The COVID‑19 pandemic drove many legislatures around the world to adopt or expand their use of digital technologies in order to continue exercising their core functions of legislating, studying issues of public policy, scrutinizing governments and representing constituents. In the face of physical distancing requirements and lockdowns, the Parliament of Canada introduced new information and communication technology (ICT) – such as Zoom and, in the House of Commons, a new electronic voting system – to increase its capacity to hold remote and hybrid chamber and committee meetings. Senators and members of Parliament had to adapt quickly to participate in Parliament remotely and to engage with each other, with citizens and with stakeholders in an increasingly digital environment.

This HillStudy examines the experiences of Canadian senators, members of Parliament and parliamentary staff with digital parliament since the pandemic. It places these experiences in a wider context of those had by parliamentarians and parliamentary staff in other countries and jurisdictions – especially the ones that adapted ICT to fit similar Westminster traditions and procedures. It also highlights recent research by academics, the Samara Centre and the Inter-Parliamentary Union on the possible effects of digital parliaments on core parliamentary functions.

On 5 May 2023, the World Health Organization declared that COVID‑19 was no longer “a public health emergency of international concern.”1 By this time, parliaments around the world had begun to ease physical distancing rules and other measures to mitigate the spread of the disease.

Many legislatures exited the COVID‑19 pandemic (the pandemic) transformed by new or expanded information and communication technology (ICT). The pandemic had driven many parliaments to adopt or expand their use of ICT to continue exercising their traditional functions of legislating and deliberating, scrutinizing governments and representing constituents. In Canada, Parliament introduced ICT – such as Zoom videoconferencing software, and, in the House of Commons, a new electronic voting system – to increase its capacity for holding remote and hybrid chamber and committee meetings. Canadian senators and members of Parliament (MPs) adapted quickly to working in an increasingly hybrid environment, and Parliament has since expanded its digital services.

This HillStudy examines the experiences of Canadian senators, MPs and parliamentary staff with digital parliament2 during and after the pandemic, as well as the experiences of politicians and staff in other Westminster-style parliaments and other legislatures around the world. It outlines the benefits and challenges of introducing and expanding the use of these technologies. It also articulates possible principles by which to evaluate what adaptations – if any – to keep or expand upon now that the pandemic is no longer a global emergency.

Scholars of Westminster-style parliaments, such as those in Canada, the United Kingdom (U.K.), Australia and New Zealand, generally agree on a parliament’s three core functions:3

Before 2020, few parliaments allowed virtual or hybrid plenary sessions and committee meetings for parliamentarians. By the end of that year, however, one‑third of legislatures surveyed by the Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU) reported having held a virtual or hybrid plenary (or “main chamber”) session, and 65% reported having held virtual or hybrid committee meetings.8

New ICT continues to be adopted since the pandemic emergency ended. Among the legislatures that IPU surveyed between October 2023 and January 2024, 45% supported remote or hybrid plenary sessions, and 52% supported remote or hybrid committee meetings.9 One-fifth also allowed parliamentarians to vote remotely in plenary sessions, which is roughly double the number in 2020.10 Many parliaments, especially upper-middle and high income parliaments, have also expanded or adopted less visible forms of ICT, such as electronic voting, citizenship engagement platforms, cloud computing, more comprehensive and accessible public data, digital document management systems for parliamentary documents and artificial intelligence.11

