Food insecurity is generally defined as a situation that exists when people lack secure access to sufficient amounts of safe and nutritious food. In recent years, rates of household food insecurity have risen in Canada; the situation is disproportionately worse in the North than elsewhere in the country, with rates of household food insecurity reaching 21.8% in the Yukon, 34.2% in the Northwest Territories and 58.1%, in Nunavut, according to Statistics Canada data for 2023.

Among Northerners, Indigenous peoples are particularly at risk of being food insecure. The high rates of food insecurity among northern and Indigenous populations can be explained by several factors, such as the relative remoteness and isolation of their communities, financial hardship and socio-economic inequities, the legacy of colonial policies, climate change, and environmental dispossession and contamination. Food insecurity has severe consequences for health and well-being; for instance, it has been linked to malnutrition, infections, chronic diseases, obesity, distress, social exclusion, depression and suicidal ideation.

By providing a subsidy to eligible retailers, suppliers and local producers in remote and isolated communities, Nutrition North Canada, a federal food subsidy program, targets one cause of food insecurity: the high cost of nutritious food in the North. Introduced in 2011, the program has been criticized over the years, with critics noting that the cost of nutritious food in the North remains too high for too many families. As of March 2021, the average cost of a healthy diet to feed a family of four in the North was $419.11 per week (down by 1.73%, or $7.37, since the program’s inception in 2011). Over the years, the federal government has made significant changes to address program shortcomings.

Local, regional, provincial and territorial initiatives have also been implemented to address food insecurity in the North. These include a wide range of measures, from culturally appropriate food guides to comprehensive poverty-reduction initiatives. Communities have their own solutions, from food banks and soup kitchens to hunting and harvesting support programs. In 2021, Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami – a national organization that advocates for the rights and interests of Inuit in Canada – released its Inuit Nunangat Food Security Strategy to address the problem.

Food insecurity is a serious public health issue that has worsened in recent years. To reduce food insecurity in the North, the Government of Canada and its partners will need to address its social, economic and environmental roots.

In Canada, at least 10 million individuals were food insecure in 2024, according to Statistics Canada; however, this data does not take into account people who live on First Nations reserves, in some remote areas and in the territories.1 Yet, due to several factors, Northerners – in particular, women, children and Indigenous peoples – are more at risk of experiencing food insecurity than are people living elsewhere in the country. The situation has a substantial impact on their health and well-being.2

This paper provides a brief overview of the factors that contribute to food insecurity in northern Canada3 and the resulting consequences. Additionally, it looks at initiatives that directly or indirectly address this issue.

Food security is defined by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations as a “situation that exists when all people, at all times, have physical, social and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life.”4 Conversely, food insecurity is defined as a “situation that exists when people lack secure access to sufficient amounts of safe and nutritious food for normal growth and development and an active and healthy life.”5

Some researchers have argued that these broad definitions of food security and insecurity may not fully address considerations that are unique to Indigenous peoples, such as the place of food in their cultures, identities and ceremonies, as well as the nutritional and socio-cultural value of country or traditional foods.6 Others have proposed to define food security as “a condition where all community residents obtain a safe, culturally acceptable, nutritionally adequate diet through a sustainable food system that maximizes community self-reliance and social justice.”7

Indigenous-led initiatives, such as the First Nations Food, Nutrition and Environment Study and the Inuit Nunangat Food Security Strategy, have adopted the FAO definition of food security. Both initiatives apply this definition to the unique circumstances that First Nations and Inuit face. Both also emphasize the importance of traditional food systems for Indigenous food security.

