The Global Compact on Refugees1 (GCR) and the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration2 (GCM) are international agreements negotiated by states, with the support of the United Nations (UN) and input from civil society, that cover the movement of people. Based on pre‑existing international conventions and practices, they set out objectives for how migration management and refugee protection should be approached within states of origin, states of transit and host states. They promote effective international cooperation in managing migration by addressing the disproportionately heavy burdens certain countries are carrying and by seeking to replace the previous ad hoc reactions to major flows of migrants. While not adopted unanimously, the agreements have the support of a large majority of states in the international community.

Although refugees and migrants are sometimes referred to as one and the same, their differences explain the existence of two separate but complementary agreements. On the one hand, refugees3 are protected by a well‑established international legal framework, applicable in cases of flight due to persecution, violence, or other conditions related to vulnerability in their home countries. Migrants,4 on the other hand, are a broader group that includes individuals who change their country of residence, irrespective of the reason. While migrants and refugees are both entitled to universal human rights and fundamental freedoms, the two global compacts take into account different underlying obligations for states.

The global compacts are not legally binding. Although the months of negotiations behind their creation and the various iterations of their commitments resembled a treaty‑making process, they are not international conventions. Thus, they encourage states to act according to certain goals rather than compel them to do so.

The following sections of this publication address recent steps in the development of both global compacts before delving into their content. Canada’s contribution towards the negotiation of the global compacts is then addressed, followed by a discussion of what Canada is doing in respect of the agreements.

On 19 September 2016, the UN General Assembly (UNGA) unanimously adopted the New York Declaration for Refugees and Migrants (New York Declaration).5 The New York Declaration was an expression of political will that the protection of refugees and migrants and the support to countries sheltering them should be addressed as shared international responsibilities. It endorsed commitments applying jointly to refugees and migrants, as well as those applying to refugees and migrants separately. It also set in motion two independent processes that would lead to the adoption of actionable objectives represented in the two global compacts.

The development of the GCR included consultations led by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) with states, international organizations, refugees, civil society, the private sector and experts.6 The starting point for the process included discussions surrounding the practical application of responsibilities listed in the Comprehensive Refugee Response Framework (CRRF), as set out in Annex I of the New York Declaration.7 As explained below, the CRRF consists of various state actions and objectives that contribute to a comprehensive response to any large movement of refugees.

A series of thematic discussions between states held in 2017 was followed by consultations on successive drafts of the GCR between February and July 2018. These were complemented by hundreds of written contributions from UN member states and other stakeholders.8

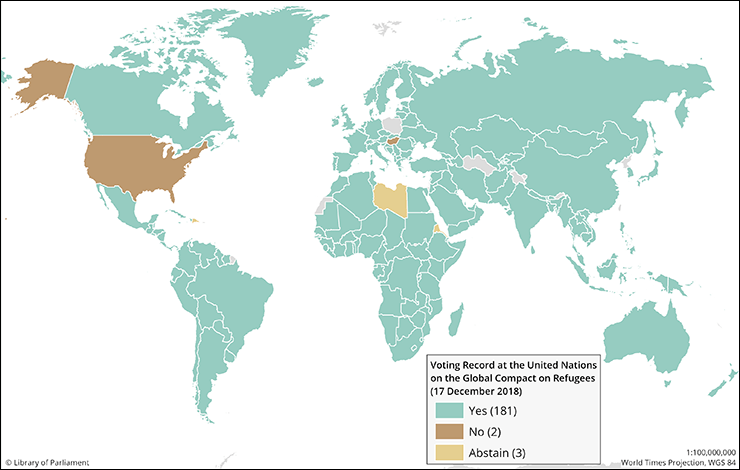

The GCR was officially endorsed by the UNGA on 17 December 2018, with 181 votes in favour, two against (Hungary and the United States) and three abstentions (Dominican Republic, Eritrea and Libya), as seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1 – International Support for the Global Compact on Refugees

Sources: Map prepared by Library of Parliament, Ottawa, 2019, using data obtained from Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, “Global Administrative Unit Layers (GAUL),” GeoNetwork, 2015; and United Nations General Assembly, Vote Name: Item 65 A/73/583 Draft Resolution II: Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees ![]() (66 KB, 1 page), 55th Plenary Meeting, 17 December 2018. The following software was used: Esri, ArcGIS Pro, version 2.3.0.

