This Background Paper presents an overview of the Canadian seal harvest, including the following topics:

There are six species of seals found off the Atlantic coast of Canada: harp, grey, hooded, harbour, ringed, and bearded – although Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) notes that the last two typically reside in Arctic waters.

Of the six species noted above, “harp seals account for almost all the seals harvested commercially in Canada, with only a small harvest of grey and hooded seals.”2 There are no commercial hunts for harbour, ringed, or bearded seals in Canada, although subsistence harvests exist for all three species.

DFO estimates the current Northwest Atlantic harp seal population to be about 7.4 million animals, – six times larger than in the 1970s – and considers the population to be abundant and healthy. The Canadian harp seal stock can be divided into three breeding herds: off the coast of southern Labrador/northern Newfoundland; near the Magdalen Islands; and in the northern Gulf of St. Lawrence.

DFO puts the number of Canadian Atlantic grey seals at 505,000 animals. Grey seals can be found on both sides of the North Atlantic Ocean. In Canada, the species is present in the Gulf of St. Lawrence off the shores of Quebec, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia, and Newfoundland and Labrador.

The Northwest Atlantic hooded seal population is estimated to be 593,500 animals (growing at a rate of 0.5% per year). This population has its young off the coasts of southern Labrador and northern Newfoundland, the southern Gulf of St. Lawrence, and the Davis Strait (situated between Greenland and Canada). After the breeding (or whelping) season, the population disperses “to feed and migrate to the moulting areas off southeast Greenland … [and then] migrate along the Greenland coast to Baffin Bay and Davis Strait where they feed before returning to the breeding areas in late winter.”4

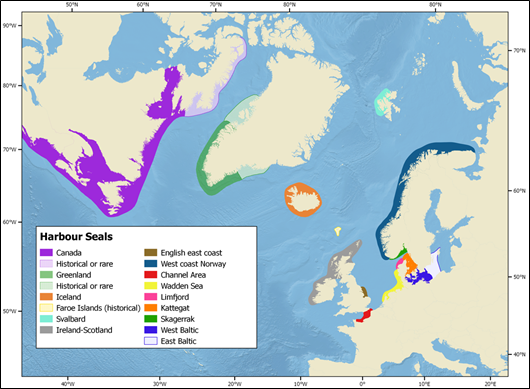

Harbour seals can be found along the temperate and sub-Arctic marine coastlines of the Northern Hemisphere (see Figure 1). The Canadian Atlantic harbour seal population is estimated by DFO to be between 20,000 and 30,000 individuals. A Canadian harbour seal population is listed under Schedule 1 of the Species at Risk Act5 as endangered – the landlocked Harbour Seal Lac des Loups Marins subspecies (160 km east of Hudson Bay). It is believed that overexploitation was a key factor in the population decline of the subspecies.6

Figure 1 - Range of North Atlantic Harbour Seal Stocks

The map depicts the current and historical range of North Atlantic harbour seal stocks. This range primarily consists of the coastal areas of eastern and northern Canada, Greenland and Norway. Other coastal areas where harbour seals can be found include Iceland, Ireland and Scotland, among others.

Source: North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission, “North Atlantic Stocks,” Harbour Seal.

Ringed seals can be found primarily in the high Arctic. Unlike other seal species, ringed seals give birth to their pups in lairs under the snow cover created by rough sea ice instead of on the ice, making it difficult to count all individuals at one time and making aerial, ground-based, and ship-based surveys ineffective means of measuring abundance. Although most abundance estimates are incomplete, the North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission estimated the Northeastern Canada–Baffin Bay–West Greenland stock (the only ringed seal population that can be found in Canadian waters) to be approximately 1.3 million individuals in the late 1990s.

Globally, bearded seals can be found throughout the Arctic and sub-Arctic regions. Population data are very limited, owing to the species’s “remote and broad distribution.” Past estimates have put their abundance at anywhere between 500,000 and 1 million individuals across their entire range.7

In Canada, the seal harvest is managed as a fishery by the federal government through DFO, whereby the Minister is granted this authority through legislation, including the Fisheries Act,8 the Oceans Act9 and the Species at Risk Act, as well as through the Marine Mammal Regulations (MMR).10 The Commercial Fisheries Licensing Policy for Eastern Canada (1996) – created under the authority of the Fisheries Act – governs the issuance of sealing licences.11

