Refugees are people who flee their country because it is unsafe. Most refugees seek protection in a country neighbouring their own. Others make their way to countries like Canada and seek protection once they have arrived. This paper describes the steps to obtain protection when a person is already in Canada.

International law and Canadian legislation provide a framework for identifying whether a person needs protection. Refugee claimants must first approach Canadian officials, who will determine whether they meet certain criteria for referral to the Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada (IRB).

An IRB board member must then decide whether a person has a well‑founded fear of persecution or would face torture or cruel and unusual punishment if returned to the home country. The hearing is usually held in person, and the decision is based on several established grounds. If the person is determined to need protection, a status is conferred that allows the person to apply for permanent residence in Canada.

Individuals who are unable to prove that they need protection face removal proceedings. However, there are several legal options a person may choose to pursue before removal occurs, such as an appeal to the IRB Refugee Appeal Division, judicial review by the Federal Court of Canada, an application for humanitarian and compassionate consideration or a pre‑removal risk assessment.

Individuals who are fleeing life‑threatening circumstances may not have all their identification documents with them on arrival in Canada. When this happens, such individuals are detained until their identity can be established. Other reasons that a person may be detained include the belief that the person will not attend an immigration examination, or when the person is considered a danger to the public.

Canada's Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (IRPA)1 lists a series of objectives with respect to refugees. Foremost among those objectives is "to recognize that the refugee program is in the first instance about saving lives and offering protection to the displaced and persecuted."2 Other key objectives include fulfilling Canada's international legal obligations – including under the 1951 United Nations Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees (the Convention) and its 1967 Protocol,3 assisting refugees in need of resettlement from overseas, and granting fair consideration to those who come to Canada claiming persecution. This paper focuses on the last objective, in other words, the procedure governing claims for refugee protection made in Canada. It does not engage with Canada's international refugee protection and resettlement efforts, which are conducted under a separate legal framework.4

Under the IRPA,

A Convention refugee is a person who, by reason of a well‑founded fear of persecution for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group or political opinion,

- is outside each of their countries of nationality and is unable or, by reason of that fear, unwilling to avail themself of the protection of each of those countries; or

- not having a country of nationality, is outside the country of their former habitual residence and is unable or, by reason of that fear, unwilling to return to that country.5

According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, in 2019 there were 20.4 million persons around the world who fit this definition.6

Because Canada has signed and ratified the United Nations Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment,7 refugee protection under Canadian law is also conferred on "persons in need of protection," that is, those who face a risk, assessed on a case‑by‑case basis, of death, torture, or cruel and unusual treatment or punishment. A person to whom refugee protection is granted in Canada is a "protected person."8

This paper describes the various steps in the refugee determination process in Canada. It also provides information with respect to actions that claimants may take after receiving an initial positive or negative decision regarding an application for refugee status.

The Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada (IRB) is the body responsible for conferring Convention refugee or protected person status in Canada.9 The IRB was established in 1989, after which Canada's inland refugee determination system remained relatively unchanged until 2010 and 2012, when it underwent significant reform.10

The IRB is led by a chairperson appointed by the Governor in Council and an executive director. The Minister of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship reports to Parliament on the activities of the IRB.

The IRB comprises four divisions: the Refugee Protection Division (RPD), the Refugee Appeal Division (RAD), the Immigration Division (ID) and the Immigration Appeal Division (IAD). The ID is responsible for admissibility hearings and detention reviews, whereas the IAD decides appeals of removal orders issued by either the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) or the ID against Convention refugees and other protected persons.

The RPD decides claims made for refugee protection in Canada. Originally appointed by the Governor in Council, RPD Board members are now designated under the Public Service Employment Act. RPD decisions can be appealed to the RAD, subject to certain restrictions (for example, no appeal is allowed if the RPD has found that a claim has no credible basis or is manifestly unfounded).11 Members of the RAD are appointed by the Governor in Council.

