Aquaculture production has seen important growth over the past 40 years, both in Canada and worldwide. British Columbia leads Canada’s finfish production (principally salmon), while Prince Edward Island leads the country’s shellfish production (principally mussels). In 2023, 145,985 tonnes of seafood were produced by Canada’s aquaculture sector, valued at more than $1.2 billion, contributing to the local economies of many small and coastal communities.

The regulatory framework of Canada’s aquaculture industry is shared between the federal and provincial governments. Further complicating matters is the fact that certain regulatory responsibilities can vary by province. In addition to recent regulatory reforms, a federal Aquaculture Act has been proposed to help clarify the division of powers and to simplify the regulatory regime both for industry and the public. While draft provisions have been shared publicly by the Government of Canada, no new federal Act has been tabled in Parliament.

In addition to regulatory uncertainty, Canada’s aquaculture industry continues to face challenges, including concern over environmental impacts, negative public perceptions and global competition. However, many opportunities, such as emerging technologies, increased Indigenous participation and industry transparency, are key issues for stakeholders.

Aquaculture has been part of Canada’s economy for decades, and environmentally sound aquaculture could contribute to the further development of Canada’s sustainable ocean economy, also called the “blue” economy.

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) explains that

aquaculture covers the farming of both animals (including crustaceans, finfish and molluscs) and plants (including seaweeds and freshwater macrophytes) … in both inland (freshwater) and coastal (brackishwater, seawater) areas.1

This HillStudy examines aquaculture production in Canada, the employment opportunities it fosters and the unique regulatory framework surrounding the industry, including recent regulatory reforms. Some of the challenges and opportunities the aquaculture industry faces in Canada are also examined.

In Canada, 45 species are commercially cultivated (i.e., grown in aquaculture facilities), including finfish, shellfish and marine plants.2 Coastal open-net pen production of finfish is the most common type of aquaculture practised in the country. Many other forms of aquaculture production also exist, including freshwater net-pen, land-based systems and intertidal bottom culture enhancement, among others, as shown in Figure 1 below.3

In 2023, Canada produced 145,985 tonnes of aquaculture products, valued at more than $1.2 billion.4 For finfish, salmon led in terms of both quantity produced and value. In the shellfish category, mussels dominated in terms of quantity produced, whereas oyster production had the greatest value.

The aquaculture industry has grown considerably over the years. Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s (DFO’s) aquaculture production statistics are available from 1986. That year, 10,488 tonnes of aquaculture products were produced in Canada, which were valued at $35.1 million5 (worth approximately $82.9 million In 2023 dollars6). Cultured finfish species at the time consisted of salmon, trout and steelhead, while cultured shellfish mostly consisted of oysters and mussels.

Comparatively, In 2023, Canada’s freshwater and sea commercial fisheries (i.e., wild capture fisheries) landed (i.e., put ashore) 679,062 tonnes of seafood, valued at nearly $3.7 billion.7

In 2023, British Columbia (B.C.) led Canada’s finfish aquaculture sector, primarily through the production of salmon. The province accounted for 51,374 tonnes – roughly 48% of the country’s total finfish output – valued at almost $523 million (see Table 1).8 That same year, Prince Edward Island (P.E.I.) was the leading producer of shellfish in Canada, with 20,304 tonnes produced – principally mussels – representing almost 52% of all shellfish produced in Canada. The province’s shellfish production was worth almost $47 million In 2023 (see Table 2).

| Province | Production (tonnes) | Value ($ thousands) |

|---|---|---|

| British Columbia | 51,374 | 523,005 |

| Alberta | 498 | 4,774 |

| Saskatchewan | 1,752 | 8,759 |

| Manitoba | 74 | 384 |

| Ontario | 3,194 | 34,426 |

| Quebec | 1,036 | 8,746 |

| New Brunswick | 22,780 | 258,087 |

| Nova Scotia | 10,411 | 107,723 |

| Prince Edward Island | 380 | 4,300 |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 15,645 | 177,250 |

| Canada | 107,144 | 1,217,454 |

Source: Table prepared by the Library of Parliament using data obtained from Government of Canada, Aquaculture production quantities and value, 2023.

| Province | Production (tonnes) | Value ($ thousands) |

|---|---|---|

| British Columbia | 9,588 | 34,887 |

| Quebec | 339 | 3,380 |

| New Brunswick | 2,640 | 26,184 |

| Nova Scotia | 1,532 | 7,030 |

| Prince Edward Island | 20,304 | 46,969 |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 4,297 | 8,050 |

| Canada | 38,699 | 126,500 |

Note: Production and value statistics for Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba and Ontario are not reported by Fisheries and Oceans Canada; thus, they are not included in Canada’s totals.

