In Canada, the systems of early childhood education and care services are different from one province or territory to another; they differ significantly in their affordability, accessibility and rate of participation. These factors affect the labour force participation of parents of young children, particularly mothers. Currently, the federal government supports early childhood education and care services through various means, including transfer payments to the provinces and territories, and tax measures. However, many stakeholders believe that the federal government should do more in this area and help develop a national system for early childhood education and care. The federal government has already indicated that it wants to develop a Canada-wide system inspired by Quebec’s educational child care services. Studies of the Quebec model have revealed successes, particularly in terms of the centres de la petite enfance [Quebec’s early childhood care centres], and the increased rate of employment among women. These studies also revealed limitations, for example, the shortage of subsidized spaces and the poor quality of services in some child care settings where disadvantaged children are over-represented. Lastly, some factors are frequently raised with regard to a potentially greater federal commitment in this area, including the need for early childhood education and care services that take into account the diverse realities of families and that meet certain quality criteria.

For decades, the federal government has been looking to develop early childhood education and care services in Canada, while taking into account the division of powers with the provinces and territories. These services are intrinsically linked to the participation of parents, particularly mothers, in the labour force. Moreover, quality early childhood education and care can help create equal opportunities for children from different socio-economic backgrounds by preparing them for school. As Canada will need to orchestrate its economic recovery in the wake of the COVID‑19 pandemic, the need for early childhood education and care services will be a key issue so that all Canadians, including the parents of young children, are able to participate in the labour force.

This study begins by presenting recent data on parents’ participation in the labour force and the use of early learning and child care services in Canada. It then examines the federal government’s role in early childhood education and care, including its key actions in this area. Then, given that Quebec’s system of educational child care services is the most developed in Canada and that the federal government has indicated that it could draw on it to create a national system, information is provided on how it works, how it is funded and what impact it has on children’s development and on the employment rate of women in Quebec. Lastly, this document outlines some factors to consider in the potential development of a national system of early childhood education and care in Canada.

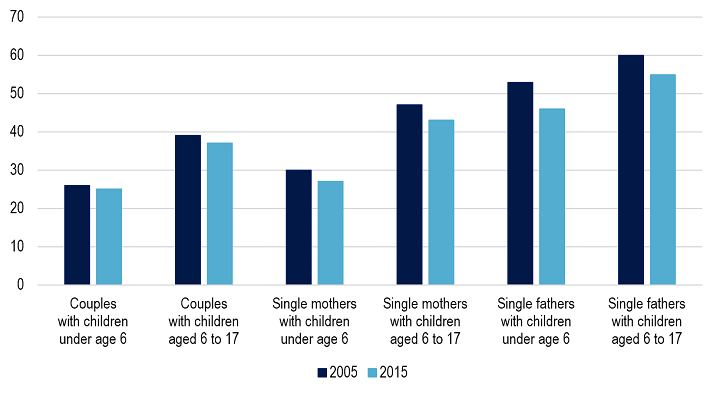

In 2015, only one-quarter (25%) of couples with children under the age of 6 had two parents working full time year-round, a significantly smaller proportion than couples with older children (37%) or no children (41%). The most common situation for a couple with one or more children under the age of 6 was where one parent worked full time year-round, and the other worked part time (fewer than 30 hours per week) or only part of the year.1

Among single-parent families, 81% of which were composed of single mothers, a minority of parents with children under the age of 6 worked full time year-round (27% of mothers and 46% of fathers). One-third of single mothers of children under the age of 6 reported not working in 2015. In addition, labour force participation among single parents fell by several percentage points between 2005 and 2015 for both mothers and fathers.2

Figure 1 shows changes in full-time, year-round work among parents of children under the age of 18, between 2005 and 2015. Note that families are grouped by the age of their youngest child and that the couples shown are those in which both parents worked full time year‑round.

Figure 1 – Full-Time, Year-Round Work, Various Types of Families with One or More Children, 2005 and 2015 (%)

Source: André Bernard, Results from the 2016 Census: Work activity of families with children in Canada, Insights on Canadian Society, Statistics Canada, 15 May 2018.

