Canada’s multi-billion-dollar tourism sector employs hundreds of thousands of Canadians and is supported by all levels of government.

In 2020, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, global tourism and travel sector revenue decreased by 49% from the previous year, to US$4.7 trillion. Global tourism employment fell by 19% to 272 million jobs. Similarly, the Canadian sector earned $49.5 billion in 2020, a decline of 40% from 2019, while domestic employment fell to 1.6 million direct and indirect jobs, a decrease of 24%. About 28% of Canadian tourism revenue is generated from inbound visits.

In 2019, Canadians made 37.8 million foreign trips consisting mainly of 27.1 million visits to the United States. Additionally, Canadians made 10.7 million trips to other countries, most frequently Mexico (1.8 million), Cuba (964,000), the United Kingdom (770,000), China (666,000) and Italy (619,000).

According to the World Economic Forum’s Travel & Tourism Competitiveness Report 2019, which ranks the most competitive countries for travel and tourism, Canada ranked ninth out of 140 countries studied, down from eighth place in 2013. Canada ranked first in several sub-categories, such as safety and security, environmental sustainability and air transport infrastructure. Conversely, Canada was found to be deficient in several areas, including price competitiveness and international openness.

Other studies have found that tourism demand is concentrated in Canada’s largest cities, with Toronto, Vancouver and Montréal accounting for 75% of overall visitors and most of this activity taking place during the summer months. There are also challenges stemming from labour shortages, a lack of investment and promotion, and a lack of coordination of tourism policy between all levels of government.

Destination Canada (formerly the Canadian Tourism Commission) is a federal Crown corporation responsible for national tourism marketing and is governed by the Canadian Tourism Commission Act. In 2019, the federal government announced Creating Middle Class Jobs: A Federal Tourism Growth Strategy, which is based on the following three pillars: building tourism in Canada’s communities; attracting investment to the visitor economy; and renewing the focus on public-private collaboration.

Between 2008 and 2020, the federal government invested approximately $1 billion in the tourism industry. In 2021, it announced another $1 billion in funding, including the Tourism Relief Fund.

If international borders continue to reopen and the industry continues its steady overall growth of the recent years prior to the pandemic, it will again contribute to Canada’s economic well-being. And although the United States continues to be Canada’s biggest tourism trading partner, stakeholders might continue their efforts of focusing on more growth-oriented, lucrative emerging markets to better diversify tourism interests to help Canada fulfil its tourism potential.

Canada’s tourism industry is an important contributor to Canadian economic growth. This industry – which comprises hospitality and travel services to and from Canada – is a multi-billion-dollar business that employs hundreds of thousands of Canadians and is supported by all levels of government. This HillStudy provides information about Canada’s tourism industry, travel patterns of visitors to and from Canada, the importance of the United States (U.S.) to Canada’s tourism economy and the role of the federal government.

The global tourism sector suffered substantial declines in activity due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Since this HillStudy incorporates data from 2019 and 2020, special attention should be paid to both explicit tourism figures and relative comparisons to previous years due to the extraordinary effects of the pandemic.

According to the Tourism Industry Association of Canada, “travel and tourism” includes “transportation, accommodations, food and beverage, meetings and events, and attractions,” such as festivals, historical/cultural institutions, theme parks and nature settings.1

The World Travel & Tourism Council’s latest annual research explains the COVID 19 pandemic’s impact on the global travel and tourism sector:

Only about 28% of Canadian tourism revenue (about $21.3 billion) is generated from inbound visits. The remainder represents domestic spending – i.e., what Canadians spend on domestic and foreign tourism activities. Table 1 provides further information about the industry’s recent performance.

| Category | 2019 | 2020 | Change (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Domestic spending | $82 billion | $49.5 billion | -40% |

| International spending | $21.3 billion | $4 billion | -81% |

| Jobs directly supported by tourism | 748,000 | 533,000 | -29% |

| Total tourism employment | 2.1 million | 1.6 million | -24% |

| Number of tourism establishments | 232,000 | Not available | Not available |

| Tourism GDP | $43.7 billion | $22 billion | -50% |

| Tourism’s share of Canada’s GDP | 2.02% | 1.06% | -48% |

Note: Domestic spending includes spending while on a trip in Canada, spending on airfares with Canadian carriers on outbound trips and spending on tourism-related goods, e.g., camping equipment. International spending includes spending while on a trip in Canada but excludes any pre-trip purchases. GDP refers to gross domestic product.