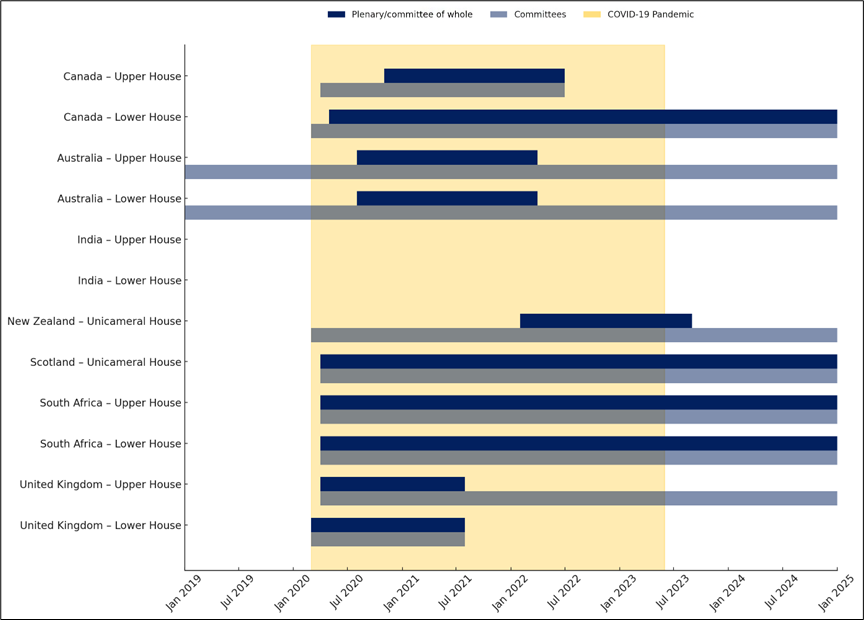

At the same time, while largely increasing the use of ICT to support parliamentary processes, parliaments have also made different choices with respect to remote participation in plenary sessions and meetings of the committee of the whole. Among select Westminster parliaments, the Canadian House of Commons, the Scottish Parliament, and both upper and lower South African houses allow remote participation in plenary sessions or committee-of-the-whole meetings. Conversely, the Canadian Senate, both upper and lower U.K. and Australian houses, and the New Zealand House of Representatives no longer do. While it introduced other significant ICT during the pandemic, such as an electronic voting system,12 the Parliament of India chose to use in-person social distancing measures rather than measures to allow remote and hybrid participation (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 - Enabling Remote Participation in Select Westminster Parliaments During and After the COVID‑19 Pandemic, from January 2019 to January 2025

Note: This chart treats as continuous any short lapse (less than three months) in regulations allowing remote participation during a parliamentary recess or between parliaments.

Sources: Senate, Journals, 11 April 2020; Senate, Journals, 27 October 2020; Senate, Debates, 3 November 2020; Senate, Journals, 31 March 2022; Senate, Journals, 5 May 2022; House of Commons, Journals, 20 April 2020; House of Commons, Journals, 24 March 2020; House of Commons, Journals, 23 September 2020; United Kingdom, House of Lords Library, House of Lords: timeline of response to Covid-19 pandemic, 1 March 2022; Parliament of the Republic of South Africa, National Council of Provinces, “Rules of Virtual Meetings And Sittings,” Announcements, Tablings and Committee Reports ![]() (278 KB, 5 pages), Second Session, Sixth Parliament, 20 April 2020; Parliament of the Republic of South Africa, Rules for Virtual Parliament Meetings, News release, 22 April 2020; Parliament of the Republic of South Africa, National Assembly, “Rule on Virtual Meetings in terms of National Assembly Rule 6 (Unforeseen Eventualities),” Announcements, Tablings and Committee Reports

(278 KB, 5 pages), Second Session, Sixth Parliament, 20 April 2020; Parliament of the Republic of South Africa, Rules for Virtual Parliament Meetings, News release, 22 April 2020; Parliament of the Republic of South Africa, National Assembly, “Rule on Virtual Meetings in terms of National Assembly Rule 6 (Unforeseen Eventualities),” Announcements, Tablings and Committee Reports ![]() (285 KB, 3 pages), Second Session, Sixth Parliament, 15 April 2020; Inter-Parliamentary Union, Association of Secretaries General of Parliaments, Covid 19: The Parliamentary hybrid plenary uptake, and electronic voting challenges

(285 KB, 3 pages), Second Session, Sixth Parliament, 15 April 2020; Inter-Parliamentary Union, Association of Secretaries General of Parliaments, Covid 19: The Parliamentary hybrid plenary uptake, and electronic voting challenges ![]() (173 KB, 9 pages), Communication by Baby Penelope Tyawa, Acting Secretary to Parliament of the Republic of South Africa, Spring session, 26–27 May 2021; Parliament of Australia, Australia’s Parliament House in 2021: a Chronology of Events, 1 April 2022; Parliament of Australia, Australia’s Parliament House in 2022: a Chronology of Parliament, 3 April 2023; Parliament of Australia, Stephanie Gill, “Can you hear me? Remote participation in the Commonwealth Parliament,” Flagpost, 19 July 2022; Scottish Parliament, Sarah McKay and Courtney Aitken, How has the COVID‑19 pandemic changed the way the Scottish Parliament works?, SPICe Briefing, 7 December 2021; Parliament of New Zealand, How Parliament responded to the pandemic; Parliament of New Zealand, Standing Orders Committee, Review of Standing Orders 2023