However, labour force participation among parents of children under age 6 varies across the provinces and territories. In 2015, the largest proportion of couples in which both parents worked full time was in New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, Quebec, the Northwest Territories and Yukon, while the smallest proportion of such couples was in Nunavut, Alberta and British Columbia. According to Statistics Canada, several factors could explain these variations, including differences in child care costs and median incomes.3

In Canada, the labour force participation rate of mothers is lower than that of women without children and that of men (with or without children). In 2016, 71% of women aged 15 to 44 with one or more children under age 3 were in the labour force, compared to 77% of women of the same age without children or with older children. In Quebec, 80% of mothers with children under age 3 were in the labour force, a difference that researchers attribute to Quebec’s family policies for affordable child care services.4 Further, it should be noted that the adverse impact of the COVID‑19 pandemic on the Canadian economy in 2020–2021 has had a particular effect on women’s participation in the labour force, especially for mothers with young children.5

In 2018–2019, approximately two-thirds of children aged 1 to 5 in Canada were in child care. An additional 6% of children aged 0 to 5 were not in child care, but attended kindergarten. Among infants under 1 year of age, 24% were in child care. This lower percentage may be linked to parental leave taken during the child’s first year of life. In total, nearly 1.4 million children aged 0 to 5 years were in child care at the beginning of 2019.6

Child care participation rates vary across the provinces and territories. For example, in 2019, 78% of Quebec children aged 0 to 5 were in child care. This is the highest rate in Canada. In contrast, in Nunavut, only 37% of children aged 0 to 5 were in child care. Attendance rates were lower in Ontario (54%), Manitoba (51%), Saskatchewan (53%) and Alberta (54%) than in the Atlantic provinces (61% to 66%), except in Newfoundland and Labrador (58%). Participation rates in British Columbia, Yukon and the Northwest Territories ranged from 56% to 59%.7

Types of child care arrangements also vary by the child’s age and by province or territory. Almost half of children under the age of 1 are cared for by a relative, while the majority of children aged 1 and older are in a daycare centre, preschool or centre de la petite enfance (CPE) [early childhood care centre in Quebec]. In some provinces, like Newfoundland and Labrador (43%), a large proportion of children are cared for by a relative, while elsewhere, daycare centres are predominant. In Quebec, children are less likely to be cared for by a relative, but more likely to be in a home daycare.8

In 2019, of the parents whose children aged 0 to 5 were in child care, 36% reported difficulty finding a child care or early learning service for their children. This rate also varied between provinces, ranging from 30% in Quebec to 52% in Manitoba. Parents cited cost, accommodation of work schedules and the quality of care among the difficulties they encountered finding child care services.9 Since only parents whose children were in child care were included in these statistics, these percentages would presumably have been higher if parents whose children were not in child care due to lack of space, high costs or other factors had been included.

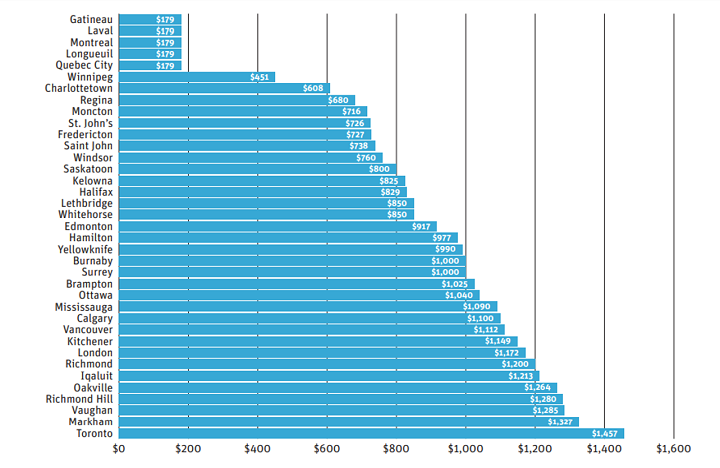

Figure 2 – Monthly Median Child Care Fees for Children Aged 2 to 3 in Various Canadian Cities, 2019

Source: David Macdonald and Martha Friendly, In progress: Child care fees in Canada 2019 ![]() (623 KB, 43 pages), Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, March 2020, p. 14.