This fishery is also managed using the 2011–2015 Integrated Fisheries Management Plan for Atlantic Seals as a guidance document.12 This plan applies to the harvest of all six seal species. However – as noted above – harbour, ringed, and bearded seals are not commercially fished in Canada. Nevertheless, subsistence harvests are in effect for these three species because “Indigenous peoples in Canada have a constitutionally protected right to harvest marine mammals, including seals, as long as the harvest is consistent with conservation needs and other requirements.”13

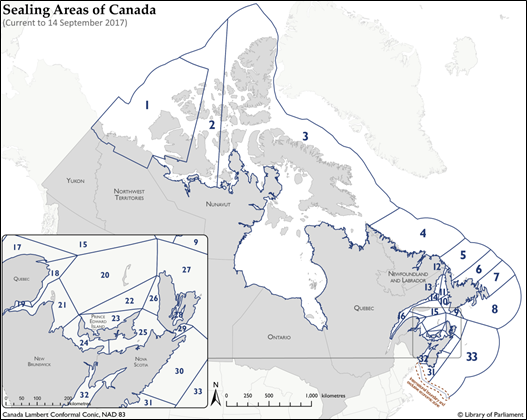

Three broad seal management areas are identified by the department for this commercial fishery; these are further broken down into 33 Sealing Areas by the MMR (see Figure 2 below):

Figure 2 - Sealing Areas of Canada

The map depicts Canada’s 33 Sealing Areas located in the Arctic, Newfoundland and Labrador, and the Gulf of St. Lawrence. The numbering of areas begins with Sealing Area 1 in the western Arctic, continuing along Canada’s northern and eastern coasts to Sealing Area 33 off the coast of Nova Scotia.

Source: Map prepared by Library of Parliament, Ottawa, 2017, using data from: Government of Canada, Atlas of Canada National Scale Data 1:5,000,000 – Boundary Lines, 2013; Government of Canada, Atlas of Canada National Scale Data 1:5,000,000 – Boundary Polygons, 2013; Government of Canada, Atlas of Canada National Scale Data 1:1,000,000 – Boundary Polygons, 2014; Marine Mammal Regulations, SOR/93-56; and Fishing Zones of Canada (Zones 4 and 5) Order, C.R.C., c. 1548. The following software was used: Esri, ArcGIS, version 10.3.1. Contains information licensed under Open Government Licence – Canada.

Pursuant to the MMR, the commercial harvest season for harp and hooded seals (in Sealing Areas 4–33) is from 15 November to 14 June (although it is closed from 15 February to 15 March to allow the seals to whelp and nurse their pups). Also pursuant to the MMR, the commercial harvest season for grey seals (in Sealing Areas 4–33) takes place from 1 March to 31 December. It is important to note that, for various reasons, harvest seasons can be subject to change at any time through a Variation Order issued by DFO.

Subsistence harvests14 (for Indigenous peoples and non-Indigenous coastal residents living north of latitude 53°N in Labrador and in the Arctic) can occur year-round, with the exception of the ringed seal subsistence harvest in Labrador, which – pursuant to the MMR – is only permitted from 25 April to 30 November. Seal harvests for food, social and ceremonial (FSC)15 purposes can occur year-round, without exception.16

Harvesters require either a commercial or personal use17 licence to harvest seals. In 2016, DFO reported that of 9,710 commercial licence holders, less than 1,000 of them were active.18 The department explained that the discrepancy between the number of commercial licences issued and the actual participation in the fishery could be explained by two factors: a 2004 freeze on the issuance of new commercial sealing licences and the fact that many of the unused licences are renewed annually simply to maintain eligibility in the hopes of more favourable prices for pelts and other seal-derived products in the future.19 Note that subsistence and FSC seal harvests do not require licences and are thus not included in the above participation data.

To address concerns regarding the humaneness of this fishery, the MMR were amended in 2009 to require that Canadian seal hunters (also known as “sealers”) use a three-step process (striking, checking and bleeding), which ensures that the animals are harvested humanely. Training on the three-step process is required for all those wishing to participate in the commercial seal fishery. Those harvesting with personal use licences must also use the three-step process. The MMR also restrict the tools used to harvest seals to the following: high-powered rifles, shotguns firing slugs, clubs and hakapiks.20

Atlantic seal hunting can be traced as far back as the early Dorset culture, 3,000 years ago, and there is early evidence of seal harvesting by the Thule Inuit and Labrador Innu. Seals were also an important catch for fishing fleets from Europe as far back as the 16th century, and in Canada from the 18th century onwards.21 According to the Canadian Sealers Association “[f]or thousands of years, seals have provided food, clothing and heat for people living in challenging northern regions” and continue to do so for many Indigenous peoples and northern communities.22