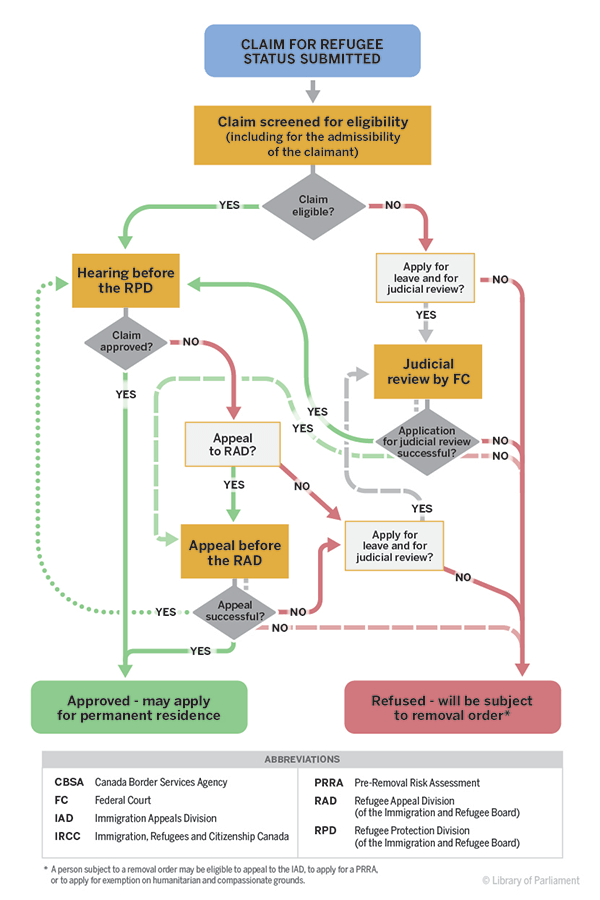

Figure 1 – Overview of Refugee Protection Claims Process in Canada

Figure 1: As outlined in this paper, the refugee determination process in Canada begins with claim eligibility and applicant admissibility screening. Claims for refugee protection that are eligible to be heard proceed to a hearing. Some decisions are subject to judicial review, as discussed in this paper. If a claim for refugee protection is accepted, the applicant may apply for permanent residence. If the claim for refugee protection is rejected, the applicant can: be subject to a removal order and appeal that order to the Immigration Appeal Division; request a pre‑removal risk assessment; or apply for permanent residence on humanitarian and compassionate grounds.

Source: Figure prepared by the Library of Parliament using data obtained from Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (IRPA), S.C. 2001, c. 27.

A person wishing to make a refugee claim must make that claim either at a port of entry to the country (i.e., an airport, a sea port or an official land border crossing) or, within Canada, to an officer of the CBSA or of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC), pursuant to section 99(3) of the IRPA.12 Individuals who cross the border between ports of entry are generally transported to either a CBSA or an IRCC office to make a claim.13

An eligibility interview follows, in which the individual gives personal information and a brief explanation of the individual's reason for seeking protection in Canada. The individual has the burden of proving that the claim is eligible to be referred to the RPD.

The IRPA and associated regulations provide seven main reasons for a refugee claim to be found ineligible:14

People found eligible to have their claims for protection heard by the IRB are issued conditional removal orders, which facilitate the departure of a foreign national if the claim is abandoned or withdrawn, or if it is finally refused and all available recourse is exhausted. Security screening procedures also begin once a claim is deemed to be eligible. Foreign nationals whose claims have been referred to the IRB may apply for a work permit.17

Claimants are registered with the Interim Federal Health Program during their period of ineligibility for provincial or territorial health coverage. The Interim Federal Health Program provides basic, supplemental and prescription drug coverage to refugee claimants, rejected refugee claimants and others in need of Canada's protection.18 In order to receive compensation under this program, health care providers must verify their patients' eligibility each time they provide a service or product.19

Refugee claimants must outline their need for protection in a Basis of Claim (BOC) form. For claims lodged at a port of entry, claimants are to provide a completed BOC form to the RPD within 15 calendar days of their arrival. For claims made at an office of the IRB or CBSA, claimants must provide the BOC form with supporting documents upon presenting the claim. The officers who receive the claim then proceed with the admissibility interview. The RPD may extend these time limits for reasons of fairness and natural justice.20

The IRCC or CBSA officer who refers the claim to the IRB no longer schedules the hearing at the RPD in accordance with the Immigration and Refugee Protection Regulations (IRPR) and the IRB Rules, in light of interim measures that have been in effect since August 2018.21 The hearing must take place within 60 days of referral. Exceptions to these timelines are possible for reasons of fairness and natural justice, or when there is an inquiry regarding national security, war crimes, serious criminality or organized crime, or because of operational limitations at the RPD.22