(66 KB, 1 page), 55th Plenary Meeting, 17 December 2018. The following software was used: Esri, ArcGIS Pro, version 2.3.0.

The path towards the adoption of the GCM was set out in Annex II of the New York Declaration. The process was shepherded by a newly appointed Special Representative of the United Nations Secretary‑General for International Migration, the Honourable Louise Arbour, formerly the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights.9 Co‑facilitators Jürg Lauber, Permanent Representative of Switzerland, and Juan José Gómez Camacho, Permanent Representative of Mexico, were chosen by the President of the UNGA to oversee 18 months of consultations and negotiations by states, including a year of thematic, regional and multi‑stakeholder discussions covering all aspects of migration.10 Six further rounds of intergovernmental negotiations were held in New York, and on 13 July 2018, UN member states finalized the text of the GCM.

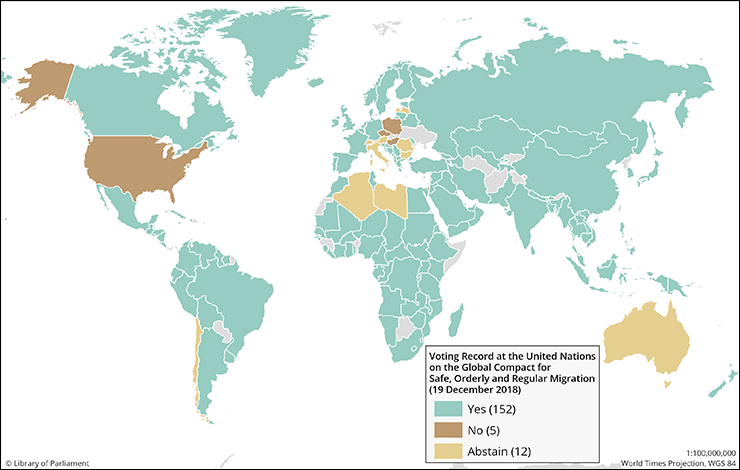

On 10 December 2018, the GCM was adopted by 164 governments at an intergovernmental conference in Marrakech. It was formally endorsed by the UNGA on 19 December 2018, with 152 votes in favour, five against (Czech Republic, Hungary, Israel, Poland and the United States) and 12 abstentions (Algeria, Australia, Austria, Bulgaria, Chile, Italy, Latvia, Libya, Liechtenstein, Romania, Singapore and Switzerland), as seen in Figure 2.

Figure 2 – International Support for the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration

Sources: Map prepared by Library of Parliament, Ottawa, 2019, using data obtained from Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, “Global Administrative Unit Layers (GAUL),” GeoNetwork, 2015; and United Nations General Assembly, Vote Name: Items 14 and 119 Draft resolution A/73/L.66 (as orally revised): Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration ![]() (66 KB, 1 page), 60th Plenary Meeting, 19 December 2018. The following software was used: Esri, ArcGIS Pro, version 2.3.0.

(66 KB, 1 page), 60th Plenary Meeting, 19 December 2018. The following software was used: Esri, ArcGIS Pro, version 2.3.0.

Prior to the adoption of the New York Declaration, Canada, in collaboration with Jordan, Fiji, Kenya, Lebanon and Turkey, led efforts to ensure international action and cooperation on refugees and migrants.11

With respect to negotiations leading up to the GCR, Canada engaged domestically with civil society as drafts were developed.12 Global Affairs Canada noted that Canada “advocated for the inclusion of gender‑sensitive language and the recognition of specific needs and capabilities of women and girls.”13

The Government of Canada also played a “leadership role” in advocating for the inclusion of “concrete, practical actions” in the GCM that reflect the views of civil society, including migrants themselves.14

The GCR is made up of four parts: an introduction, the CRRF, a detailed program of action, and measures for follow‑up and review.