Statistics Canada collects data on household food insecurity through tools like the Household Food Security Survey Module of the Canadian Community Health Survey and the Canadian Income Survey (CIS). The most recent CIS data is from 2023 and indicates the following rates of household food insecurity in the territories:

Among Northerners, Indigenous peoples are particularly at risk of being food insecure. In 2012, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the right to food reported that Inuit of Nunavut had “the highest documented food insecurity rate for any [A]boriginal population in a developed country.”9 Across Inuit Nunangat (the area covering the land, water and ice of the Inuit homeland in Canada), the rate of food insecurity among Inuit aged 25 and over was 52% in that year.10 The Special Rapporteur also expressed concerns about Canada’s efforts: “Canada’s record on civil and political rights has been impressive. Its protection of economic and social rights, including the right to food, has been less exemplary.”11

A 2014 report by the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the rights of Indigenous peoples indicated that, despite some improvements, the socio-economic conditions of Indigenous peoples in Canada remained “distressing.”12 A report in 2023 by another Special Rapporteur on the rights of Indigenous peoples stated that “[t]he socioeconomic situation of Indigenous Peoples in Canada has not significantly improved since previous reports under the mandate.”13

Similarly, rates of food insecurity are higher in First Nations communities compared with the rest of Canada. According to the First Nations Food, Nutrition and Environment Study, which collected data from 2008 to 2016 in 92 randomly selected First Nations south of the 60th parallel,

[t]he prevalence of food insecurity is very high in First Nations communities (48%) [with] rates [being] also significantly higher in remote communities with no year-round road access to a service centre (58%).14

Several Métis communities are located in what is considered the North. However, it is more difficult to be precise about the situation of the Métis, as peer reviewed data about their experience of food insecurity in the North are limited.15

Several interconnected factors contribute to food insecurity in the North. The relative remoteness and isolation of northern communities contribute to a high cost of living, coupled with high costs to ship and store nutritious food. Another important factor that contributes to food insecurity is socio-economic status. Research shows that poverty, financial hardship, unemployment or underemployment, low income and low educational attainment contribute to food insecurity.16 In Canada, First Nations, Inuit and Métis populations generally have a lower socio economic status than non Indigenous Canadians.17

Indigenous peoples are also particularly at risk of experiencing food insecurity due to the long-lasting and ongoing effects of colonial policies – including forced relocations and residential schools – that disrupted their relation to the land and to their traditional food systems.18 These policies also negatively affected the intergenerational knowledge transfer of harvesting and hunting skills, and of healthy eating habits.19 Access to and consumption of traditional foods is further affected by environmental dispossession (that is, diminished access by Indigenous peoples to the resources of their traditional lands), climate change and the presence of contaminants in the environment.20

The far-reaching consequences of food insecurity can have negative effects on the physical and mental health of both children and adults. Among other things, food insecurity has been associated with malnutrition, infections, chronic diseases and obesity, as well as distress, social exclusion, depression, suicidal ideation and suicide attempts.21 Some researchers have identified food insecurity as the “largest [contributor] to the concentration of psychological distress and suicidal behaviours among low-income Indigenous peoples in Canada.”22 In the case of children, hunger caused by food insecurity has been found to have a negative impact on the ability to learn, thus contributing to poor educational outcomes.23

Indigenous peoples in Canada’s North have also been experiencing changes in their dietary habits.24 The transition from nutritious, traditional diets to store-bought processed foods has been found to potentially “increase the risk for diet-sensitive chronic diseases and micronutrient deficiencies in Aboriginal communities.”25

Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami (ITK), the national organization that advocates for the rights and interests of Inuit in Canada, notes that food insecurity is not only a threat to public health, but also to “overall social and cultural stability in Inuit communities.”26

The right to food – whereby everyone should have regular access to sufficient safe and nutritious food to live a healthy and active life – is recognized as a human right by international instruments that apply to Canada, such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.27 Nevertheless, Canada has yet to create an enforceable right to food in domestic law.

As noted by the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the right to food following an official visit to Canada in 2012:

As a party to the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, the Convention on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women, and the Convention on the Rights of the Child, Canada has a duty to respect, protect and fulfil the right to food. Yet, Canada does not currently afford constitutional or legal protection of the right to food. The 1982 Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms protects a number of civil and political rights, but has no substantive provisions protecting social and economic rights, broadly, and the right to food, more specifically. While section 7 (protecting the right to life, liberty and security of the person) and section 15 (guaranteeing the right to equality before and under the law) provide avenues for the protection of the right to food, and the judiciary has repeatedly affirmed that international human rights norms constitute persuasive sources for constitutional and statutory interpretation, case law has yet to recognize explicitly the right to food.28