Source: Table prepared by the Library of Parliament based on data obtained from Government of Canada, Aquaculture production quantities and value, 2023.

According to the Government of Canada, In 2023, more than 3,675 Canadians were directly employed in the aquaculture industry.9 As of 2024, there were 615 aquaculture-based businesses in the country, of which nearly all (96.7%) were categorized as a business with 99 employees or fewer.10

In Canada, jurisdiction over the management of the aquaculture industry is shared between the federal and provincial governments, with specific regulatory responsibilities varying by province. Two provinces, B.C. and P.E.I., have special arrangements with the federal government that govern aquaculture management in their jurisdictions.

A 2009 Supreme Court of British Columbia decision (Morton v. British Columbia [Agriculture and Lands])11 categorized aquaculture in that province as “a fishery,” and since fisheries fall within federal jurisdiction, the federal government was confirmed as the primary aquaculture regulator in that province. In 2010, the federal and B.C. governments signed a memorandum of understanding entitled the Canada–British Columbia Agreement on Aquaculture Management, which clarifies the roles and responsibilities of each level of government as they pertain to aquaculture in the province.12

In P.E.I., the provincial government came to an agreement with DFO and the aquaculture industry in 1928 to establish the PEI Aquaculture Leasing and Management Board (now known as the PEI Shellfish Aquaculture Management Advisory Committee).13 Under this agreement, the advisory committee regulates access, manages property records and ensures compliance with lease contracts, among other tasks. The committee, consisting of federal, provincial and industry representatives, provides advice and direction to DFO regarding various federally managed aspects of the industry. DFO retains jurisdiction over aquaculture leases, which are issued by its PEI Aquaculture Leasing Division.14

To date, there have been no similar court decisions or agreements affecting other provinces. Consequently, in these jurisdictions, the overall management of the aquaculture industry remains shared between the federal and provincial governments. Certain aspects of aquaculture management are assigned exclusively to one level of government, while others are shared. Table 3 outlines the main responsibilities related to aquaculture management in Canada and the level of government responsible for each.

| Management Area | British Columbia | Prince Edward Island | Rest of Canada |

|---|---|---|---|

| Site approval | Shared responsibility | Shared responsibility | Provincial responsibility |

| Land (seabed) management | Provincial responsibility | Federal responsibility | Provincial responsibility |

| Day-to-day operations and monitoring of facilities | Federal responsibility | Federal responsibility | Provincial responsibility |

| Introductions and transfers of live eggs and fish | Shared responsibility | Shared responsibility | Shared responsibility |

| Drug and pesticide approvals | Shared responsibility | Shared responsibility | Shared responsibility |

| Safety and quality of fish harvested and sold | Federal responsibility | Federal responsibility | Federal responsibility |

Sources: Table prepared by the Library of Parliament using information obtained from Government of Canada, Infographic: How fish farming is regulated in Canada; and Government of Canada, Role of provinces and territories.

Under the Fisheries Act,15 the Minister of Fisheries and Oceans “regulates the aquaculture industry in order to protect fish and fish habitat. The Act sets out authorities on fisheries licensing, management, protection and pollution prevention.” 16

Several Fisheries Act regulations pertain to the management of aquaculture activities within Canada. Most prominent among them are the Pacific Aquaculture Regulations and Aquaculture Activities Regulations.17

Adopted In 2010, the Pacific Aquaculture Regulations provide the framework within which aquaculture activities (i.e., marine, freshwater and land-based operations) take place in B.C. and outline aquaculture licensing requirements.18

Adopted In 2015, the Aquaculture Activities Regulations “clarify conditions under which aquaculture operators may treat their fish for disease and parasites, deposit organic matter and manage their facilities under sections 35 and 36 of the Fisheries Act” 19 in all provinces, except B.C. The regulations also impose reporting requirements for environmental monitoring and sampling.