The introduction sets out the background of the GCR, noting the urgency of increased burden sharing by states while reiterating the agreement’s non‑binding character. It also lists the guiding principles behind the initiative, including international refugee instruments, such as the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees.15

The four major objectives of the agreement are then laid out in paragraph 7. They consist of the following:

The introduction closes by acknowledging the importance of also working towards eliminating the reasons behind the movement of people:

All States and relevant stakeholders are called on to tackle the root causes of large refugee situations, … to promote, respect, protect and fulfil human rights and fundamental freedoms for all; and to end exploitation and abuse, as well as discrimination of any kind on the basis of race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth, disability, age, or other status.17

The second part of the GCR contains the CRRF in the form in which it appeared in the New York Declaration.18 The CRRF consists of a wide range of measures to be taken by states in order to prepare for, and respond to, large‑scale refugee situations. These include, among other detailed steps, the adoption of measures to support rapid reception and admission of refugees, and assistance for local and national institutions and communities receiving refugees.19

The third part of the GCR consists of a program of action to facilitate the application of

a comprehensive response in support of refugees and countries particularly affected by a large refugee movement, or a protracted refugee situation, through effective arrangements for burden‑ and responsibility‑sharing (Part III.A); and areas for timely contributions in support of host countries and, where appropriate, countries of origin (Part III.B).20

The program of action includes arrangements by states to share the burden of taking in refugees; measures for reception and admission of refugees; stipulations for settlement services; and commitments to solutions. The solutions include, but are not limited to, support to countries of origin and host countries, voluntary repatriation of refugees, resettlement and local integration.21

Lastly, provisions on how follow‑up and review of the GCR will proceed include a Global Refugee Forum, to be held every four years, high‑level officials’ meetings, to be held every two years, and the UNHCR’s annual report to the UNGA.22

The GCM contains a preamble, vision and guiding principles, a cooperative framework with 23 detailed objectives and commitments, measures on implementation, and details of follow‑up and review mechanisms.

Whereas international protection for refugees can be directly traced to the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees, the many dimensions governing migration rest on international norms represented in a variety of international instruments. For this reason, the preamble of the GCM includes a lengthy list of these instruments. For example, in addition to the core human rights treaties, the preamble mentions the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime, including the Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons Especially Women and Children; the Protocol against the Smuggling of Migrants by Land, Sea and Air; and the International Labour Organization conventions on promoting decent work conditions and labour migration.23

The GCM’s vision and guiding principles reflect intentions to, among other things, identify common understandings related to migration; acknowledge shared responsibilities of states; raise awareness of the particular vulnerabilities of women and child migrants; and optimize the overall benefits of migration. Mindful of state sovereignty, the GCM also reaffirms the right of states to determine their national migration policy. The agreement notes that, when envisaging legislative and policy measures, states may “[take] into account different national realities, policies, priorities and requirements for entry, residence and work.”24

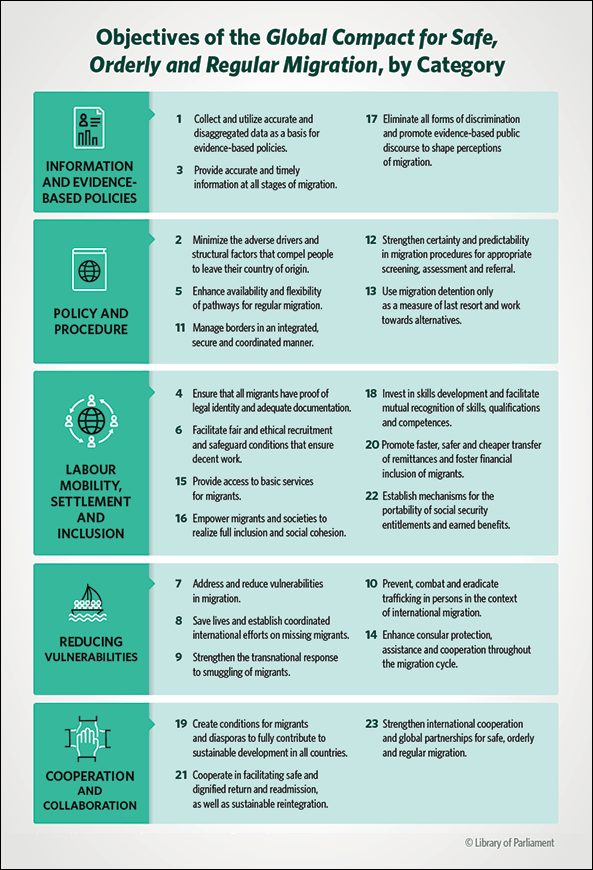

The GCM contains 23 objectives that promote safe, orderly and regular migration. Each objective consists of a commitment, reinforced by a detailed list of actions “considered to be relevant policy instruments and best practices.”25 The objectives can be classified into five broad categories, as illustrated in Figure 3:

