million and one to 5 million passengers” are the airports in Victoria and Kelowna, British Columbia; Regina and Saskatoon, Saskatchewan; Winnipeg, Manitoba; Ottawa, Ontario; the city of Québec; Halifax, Nova Scotia; and St. John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador.

In the category “fewer than 1 million passengers” are the airports in Whitehorse, Yukon; Yellowknife, Northwest Territories; Iqaluit, Nunavut; Prince George, British Columbia; London and Thunder Bay, Ontario; Fredericton and Moncton, New Brunswick; Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island; and Gander, Newfoundland and Labrador.

No data was available for the airport in Saint John, New Brunswick.

Sources: Map prepared by Library of Parliament, Ottawa, 2017, using data from Natural Resources Canada (NRCan), Atlas of Canada National Scale Data 1:5,000,000 – Boundary Polygons, Ottawa, 2013; Transport Canada, “National Airports System,” List of airports owned by Transport Canada, accessed 9 May 2017; Government of Canada, Airports, Ottawa, 2015; and Statistics Canada, “Table 1-1: Passengers enplaned and deplaned on selected services – Top 50 airports,” Air Carrier Traffic at Canadian Airports, Catalogue no. 51‑203‑X, 2015. The following software was used: Esri, ArcGIS, version 10.3.1. Contains information licensed under Open Government Licence – Canada and Statistics Canada Open Licence Agreement.

Both LAAs and CAAs are private, self-financing, not-for-profit, non-share-capital corporate entities that do not pay income tax. Their leases on the federal infrastructure are for 60 years, with an option to renew for an additional 20 years. At the end of these leases, the authorities “must turn over a world-class airport, with no debt to the government.” 8

With respect to federal oversight, Transport Canada may audit the LAAs' records and procedures at any time and subject the LAAs to a performance review every five years. Also, public disclosure provisions in the ground leases require that certain documents be made available to the public and that public meetings be held after the end of each fiscal year. The CAAs are subject to even more public disclosure requirements under the Public Accountability Principles for Canadian Airport Authorities, which were introduced in 1994 to broaden airport authority accountability. According to the Principles, 60 days before a price increase is to apply, a CAA must publish notice of and justification for the increase in the local media. In addition to the public meeting at year‑end, a Community Consultative Committee, which includes airline industry representatives, must meet twice a year to discuss matters relating to the airport. The Principles also require that more documents, including the transfer agreements, be made available to the public and that contracts over $75,000 be put to public tender.9

Although some business practices are controlled through the ground-lease document, the LAAs and CAAs are not subject to economic regulation through legislation. Furthermore, the ground lease does not impose external review, approval or appeal processes on the prices the airport authorities set for parking, rent, landing aircraft, terminal use, etc. The LAAs and CAAs are also free to determine service levels within the safety regulatory framework.

The ground leases require the airport authorities to consult users about charges and investments, but do not require them to act on the users' recommendations or to provide an appeal mechanism. Airlines have suggested that they have little input into the airport authorities' decisions and that some airport authorities have been abusing their market power. They have alleged that some airport authorities have over-invested in infrastructure and that the prices and fees they charge to finance the investment have a negative effect on the prices that airlines can offer to their customers.10

A Transport Canada review in 199911 and an audit by the Auditor General of Canada in 200012 identified a number of concerns with the Canadian airport governance model:

The federal government has twice introduced new legislation – Bill C‑13 in 2003 and Bill C‑2014 in 2006, both of which died on the Order Paper as a result of elections being called – whose goal was to address some of these concerns. Bill C‑20 included, among other things, provisions that sought to address the access of air carriers to airport facilities, the public disclosure of airport information, the structure of the airport authorities' boards of directors, and the consultation of airport users and members of the public within the regions served by the airport authorities. According to the Institute for Governance of Private and Public Organizations, airport authorities have used Bill C‑20 as a reference document, adopting certain features of the proposed legislation.15

As illustrated in the following sections, airport commercialization models elsewhere in the world include the following:

No clear trend emerges among the pairings of airport governance and economic regulation models in these countries.

The U.K. was the first country to fully privatize some of its major airports. Under the Airports Act 1986, the public British Airports Authority (BAA) was dissolved and its property, rights and liabilities were transferred to a new company, BAA plc. Shares in BAA plc were subsequently offered for trade on the London Stock Exchange in July 1987. When it was first privatized, BAA plc owned and operated seven airports on a for‑profit basis, including the three London airports (Heathrow, Gatwick and Stansted), as well as the airports in Glasgow, Edinburgh, Aberdeen and Prestwick.