Moreover, while it does not touch on the right to food explicitly, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) contains key articles that relate to food as a collective right of Indigenous peoples, including:

In 2021, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act30 came into force, affirming that the UNDRIP has application in Canadian law. The Act provides a framework for the federal government to ensure that its laws are consistent with the UNDRIP. Canada’s 2023–2028 action plan for implementing this Act highlights measures related to food security and sovereignty. For instance, the Government of Canada is committed to

support[ing] the right of Indigenous peoples to self-determination and food sovereignty according to their own priorities through the provision of long-term and flexible funding to strengthen access to traditional foods and local food systems.31

Canada has traditionally addressed the right to food through policy and programs, such as The Food Policy for Canada (launched in 2019) and Canada’s National Pathways32 to sustainable food systems (launched after the United Nations Food Systems Summit in 2021). The Government of Canada continues to be guided by the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, notably Sustainable Development Goal 2 which aims to end hunger, achieve food security and improve nutrition by 2030.33

At the provincial, territorial, regional and local levels, efforts have been made to address the causes of food insecurity and mitigate its consequences. For its part, the federal government is playing a role through its Nutrition North Canada (NNC) program34 which provides subsidies and grants to improve access to nutritious and traditional food in certain communities. When it was created in 2011, reducing food insecurity was not part of NNC’s mandate. Rather, the program targeted one cause of food insecurity: the high cost of nutritious food in the North. Following Budget 2021, NNC’s mandate was expanded and the program now aims to strengthen food security in eligible communities.35

Moreover, the 2019 Food Policy for Canada: Everyone at the Table (the Food Policy) sets out a vision in which “[a]ll people in Canada are able to access a sufficient amount of safe, nutritious, and culturally diverse food.”36

The Food Policy identifies four areas for short- and medium-term actions, one of which is the need to support food security in northern and Indigenous communities.37 The development of a national food policy has been described as “a critical opportunity to address food insecurity,” in part because of the need for coordination among several federal departments and agencies along with other levels of government.38

In 2024, the federal government also presented the country’s first national school food program. The National School Food Policy, which provides the overarching vision and guidelines for the program,

builds on and aligns with Canada’s international commitments through its membership in the Global School Meals Coalition and enactment of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act.39

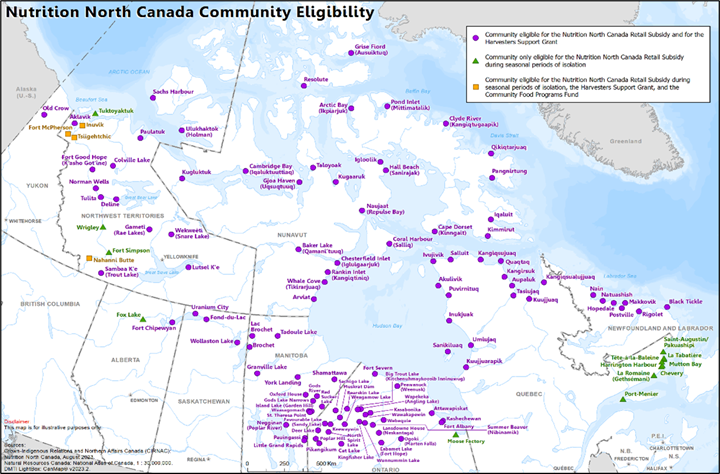

NNC aims to improve access to nutritious food and to certain essential non-food items in northern communities that lack year-round ground access. Figure 1 shows all of the communities eligible for NNC subsidies.40

Figure 1 – Nutrition North Canada Eligible Communities as of February 2024

Source: Government of Canada, Eligible communities.

To be eligible, communities must also meet the territorial or provincial definition of a northern community, have an airport, post office or grocery store, and have a year round population. Some communities are only eligible during seasonal periods of isolation.41 The three subsidy levels – high, medium and low – depend on the following factors:

The program’s main objective has always been to offset the “inherent disadvantage faced by isolated northern communities which have no other option but to fly in perishable foods.”43 In 2011, NNC replaced the Food Mail Program (also known as the Northern Air Stage Program), which had subsidized the cost of shipping food to eligible northern and isolated communities since the 1960s.