Figure 3 – Objectives of the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration, by Category

| Information and Evidence‑based Policies |

1

Collect and utilize accurate and disaggregated data as a basis for evidence‑based policies. 3

Provide accurate and timely information at all stages of migration. |

17

Eliminate all forms of discrimination and promote evidence‑based public discourse to shape perceptions of migration. |

|---|---|---|

| Policy and Procedure |

2

Minimize the adverse drivers and structural factors that compel people to leave their country of origin. 5

Enhance availability and flexibility of pathways for regular migration. 11

Manage borders in an integrated, secure and coordinated manner. |

12

Strengthen certainty and predictability in migration procedures for appropriate screening, assessment and referral. 13

Use migration detention only as a measure of last resort and work towards alternatives. |

| Labour Mobility, Settlement and Inclusion |

4

Ensure that all migrants have proof of legal identity and adequate documentation. 6

Facilitate fair and ethical recruitment and safeguard conditions that ensure decent work. 15

Provide access to basic services for migrants. 16

Empower migrants and societies to realize full inclusion and social cohesion. |

18

Invest in skills development and facilitate mutual recognition of skills, qualifications and competences. 20

Promote faster, safer and cheaper transfer of remittances and foster financial inclusion of migrants. 22

Establish mechanisms for the portability of social security entitlements and earned benefits. |

| Reducing Vulnerabilities |

7

Address and reduce vulnerabilities in migration. 8

Save lives and establish coordinated international efforts on missing migrants. 9

Strengthen the transnational response to smuggling of migrants. |

10

Prevent, combat and eradicate trafficking in persons in the context of international migration. 14

Enhance consular protection, assistance and cooperation throughout the migration cycle. |

| Cooperation and Collaboration |

19

Create conditions for migrants and diasporas to fully contribute to sustainable development in all countries. 21

Cooperate in facilitating safe and dignified return and readmission, as well as sustainable reintegration. |

23

Strengthen international cooperation and global partnerships for safe, orderly and regular migration. |

Sources: Figure prepared by the authors based on information obtained from United Nations Refugees and Migrants, Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration ![]() (629 KB, 34 pages), 13 July 2018, para. 16, pp. 5–6. The 23 objectives have been categorized by the authors.

(629 KB, 34 pages), 13 July 2018, para. 16, pp. 5–6. The 23 objectives have been categorized by the authors.

The final sections of the GCM outline operational aspects that contribute to implementing, following up and reviewing progress on the 23 objectives. Assistance to enable states to implement the objectives is provided for through a UN‑based mechanism that promotes knowledge sharing among “Member States, the United Nations and other relevant stakeholders, including the private sector and philanthropic foundations.”26 The mechanism also includes a start‑up fund to both receive funding and provide financing for capacity‑building projects.

The UN Network on Migration, established to “ensure effective, timely and coordinated system‑wide support to Member States” implementing the GCM, is also singled out as playing a role.27 The importance of continuing global, regional and sub‑regional dialogues on migration is noted,28 as is a biennial report on the progress of the implementation of the GCM from the Secretary‑General to the UNGA.29

Aspects of follow‑up and review include repurposing the High‑Level Dialogue on International Migration and Development, currently scheduled to take place every fourth session of the UNGA, to review the implementation of the GCM. Renamed the “International Migration Review Forum,” the forum will discuss “the implementation of the Global Compact at the local, national, regional and global levels, as well as allow for interaction with other relevant stakeholders with a view to building upon accomplishments and identifying opportunities for further cooperation.”30

Finally, once again recognizing state sovereignty, the GCM’s implementation section notes that the agreement should be executed “taking into account different national realities, capacities, and levels of development, and respecting national policies and priorities.”31

The fundamental principles and concepts at the heart of both global compacts are not new to Canada. The Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship, Mr. Matt DeCourcey, has stated that Canada’s immigration system aligns with both the global compacts’ objectives and commitments.32 Referring specifically to the GCM, the Government of Canada underlined that “the majority of the almost 200 action items listed under the Compact’s objectives reflect current Canadian practices.”33