(623 KB, 43 pages), Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, March 2020, p. 14.

Difficulty finding child care has consequences for parents, particularly for their ability to work. Of the parents who had difficulty finding child care, 40% had to change their work schedule, 33% had to reduce their work hours and more than 25% had to postpone their return to work.10

Lastly, note that there are several reasons for which some families do not use child care. In particular, 17% of families with children aged 0 to 5 had a parent who decided to stay at home, 10% had a parent on maternity or parental leave, and 6% had a parent who was unemployed. In addition, 10% of children aged 0 to 5 did not attend child care because the costs were too high, while 3% were unable to secure a space. These diverse factors also vary across the provinces and territories.11

In Canada, early childhood education and care services are primarily a provincial and territorial responsibility.12 As a result, there are as many systems of care as there are provinces and territories, and these systems differ significantly. The federal government’s involvement in child care is primarily through transfer payments to the provinces and territories, particularly through the Canada Social Transfer and bilateral agreements for early learning and child care. It also plays a more direct role in funding early learning and child care programs for certain groups of people, including Indigenous populations.

Adopted in 2017, the Multilateral Early Learning and Child Care Framework is the foundation for bilateral agreements with the provinces and territories for early learning and child care. These agreements represent a total federal investment of $1.2 billion over three years.13 In July 2020, an additional $625 million in funding for the provinces and territories was announced for 2020–2021 under the Safe Restart Agreement to support child care in response to the COVID‑19 pandemic.14 In addition, the Indigenous Early Learning and Child Care Framework provides $1.7 billion over 10 years starting in 2018–2019.15

The federal government also incurs tax expenditures, such as the child care expense deduction, which is applied to personal income tax, and the Goods and Services Tax (GST) exemption for child care services.

Table 1 shows expenditures incurred for these two measures, which unexpectedly fell in 2020–2021, possibly due to the COVID‑19 pandemic and its impact on the use of child care services. These expenditures grew steadily through 2019, and according to projections made in February 2020, they were to continue growing in 2020–2021. However, those projections were revised downward in February 2021.

| Federal Expenditures | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child care expense deduction | February 2020 Estimates/Projections | 1,320 | 1,365 | 1,415 | 1,455 | 1,500 | n/a |

| February 2021 Estimates/Projections | 1,320 | 1,355 | 1,380 | 970 | 1,135 | 1,360 | |

| Exemption from GST for child care | February 2020 Estimates/Projections | 180 | 185 | 195 | 200 | 210 | n/a |

| February 2021 Estimates/Projections | 185 | 190 | 200 | 140 | 175 | 210 | |

Source: Table prepared by the Library of Parliament using data obtained from Government of Canada, Report on Federal Tax Expenditures – Concepts, Estimates and Evaluations 2020: part 2; and Government of Canada, Report on Federal Tax Expenditures – Concepts, Estimates and Evaluations 2021: part 2.

In addition, other federal programs are indirectly linked to child care. For example, the Canada Child Benefit provides a tax-free monthly payment to families with a child or children under the age of 18. The amount paid is based on the number of dependent children, age of the children and net family income (in 2021, the maximum monthly amount is approximately $564 per child).16 In addition, the Employment Insurance program includes maternity and parental benefits for new parents.17

In terms of previous federal programs, the Universal Child Care Benefit was in effect from 2006 to 2016. It provided a fixed, taxable monthly payment to all families with children under the age of 18; in 2015, this amount was $160 per child under the age of 6 and $60 per child aged 6 to 17. This benefit was replaced by the Canada Child Benefit in 2016.18

Quebec has the most comprehensive system of educational child care services in Canada. Quebec’s early learning and child care program was launched in 1997. When it began, it extended access to full-day kindergarten to all 5-year-olds and provided subsidized child care spaces for 4-year-olds. The child care program was gradually extended to younger children and made available to all children aged 0 to 4 in September 2000. In the interim, low-cost child care became available before and after school for all children aged 5 to 12 in September 1998.19

