Sanctions are measures implemented by governments to restrict or prohibit certain types of interactions with a foreign state, individual or entity. Governments impose sanctions in pursuit of foreign policy objectives, most often in response to breaches of international peace and security, but also in cases of gross violations of human rights and significant acts of corruption. Over the last 30 years, the use of sanctions by the United Nations (UN), Canada and allies such as the United States (U.S.) and the European Union (EU) has increased significantly.

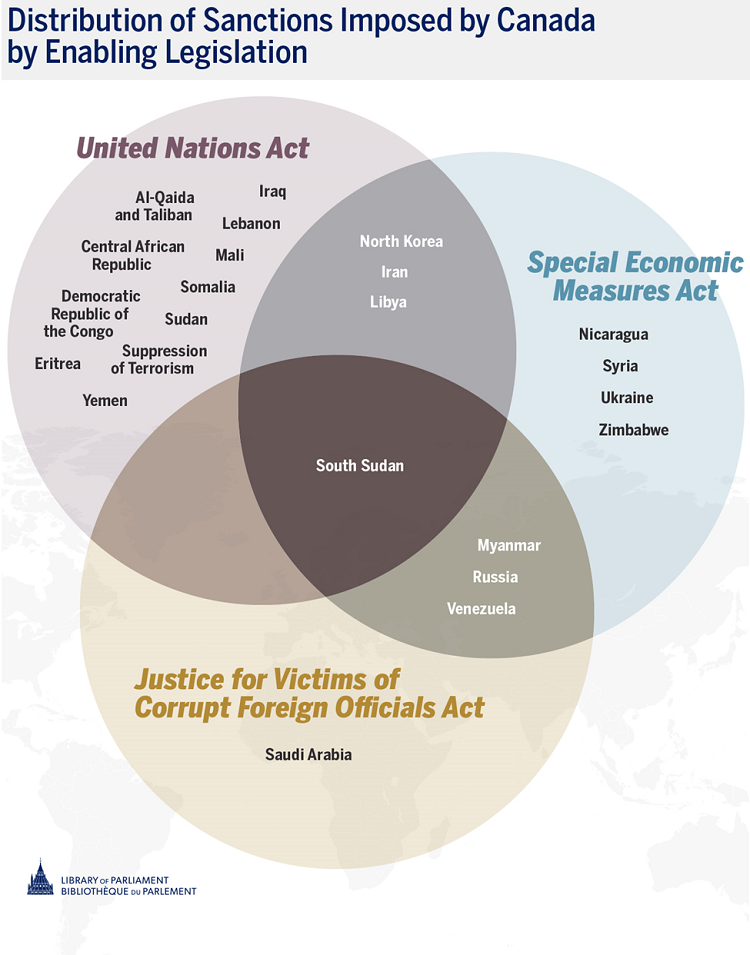

Canada imposes UN-mandated sanctions through the United Nations Act, and autonomous sanctions through the Special Economic Measures Act and the Justice for Victims of Corrupt Foreign Officials Act (Sergei Magnitsky Law). Regulations made under these Acts create a series of restrictions, prohibitions and obligations applicable to firms and people in Canada and to Canadians overseas in relation to foreign states, individuals and entities. The Acts include criminal penalties for contravening the regulations and provisions for parliamentary reporting and review. Canada currently has 20 sanctions regimes targeting specific countries and two transnational regimes related to counter-terrorism, as well as human rights and corruption sanctions targeting 70 individuals from five countries.

Canada often imposes sanctions in coordination with its allies, most notably the U.S. and the EU. That said, Canadian sanctions practice differs from that of the U.S. in a number of important respects. Unlike Canada, the U.S. imposes so-called “secondary sanctions,” which seek to impose restrictions on firms in third-party countries. The U.S. also regularly imposes large fines in response to the violation of sanctions, totalling more than US$1 billion in 2019.