(173 KB, 9 pages), Communication by Baby Penelope Tyawa, Acting Secretary to Parliament of the Republic of South Africa, Spring session, 26–27 May 2021; Parliament of Australia, Australia’s Parliament House in 2021: a Chronology of Events, 1 April 2022; Parliament of Australia, Australia’s Parliament House in 2022: a Chronology of Parliament, 3 April 2023; Parliament of Australia, Stephanie Gill, “Can you hear me? Remote participation in the Commonwealth Parliament,” Flagpost, 19 July 2022; Scottish Parliament, Sarah McKay and Courtney Aitken, How has the COVID‑19 pandemic changed the way the Scottish Parliament works?, SPICe Briefing, 7 December 2021; Parliament of New Zealand, How Parliament responded to the pandemic; Parliament of New Zealand, Standing Orders Committee, Review of Standing Orders 2023 ![]() (1.49 MB, 107 pages), August 2023, p. 15; Parliament of New Zealand, “Standing Orders,” Debates, 31 August 2023; Inter-Parliamentary Union, Association of Secretaries General of Parliaments, “Communication from Shri Sumant Narain, Joint Secretary of the Rajya Sabha of India, ‘How have parliaments changed since the pandemic,’” Constitutional & Parliamentary Information

(1.49 MB, 107 pages), August 2023, p. 15; Parliament of New Zealand, “Standing Orders,” Debates, 31 August 2023; Inter-Parliamentary Union, Association of Secretaries General of Parliaments, “Communication from Shri Sumant Narain, Joint Secretary of the Rajya Sabha of India, ‘How have parliaments changed since the pandemic,’” Constitutional & Parliamentary Information ![]() (1.77 MB, 107 pages), 24–26 October 2023, pp. 100–104; and “Presiding officers saying no to virtual meetings of Parliamentary standing committees disappointing: Chidambaram,” Times of India, 15 May 2021.

(1.77 MB, 107 pages), 24–26 October 2023, pp. 100–104; and “Presiding officers saying no to virtual meetings of Parliamentary standing committees disappointing: Chidambaram,” Times of India, 15 May 2021.

Like many foreign parliaments, the Parliament of Canada chose to retain some forms of remote participation after the pandemic.

The new ICT adopted is built on pre-pandemic infrastructure and practices. Prior to the pandemic, Parliament used ICT to support chamber and committee meetings. For instance, both the Senate and the House of Commons allowed up to four committee witnesses at a time to testify remotely via specially equipped videoconferencing studios, available to witnesses at different locations.13

More recently, the House of Commons introduced more institutional ICT resources for individual parliamentarians and administration employees, “to enable all House Administration employees to stay in touch with the organisation network from anywhere, at any time.” 14

For Canada’s Parliament, its parliamentarians and parliamentary staff, the pandemic caused the adoption of ICT to increase exponentially. On 13 March 2020, the Senate and the House of Commons extended the end date of a planned March adjournment in response to the outbreak of the pandemic and subsequent lockdown in Canada.15 After the dangers of COVID‑19 became clearer, the House of Commons was recalled on 24 March 2020, as was the Senate a day later, to consider legislation.16

On 24 March 2020, the House of Commons adopted a motion empowering the Standing Committee on Health and the Standing Committee on Finance to meet by teleconference or videoconference, under expanded mandates, “for the sole purpose of receiving evidence concerning matters related to the government’s response to the COVID‑19 pandemic.” 17 These committee meetings were the first in which all MPs and witnesses participated remotely. The committees met first by teleconference, then beginning 9 April 2020, by videoconference.18