A 2018 independent review of the Immigration and Refugee Board found that the prescribed timelines for holding hearings were met in only 59% of cases in 2017, down from a high of 65% between 2014 and 2016.23 The IRB reported that these delays were largely attributable to human resources challenges, including insufficient recruitment, and a more complex caseload due to a large number of countries of origin.24

The hearing at the RPD is usually held privately, before one decision‑maker (i.e., an IRB member). The claimant is asked to testify and is provided with an interpreter if not comfortable communicating in English or French. The claimant is also permitted to have the assistance of a representative. On occasion, a hearings officer from the CBSA may also present evidence to exclude the person as a refugee. All supporting documentation must be shared before the hearing. These procedures are set out in the RPD Rules. To support the claim, the claimant usually offers mainly personal testimony, sometimes supported by documentation about the country of origin. However, as the Canadian Council for Refugees has noted, in some cases such documentation can be difficult to gather:

Claimants fleeing a situation that is well‑documented in the human rights reports and frequently seen before the Immigration and Refugee Board may be able to present documentation relatively quickly. On the other hand, women fleeing gender‑based persecution in a country where little attention is paid to women's rights will likely need more time.

…

The same difficulties in collecting documentation apply for claimants fleeing emerging patterns of human rights violations, or [those] from a small and neglected ethnic minority.25

The IRB has a research division that provides basic information about various countries to inform the Board members' decisions.26 Evidence from an expert witness may also be considered in cases involving vulnerable persons (e.g., victims of torture or trauma).27 In cases involving children, evidence from teachers, social workers, medical professionals and others who have dealt with the child may also be considered.28

Most of the time, IRB members render their decisions and reasons for decisions orally after the hearing.

There are important differences between groups of refugee claimants, particularly with respect to access to post‑decision recourse and privileges. The relevant claimant groups are described below, while the corresponding differences are explained in greater detail later in this paper.29

Except for "designated foreign nationals," successful claimants attain the status of Convention refugee or person in need of protection and must apply to become a permanent resident in Canada.

Successful refugee claimants who are "designated foreign nationals" are not eligible to apply for permanent residence status until five years from the date of a final determination of their refugee claim, the date of a final determination following a pre‑removal risk assessment (PRRA), or the date on which they become a designated foreign national.31

Permanent residents enjoy certain privileges, including the freedom to enter and leave Canada and to work without a permit, as well as the possibility of sponsoring their family members to be reunited in Canada. To maintain permanent resident status, individuals must not become inadmissible (for instance, by committing certain crimes) or fail to comply with their residency obligation, which generally requires a physical presence in Canada for at least two years in a five‑year period.32 If they successfully maintain permanent resident status and meet certain other requirements in relation to residence in Canada, knowledge of Canada and language skills, they may eventually apply for Canadian citizenship.33

Under Canadian law, a claim for refugee protection can be rejected and the RPD's decision to accept the claim can be vacated. Decisions in these matters are made by the RPD and may not be appealed to the RAD.

The IRPA allows the Minister of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship to apply for cessation of refugee protection when a refugee's actions indicate that the individual is no longer in need of protection, for example, if a refugee returns to the country of origin on a long‑term basis or acquires the citizenship of another country.34 Upon a final decision that refugee status has ceased, the foreign national who was previously a Convention refugee or person in need of protection loses status and is rendered inadmissible to Canada; this means that the foreign national cannot remain in or enter the country.35 Successful refugee claimants who have become permanent residents are not subject to losing their status through cessation if the reasons for which they sought refugee protection have ceased to exist (IRPA, s. 108(1)(e)), but they can lose their status for the other reasons stated above.

Refugee protection is vacated when the original RPD decision or positive PRRA was obtained through omission or misrepresentation. Misrepresentation renders a foreign national inadmissible to Canada for five years.

If the IRB establishes that a person is neither a Convention refugee nor a person in need of protection, the conditional removal order that was issued comes into effect and the failed claimant must leave Canada within 30 days of the date of the decision.