Whereas the Food Mail Program subsidized the transportation of food, NNC offers a subsidy to registered retailers, suppliers, country food processors and local food growers, who must then pass the full savings on to consumers. Food banks and charitable organizations can now also access the subsidy to reduce the cost of donating food to isolated communities.44

The NNC subsidy is applied to a list of eligible nutritious foods and essential non food items, such as diapers, soap and personal hygiene products, to help offset the high cost of living in isolated northern communities (see Appendix A). It should be noted that the list of eligible food and non-food items is updated periodically. NNC also provides funding for nutrition education initiatives,45 though these activities only account for a small portion of the program’s annual budget.

The federal government has made several changes to NNC in recent years by adding support for traditional food systems through the Harvesters Support Grant to lower the costs associated with traditional hunting and harvesting activities, the Community Food Programs Fund to support food-sharing activities and the Food Security Research Grant to support Indigenous-led research.46 The list of subsidized products was revised in 2019–2020, then again in 2020–2021, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.47

The government has also committed additional funding for the program in recent budgets, although any funding commitment needs to be approved by Parliament through the estimates process, since the program has no legislative basis:

Additionally, the government periodically reassesses eligibility criteria and community needs in order to determine whether to expand the program. As of February 2025, 124 communities were eligible for the program; 112 of them were also eligible for the Harvesters Support Grant because they are reliant on air transportation for more than eight months per year.51

In 2022, the program was expanded to also include non-profits, such as food banks, and local food producers. The previous year, the House of Commons Standing Committee on Indigenous and Northern Affairs had recommended making the program available to community organizations, cooperatives and non-profits.52

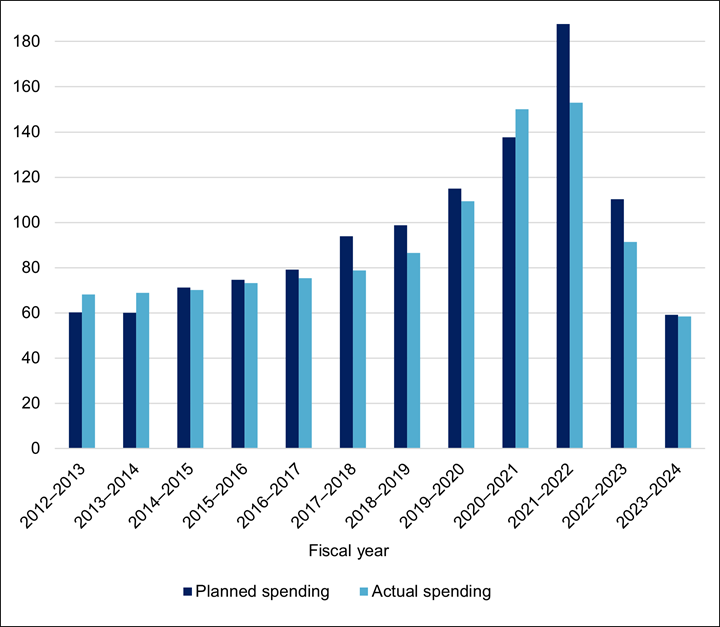

As a cost containment measure, NNC’s annual budget was initially fixed at $60 million in 2011. However, in subsequent years, the federal government committed to enhancing the program and increased its funding. A compound annual escalator of 5% was also added to the food subsidy budget in 2014 to account for growing demand and population growth.53 As a result, planned program spending increased steadily in the program’s early years, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2 – Nutrition North Canada Annual Spending, 2012–2013 to 2023–2024 ($ millions)

Sources: Figure prepared by the Library of Parliament using data obtained from Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada, Departmental Plans and Results Reports; and Government of Canada, Departmental Plans and Results for Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada.