In 2006, a Spanish company, Ferrovial Aeropuertos S.A., led an international consortium that acquired BAA plc. In recent years, BAA plc has sold all but the Heathrow airport, mostly to other private-sector consortia. Today, BAA plc goes by the name of Heathrow Airport Holdings Ltd., and Ferrovial remains its largest shareholder, with a 25% stake. (The Caisse de dépôt et placement du Québec owns a 12.62% stake in the company.)16

The Airports Act 1986 also contained provisions requiring 15 municipal airports to be set up as companies at arm's‑length from the government. All 15 of these airports have since been privatized, in part or in whole, though the public sector does retain a stake in many of these airports.17

Overall, 52.6% of U.K. airports were owned fully by the private sector in 2016, compared to 21.1% owned fully by the public sector and 26.3% owned by a mix of private and public partners.18

As part of the 1986 legislation, the Civil Aviation Authority was authorized to administer economic regulation at all airports with revenues of over £1 million. Today, the Authority has powers to impose economic licensing on airports that pass a market power test under the Civil Aviation Act 2012. To date, Heathrow and Gatwick airports in London are the only airports to have passed this test. Economic licensing imposes conditions on airport owners concerning prices and service quality, among other things.19

Airports in the U.K. are also subject to the Airport Charges Regulations 2011, which implement European Union Directive 2009/12/EC on airport charges. The regulations apply to airports with over 5 million passengers per year in the two years prior to the current year. The regulations require airports to consult airlines about charges and infrastructure projects, to provide information about how airport charges are set, and to give advance notice of changes to airport charges.20 The Civil Aviation Authority has the power to investigate reports of airports not in compliance with the regulations.

Compared to the U.K., the U.S. has had very little involvement of the private sector in airport ownership. By and large, U.S. airports remain owned and operated by city or county governments. Funding for airport development comes from federal and state grants, passenger facility charges, airport and special facility bonds, and net income from airport revenues. Occasionally, terminals are privately financed at publicly owned and operated airports, such as at John F. Kennedy International Airport in New York, Chicago‑O'Hare International Airport and Detroit Metropolitan Airport.

In spite of continued public-sector ownership and (usually) management, U.S. airports that receive federal funds are subject to economic regulation. Statutory requirements on airport revenues prohibit the owners from diverting revenue to non‑airport purposes. Federal legislation also covers the setting of fees and charges levied on aeronautical users. The federal policy was consolidated in 1996 and confirmed that fees and charges were to be based on historic costs, and were to be fair and reasonable, and not unjustly discriminatory. Although the cases have not been frequent, airport operators have faced, and lost, legal challenges when users have perceived that fees and charges were unjustly discriminatory or that revenues had been diverted from airport purposes.21

Under the 1994 FAA [Federal Aviation Administration] Reauthorization Act, the U.S. Department of Transportation is authorized to adjudicate disputes between airlines and airports, and to issue a policy for determining the reasonableness of airport fees. While the FAA policy for determining reasonable airport fees at the local level was finalized in 1996, it has been revised formally and informally since then;22 the FAA published a complete version of the updated policy in 2013.23 One notable amendment in the policy is the increased flexibility of operators of congested airports to use price incentives to encourage aircraft operators to use their airports at off‑peak times or to move operations to less congested facilities.

The U.S. introduced the Airport Privatization Pilot Program (APPP) in 1996, which removed some of the requirements regarding federal grants and revenue diversion. The program allowed the lease or sale of five airports, depending on their size and the nature of their traffic; the five were to include one general aviation airport24 and no more than one large hub25. The FAA Modernization and Reform Act of 2012 increased the number of airports that can participate in the program from five to 10. Under the program, fees must be reasonable, but privatized airports can apply for federal grants and levy passenger facility charges. Revenue from the sale or lease of an airport can be used for non-airport purposes if approved by the majority of airlines serving the airport.

Two airports – Stewart International Airport in Newburgh, New York (in 2000), and Luis Muñoz Marín International Airport in San Juan, Puerto Rico (in 2013) – have completed the privatization process under the APPP. However, in 2007, Stewart International Airport reverted to public operation when the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey bought the airport's lease.26 Three other airports are in the process of completing the APPP privatization process.27

A 2016 paper from the Congressional Research Service identified a number of factors that may have contributed to the lack of privatization stimulated by the APPP, such as the time-consuming nature of the APPP application process, the regulatory requirements of the program (some of which have been criticized as being overly restrictive or vague), and airport operators' already sufficient access to funding.28

Prior to commercializing some of its airports, the Australian Commonwealth (federal) Government owned all of the large international airports in Australia, with the exception of the one in Cairns, and operated them through the Federal Airports Corporation. Despite the public ownership and operation, prices charged for services at the government-owned airports were under surveillance by another federal organization, the Prices Surveillance Authority.