The term “sanctions,” or economic sanctions, is used to describe a range of measures that can be implemented by governments to restrict or prohibit certain types of interactions with a foreign state, individual or entity. Possible measures range from sanctions targeted against specific individuals to broad economic embargoes. Sanctions are intended to be temporary, implemented to achieve a specific foreign policy objective, yet they often remain in place for many years.

Sanctions are not a singular tool. A basket of measures are often implemented together, in what is referred to as a sanctions regime. Such regimes are usually implemented in reference to a specific country but may also be thematic in nature and have transnational application, such as sanctions related to international terrorism.

Though the targets of sanctions are foreign actors, the obligations and prohibitions put in place by the measures are generally applied to domestic actors. That is, sanctions do not directly punish their targets, they instead create a cost for them by prohibiting or limiting the ability of others to interact with them. Since they restrict commercial activity and create obligations for firms, sanctions also place costs on the domestic private sector in implementing states. Affected firms incur expenses to ensure compliance and may potentially forego business opportunities.

Sanctions allow governments to respond to international behaviour that is determined to be adverse to their national interests, including violations of international law and norms. The overall intent is to affect or constrain the target’s behaviour or to communicate the unacceptability of that behaviour.1

In the past, sanctions were primarily enacted in response to breaches of international peace and security, including armed conflict. Increasingly, they are also being imposed in cases involving gross violations of human rights and serious acts of corruption. Sanctions may be implemented multilaterally, most commonly through the United Nations (UN) Security Council, or regionally, via decisions taken by regional organizations (e.g., the Organization of American States). Alternatively, they may be implemented autonomously based on the foreign policy decisions and domestic legislation of individual states. Autonomous sanctions can also be of an informal multilateral nature, as like-minded countries often coordinate their actions.

Sanctions regimes may include both multilateral and autonomous sanctions. In cases where sanctions have been imposed multilaterally, states may decide to also impose autonomous sanctions when it is determined that multilateral measures are insufficiently strict or too narrow. This layering can complicate compliance efforts by the private sector, by requiring compliance with multiple pieces of legislation.

Sanctions are one of many foreign policy tools available to states and are often implemented in conjunction with other measures (e.g., diplomatic pressure; security assistance). An inherently coercive tool that seeks to impose costs on their targets, sanctions are seen as a more robust response to international events than diplomacy alone, while being less aggressive than the use of force. The middle-ground nature of sanctions – along with the perception that they entail a relatively low cost of implementation and low risk of escalation – helps to explain their increasing popularity in recent decades.2 Between 1945 and 1990, the UN Security Council used its sanctions authority in only two cases, both instances being a response to racist regimes, in South Africa and Southern Rhodesia respectively. In the 30 years since, the Security Council has put in place 28 international sanctions regimes, 14 of which are active today.3

There has been a similar expansion in the use of autonomous sanctions. In Canada, legislative authority to impose autonomous sanctions was created in 1992 with the enactment of the Special Economic Measures Act (SEMA) and was first used to impose sanctions against Haiti.4 Canada currently imposes autonomous sanctions on 11 countries, generally in coordination with its allies the United States (U.S.) and/or the European Union (EU).5

The growing popularity of sanctions in international affairs has not been without criticism. Along with questions about their effectiveness, critics have raised concerns about the humanitarian impact of sanctions. Cases such as the humanitarian crisis in Iraq in the 1990s, due in part to an economic embargo imposed by the UN, motivated a shift towards targeted sanctions in the 2000s.6 Current state practice, however, continues to employ a combination of targeted and broad-based measures, which can have humanitarian consequences.

When determining whether sanctions are an appropriate tool, and in evaluating their effectiveness, it is important to identify the purpose of sanctions regimes. They generally can be understood as aiming to achieve one or more of the following outcomes:

In practice, sanctions are usually enacted with the intent of achieving multiple purposes. Non-proliferation sanctions, for example, seek to both coerce and constrain targets in their pursuit of nuclear weapons capability. Sanctions in the case of human rights violations seek to stigmatize the individual(s) in question and to restrict their ability to travel and to access legitimate financial institutions.