In the Arctic, sealing continues to play an important role in Inuit life, which can be seen in “the rich vocabulary in the Inuktitut language for different species, varieties and characteristics of seals.”23 Indeed,

[s]eals have always been central to Inuit culture, sustaining traditional sharing customs, conveying a special knowledge of the seal and its ecosystem, and keeping skills and values alive from generation to generation. [In addition,] seal meat continues to be a nutritious alternative to store-bought groceries shipped from distant cities.24

Moreover, “seal meat continues to be a nutritious alternative to store-bought groceries shipped from distance cities.”25

Parliament has demonstrated its support for the Canadian seal harvest by passing legislation highlighting its economic and socio-cultural significance. On 16 May 2017, Bill S-208, An Act respecting National Seal Products Day, received Royal Assent, marking 20 May in perpetuity as National Seal Products Day in Canada. This day seeks to, among other things, recognize “the importance of the seal hunt for Canada’s Indigenous peoples, coastal communities and entire population.”26

As shown in Table 1 below, Canadian seal landing values peaked in 2006, with meat and pelt values exceeding $30 million. Landed values saw a significant decline in subsequent years due to a dramatic reduction in seal pelt landings (from 297,252 pelts in 2006 to 35,842 pelts in 2015), among other factors.27

| Year | Landingsa | Landed Values ($) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Pelts | Meat (kg) | ||

| 2004 | 319,885 | 176,476 | 14,862,415 |

| 2005 | 290,242 | 6,725 | 16,293,459 |

| 2006 | 297,252 | 27,001 | 30,090,106 |

| 2007 | 223,641 | 51,154 | 11,731,050 |

| 2008 | 215,440 | 35 | 6,773,439 |

| 2009 | 53,531 | 144,427 | 816,222 |

| 2010 | 67,007 | 53,788 | 1,292,389 |

| 2011 | 37,918 | 1,751 | 657,710 |

| 2012 | 67,567 | 9,647 | 1,524,659 |

| 2013 | 95,221 | 19,961 | 2,635,339 |

| 2014 | 59,486 | 27,720 | 1,665,867 |

| 2015 | 35,842 | 3,645 | 1,126,912 |

Note: a. “Landings” are defined as “the part of the catch that is put ashore.” See Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Landings.

Source: Table prepared by the author using data obtained from personal communications with Legislation and Parliamentary Affairs, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, 9 August 2016 and 21 July 2017.

While the bulk of seal-derived products from the commercial harvest have traditionally been for export, seals are also harvested and transformed into products for the Canadian market, including for clothing, health supplements, and meat for both human and animal consumption. DFO “encourages the fullest possible commercial use of seals”28 and supports the development of new applications for seal products.

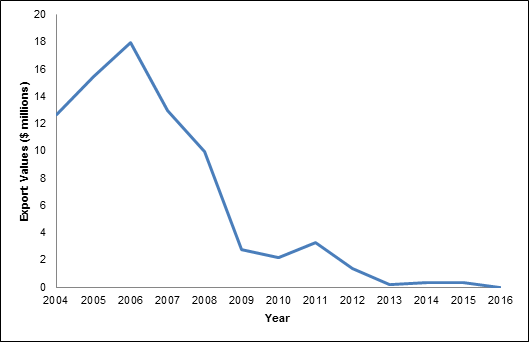

Canada has long been the world’s largest exporter of seal products, including pelts, oil and meat, with markets in more than 40 countries.29 Of the three seal products, pelts have traditionally had the highest export value. Figure 3 depicts the evolution of the export value of seal products between 2004 and 2016. It shows that export values peaked in 2006 at $17.9 million and then declined sharply. In 2016, no seal exports were reported. DFO attributed the high 2006 export value “to an unusually high price per seal pelt of $100” as compared to the average market price of $27 after 2006.30

A decrease in demand for luxury goods and a global decrease in fur prices following the global recession in 2009 have also had a negative impact on Canadian seal product exports. In addition, the European Union (EU) ban on the importation and sale of seal products instituted in 2009 further harmed this industry.31

Figure 3 - Seal Products (Pelts, Oil and Meat), Export Values, 2004–2016

Source: Figure prepared by the author using data obtained from personal communications with Legislation and Parliamentary Affairs, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, 9 August 2016 and 21 July 2017.

Data provided by DFO indicate that the destinations for Canadian seal pelt exports varied considerably between 2000 and 2015. Nevertheless, the following countries were among the leading markets for Canadian seal pelts during this period:

By way of contrast, in 2015, China was the largest market for Canadian seal pelts, but the number imported was just 686 pelts.