Aquaculture producers are required to report certain types of information pertaining to their facilities on a yearly basis, and DFO shares this information with the public through the Open Government portal.20 Data is available for land-based, freshwater and marine facilities. The information shared is facility-specific and includes the instances where:

DFO offers additional information specific to B.C. aquaculture facilities on escapes (i.e., finfish escaping their enclosures), benthic monitoring (i.e., monitoring of the ocean floor beneath finfish pens) and other topics.22

Reporting requirements and frequency can be found within regulations or within the conditions listed in aquaculture licences.23 Public reporting of aquaculture data is intended to “enhance [the industry’s] transparency and accountability.” 24

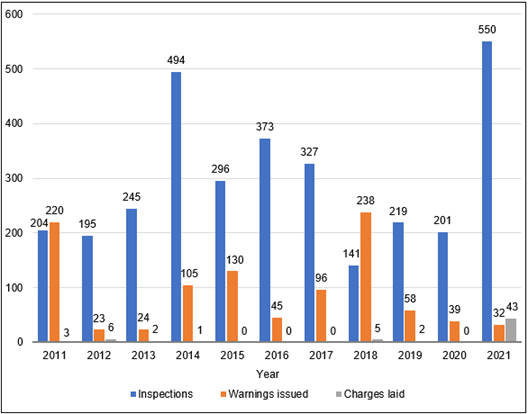

Pursuant to Fisheries Act regulations, aquaculture facilities must be monitored and inspected. Between 2011 and 2021, 3,245 inspections were conducted by DFO fishery officers, 1,010 warnings were issued, and 62 charges were laid (see Figure 2).25

Figure 2 – Aquaculture Facility Inspections Conducted Pursuant to Fisheries Act Regulations, Warnings Issued and Charges Laid, 2011–2021

Source: Figure prepared by the Library of Parliament based on data obtained from Government of Canada, “Key results,” Management of Canadian aquaculture.

Charges included violations of reporting requirements, illegal transportation, exceeding the maximum allowable biomass, activities occurring outside the designated time or area and attempting to obstruct or hinder a fishery officer. Charges are not always laid as a result of non-compliance; this decision depends on the severity of the violation. In addition to laying charges, fishery officers can recommend education, require changes or issue warnings. “A risk-management approach is used to determine the frequency of inspections and operations to be inspected.” 26

Prior to 2018, the focus of federal aquaculture enforcement efforts was on marine finfish aquaculture, but In 2018, the Pacific shellfish sector became a greater target of enforcement activities, “which has resulted in a lower reported rate of overall compliance due to an increase in warnings issued and charges laid.” 27 In addition, “the conditions of licence for shellfish aquaculture were updated In 2021 to address the issue of marine plastic debris and ghost gear in British Columbia’s coastal waters.” 28

The idea of a federal Aquaculture Act has been discussed for years. The industry’s shared jurisdiction between the federal and provincial governments adds a layer of complexity to any future legislative drafting. To further complicate matters, the divided powers are shared differently between the two levels of government in some provinces, making the regulatory framework difficult to navigate.

Following a Canadian Council of Fisheries and Aquaculture Ministers meeting in December 2018, ministers “agreed to the development of a federal Aquaculture Act that will enhance sector transparency, facilitate the adoption of best practices and provide greater consistency and certainty for industry.” 29

As outlined in section 5 of this HillStudy, the Canadian aquaculture industry is federally regulated pursuant to the Fisheries Act. However, the Fisheries Act was not originally designed to regulate that industry; it was designed to regulate and manage wild capture fisheries.30 A new federal Aquaculture Act could accomplish the following:

DFO has undertaken certain steps to prepare for the introduction of new aquaculture legislation. In 2019, the department held more than 20 engagement sessions across Canada and provided online engagement activities.32 The Minister of Fisheries, Oceans and the Canadian Coast Guard’s 2019 mandate letter from the prime minister included the task of beginning work “to introduce Canada’s first-ever Aquaculture Act.” 33 In 2020, DFO published a discussion paper entitled A Canadian Aquaculture Act, which outlined the key elements and authorities that would be included in the proposed federal Aquaculture Act.34

In 2020, the federal government published on its website the main sections that it proposed should be added to a draft Aquaculture Act,35 including provisions that would be replicated from the Fisheries Act and new provisions. The Minister of Fisheries, Oceans and the Canadian Coast Guard’s 2021 mandate letter reiterated the objective of introducing an Aquaculture Act; however, at the time of writing, no government bills have been tabled in Parliament related to the creation of such an Act.