Different types of sanctions can be broadly categorized based on the scope of their application. They range from measures that impose restrictions on specific individuals and entities to those targeting a specific sector of the economy, to full embargoes limiting most or all economic interaction with a country. Sanctions measures are generally seen as falling within one of these three groups:

The Government of Canada imposes sanctions through the regulatory authority granted to it by three Acts:

Regulations made by the Governor in Council pursuant to these three Acts place prohibitions and restrictions on individuals and entities in Canada and on Canadian citizens overseas.

The three statutes set out the circumstances under which the government may impose sanctions. These provisions limit government discretion to impose sanctions, as described in Table 1 below:

| - | United Nations Act | Special Economic Measures Act | Justice for Victims of Corrupt Foreign Officials Act (Sergei Magnitsky Law) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Qualifying circumstances |

|

|

|

Source: Table prepared by the author based on information obtained from United Nations Act, R.S.C. 1985, c. U-2, s. 2; Special Economic Measures Act, S.C. 1992, c. 17, s. 4(1.1); and Justice for Victims of Corrupt Foreign Officials Act (Sergei Magnitsky Law), S.C. 2017, c. 21, s. 4(2).

While similar, the human rights and corruption criteria under the JVCFOA and the SEMA differ in relation to their scope and applicability. The criteria under the JVCFOA are tied to the actions of individual foreign nationals, while the SEMA’s criteria relate to broader circumstances in a foreign state. The situation in a given country may satisfy criteria under different Acts. For example, sanctions under all three Acts are currently in place with regard to South Sudan.10

The three Acts described above also define the restrictions and prohibitions that can be implemented once the criteria for sanctions have been met. Under the SEMA, regulations can require the seizure, freezing or sequestration of property, as well as the restriction or prohibition of property transactions, export or import of goods, transfer of technical data, provision of financial services and the docking of ships or landing of aircraft. Those measures can be applied in relation to the state in question, its citizens or specified individuals or entities within the state.11

With the exception of provisions relating to aircraft and ships, the JVCFOA contains a similar set of possible prohibitions and restrictions.12 However, unlike the SEMA, the measures can only be made in reference to designated foreign nationals. The UNA does not list the measures that can be imposed. Instead, it limits measures to those necessary for or expedient to the enforcement of UN Security Council decisions.13 Specific measures are outlined in the regulations.

The JVCFOA, as well as many regulations made pursuant to the SEMA and the UNA, contain impose a duty to determine on certain types of financial and insurance institutions.14 Under these provisions, banks and other listed institutions are required to monitor on a continuing basis whether they are in the possession or control of property subject to a sanctions measure and to report any such property to designated government authorities.

All three Acts include a criminal offence for contravening or failing to comply with sanctions regulations, which in all three cases is a hybrid offence, allowing violators to be charged with either a summary conviction or an indictable offence.15 For the JVCFOA and SEMA, indictable offences carry a maximum term of five years’ imprisonment; for the UNA, the maximum is 10 years.

The JVCFOA and regulations under the SEMA also contain provisions that allow persons targeted by sanctions to challenge their inclusion in the relevant schedule, or list. Listed persons may apply to the Minister of Foreign Affairs for removal. Once an application has been received, the Minister must then determine if reasonable grounds exist to recommend delisting.16 The UNA does not include a similar provision, as the lists of individuals and entities are established by the UN, which has its own delisting process.17

All three Acts require that regulations or orders made pursuant to their provisions be tabled in Parliament. The UNA also includes a provision that allows regulations to be annulled within 40 days of their tabling through a resolution from both Houses of Parliament (the Senate and the House of Commons).18 Similarly, the SEMA allows for regulations to be revoked or amended pursuant to a motion adopted in both Houses.19 In addition to these actions, which apply to individual regulations, the JVCFOA requires that committees in both Houses conduct a “comprehensive review” of its operation and that of the SEMA within five years of the JVCFOA coming into force. Furthermore, either House is allowed to establish or designate a committee to review the JVCFOA sanctions list and make recommendations as to whether listed persons should be maintained or removed.20

While the three Acts discussed above form the core of Canada’s economic sanctions, other legislation plays a complementary role or can have a similar effect.