On 11 April 2020, the Senate and the House of Commons were again briefly recalled to consider legislation. At this point, the Senate gave three committees the power to meet by teleconference or videoconference, and, on 14 April 2020, the first completely virtual Senate committee was convened.19 The House of Commons added new committees to the list of committees allowed to meet virtually.20

On 20 April 2020, the House of Commons was briefly recalled again. At that time, it created a special committee composed of all MPs to examine Canada’s response to the pandemic. At the outset, the special committee on the pandemic met in person once a week with a reduced number of members, and once a week in hybrid format; After 7 May 2020, it met three times per week, twice in hybrid format, with the vast majority of members participating virtually.21

To make sure that all parliamentarians could participate in committees – including in the new all-party committee on the pandemic – the Senate and House of Commons administrations inventoried each parliamentarian’s ICT and shipped them any missing equipment they needed to attend a virtual session, such as headsets.22 They also worked to integrate Zoom videoconferencing software into existing infrastructure. The platform was chosen for hosting public virtual meetings because it offered sufficient security features and had the capacity to incorporate simultaneous interpretation and broadcasting.23

In September 2020, the House of Commons resumed sittings using a hybrid format. This format combined videoconferencing with in-person attendance by MPs for both House and committee meetings. It also allowed MPs, during recorded divisions, to vote in person by rising in their seats, or to vote via videoconference by stating on camera: “I vote in favour of the motion” or “I vote against the motion.”24

On 27 October 2020, the Senate agreed on similar hybrid measures for its proceedings, and on 17 November 2020, it began allowing all committees to meet either in hybrid format or through videoconference only, subject to technological feasibility. In addition to authorizing in-person voting, the Senate permitted senators to vote by holding up cards indicating “yea,” “nay” or an abstention by videoconference, a system that reduced confusion and minimized the additional time required for votes.25

On 25 January 2021, the House of Commons adopted a motion to use a remote voting system, pending training, simulations and agreement by the party whips. The electronic voting system took the form of an application installed on members’ devices. It was first used on 8 March 2021 and is designed to work concurrently with in-person voting. Among other security measures it relies on, the system uses multi‑factor authentication which includes facial recognition software to confirm the visual identity of the member who is inputting their vote. This system reduced voting time in hybrid conditions from an average of about 45 minutes per vote to between 12 and 15 minutes per vote.26 Prior to the pandemic, recorded votes in person only took approximately 10 minutes.27

When the 1st Session of the 44th Parliament began on 22 November 2021, the House of Commons again agreed to allow hybrid chamber meetings, hybrid committee meetings and remote voting.28 On 23 June 2022, it extended these measures and the related procedural changes until 23 June 2023 by adopting a similar motion – one that also directed the Standing Committee on Procedure and House Affairs (PROC) to study hybrid proceedings in the House of Commons.29 On 7 December 2021, the House of Commons agreed to give members, senators and departmental and parliamentary officials the option to appear in person as committee witnesses.30 It extended this option to all witnesses on 6 April 2022.31

On 30 January 2023, PROC presented its 20th report, Future of Hybrid Proceedings in the House of Commons, to the House. Its recommendations included, among others, continuing hybrid Parliament and requiring chairs and vice-chairs to appear in person for committee meetings. PROC also recommended that “it be a best practice for members of Cabinet to be present in person to answer questions during question period and to testify before committees.” 32 On 15 June 2023, the House of Commons voted to make hybrid measures a permanent part of the Standing Orders, starting 24 June 2023.33 This change included a new requirement for committee chairs to appear in person at all committee meetings.34

At the beginning of the 1st Session of the 44th Parliament in November 2021, the Senate similarly agreed to motions allowing hybrid plenary sessions and committee meetings, and voting while participating over videoconference.35 Through motions passed on 31 March 2022 and 5 May 2022, it extended these hybrid measures to the end of June 2022.36 After that time, the Senate and Senate committees started to meet exclusively in person, and they continue to do so now; only witnesses have the option of appearing by videoconference. The only exceptions are hybrid meetings of the joint Senate–House of Commons committee, which the Senate, through sessional orders, agreed to allow, and Senate subcommittee meetings.37

Adapting to the pandemic brought to light both the opportunities and the challenges that arise in realizing traditional parliamentary ideals through ICT.