One component of the government's 2010 and 2012 reforms to Canada's asylum system was the goal of removing failed refugee claimants "as soon as possible." A three‑year evaluation of the reforms found that the CBSA succeeded in removing failed refugee claimants within 12 months following the decision 52% of the time, rather than the targeted rate of 80% of the time.36 While some of the reasons provided for this discrepancy, such as lack of documentation to prove nationality and citizenship, are beyond the control of the CBSA, the evaluation noted that this did not explain the failure to remove people without impediments to removal. The 2018 independent review noted that in 2016, due to relatively low resourcing and prioritization, the removal of failed claimants dropped to 3,892, despite a backlog of 17,000 cases.37

Failed claimants may also seek to remain in Canada or acquire permanent resident status through one of five avenues: application for a temporary resident permit, appeal to the RAD, application for leave for judicial review (and a stay of removal), application for a PRRA or application for permanent residence on humanitarian and compassionate grounds. Each of these processes has limitations and exceptions and is described below.

Temporary resident permits are used to allow a foreign national who would otherwise be inadmissible to enter and stay in Canada temporarily. An individual who is ineligible to be referred to the RPD may apply for a temporary resident permit only if the individual has not applied for a PRRA.38 Most failed refugee claimants may not apply for a temporary resident permit unless they have been in Canada for more than a year following the last decision by the RPD, RAD or Federal Court.39

Designated foreign nationals may not apply for a temporary resident permit until five years after: the date of a final determination of a refugee claim; the date of a final determination of a PRRA; or the date on which they became a designated foreign national.

The provisions implementing the RAD came into force on 15 December 2012. The RAD provides failed claimants with an opportunity to challenge a decision of the RPD, including by introducing evidence about their claim that was not known or available at the time of their RPD hearing; this is a broader recourse than judicial review by the Federal Court (see below). This appeal is normally conducted by paper review, although an oral hearing may be held in certain situations.40 The RAD may refer a matter back to the RPD if it is of the opinion that the RPD decision is wrong in law, in fact, or both. The RAD may also confirm a decision of the RPD or set aside an RPD decision in favour of its own decision.

According to section 159.91 of the IRPR, the notice of appeal before the RAD must be filed within 15 days of receiving the written reasons for the negative RPD decision. Rule 3 of the RAD indicates that the appellant's complete record must be filed within 30 days following the decision. If these time limits cannot be met, the RAD may extend them, in particular for reasons of fairness and natural justice.41 Appeal decisions must be rendered within 90 days in cases where no hearing is held.

An assessment of the reforms conducted three years after they came into force showed that the RAD successfully met the 90‑day timeline in 96% of cases in 2013, but that this figure dropped to 68% in 2014.42 According to the assessment report, factors that contributed to this drop include a heavier workload for decision‑makers following the Federal Court decision in Huruglica v. Canada (Citizenship and Immigration)43 which found that the RAD must review RPD decisions for correctness (to identify possible errors of fact or of law) rather than the lesser standard of reasonableness. As a result, the number of appeals multiplied, but resources did not increase accordingly.

RPD decisions concerning the following five groups of refugee claimants may not be appealed to the RAD: designated foreign nationals, those whose claims have been determined to have been withdrawn or abandoned, those whose claims are found to have no credible basis, those whose claims are found to be manifestly unfounded, and those whose claims are heard as exceptions to the Safe Third Country Agreement.44

Unsuccessful claimants may seek judicial review by the Federal Court if they feel that the decision by the RPD or RAD member might be set aside on the grounds that the tribunal erred in law or failed to observe a principle of natural justice.45

After filing an application for leave and for judicial review with respect to a decision of the RAD, most failed refugee claimants receive an automatic stay, which postpones their removal.46 Certain failed claimants do not receive an automatic stay in such situations, including those with manifestly unfounded claims, those whose claims have no credible basis, those whose claims were made as an exception to the Safe Third Country Agreement, designated foreign nationals and persons who are inadmissible on grounds of serious criminality.47 These individuals may request a stay of removal at the time of filing an application for leave and for judicial review with the Federal Court.

An unsuccessful claimant who is "ready for removal"48 may be eligible for a PRRA, a review currently conducted by officials at IRCC. In this process, submissions are made concerning facts that were not presented to the IRB before, because they were not known at the time. The PRRA is generally a paper review to evaluate the risks that the individual would face if returned to the country of origin, including the risk of persecution, torture, cruel and unusual treatment or punishment, and risk to life. Making a PRRA available ensures that Canada does not violate the principle of non‑refoulement,49 in keeping with its international obligations and the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. A PRRA is offered only when the failed claimant has valid travel documents and the assessment must be completed before removal takes place.