Source: Table prepared by the Library of Parliament using data obtained from Destination Canada, Canada Tourism Fact Sheet 2020 ![]() (446 KB, 2 pages).

(446 KB, 2 pages).

There are two ways to categorize jobs in tourism:

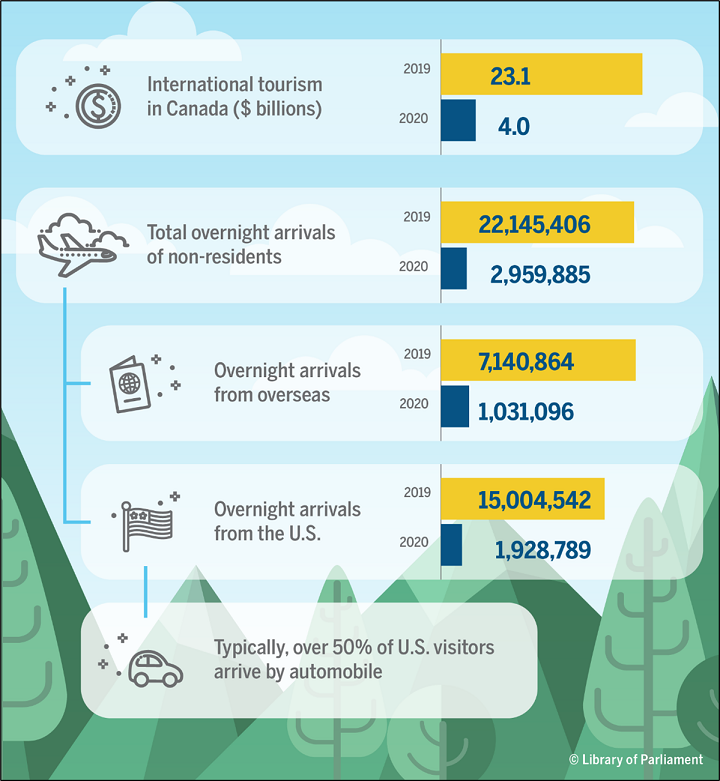

Figure 1 provides further details about international arrivals to Canada.

Figure 1 – Selected Information on International Arrivals to Canada

Source: Figure prepared by the Library of Parliament using data obtained from Destination Canada, Canada Tourism Fact Sheet 2020 ![]() (446 KB, 2 pages).

(446 KB, 2 pages).

According to Destination Canada, prior to the pandemic, Canada benefited from the fact that the tourism sector was booming globally. Since 2000, tourism has been growing approximately three to four times faster than the global population and about 1.5 times faster than the overall global GDP. Furthermore, notwithstanding the COVID-19 pandemic, this was expected to continue into the mid-2020s. In fact, 2017’s travel and tourism sector growth of 4.6% exceeded the global GDP growth rate of 3.7%; that is, for the seventh successive year, the sector outpaced global GDP growth, which itself had the strongest growth a decade.3

However, even with this strong performance, Canada’s tourism industry potential remains significantly underdeveloped. Specifically, even though it has outpaced global population and GDP growth, Canadian tourism growth has lagged behind global tourism growth for several years (see section 3.6 of this Hill Study).4

Moreover, tourism represents a much smaller fraction of Canada’s exports when compared to peer countries such as the U.S., Japan, the United Kingdom and Australia. Studies suggest there is an opportunity for Canada to more than double its international arrivals and associated revenues by 2030.5 This could be achieved, in part, by capitalizing on “substantial opportunities to increase the number of tourists to Canada from the United Kingdom, China, France, Germany and Australia.”6

Beyond its role in helping to create revenue and both direct and indirect jobs in the Canadian tourism industry, the efficient promotion of tourism can be seen as a valuable investment in Canada’s overall economy. A 2013 Deloitte study has shown that “a rise in business or leisure travel between countries can be linked to subsequent increases in export volumes to the visitors’ countries.”7