Initially, the parents’ contribution for subsidized child care for children aged 0 to 4 was set at $5 per day, and it increased to $7 per day in 2004.20 Since then, the parents’ contribution has gradually risen, and stood at $8.50 at the time of writing.21

As of 31 March 2020, a total of 235,731 subsidized spaces were available in Quebec. Of these, 41% were in CPEs,22 39% in certain home daycares and 20% in certain subsidized child care centres.23 However, the number of children who need child care in Quebec is greater than the number of subsidized spaces available. In November 2019, a total of 55,000 children were awaiting a space.24 Consequently, parents who use non subsidized child care are entitled to a refund of 26% to 75% of child care costs, depending on their income, in the form of a tax credit. In most cases, the refund can be made as an advance payment each month. This refundable tax credit applies to many types of child care expenses, including those paid for a non-subsidized child care space (70,421 licensed spaces in 2020, or 23% of all licensed child care spaces), summer camp, and wages of an in-home child care provider (other than the child’s parent or the parent’s spouse).25

In 2018–2019, the Quebec government spent just over $2.37 billion on its child care program – a stable figure, averaging $2.4 billion per year since 2014.26 The projected spending for this program in 2019–2020 was $2.63 billion.27

These amounts do not include the cost of the refundable child care tax credit, which was projected to be $732 million for 2020.28 The costs associated with kindergarten, pre-kindergarten and school-based child care are also not included in these amounts; they come under the responsibility of the Ministry of Education and are accounted for under the general heading of “Preschool, Primary and Secondary Education.” It should be noted that the Canada–Quebec Early Learning and Child Care Agreement provides $87.4 million in federal funding for each of the three years of the agreement.29 However, “[a]s Quebec has been funding its own early learning and child care system of centres de la petite enfance since 1997, Quebec will use the contributions paid under this Agreement to fund additional direct services for families.”30

A consensus has not been reached concerning the impact of Quebec’s child care system on child development. While many Canadian and international studies point to the benefits of early childhood education for children’s cognitive and behavioural development, particularly for the most vulnerable children,31 some researchers who have examined the Quebec model have identified limitations in the system.

Two controversial studies, conducted by the same group of researchers in 2005 and 2015, found that Quebec’s child care system produced long-term negative effects on children’s non-cognitive abilities, such as behaviour and mental health, especially among boys.32

Another study, conducted in 2013, found that Quebec’s child care system had negative effects on the cognitive development of the 4- to 5-year-old children of less educated mothers. The study’s authors explained that this may not be due to the use of child care per se, but rather to the long hours some children spend in child care, especially before age 2, and the poor quality of service in some child care settings where children from low-income families are over-represented, according to the findings of studies and audits conducted in 2005 and 2011.33

In general, the studies and audits show that the quality of services offered in CPEs is higher than in other types of child care services, including in terms of compliance with regulations on child care staff qualifications.34 However, CPEs account for only one-third of all recognized child care spaces in Quebec.35 In 2020, the Auditor General of Quebec noted that children in disadvantaged circumstances were under-represented in CPEs and recommended that the Quebec Ministry of Families “ensure that children living in precarious socio-economic conditions or those with special needs have access to affordable child care services that meet their needs.”36

Many researchers consider the increase in the participation of Quebec women in the labour force to be the main achievement of the province’s system of educational child care services.37 In Quebec, the participation rate of mothers of children aged 3 to 5 rose from 67% (the second lowest figure in the country) in 1998 to 82% (the second highest in the country) in 2014, an increase of 15 percentage points. During this period, the average participation rate among mothers of 3- to 5-year-olds in Canada rose by 6 percentage points, from 71% to 77%.38 One study conducted in 2008 found that “almost 70,000 more mothers were employed as a result of universal access to low-cost child care in Quebec than without such a program,” representing a 3.8% increase in the employment rate among women.39

In another 2008 study, different researchers found that Quebec’s affordable child care policy had long-term effects on the employment rate of mothers who benefited from the program when their child was under the age of 6, particularly mothers who have not attended university and whose labour force attachment is traditionally weaker. The employment rate among these mothers stayed higher once their children started elementary school.40