Canada’s immigration and refugee framework is shaped by the Constitution Act, 186734 and the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms35 (Charter), with its main obligations and objectives set out in the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act36 (IRPA). Through this framework, Canada can

To meet its immigration and refugee objectives and to maintain a managed and planned immigration system, the federal government establishes policies and programs in areas such as the following:

Also, in consultation with provinces and territories, which share jurisdictional responsibility for immigration, the federal government decides how many immigrants will be accepted in a given year. These targets are set out in the multi‑year Immigration Levels Plan.40 The Immigration Levels Plan (formerly the Annual Levels Plan) “not only determines how resources of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada … are allocated but also reveals the government’s vision for the role of immigration in Canadian society.”41

Canada works towards effective socio‑economic integration of newcomers to address labour shortages. Across the country, more than 500 settlement organizations provide services, such as language training, in partnership with federal, provincial and municipal governments, to integrate newcomers in Canadian society and help them join the job market. These settlement services are also adapted to the needs of specific groups of newcomers, such as children and youth, who can access the Settlement Workers in Schools programs.42

Canada’s immigration policy facilitates family reunification for people through the Family Class Sponsorship Program, as well as other programs, such as family reunification for protected persons. Immigration to Canada as a member of the family class depends on the relationship between the foreign national – spouse, common‑law partner, child, parent – and the sponsor, who must be either a Canadian citizen or a permanent resident.

In terms of refugee protection and complementary pathways for refugees, Canada has significant expertise with the private sponsorship of refugees,43 such as occurred with the resettled Syrian refugees in 201544 and the resettled survivors of Daesh in 2017 and 2018. Since 2016, Canada has worked with over 15 countries interested in adopting similar sponsorship programs tailored to their reality.45 The Global Refugee Sponsorship Initiative is led by the Government of Canada, the Office of the UNHCR, the Giustra Foundation, the Open Society Foundations and the University of Ottawa Refugee Hub. The initiative is designed to provide training and advice to countries interested in offering refugee resettlement through community sponsorship. The goal is to mobilize citizens and create alternate pathways for admission of refugees.46

Canadian federal laws and policies with respect to multiculturalism also facilitate the integration of newcomers. The Charter recognizes the importance of preserving and enhancing the multicultural heritage of Canadians.47 In addition, the 1988 Canadian Multiculturalism Act seeks to preserve and enhance Canada’s diverse cultural heritage and to recognize it as a fundamental characteristic of Canadian society, while ensuring the equality and full participation of all Canadians in the country’s social, political and economic spheres.48 Canada’s approach to multiculturalism encourages integration by allowing immigrants to fully participate in Canadian society while also preserving their cultural heritage.49

Canada’s immigration laws, policies and programs provide examples of how the principles of the global compacts can be interpreted and applied, which reflect the variety of tools governments have at their disposal to work towards the objectives of the global compacts. Moreover, Canada’s participation at high‑level officials’ meetings, the Global Refugee Forum and the International Migration Review will allow the federal government to share best practices with and learn from other states.50

† Library of Parliament Background Papers provide in‑depth studies of policy issues. They feature historical background, current information and references, and many anticipate the emergence of the issues they examine. They are prepared by the Parliamentary Information and Research Service, which carries out research for and provides information and analysis to parliamentarians and Senate and House of Commons committees and parliamentary associations in an objective, impartial manner. [ Return to text ]

any person who is moving or has moved across an international border or within a State away from his/her habitual place of residence, regardless of (1) the person’s legal status; (2) whether the movement is voluntary or involuntary; (3) what the causes for the movement are; or (4) what the length of the stay is.

See IOM, “Migrant,” Key Migration Terms. [ Return to text ]

on the margins of the General Assembly, on 20 September 2016, the United States President Obama hosted the Leaders’ Summit on Refugees, alongside co‑hosts Canada, Ethiopia, Germany, Jordan, Mexico and Sweden, which appealed to governments to pledge significant new commitments on refugees.

See also UN, “UN Summit for Refugees and Migrants 2016,” Refugees and Migrants. [ Return to text ]

© Library of Parliament