NNC went over its budget by 12.9% in 2012–2013 and 14.6% in 2013–2014. These variances were attributed “to growth in demand for subsidized food” and changes to the subsidy rate in the program’s first year.54 According to the Office of the Auditor General of Canada (OAG), the department responsible for NNC at the time, Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada (AANDC), had to transfer funds away from other programs and activities to cover these variances.55 The trend gradually reversed and the program spent 12.4% less ($12.2 million) than planned in 2018–2019. Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada (CIRNAC), which succeeded AANDC as the lead department for NNC, explained that the variance between planned and actual spending in 2018–2019 was “due to a late implementation of program updates announced in December 2018.”56 Notwithstanding these variances, actual program spending grew by 27% ($18.4 million) from 2012–2013 to 2018–2019.

According to CIRNAC, actual spending was higher than planned in 2020–2021 because of additional funding related to the COVID-19 pandemic.57 Planned and actual spending continued to grow rapidly until 2021–2022 because of the changes made to the program, notably in response to COVID, before returning to levels closer to historic trends starting in 2022–2023. For 2024–2025, the government plans to spend $134.4 million on the program.58

Most of the NNC subsidies are directed to for-profit businesses in the North, who in turn are expected to pass these subsidies on to consumers in the form of savings (that is, lower prices for eligible items). In 2014, the OAG concluded that AANDC

ha[d] not managed the Program to meet its objective of making healthy foods more accessible to residents of isolated northern communities [and] that the Department ha[d] not done the work necessary to verify that the northern retailers are passing on the full subsidy to consumers.59

The NNC Advisory Board, tasked with providing Northerners with a direct voice in the program, noted similar concerns.60 Transparency has since improved; major retailers are required to display the savings resulting from NNC subsidies on store receipts since 1 April 2016.61 Moreover, all retailers must ensure the visibility and transparency of the program in their in store signage and communications.

NNC has also been criticized for its inadequate evidence base and accountability structure, its lack of responsiveness to concerns by community members and experts, and its failure to address inequities in food availability and affordability between regions and communities.62 Furthermore, a 2019 assessment of NNC “suggests that food insecurity … worsened in Nunavut communities after the introduction of the program.” According to the researchers who conducted the assessment, it “raises serious concerns about the federal government’s continued focus on food-subsidy initiatives to improve food access in the North.”63

In the Inuit Nunangat Food Security Strategy, ITK raises concerns that “the effects of the program on either food insecurity or economic development remain largely unknown because of limited transparency and the absence of rigorous evaluation.”64 Among other things, ITK recommended reforming NNC “into an evidence-based food security program.”65

In 2016, the federal government sought input from community members and stakeholders in the program. Despite participants being “largely appreciative of the program,” it was noted that “many families are [still] not able to afford healthy food” and that the “subsidy is not having a big enough effect on the price of food.”66 The program has been successful at maintaining stable prices; however, prices have not decreased significantly since it was implemented. From March 2011 to March 2021, the average weekly cost of the Revised Northern Food Basket decreased by only 1.73% (from $426.48 to $419.11).67

At a parliamentary hearing in May 2024, various retailers participating in the program highlighted further shortcomings. They noted that some costs associated with operating the subsidies are not covered by the program, that NNC does not address “the underlying inflationary issues that drive retail prices, such as fuel or cost of goods,” and that investments in the program have not kept pace with inflation. “As a result, its positive impact has eroded,” testified Dan McConnell, Chief Executive Officer of the North West Company, one of the major retailers participating in the program.68

In October 2024, the Minister of Northern Affairs announced that a Ministerial Special Representative would be appointed in early 2025 to conduct an external review of NNC; a final report is expected in 2026.69 In 2021, the House of Commons Standing Committee on Indigenous and Northern Affairs recommended launching a “full external evaluation” of NNC and modifying the program’s mandate to “improve food security outcomes in northern and isolated communities.”70

On 17 June 2019, the Minister of Agriculture and Agri-Food introduced the Food Policy for Canada. With a commitment of more than $134 million by the federal government, the stated aim of the Food Policy is to “shape a healthier and more prosperous future for Canadian families and communities.”71 The Food Policy is the result of consultations held in 2017, which outlined several priorities, such as:

The Food Policy also confirms the commitment made in Budget 2019 to allocate $15 million over five years, starting in 2019–2020, to create the Northern Isolated Community Initiatives Fund to support community-led food production projects.73 The Canadian Northern Economic Development Agency (CanNor) is responsible for this initiative.