Between 1997 and 2003, Australia sold 50‑year leases for 22 airports to private entities, but it retained ownership of the infrastructure. Until July 2002, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) regulated the prices charged and the service quality provided by private, for‑profit operators. The Australian Productivity Commission reviewed this ACCC price regulation after five years; the Commission's 2002 report advocated the removal of price cap regulation.

The Commission found that price cap regulation had led to airport profit volatility during the profound downturn in world aviation in 2002, which was exacerbated in Australia by the bankruptcy of Ansett Australia, the country's second-largest domestic air carrier. The Commission stated that the price cap regime threatened the financial viability of Australian airports and the provision of an essential service to the Australian public. It also said that, because the regulator intervened frequently, the compliance costs were very high for airports. The Commission concluded that that there was a significant risk that the regulator would approve airport price increases for unnecessary investments, given the information asymmetry inherent in the relationship between firms operating the airports and the regulator.30

In July 2002, price regulation was replaced with price monitoring at the seven major airports (Adelaide, Brisbane, Canberra, Darwin International, Melbourne, Perth and Sydney). Price monitoring was seen as a better option than the price cap regime, because the monitoring agency could take external factors into account when evaluating a firm's prices, and this was expected to reduce the firm's profit volatility and risk of failure.

Following another review released in April 2007,31 the federal government decided to continue the price-monitoring approach to regulation of aeronautical prices at five major airports (Adelaide, Brisbane, Melbourne, Perth and Sydney) for a further six years. In December 2009, it was announced that four airports (Canberra, Darwin International, Gold Coast and Hobart) would be required to report on their websites information related to various pricing, service quality and complaints-handling procedures. Following the 2012 release of the report of an inquiry by the Australian Productivity Commission,32 Adelaide Airport was moved from the price-monitored airports category to the group of airports that are subject to reporting requirements, because the commission found that the airport had limited market power. The disclosure requirements for the five airports (Adelaide, Canberra, Darwin International, Gold Coast and Hobart) continue today.

The ACCC continues to monitor prices and service quality at the four privately leased airports (Brisbane, Melbourne, Perth and Sydney). In its 2012 report, the Australian Productivity Commission inquiry recommended that service quality monitoring continue until June 2020.

Partial privatization of airports in New Zealand is an example of commercialization that falls between the approaches taken in the U.K. and the U.S. Majority ownership stakes in Auckland Airport and Wellington International Airport, two of New Zealand's three major international airports, were sold in the late 1990s to the private sector, with local city councils retaining minority shares in both airports. Christchurch Airport remains a public corporation jointly held by the city council and the New Zealand government.

All three of these airports are subject to government monitoring of prices, though no price cap has ever been introduced. The government has the right to introduce a price cap and can launch a review of pricing at any time under Part IV of the Commerce Act 1986.33

One such review occurred in 1998, when the Minister of Commerce requested that the Commerce Commission investigate the pricing of airfield activities (services enabling the landing and takeoff of aircraft) at the three principal airports. The Commission was to recommend whether price controls should be imposed on those airports. In its April 2002 report, the Commission recommended that the pricing of airfield activities at Auckland Airport should be controlled but did not recommend that controls be put in place for the prices of airfield activities at Wellington International and Christchurch airports. The Minister of Commerce responded in 2003 by deciding not to control prices at any of the three principal airports. She had concluded that the benefits to airlines and passengers of regulating prices at Auckland Airport were not sufficient to justify the administrative costs of enforcing such controls.34

To varying degrees, airports around the world have adopted models similar to the four discussed in the previous sections. For example, the Charles de Gaulle and Paris-Orly airports in Paris, France, are partially owned by the private sector, with the French government maintaining a 50.63% share in both cases.35 In Germany, the Düsseldorf and Frankfurt airports have both been partially privatized.36 In Japan, most airports are government-owned and operated, but the national government has sold long-term leases (or plans to sell such leases in the near future) to privatize operations at a number of airports.37 All three countries subject their airports to some form of economic regulation.

Since 2012, a number of recommendations have been made regarding the governance of Canadian airports. For example, the Standing Senate Committee on Transport and Communications recommended in its June 2012 interim report on Canadian air travel, and then again in its April 2013 final report, that “concurrent with the long-term plan of ending airport ground rents, Transport Canada transfer federally owned airports in the National Airports System to the airport authorities that operate them.” 38 The committee suggested that the relatively high ground rents paid by Canadian airport authorities contribute to the high cost of flying in Canada. The committee also found that the finite nature of the leases adds constraints on raising revenues for airport investments, particularly towards the end of the leases.