The potential negative effects of aquaculture production on the environment are a constant challenge for the industry and have been for decades. Unlike traditional farming, aquaculture (apart from land-based facilities) takes place in public waters, and its mismanagement can have significant harmful environmental impacts. The following concerns are often cited:

As the department charged with regulating aquaculture at the federal level, DFO is also responsible for communicating information about the industry. In view of concerns about environmental impacts, stakeholders have noted that there is a need for better communication of the scientific findings that underpin government decisions. In a December 2018 report, the Independent Expert Panel on Aquaculture Science reported that it was “challenging at times to retrieve information on existing science reports, research programs or research findings” related to aquaculture on the DFO website. The panel recommended that DFO create an aquaculture information portal and tailor the information for target audiences, such as the public, scientists and industry. This portal would allow “information on scientific findings, scientific uncertainties and science‑informed decisions to be communicated at the appropriate level.” 37

DFO has since published on the federal government’s website an aquaculture information page that brings together information on statistics, regulations, environmental management, reporting, science and more.38 Information is not, however, tailored to target audiences, as was suggested by the Independent Expert Panel on Aquaculture Science.39

The Cohen Commission of Inquiry into the Decline of Sockeye Salmon in the Fraser River was established by the Government of Canada In 2009.40 The commission’s final report, released In 2012, included 75 recommendations, 13 of which were related to aquaculture. One of the 13 recommendations was to prohibit aquaculture facilities in the Discovery Islands pending further research of their impact on wild sockeye salmon stocks.

In 2010, DFO produced a report that studied the feasibility of moving B.C. aquaculture to closed-containment facilities (i.e., aquaculture facilities that limit interactions with the aquatic environment, which can be land-based or floating).41 Closed-containment salmon aquaculture was also studied In 2013 by the House of Commons Standing Committee on Fisheries and Oceans, and aquaculture more generally was studied by the Standing Senate Committee on Fisheries and Oceans In 2016.42

More recently, DFO conducted risk assessments on nine pathogens known to cause disease from aquaculture operations in the Discovery Islands area. Drawing on scientific reports it published between 2017 and 2020, DFO estimated that the risk to wild Fraser River Sockeye salmon populations from all nine pathogens was “minimal.” 43 However, this conclusion has been criticized by stakeholders as it did not seem to take into consideration the transfer of sea lice from cultured to wild salmon stocks or the currently fragile nature of wild salmon stocks in B.C.44

In December 2020, following consultations with local First Nations, the Minister of Fisheries, Oceans and the Canadian Coast Guard announced that salmon aquaculture facilities in the Discovery Islands area would be phased out within 18 months; no new fish may be introduced into existing facilities within the area; and all aquaculture facilities in the area would be free of fish by 30 June 2022, with the exception of existing fish that had yet to complete their growth cycle.45 The decision affected 19 aquaculture facilities in the area, nine of which were already fallow (i.e., no fish were being cultivated) at the time of the announcement.

In the 2019 mandate letter from the prime minister, the Minister of Fisheries, Oceans and the Canadian Coast Guard was specifically instructed to “[w]ork with the province of British Columbia and Indigenous communities to create a responsible plan to transition from open net-pen salmon farming in coastal British Columbia waters by 2025.” 46 In November 2020, DFO announced that the Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister of Fisheries, Oceans and the Canadian Coast Guard would be responsible for “engaging with First Nations in B.C., the aquaculture industry, and environmental stakeholders” to transition away from open-net pen aquaculture in B.C. There was no explanation at that time, however, of what the alternative for open-net pen salmon farming would be.47

The Government of Canada consulted Canadians on an open-net pen transition plan for B.C. aquaculture In 2022, and in June 2024 it issued a policy statement announcing that open-net pen salmon aquaculture would be banned in coastal B.C. waters. Under the new policy, all current activities will be phased out by the end of June 2029. In September 2024, the Draft Salmon Aquaculture Transition Plan for British Columbia was released.48 In the draft transition plan, the federal government proposed containment-based salmon aquaculture facilities as an alternative to open-net pen salmon farming. The plan proposes four “themes” to be used to develop a new closed containment salmon aquaculture industry in B.C.:

Although the draft transition plan focusses on collaboration between the federal and B.C. governments and First Nations, collaboration with industry is not a prevalent theme. The plan has been criticized by the salmon aquaculture industry and other stakeholders because it does not outline concrete steps that will lead to the implementation of a closed containment industry. Some industry stakeholders stressed that a 2029 target date is unrealistic and will lead to the loss of over $1 billion in economic activity.50 Legal action against the federal government’s decision has also been undertaken by various aquaculture producers in the province.