In 2019, the Canadian tourism sector had its best year on record, reaching 22.1 million international overnight arrivals, a 4.8% increase over the previous year. Similar to other years, the vast majority (67.7%) came from the U.S.; the top three non-U.S. sources of visitors were the U.K. (875,632), China (715,474) and France (668,490).8

Destination Canada reported that “air and sea arrivals from the Europe region were mostly on par with 2018 levels, with the exception of France, which led the region (+7.0%).”9 However, there were mixed results from the Asia-Pacific region as the biggest decline came from the region’s largest market, China (-9.1% in air and sea arrivals), with smaller downward trends from Japan (-1.9%) and Australia (-0.4%). More positively, air and sea arrivals from South Korea were slightly ahead of 2018 levels, while India led the region in year-over-year growth (+9.1%).10

In North America, the U.S. provided an increase in arrivals on overnight trips entering Canada by air and auto of 6.4%. Mexico was the only one of Destination Canada’s long-haul markets to record double-digit year-over-year growth in overnight arrivals by air and sea (12.3%) in 2019.11

Canada’s rising popularity among Chinese travellers is particularly noteworthy, as China is now Canada’s second-largest overseas tourism source after the U.K.12 This is partly attributable to Canada’s having been granted Approved Destination Status by the Chinese government. In 2018, Canada welcomed a record 737,000 Chinese tourists, “surpassing the 700K mark for the first time and doubling the number of annual travellers since 2013, with an average annual growth rate of 16%.”13 Travelling mainly during July and August, “Chinese tourists spend on average about $2,850 per trip to Canada, staying for around 30 nights.”14

In 2019, Canadians made 37.8 million foreign trips consisting mainly of 27.1 million visits to the U.S. Although travel to the U.S. declined by 2.3% in 2019 compared to 2018, Canadians “spent $21.1 billion on their trips to the United States in 2019, up 4.8% from a year earlier.”15

Additionally, Canadians made 10.7 million trips to other countries, the most common of which were Mexico (1.8 million), Cuba (964,000), the U.K. (770,000), China (666,000) and Italy (619,000).16

Canadians also enjoy travelling within the country, making 275 million domestic trips in 2019, down 1.0% from 2018. Spending on trips within Canada declined 0.3% year over year to $45.9 billion.17 The top locations were Ontario (116.5 million visits), Quebec (56.9 million visits), British Columbia (34.2 million) and Alberta (32.4 million); this includes both intra and inter-provincial/territorial domestic travel.18

Canada’s Indigenous tourism sector is diverse and comprises different business models. Although its key drivers of employment and GDP come from air transportation and resort casinos, “it is the cultural workers, such as Elders and knowledge keepers, who define many of the authentic Indigenous cultural experiences available to tourists in Canada.”19 Moreover, when compared with Indigenous tourism enterprises without a cultural focus, those involved in cultural tourism rely more on visitors from foreign markets as part of their customer base.

Prior to the pandemic, Canada’s Indigenous tourism sector had been rapidly outpacing overall Canadian tourism activity. Specifically, the Indigenous tourism sector’s GDP rose 23.2% between 2014 and 2017, reaching $1.7 billion.20

Lastly, Indigenous tourism businesses cite access to financing as well as marketing support and training as some of the main barriers to growth.21

Given its proximity and long shared border, the U.S. is by far the biggest source of Canada’s tourism visitors: in 2018, about two-thirds of all foreign visitors were Americans, 57% of whom arrived by automobile.22 The U.S. is also the most visited foreign destination by Canadians.

U.S. arrivals to Canada reached 14.44 million in 2018, up 1% over 2017 and the highest level recorded since 2004. American tourists like to take advantage of their long weekends for travel, with Memorial Day (the last Monday in May), Independence Day (4 July) and Labour Day (the first Monday in September) contributing to the largest weekend spikes in road arrivals in 2018.23

Americans spend around $700 per trip to Canada, staying an average of five nights. In 2018, they preferred mainly nature-based activities, including natural attractions, hiking or walking in nature, and viewing wildlife.24