Since then, CanNor has reported the following results:

Funded projects include a country food processing plant, hydroponic gardens, flour mill, food centre, infrastructure development, skills training and capacity building sessions and a research centre.

On 1 April 2024, the Prime Minister announced a new National School Food Program.75 In keeping with the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act passed in 2021, the federal government released the National School Food Policy on 20 June 2024 and laid out the foundation for the new program. According to the policy, the program is also consistent with Sustainable Development Goal 16 by aiming to “support Indigenous food sovereignty.”76

The National School Food Policy recognizes that some people, such as Indigenous people and those living in rural, remote or isolated areas, face barriers to accessing nutritious food; as a result, they are more seriously affected by food insecurity.

In a 2014 report, the Expert Panel on the State of Knowledge on Food Security in Northern Canada noted that “[l]ong-term alleviation of food insecurity requires drawing on the assets, talents, and abilities of northern communities.”77 These communities, alongside regional organizations and provincial/territorial governments, are already developing and implementing their own strategies and initiatives to address food insecurity in northern Canada.78

Examples of provincial, territorial and regional initiatives include the strategies and action plans developed by organizations such as the Nunavut Food Security Coalition,79 the culturally appropriate food guides prepared by the Nunavik Regional Board of Health and Social Services and the Department of Health of Nunavut,80 and comprehensive poverty-reduction initiatives, such as the Makimaniq Plan.81 Local community initiatives also offer short-term solutions to alleviate food insecurity (e.g., food banks and soup kitchens) and medium-term solutions (e.g., nutrition education and knowledge-sharing programs, and hunting and harvesting support programs).82

Given that each northern and Indigenous community has its own needs and circumstances, any sustainable solution to food insecurity must build on local knowledge and existing initiatives.

In July 2021, ITK published the Inuit Nunangat Food Security Strategy (INFSS) to advance “Inuit-driven solutions for improving food security and creating a sustainable food system in Inuit Nunangat.”83 The INFSS states that

[t]he high prevalence of food insecurity among Inuit is a complex national public health crisis that can only be remedied through coordinated actions undertaken by multiple partners. The drivers of food insecurity are interconnected.84

The INFSS has three main functions:

The INFSS identifies five priority areas for action to improve food security:

Food insecurity remains a serious public health and human rights issue in northern communities and among Indigenous peoples. To date, the federal government has yet to develop and implement a strategy to address the social, environmental and economic determinants of northern food insecurity in a holistic way. However, it has made changes to existing programs (such as NNC whose scope and mandate have been significantly expanded in recent years), and it has created new programs and policies with the goal of alleviating food insecurity among the people most at risk.

Food insecurity is rooted in complex issues, such as socio-economic gaps (notably, insufficient income and the high cost of living), climate change and the long-lasting and ongoing effects of colonialism. Consequently, addressing food insecurity in northern Canada will require a comprehensive, multi-faceted and coordinated approach that fully takes these issues into account. Any solution established to improve food security in the North will require the real engagement of local communities, including Indigenous peoples.

| Item Categories | High Subsidy | Medium Subsidy | Low Subsidy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vegetables and fruits | Frozen vegetables and fruits |

|

|

| Grain products |

|

|

|

| Milk and alternatives | Milk (fresh) |

|

|

| Other foods |

|

|

|

| Non-food Items |

|

|

Note: The items subsidized by Nutrition North Canada and the level of subsidy indicated in this table were current at the time of writing this HillStudy. The website was updated on 20 February 2025.

Source: Table prepared by the Library of Parliament using data obtained from Government of Canada, Eligible food and non-food items.

In Alberta, the following community is eligible for the Nutrition North Canada Retail Subsidy and for the Harvesters Support Grant: Fort Chipewyan. In addition, the community of Fox Lake is eligible for the Nutrition North Canada Retail Subsidy only during seasonal periods of isolation.