In 2017, researchers at the Fraser Institute questioned the extent to which the increased labour force participation among women in Quebec can be attributed to the province’s child care policies. They argued that federal employment insurance reforms have had a significant impact on the increase in labour force participation among women and that the reduction in fathers’ work hours was not taken into account in analyses of the economic impact of child care funding.41 According to economist Pierre Fortin, while the increase in labour force participation among women in general is not entirely related to child care funding, most of the increase among women aged 20 to 44 can be explained by this reform.42 In 2018, a Statistics Canada study reaffirmed this link between the increased participation in the labour force among Quebec mothers with children under 13 and the province’s family policies, particularly with respect to affordable child care.43

For many years, various stakeholders have been calling on the federal government to help create a national system for early childhood education and care. As we have seen, each province and territory currently has its own system with varying degrees of accessibility and affordability, creating a patchwork of child care programs across the country.

Although a consensus on the exact form this system should take has not been reached, some broad guidelines have emerged:

With respect to funding, most stakeholders agree that it would be beneficial for the federal government to increase its investments in early childhood education and care. The minimum level of spending on early childhood education and care recommended by organizations like the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) is 1% of the gross domestic product (GDP). Although the proportion of the GDP that Canada allocates to it has not been formally calculated since 2006, observers agree that it remains well below 1%, one of the lowest figures among OECD countries.45 Various stakeholders consider that Canada will need to address a shortfall of up to $8 billion per year if it is to achieve the OECD’s average rate of 70% participation in early childhood education for children aged 0 to 5 (Canada’s rate was 53% in 2017). These stakeholders recommend increasing federal government spending by $1 billion to $2 billion every year until this gap is closed.46

The universality of a potential national system of educational child care services is a matter of debate. Some argue that publicly funded early childhood education and care programs are more cost-effective in terms of economic returns when they specifically target groups of children who are disadvantaged or at risk of developmental delays. Others argue that mixing children from different backgrounds ensures that all children have access to the same quality of services, and leads to positive effects among peers.47 In addition, universal programs may have the advantage of not excluding certain vulnerable populations, avoiding the stigma associated with programs for vulnerable families thereby increasing participation by these families, and providing some administrative efficiencies as a result of not having to check eligibility criteria.48

The question of a legislated right given to all children concerning access to early childhood education is a frequently recurring one. In several European countries, all children, upon reaching a specific age, are entitled to a certain number of hours of non-mandatory early childhood education, regardless of their parents’ occupation or income. According to some stakeholders, granting such a right to children in Canada would standardize access to early childhood education, emphasize its educational nature and protect such an acquired right from future policy changes.49

As noted above, the federal government has recently stated that it wants to develop a national system of educational child care services that draws on the model used in Quebec.50 As we have seen, the Quebec model has been very successful in terms of women’s participation in the labour force, and over the past two decades, in terms of creating nearly 100,000 spaces in CPEs which generally provide quality, affordable educational services to young children. However, many observers point out that the quality of services in the other two-thirds of the child care system is uneven and generally lower, where children from disadvantaged backgrounds are over-represented. Some experts applaud the direction Quebec took in the late 1990s to invest heavily to fund affordable child care spaces in non-profit centres. However, they caution against what they call the “transition problems” associated with implementing such an ambitious plan across the country. The difficulties the Quebec government encountered in creating sufficient CPE spaces and the alternatives put forward by successive governments have had undesired effects on the quality of educational services that some children receive. These experts recommend that the federal government develop a detailed, evidence-based implementation plan that it will carry out at a pace that ensures the development of quality services for Canadian families.51

† Library of Parliament Background Papers provide in-depth studies of policy issues. They feature historical background, current information and references, and many anticipate the emergence of the issues they examine. They are prepared by the Parliamentary Information and Research Service, which carries out research for and provides information and analysis to parliamentarians and Senate and House of Commons committees and parliamentary associations in an objective, impartial manner. [ Return to text ]

© Library of Parliament