The B.C. Minister of Water, Land and Resource Stewardship issued a statement in June 2024 about the draft transition plan and stressed the importance of the federal government ensuring that funding is made available to guarantee that workers and communities are not negatively impacted by the transition away from open-net pen aquaculture.51

Aquaculture is a global industry, with the FAO reporting a rise in aquaculture production worldwide of 527% between 1990 and 2018.52 The organization also noted that such an increase in production can be maintained only by ensuring a sustainable approach is applied to aquaculture development. Employment attributed to aquaculture In 2022 was estimated to be 22 million jobs worldwide.53

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) reported that In 2022, Canada ranked 22nd in aquaculture production worldwide, by weight.54 Canada must therefore compete with much larger producer countries to secure and retain export markets. That same year, the OECD reported that the top three aquaculture producers were China, Indonesia and India.

Between 2007 and 2019, DFO published, in partnership with the Aquaculture Association of Canada, a biennial review of Canadian aquaculture research and development projects conducted by researchers across Canada during the previous two years. These projects covered a variety of topics, including fish health, production, husbandry technology, nutrition and environmental interactions.55

In 2021, the BC Salmon Farmers Association published its Innovation and Technology Report describing some of the new industry-led management measures and technologies that are being implemented on a trial basis, including ocean-based semi-closed containment systems, sea lice prevention and treatment methods, and the integration of clean energy sources.56

Canada commercially cultivates 45 species of finfish, shellfish, and marine plants. Thus, a variety of Canadian fisheries products can be and are marketed nationally and internationally.57 Specialty, high-value products are also being produced by the aquaculture industry. For example, certain land-based facilities in Canada produce products such as caviar.

Many Canadian aquaculture companies have been accredited by third parties for various certifications, including for best aquaculture practices and for sustainable seafood production, while some facilities have been certified organic. These certifications can increase marketability and revenues for industry and provide added assurance of responsible seafood farming practices for consumers.58

From 2013 to 2018, the Aboriginal Aquaculture in Canada Initiative worked to increase the participation of Indigenous communities in Canada’s aquaculture industry.59 It hosted workshops and helped communities by providing technical expertise and helping to develop feasibility studies and pilot projects, among other supports.

Following the sunsetting of the initiative, funding and support were made available through the Northern Integrated Commercial Fisheries Initiative, which “supports [the] development of Indigenous-owned communal commercial fishing enterprises and aquaculture operations.” 60 Increasing Indigenous participation in the aquaculture industry could help expand the sector, create employment opportunities for Indigenous communities and advance reconciliation while contributing to the growth of Canada’s blue economy.61

Stakeholders have suggested that the introduction of a federal Aquaculture Act could help reduce the regulatory uncertainty affecting the aquaculture industry. It could also help Canadians better understand how the industry is regulated and clarify the responsibilities of the various levels of government.

Providing scientific information in user-friendly formats and tailoring the information to different audiences (e.g., the public, scientists or aquaculture producers) could also increase transparency and improve public understanding of the industry and its practices.

The aquaculture industry plays an increasingly important role in Canada’s fisheries economy; its impact is most significantly felt in the coastal communities in which most production facilities are located. However, regulatory uncertainty and the cost of mitigating environmental impacts may be affecting the expansion of the industry.

Stakeholders have suggested that new reporting and monitoring requirements and increased transparency, along with the enactment of a federal Aquaculture Act, may help address public and industry concerns alike. The implementation of emerging technologies and innovative solutions to common problems (e.g., sea lice management) by producers may also increase public support, boost production and reduce the environmental impacts of aquaculture facilities. Despite the challenges it faces, a sustainable aquaculture industry could play a key role in the growth of Canada’s blue economy.

© Library of Parliament