A 2014 report from the Institute for Governance of Private and Public Organizations recommended that the federal government “offer provinces and municipalities the opportunity to acquire the real estate assets and equipment of Canadian airports.” 39 Among other things, the Institute suggested that selling the airports to provincial or municipal governments would resolve the issue of ground rents and allow provincial and municipal governments to better integrate air transport with other modes of transportation.

In 2015, the most recent CTA Review Panel recommended that the federal government move within three years to a share-capital structure for larger airports, with equity-based financing from large institutional investors. As part of this recommendation, the CTA Review Panel suggested implementing the economic regulation of fees and charges, with the Canadian Transportation Agency responsible for oversight of those regulations. 40 In explaining the reasoning behind these recommendations, the CTA Review Panel noted “the benefit of increased private sector discipline in the management of large airports.” 41 The review panel also cited the challenges with airport investments at the end of leases, and the potential for airports and carriers to abuse market power in the absence of regulations.

In September 2016, the federal government hired Credit Suisse Canada to provide financial advice to the government on the CTA Review Panel's recommendations on airport governance. 42 According to media reports, the government does not intend to make this advice public. 43

Some stakeholders have criticized the possibility of privatizing the larger Canadian airports. For example, the Union of Canadian Transportation Employees has expressed concerns about the following:

Airport authorities in Ottawa, Vancouver and Calgary have also opposed the privatization of their airports, arguing that privatizing their facilities would increase customer fees and hurt the quality of service. 45

The International Air Transport Association has suggested that the federal government should make the elimination of the rents that it charges airports a higher priority than the consideration of airport privatization. 46

Data from a public opinion poll conducted in April 2017 indicated that members of the public also have concerns regarding the possibility of fully privatizing airports. A majority (53%) of respondents said that privatizing Canada's eight largest airports would be a “bad” or “very bad” idea. In contrast, 21% of respondents said that it was a “good” or “very good” idea. 47

In contrast, some think-tanks and airport authorities have expressed support for the privatization of Canada's largest airports. For example, a February 2017 report from the C. D. Howe Institute estimated that the federal government could raise between $7.2 billion and $16.6 billion for infrastructure investments if it sold its equity stakes in Canada's eight largest airports. 48

An op‑ed article from the Montreal Economic Institute also suggested that privatizing Canadian airports would be “good news indeed for the Canadian air travel industry, and ultimately for Canadian travellers,” because “[r]eplacing the current system of excessive rents based on a percentage of gross revenues with a tax on companies' profits would encourage airports to invest more and to reduce the fees charged to carriers and consumers.” 49

According to media reports, the Greater Toronto Airports Authority, the operator of Toronto Pearson International Airport, is open to letting the private sector have a stake in the airport as a method of funding a transit hub on airport grounds. 50

Historically, many countries have turned to some form of commercialization in an effort to ease the financial and operational pressures at their airports and to improve the quality and cost of airport services. At one end of the spectrum, the U.K. has fully privatized many of its larger airports. At the other end, the U.S. has maintained public ownership of all but one airport, while allowing public–private partnerships to manage some airports. Between those two ends of the spectrum, Australia and Japan have sold long-term leases for some of their airports, while certain airports in New Zealand, France and Germany have sold some shares to the private sector. These countries all have some form of economic regulation (such as price caps or price monitoring) in place for airports.

The Canadian approach is noticeably different. To manage the operations of Canada's largest airports, not-for-profit airport authorities with long-term leases have been created. These authorities must pay rent to the federal government. At the end of the lease, each authority must return a “world-class,” debt-free airport to the federal government. Unlike other countries, Canadian airport authorities are not subject to economic oversight by the government.

Some stakeholders have suggested that the governance of airports in the National Airports System could be improved, and that some of these airports are in a position to abuse their market power. Two government bills (one introduced in 2003, the other in 2006) that died on the Order Paper attempted to address some of the deficiencies in airport authority governance noted by both Transport Canada and the Auditor General of Canada in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Today, the federal government is considering the recommendation of the 2015 CTA Review Panel to sell shares of its airports to the private sector, a possibility that has elicited much debate among stakeholders.

* This publication is an updated version of a 2007 Library of Parliament publication of the same title by Allison Padova. [ Return to text ]

† Library of Parliament Background Papers provide in-depth studies of policy issues. They feature historical background, current information and references, and many anticipate the emergence of the issues they examine. They are prepared by the Parliamentary Information and Research Service, which carries out research for and provides information and analysis to parliamentarians and Senate and House of Commons committees and parliamentary associations in an objective, impartial manner. [ Return to text ]

© Library of Parliament