In Saskatchewan, the following three communities are eligible for the Nutrition North Canada Retail Subsidy and for the Harvesters Support Grant: Uranium City, Wollaston Lake and Fond-du-Lac.

In Manitoba, the following 16 communities are eligible for the Nutrition North Canada Retail Subsidy and for the Harvesters Support Grant: Tadoule Lake, Brochet, York Landing, Granville Lake, Shamattawa, Lac Brochet, Red Sucker Lake, Gods River, Oxford House, Gods Lake Narrows, Waasagomach, Island Lake (Garden Hill), St. Theresa Point, Negginan (Poplar River), Pauingassi and Little Grand Rapids.

In Ontario, the following 27 communities are eligible for the Nutrition North Canada Retail Subsidy and for the Harvesters Support Grant: Ogoki, Webequie, Lansdowne House, Eabamet Lake (Fort Hope), Summer Beaver, Wawakapewin, North Spirit Lake, Cat Lake, Poplar Hill, Deer Lake, Favourable Lake (Sandy Lake), Keewaywin, Sachigo Lake, Kasabonika, Angling Lake (Wapekeka First Nation), Wunnummin Lake, Kingfisher Lake, Weagamow Lake, Pikangikum, Kashechewan, Fort Albany, Attawapiskat, Peawanuck, Fort Severn, Bearskin Lake, Muskrat Dam and Big Trout Lake. In addition, the community of Moose Factory is eligible for the Nutrition North Canada Retail Subsidy only during seasonal periods of isolation.

In Quebec, the following 14 communities are eligible for the Nutrition North Canada Retail Subsidy and for the Harvesters Support Grant: Kangiqsualujjuaq, Kuujjuaq, Tasiujaq, Aupaluk, Kangirsuk, Quaqtaq, Kangiqsujuaq, Salluit, Ivujivik, Akulivik, Puvirnituq, Inukjuak, Umiujaq and Kuujjuarapik. In addition, the following eight communities are eligible for the Nutrition North Canada Retail Subsidy only during seasonal periods of isolation: Port-Menier, La Romaine (Gethsémani), Harrington Harbour, Tête-à-la-Baleine, Chevery, Mutton Bay, La Tabatière and Saint-Augustin (Pakuashipi).

In Newfoundland and Labrador, the following seven communities are eligible for the Nutrition North Canada Retail Subsidy and for the Harvesters Support Grant: Black Tickle, Rigolet, Makkovik, Postville, Hopedale, Natuashish and Nain.

In Yukon, the following community is eligible for the Nutrition North Canada Retail Subsidy and for the Harvesters Support Grant: Old Crow.

In the Northwest Territories, the following 13 communities are eligible for the Nutrition North Canada Retail Subsidy and for the Harvesters Support Grant: Wekweètì (Snare Lake), Gameti (Rae Lakes), Lutsel K’e, Sachs Harbour, Ulukhaktok (Holman), Paulatuk, Aklavik, Fort Good Hope (K’asho Got’ine), Norman Wells, Tulita, Colville Lake, Deline and Sambaa K’e. The following three communities are eligible for the Nutrition North Canada Retail Subsidy only during seasonal periods of isolation: Tuktoyaktuk, Wrigley and Fort Simpson. In addition, the following four communities are eligible for the Nutrition North Canada Retail Subsidy during seasonal periods of isolation, the Harvesters Support Grant and the Community Food Programs: Inuvik, Fort McPherson, Tsiigehtchic and Nahanni Butte.

In Nunavut, the following 25 communities are eligible for the Nutrition North Canada Retail Subsidy and for the Harvesters Support Grant: Qikiqtarjuaq, Pangnirtung, Iqaluit, Kimmirut, Clyde River, Cape Dorset, Pond Inlet, Hall Beach (Sanirajak), Naujaat (Repulse Bay), Grise Fiord, Arctic Bay (Ikpiarjuk), Igloolik, Coral Harbour, Resolute, Taloyoak, Kugaaruk, Gjoa Haven, Cambridge Bay, Kugluktuk, Baker Lake, Chesterfield Inlet, Rankin Inlet, Whale Cove, Arviat and Sanikiluaq.

© Library of Parliament