The primary export market for seal oil (used, for example, in Omega 3 health products) is Asia, more specifically China and South Korea.33 Seal meat exports have generally also been destined for Asian markets, such as South Korea, Japan, Taiwan and Hong Kong.34 It is worth noting that prior to export, seal meat must be processed in a Canadian Food Inspection Agency–inspected facility. The seal meat may also need to meet additional inspection standards due to regulations in importing countries.

Canada has come in for international criticism regarding the humaneness of its seal harvesting practices. Over the years, anti-sealing campaigns in Canada and abroad have been active in voicing their opposition to sealing, which hampers the promotion and marketability of seal-derived products.

In 2009, the EU instituted a ban on the importation and sale of seal products (with the exception of those resulting from traditional hunts by Indigenous communities).35 The federal government challenged this decision at the World Trade Organization (WTO), arguing that the ban was discriminatory in nature and went against the trade rules of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade. In 2013, the WTO confirmed that the EU’s ban was indeed discriminatory and treated Canadian seal products unfairly. However, it also noted that a ban could be justified on public moral grounds and that the EU’s exception for Indigenous communities was reasonable but was “formulated and applied in a discriminatory manner as in fact the Canadian Inuit are not currently benefiting from it.”36 Canada appealed the WTO decision to the Appellate Body, which in May 2014 upheld the earlier panel’s conclusion.37

In October 2014, Canada and the EU came to an agreement that “sets out the framework for cooperation to ensure that Canadian Indigenous communities are treated the same as any other Indigenous community seeking access for seal products in markets within the European Union.”38 On 25 October 2015, the Government of Nunavut (Department of Environment) was added to the EU’s list of recognized bodies under the Inuit Exception,39 which enables the Government of Nunavut to “certify sealskins as having been harvested according to the rules of the exemption.”40 The Government of the Northwest Territories was also added to the EU’s Inuit Exception list on 14 February 2017.

In October 2016, Canada and the EU signed the Canada–European Union Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA). Although fishery products are included in the text, there is no mention of seal products. However, it is worth noting that, in the statement released at the signing ceremony of CETA, leaders recognized “the importance of [their] joint statement on access to the EU of seal products from Indigenous communities in Canada,” and they committed to continue to cooperate in this framework.41

Various factors have been identified by DFO as having a potential impact on the health and stability of Canada’s seal populations.

As a result of low participation in the seal harvest, the yearly total allowable catches (TAC) set by DFO for the commercial harp, grey, and hooded seal harvests are not being reached. In 2016, the harp seal TAC was set at 400,000 animals (only 66,800 were landed), the grey seal TAC was set at 60,000 animals (only 1,612 were landed), and the hooded seal TAC was set at 8,200 animals (no landings were reported).42

Moreover, increases in seal populations resulting from a smaller seal hunt could reduce local populations of prey species on which seals depend and potentially affect ecosystems and other local fisheries.

Finally, the decreasing quantity and quality of sea ice is of concern because it comprises an important part of seal habitat (e.g., ringed seals use pockets created by sea ice as birthing lairs).43 Diminishing sea ice could thus endanger both seal stocks as well as commercial and subsistence fisheries.

In 2015, in order to meet the export market requirements set by the EU, the Government of Canada established the Certification and Market Access Program for Seals (CMAPS), a five-year program that committed $5.7 million through to 2019–2020. The goal of CMAPS is to

fund the development of certification and tracking systems so that seal products harvested by Indigenous communities can be certified to be sold in the European Union (EU) … and it will also support the broader commercial seal industry to access world markets.44

On 28 January 2016, a contribution agreement worth $150,000 was signed by the governments of Canada and Nunavut as part of CMAPS. The Nunavut government will

use the new funds to lead a number of projects in collaboration with the Nunavut Arts and Crafts Association and others. These projects aim to increase the amount and market value of sealskin products, reinvigorate the industry overall, and bring awareness and opportunity to Inuit about accessing the EU and other markets.45

For its part, the Government of Nunavut has clearly stated that, whatever the state or profitability of the commercial seal harvest, traditional seal hunting – which is central to the cultural fabric of Inuit communities – will continue.46

† Library of Parliament Background Papers provide in-depth studies of policy issues. They feature historical background, current information and references, and many anticipate the emergence of the issues they examine. They are prepared by the Parliamentary Information and Research Service, which carries out research for and provides information and analysis to parliamentarians and Senate and House of Commons committees and parliamentary associations in an objective, impartial manner. [ Return to text ]

© Library of Parliament