UN sanctions regimes often include so-called “travel bans,” restricting listed persons from entering or travelling through UN member states. In Canada, these measures are implemented through the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act.21 Under the Act, a foreign national or Canadian permanent resident can be deemed inadmissible to Canada if they are subject to sanctions imposed by an international organization or association of which Canada is a member.22 Foreign nationals and Canadian permanent residents can also be deemed inadmissible if they are listed under JVCFOA or SEMA regulations enacted pursuant to their human rights and corruption criteria.23

The Export and Import Permits Act provides the federal government with the authority to control aspects of Canada’s international trade, including restrictions similar to those found in sanctions measures.24 Export restrictions under the Act are generally based on the type of good being exported and cover the export of weapons and military equipment, related technical information and dual-use goods. The Act also allows for the control of trade based on the country of destination, including through the Area Control List, a regulation made pursuant to the Act.25 All exports to countries named on the control list require prior authorization by the Minister of Foreign Affairs. North Korea, which is also subject to sanctions under the SEMA and UNA, is currently the only listed country.

The Government of Canada addresses the threat posed by international terrorism both through the Criminal Code (Code) and regulations under the UNA.26 Among the Code’s terrorism provisions are sanctions-like measures that grant the government authority to create a list of prohibited terrorist groups and to freeze or seize related property.27 The Code also contains duty to determine obligations for financial and insurance institutions similar to those found in sanctions regulations.28

Canada currently has sanctions regimes targeting 20 countries under the UNA and SEMA. There are also two transnational counterterrorism regimes under the UNA. Additionally, 70 foreign nationals from five countries are sanctioned under the JVCFOA.29 Figures 1 and 2 show Canada’s sanctions regimes by geographic distribution and their enabling legislation.

Figure 1 – Geographic Distribution of Canadian Sanctions Regimes

Source: Figure prepared by Library of Parliament using data obtained from Government of Canada, Canadian sanctions legislation.

Figure 2 – Canadian Sanctions Regimes by Enabling Legislation

Source: Figure prepared by Library of Parliament using data obtained from Government of Canada, Canadian sanctions legislation.

The Charter of the United Nations grants the UN Security Council authority to apply sanctions measures in response to “any threat to the peace, breach of the peace, or act of aggression.”30 Resolutions implementing or modifying sanctions regimes are passed through a majority vote of the council’s 15 members, subject to a veto by one of its five permanent members: China, France, Russia, the United Kingdom (U.K.) and the U.S.

When the UN Security Council establishes a new sanctions regime, it generally creates a subsidiary committee of the council to oversee implementation and monitor compliance.31 These sanctions committees are often also granted authority to add and remove individuals and entities from targeted sanctions lists and are usually assisted in their work by a panel of experts.

Partly in response to successful legal challenges in Europe and elsewhere, the UN Security Council has developed a system by which targeted individuals or entities can challenge their listing in sanctions regimes.32 For measures implemented through the Da’esh and Al-Qaida sanctions regime, an independent ombudsperson was created in 2010 to provide the council with impartial recommendations on requests for removal from sanctions lists.33 Removal requests for all other sanctions regimes can be submitted through a focal point for delisting, which facilitates consideration of the request by the relevant sanctions committee and national governments but does not provide recommendations.34 The council also publishes narrative summaries that provide brief explanations for why an individual or entity has been targeted.35

Like Canada, the EU imposes sanctions pursuant to UN Security Council decisions and autonomously through European law.36 The decision to impose autonomous sanctions is taken by the Council of the European Union; measures are either implemented directly through EU regulations or they create an obligation for member states to pursue implementation. While EU Council decisions are binding on member states, those states may also impose sanctions autonomously through their own domestic legislation.