However, there are restrictions on when an application may be submitted for a PRRA. Failed refugee claimants may not apply for a PRRA in the 12 months that follow the date of the last decision of the RPD, RAD or Federal Court. Similarly, those who have received a negative PRRA decision must wait one year before submitting a second PRRA application, which unlike the first, does not stay a removal while the decision is being made.50

The Minister of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship may establish exemptions to the 12‑month waiting period for nationals of a certain country or a class of nationals if events in a country have arisen that could place all or some of its nationals or former habitual residents in a refugee‑like situation.51 Persons whose claims have been vacated or persons who were excluded from the refugee determination process do not have to wait 12 months to apply for a PRRA.

Generally, persons who receive a positive PRRA decision are granted "protected person" status and may apply to remain in Canada as permanent residents, unless they are inadmissible on grounds of security, violation of human or international rights, organized criminality or serious criminality. A positive PRRA decision for such individuals results only in a stay of removal, rather than in protected person status.52

As part of the 2010 and 2012 reforms to Canada's asylum system, the government envisioned consolidating the responsibility for risk assessment by transferring most PRRA decisions to the RPD. The Minister of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship would retain responsibility for decisions regarding persons inadmissible on grounds of security, violation of human or international rights, or serious or organized criminality. This transfer was initially expected to occur in December 2014,53 but was then postponed. An evaluation in 2016 revealed some concerns about the increasing demand for PRRAs and indicated that a decision on the transfer would be taken in 2016–2017 following a complete evaluation of the asylum system reforms and further analysis.54 At the time of writing this background paper, a decision had not yet been made.

Under the IRPR, a person currently has 15 days to respond to a notification regarding eligibility to apply for a PRRA. Neither a decision nor a removal may occur until at least 30 days after the date of notification.55

For those excluded from the refugee determination process because they have made a refugee claim in a country with which Canada has an information‑sharing agreement,56 the PRRA process includes a mandatory oral hearing.57 Guidelines provided by IRCC indicate that the informal hearing or interview is a forum for the discussion of facts identified in the hearing notice.58

The final option for a failed refugee claimant is to apply for permanent residence and discretionary relief from the Minister of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship based on humanitarian and compassionate considerations.59

IRCC officers evaluating such applications are required to consider all the relevant facts holistically in order to determine whether the applicant has demonstrated that removal from Canada would lead to either "unusual and undeserved" or "disproportionate" hardship. Importantly, these terms merely provide guidance to decision‑makers, who are responsible for using them flexibly to fulfil the equitable goals of the IRPA.60 Relevant considerations include the conditions of the country to which the applicant would be sent and the degree to which the applicant is established in Canada. In addition, decision‑makers are required to consider the best interests of any child directly affected by the decision, taking into consideration the child's age, level of development, maturity, capacity and needs.

A humanitarian and compassionate application does not stay the conditional removal that is in effect for the failed claimant unless the application was approved in principle before the removal order came into effect. Although failed claimants may request that the Federal Court suspend removal until the outcome of the application is known, such requests have met with mixed results.

Humanitarian and compassionate applications are not intended to replicate processes or revisit issues that were previously dealt with during the refugee determination process. For that reason, in examining requests made on humanitarian and compassionate grounds in Canada, decision‑makers must not consider the factors used to make assessments within the refugee protection process (i.e., risk of persecution based on grounds set out in section 96 of the IRPA, or risk of torture or cruel and unusual treatment or punishment). Instead, the underlying hardships that may affect the foreign national must be considered.61

In addition, a processing fee must be submitted with an application for permanent residence on humanitarian and compassionate grounds in order for it to be considered.62

Lastly, there are restrictions on when an application for permanent residence on humanitarian and compassionate grounds may be submitted, and by whom. The minister may not examine the request in any of the following circumstances: the foreign national has already made an application on humanitarian and compassionate grounds and the request is pending; the foreign national has a claim pending before the RPD or the RAD; the foreign national has a PRRA pending; or, fewer than 12 months have passed since a decision was made by either the IRB or the Federal Court.63 These restrictions do not apply in cases where there is a risk to life in the country of origin owing to inadequate health or medical care or where removal would have an adverse effect on the best interests of a child directly affected.64

Designated foreign nationals may not apply for permanent residence on humanitarian and compassionate grounds for five years after a final determination on a refugee claim or PRRA or for five years after the day following their designation as foreign national. Foreign nationals who are inadmissible on grounds of security, human or international rights violations, or organized criminality are not eligible to apply for humanitarian and compassionate considerations at all.