The clearest signs of having successfully adopted ICT come at the operational level. During the pandemic, parliaments around the world successfully used remote technology to legislate and scrutinize government operation and policy, despite the sharp learning curve, differences in Internet speeds, unequal access to the Internet among countries and technical glitches. As Lord Norton of the U.K. House of Lords put it, “[t]he technology represents a success story, one unachievable had the crisis occurred some decades ago. It has enabled the House [of Lords] to function.” 38 Parliamentarians and experts in Canada and the IPU argue that this increased capacity has made legislatures more resilient to disruption by future emergencies.39

Remote parliamentary work also helps to increase the representation of a more diverse set of interests and perspectives. Parliamentarians in Canada and abroad have noted that digital parliament facilitates the participation of Parliamentarians who have childcare commitments or medical vulnerabilities. It allows legislators who are located far from a legislature to contribute more easily and with less disruption in their parliamentary work and family lives.40 It also reduces the legislators’ travel and gives them more time among their constituents.41 Experts in Canada and the U.K. argue that this increased flexibility enables legislatures to draw from a wider pool of candidates – people who might otherwise find it very difficult to participate in politics.42 Some experts argue that greater representation improves the ability of Parliament to make and scrutinize legislation, because parliamentarians draw from a more diverse range of experiences.43

In committee work, remote communication platforms may increase representation in some countries by facilitating greater witness diversity and expertise. Observers in the U.K. and Canada have suggested that people from farther away and with less ability to travel can participate virtually more easily.44 Witnesses may feel less intimidated about testifying online than they would in person and they may find it more convenient to testify on short notice.45 Moreover, it has been argued that greater witness diversity and expertise improve the ability of legislators to oversee the government and hold it to account.46

Additionally, virtual work allows legislators to increase linkages with other governing bodies, interest groups and constituents, as it enables them to connect directly via Zoom or MS Teams.47 At the outset of the pandemic, 55% of MPs in Canada reported an increase in the use of Facebook, and 42% mentioned an uptick in the use of interactive live videos.48 Five years later, the Honourable Greg Fergus, Speaker of the House of Commons, noted that

many Canadian Members of Parliament are avid social media creators. They use social media platforms to engage directly and effectively with the electorate to raise awareness about parliamentary matters, in real time and unmediated by journalists. The format of social media also allows MPs to curate the proceedings of the House of Commons for political and fundraising purposes.49

Lastly, remote work decreases the cost of Parliament because parliamentarians travel much less. In a large country like Canada, the savings are substantial because many parliamentarians must travel by air. In their 25 February 2021 report, the Parliamentary Budget Officer estimated the costs and savings of a hybrid parliamentary system in Canada if attendance in Parliament were to continue as observed since 5 December 2019, the beginning of the 2nd Session of the 43rd Parliament. Measured against this benchmark, Parliament would save $6.2 million annually and reduce its greenhouse gas emissions related to travel by about 2,972 metric tons of CO2 equivalent.50

Many of the immediate challenges parliamentarians face with increased remote work mirror those encountered by people in other fields: fatigue, reduced trust, less spontaneity, the higher likelihood of misinterpretation and the reduced transfer of institutional culture.

“Zoom fatigue,” the disproportionately exhausting effect of meeting by videoconference compared with meeting in person, has been widely documented and discussed. Psychologists point to the way these platforms distort in-person social conventions. Videoconferencing demands unnaturally long periods of close eye contact, seeing oneself on camera for whole meetings and reduced mobility. It also communicates less information, particularly given the absence of body language, which makes the motivations and actions of others more ambiguous.51 Research suggests that people find it more difficult to develop trust if they interact mainly online.52 They also struggle to perceive and maintain an organization’s structure and working culture.53 As well, the strict technical and social conventions of videoconferencing and instant messaging do not lend themselves to spontaneous, informal interactions that can promote unity, encourage information sharing and spark new ideas. People find it harder to chat informally with acquaintances if they need to make an appointment or send a message to a particular address.54