EU guidelines set out a number of principles by which measures should be designed and implemented.37 According to these guidelines, EU sanctions should be targeted measures imposed on “those identified as responsible for the policies or action,” that prompted the sanctions. Measures must conform with international law, including human rights law and multilateral trade obligations.38 The guidelines also recognize the need to respect the right to due process and effective remedy, requiring clear criteria to be set out in EU Council decisions for the listing of persons and the provision of a statement of reasons for the listing of each target.

U.S. sanctions programs differ from other jurisdictions in several important respects. For one, the scope of U.S. sanctions programs is significantly larger than it is for the programs of other jurisdictions. For example, the UN currently lists around 1,000 individuals and entities through its targeted sanctions. In addition to those, Canada targets more than 1,300 others under the SEMA and JVCFOA.39 The EU’s consolidated list, which includes UN sanctions, totals 2,200 entries.40 By comparison, the U.S. consolidated list exceeds 7,900 targets.41

Unlike in other jurisdictions, where the decision to impose sanctions is generally the prerogative of the executive branch of government, both the U.S. executive and legislative branches are active in sanctions decisions. Similar to other jurisdictions, the U.S. has enabling legislation that allows the executive branch to impose sanctions under certain circumstances.42 However, the U.S. Congress also has a history of passing detailed legislation, imposing specific measures in response to particular international events. A recent example of such legislation is the Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act of 2017, which made a number of changes to sanctions regimes targeting Iran, North Korea and Russia.43

The U.S. also extends the reach of some of its sanctions regimes by creating obligations on foreign entities. So-called “secondary sanctions” oblige firms and individuals in third-party countries to abide by U.S. sanctions restrictions or risk losing access to the U.S. financial system, including U.S. dollar-based transactions. The re-imposition of U.S. autonomous sanctions against Iran in 2018, following the U.S. withdrawal from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), is an example of the U.S. imposing sanctions that placed restrictions on foreign firms in third-party countries. The JCPOA had been negotiated by the U.S., Iran, China, France, Germany, Russia, the U.K. and the High Representative of the EU, and then endorsed in Resolution 2231 (2015) by the UN Security Council.44 The U.S. autonomous sanctions thus proved somewhat controversial internationally, as they did not align with the foreign policy of other states whose firms nonetheless had little effective choice but to abide by the measures.45

Through the Foreign Extraterritorial Measures Act, the Government of Canada has taken steps to protect Canadian companies from U.S. secondary sanctions targeting Cuba.46 The Act prohibits Canadian companies from complying with certain U.S. sanctions against Cuba and to report to Canada’s Attorney General any communications received in respect of such measures.47 The exact legal effect of these provisions varies, but experts recommend that Canadian companies doing business with Cuba be aware of their compliance obligations in both countries.48

U.S. sanctions programs also differ from other jurisdictions in terms of the level of enforcement. Due in part to the larger scope of its programs and the centrality of the U.S. within the international financial system, the U.S. dedicates a significant amount of resources to enforcing sanctions, including through a dedicated agency – the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) – within the Department of the Treasury.49 Enforcement efforts in the U.S. have led to the imposition of large fines against violators. In 2019, OFAC civil penalties exceeded US$1.29 billion across 26 separate penalty or settlement decisions.50

† Library of Parliament Background Papers provide in-depth studies of policy issues. They feature historical background, current information and references, and many anticipate the emergence of the issues they examine. They are prepared by the Parliamentary Information and Research Service, which carries out research for and provides information and analysis to parliamentarians and Senate and House of Commons committees and parliamentary associations in an objective, impartial manner. [ Return to text ]

© Library of Parliament