In fiscal year 2018–2019, the CBSA detained 8,781 persons.65 The CBSA has three immigration holding centres, located in the Greater Toronto Area, near Montréal, and at the Vancouver Airport. Where there is no immigration holding centre, persons are detained in provincial correctional facilities (usually remand centres or prisons). The reasons for detention and alternatives to detention are described below.

Designated foreign nationals have a specific detention regime: automatic detention upon arrival, first detention review after 14 days and subsequent reviews every six months. The rationale for the detention scheme is twofold: to allow the authorities to proceed with their investigations of all group members, and to act as a deterrent.66

The five potential reasons for detention can apply to refugee claimants at different times in the determination process. The first reason is that a person presents a danger to the public. The second is that there is a flight risk when removal is pending. The third is a belief that the person will not appear for an examination, an admissibility hearing or any immigration process. The fourth reason, which is most often at issue upon the claimant's arrival in Canada, is that the claimant's identity has not been established.67 Lastly, claimants will be detained if there are reasonable grounds to suspect they are inadmissible on grounds of security, violation of human rights or ties to organized crime. A member of the ID of the IRB will review the reasons for detention after 48 hours, again after seven days, and then every 30 subsequent days.68

Indefinite detention is unlawful and each detention review is also an opportunity to present alternatives to detention. A person may be released on terms and conditions, such as regular reporting requirements. There may be a request for a cash bond or for a guarantor to ensure that the person complies with the terms and conditions. Under the National Immigration Detention Framework, the CBSA is expanding alternatives to detention (ATD), which must be considered by ID members in their reviews and serve to mitigate risk factors upon release.69 One of these alternatives is electronic monitoring, which is the basis for a pilot project available in the Greater Toronto Area only. Reporting to the CBSA can now be done with voice biometrics as well as in person. Finally, the ATD program has agreements with community‑based support services, which supervise released individuals and help them obtain services, such as counselling. When an IRB member is considering the release of an individual against whom a danger opinion has been issued on security grounds, 11 prescribed conditions for such release are set out in section 250.1 of the IRPR, such as informing the CBSA of a change in address prior to moving.

The number of persons fleeing for safety worldwide is at an unprecedented high, presenting significant challenges for Canada and the world. Canada continues to focus its approach to processing refugee protection claims on the concepts of fairness and efficiency, among other important objectives.70 However, despite overall continuity in the objectives of refugee protection in Canada, there have been significant changes to the institutions and procedures responsible for fulfilling them. Most notably, the 2010–2012 reforms to Canada's asylum system affected virtually every aspect of Canada's inland refugee determination system, such as the hiring process for RPD members, the implementation of the RAD and restricted access to post‑decision recourse for failed claimants. Evaluations of these changes have revealed that, while the new processes are intended to deal with claims mor quickly, not all the reform objectives have been met. These realities suggest that refugee protection in Canada is likely to evolve further in the years to come.

* This is an updated version of the publication by Julie Béchard and Sandra Elgersma, Refugee Protection in Canada, Publication No. 2011‑90‑E, Parliamentary Information and Research Service, Library of Parliament, Ottawa, 15 July 2013. [ Return to text ]

† Library of Parliament Background Papers provide in‑depth studies of policy issues. They feature historical background, current information and references, and many anticipate the emergence of the issues they examine. They are prepared by the Parliamentary Information and Research Service, which carries out research for and provides information and analysis to parliamentarians and Senate and House of Commons committees and parliamentary associations in an objective, impartial manner. [ Return to text ]

A medical, psychiatric, psychological or other expert report regarding the vulnerable person is an important piece of evidence that must be considered. Expert evidence can be of great assistance to the IRB in applying this guideline if it addresses the person's particular difficulty in coping with the hearing process, including the person's ability to give coherent testimony.

[ Return to text ]

© Library of Parliament