While they communicated largely online in the parliamentary sphere early in the pandemic, parliamentarians, journalists, staff and citizens from Canada and the U.K. similarly complained of difficulty reading the body language of ministers, other parliamentarians, witnesses and staff. They felt there was less unity and trust among parliamentarians because of a lack of ongoing contact. They also felt there was less spontaneity in all interactions and more technical and procedural rules governing those interactions.55 More recently – addressing both fully remote and hybrid participation – some Canadian MPs commented that virtual participation makes it more difficult to build morale and camaraderie among caucus members, and harder to find compromise and develop trust with members of other parties.56

Early in the pandemic, Canadian officials also highlighted the fact that simultaneous interpretation of French and English – Canada’s two official languages – requires sufficiently clear audio quality.57 Presenters at a conference of the Canadian Study of Parliament Group (CSPG) in March 2021 noted that parliamentary meetings in Canada are particularly vulnerable to the many technical disruptions that affect audio and interpretation capacity.58

Despite evolving measures to protect interpreters, such as audio and technical tests with members and witnesses ahead of meetings, from March 2020 to September 2022 interpreters submitted to their employer, the Translation Bureau, about 90 incident reports raising health and safety concerns. Thirty percent of these reports involved a temporarily disabling injury.59 In response, and following two rulings from the Labour Program and several sound quality studies, the Translation Bureau introduced improved models of headsets required for use by witnesses; updated audio equipment (e.g., ear pieces, Larsen-effect prevention devices) for members participating in person; and new rules and committee signage for their use.60 Working with the Senate and House administrations and committee officials, the organization also introduced non-technical measures, such as assigning a technician to support each meeting in which simultaneous interpretation was provided.61 In the last year, the number of reports of health and safety risks made by interpreters was much lower (less than 1%); most of the incidents reported were caused by human error.62

Lastly, parliamentarians must deal with scheduling constraints due to the technical requirements for interpretation. To mitigate the risks associated with interpreting online audio with variable sound quality of, interpreters have limits on the length of time they may work during hybrid meetings.63 They work in blocks of time according to the terms and conditions of their work agreements. Depending on the availability of interpreters to support all meetings and events, committees may run into limits when requesting additional time to extend meetings or to meet in a new or additional time slot (although, since 2024, the regular use of simultaneous interpretation by additional interpreters working remotely has supplemented this capacity, allowing some meetings to be extended).64 Additionally, witnesses sometimes cannot be scheduled on short notice, because they require time to obtain or receive the mandatory high‑quality headset.65

In the Westminster parliamentary context, increased workload and fatigue, reduced trust, greater risk of misinterpretation, less spontaneity and technical difficulties can have negative effects on fulfilling parliamentary functions, in addition to creating general challenges.

The risks to the scrutiny function are clear. Since the beginning of the pandemic, parliamentarians, officials and academics have argued that ministers from Canada and the U.K. made speeches by videoconference with less oversight and under less pressure, because they could not read the mood of a parliamentary chamber or committee room, and they could not feel the mood shift against them. As well, members could not ask pointed questions as easily, because they had fewer opportunities for spontaneity and fewer occasions to build alliances with other members.66

Similarly, the mediation of ICT can undermine the quality of Parliamentary deliberation and oversight. Speaking in March 2021 at a CSPG conference, Canadian parliamentarians noted that members in committee and in Parliament were less likely to work out an issue and come to new conclusions over email, text and videoconference, because they lacked opportunities for spontaneous informal discussion. Lucinda Maer, Deputy Principal Clerk in the U.K. House of Commons, described a similar effect of Zoom on U.K. committee negotiations:

Members may speak in bilateral calls or by text message after the committee but unlike in the committee room where you can watch alliances form or disagreements continue – this is all invisible to those not included in the call or messaging group.67

Some evidence suggests that remote and hybrid work may change the dynamics of legislating. While remote voting makes it easier to combine voting with fulfilling other parliamentary responsibilities, like committee and constituency work, it may also make it harder for parliamentarians to resolve issues or find compromise, according to anecdotal reports by parliamentary clerks for the parliaments of the U.K. Crown Dependencies: Guernsey, Jersey and the Isle of Man. For example, “on two separate occasions in the Isle of Man, a set of emergency regulations was lost on a division,” a rare occurrence in that parliament. The clerks suggested that the legislation was not passed because “[m]embers could not gather in the margins of a debate to resolve differences, agree to compromises and do the business of politics.” 68 Canadian and Irish MPs similarly have complained that networking with colleagues, advocating positions and finding compromise are difficult in hybrid conditions.69

While an increased online presence can enhance connections with many groups of people, digital parliament can also undermine representation. Canadian parliamentarians, witnesses and constituents living in rural and northern regions often lack the same access to high-speed and reliable Internet enjoyed by people living in urban and southern Canada. It may also take longer for these committee witnesses to receive or acquire their mandatory headsets.70 These differences can make participation in online parliament more difficult for some populations.71

As well, several Canadian MPs have recounted being less able to represent constituent interests when participating online. Videoconference meetings largely eliminate informal “water cooler” talk with other MPs that allows them to bend the ear of a colleague or minister on a constituent issue.72 As one MP put it in an anonymous research interview conducted on 1 May 2021, digital parliament has “been limiting because a lot of work is done informally in terms of raising issues, causes, and concerns of your constituents just by sort of impromptu conversations with different ministers, whether that’s in caucus or in the lobby.” 73 This point was echoed by several U.K. MPs, who lamented the loss of informal, in-person access to ministers in Parliament and to the prime minister, to represent constituents’ concerns.

Hybrid parliaments can also create inequalities between parliamentarians participating in person and those participating online.74 In addition, less informal contact and weaker social connections between parliamentarians mean that they are increasingly receiving information from party whips. This dynamic centralizes power in party hierarchies and may decrease the diversity of views.75

While the pandemic prompted parliaments to introduce various innovations, many parliaments are advocating for and experimenting with even greater ICT use.

Advocates of ICT often argue that it has the potential to contribute to the legislative function of representation, and its related ideal of transparency, in particular. They claim that the more parliamentary data, reports and debates are available electronically, the more this information may be accessed by citizens and parliamentarians. And the more a parliament integrates social media and software that allows two-way communication, the more citizens may be able to engage with parliamentarians and parliaments directly.76

Some legislatures are developing this two-way engagement with citizens using both old and new ICT. Canada and the U.K. have increased citizens’ ability to engage with MPs through e‑petitions.77 Some MPs in the U.K. are using artificial intelligence (AI) to discern trends on social media in citizens’ views on certain issues. Some parliaments are also studying the use of AI to triage constituent inquiries and to develop a chatbot to help constituents find legislative information online.78 The Parliament of India is currently experimenting with AI to tag metadata in audiovisual recordings of Parliamentary proceedings, making them easily searchable by the public.79

Other innovations have occurred in the areas of legislating and scrutinizing. For instance, the Chamber of Deputies of Chile developed a digital platform that combines a suite of AI legislative assistants which enhances “the Chamber’s ability to manage legal texts, financial oversight, and parliamentary assignments.” 80 The first module – the legislative module – includes AI assistants that can provide legislators with:

In the wake of the pandemic and the concurrent increase in the rate at which ICT is adopted, parliaments must assess each ICT according to parliamentary ideals and citizen expectations. Some researchers and parliamentarians who study ICT have suggested principles for assessing the risk and benefits:

[t]here being no perfect solution, trying to find one may stall progress. In Chile, rather than attempt perfection, the Chamber of Deputies delivered a “minimum viable product,” adding functionality or fixing bugs through iterative releases later, as solutions emerged in the live environment.88

Ultimately, the rise in adopting ICT since the beginning of the pandemic has presented parliaments and parliamentarians with new choices for maintaining and developing parliament as an institution. Compared to pre-pandemic technological adaptation, using this technology or expanding its use is much easier. Many parliamentarians and staff are comfortable with using ICT to work remotely. Citizens are also increasingly accustomed to online engagement.

At the same time, ICT can alter the political and interpersonal dynamics that animate a parliament’s core functions of legislation, scrutiny and representation. Historically, parliamentary practices were developed through face-to-face debate and conversation, reflecting the long-standing procedures and conventions of the parliamentary cycle, rather than those of videoconferencing or electronic voting. Drawing from the pandemic experience, parliaments are in a better position to decide which forms of ICT, if any, to maintain and develop in the future, and how best to use them.

© Library of Parliament