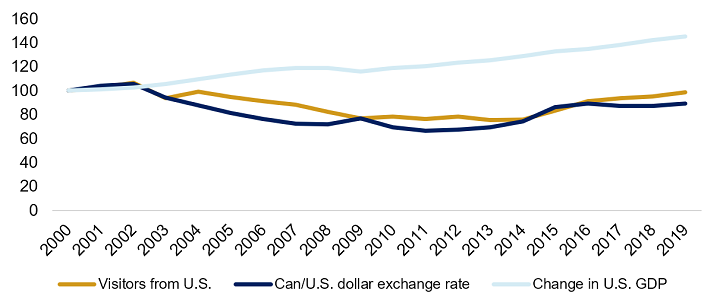

As shown in Figure 2, analysis of various factors over a 20-year period shows that the number of Americans travelling to Canada relates more to the Canadian/U.S. dollar exchange rate than to changes in the U.S. GDP.

Figure 2 – Index Comparing the Number of U.S. Visits to Canada, the Canadian/U.S. Dollar Exchange Rate and the Change in the U.S. Gross Domestic Product (GDP), 2000–2019 (2000 = 100)

Source: Figure prepared by the Library of Parliament using data obtained from Statistics Canada, “Chart 1: Tourists to Canada from abroad, annual,” The Daily, 20 February 2020; Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, “Canadian Dollars to U.S. Dollar Spot Exchange Rate,” FRED, Database, accessed 20 August 2021; and World Bank, “GDP (constant 2010 US$) – United States,” Database, accessed 20 August 2021.

According to the World Economic Forum’s Travel & Tourism Competitiveness Report 2019, Canada ranked ninth out of 140 countries studied, down from eighth place in 2013.25 Canada was ranked first in several sub-categories, such as safety and security, environmental sustainability and air transport infrastructure.

In contrast, Canada was found to be deficient in several areas, such as price competitiveness and international openness (e.g., visa requirements, air service agreements).

A 2018 report further indicated the following challenges facing the Canadian tourism sector:

These assessments suggest that even though Canada is doing well in certain areas, other jurisdictions may be greatly improving their ability to attract international tourism. Changing trends in consumer preferences may also play a role in determining which destinations may be more popular than others at any particular time.

Destination Canada is a federal Crown corporation responsible for national tourism marketing and is governed by the Canadian Tourism Commission Act. It targets the following markets “where Canada’s tourism brand leads and yields the highest return on investment”: Australia, Canada, China, France, Germany, Japan, Mexico, the U.K. and the U.S.27

In 2019, the federal government announced its new tourism strategy entitled Creating Middle Class Jobs: A Federal Tourism Growth Strategy. It is based on the following three pillars:

Part of the focus on improving tourism has been improving accessibility. To that end, in 2018, the Government of Canada introduced Bill C-81, the Accessible Canada Act, which “aims to achieve a barrier-free Canada through the proactive identification, removal, and prevention of barriers to accessibility in all areas under federal jurisdiction, including transportation services such as air and rail.”29 The bill received Royal Assent in 2019.

In 2008–2009, the federal government invested over $500 million in the tourism industry to develop facilities and events, and to promote tourism. This is in addition to investments in other areas that affect tourism, such as improvements for Parks Canada and border services.30 In 2013, funding of $42 million was allocated to improve visa services,31 an area where Canada has been found to be deficient.

Since 2016, the regional development agencies have allocated over $196 million to tourism businesses, and the Business Development Bank of Canada has provided more than $1.4 billion in financing. Export Development Canada assists Canadian tourism businesses that aim to expand into global markets.32 Budget 2017 provided Destination Canada with permanent funding of $95.5 million per year for tourism-related work, up from $58 million.33

Budget 2019 announced that starting in 2019–2020, $58.5 million over two years would go towards the creation of a Canadian Experiences Fund. The Fund supports “Canadian businesses and organizations seeking to create, improve or expand tourism-related infrastructure—such as accommodations or local attractions—or new tourism products or experiences.” These investments would focus on tourism in rural and remote communities, Indigenous tourism, winter tourism, inclusiveness (especially for the LGBTQ2 communities) and farm-to-table/culinary tourism.34

Additionally, Budget 2019 included $5 million to Destination Canada for a “tourism marketing campaign that will help Canadians to discover lesser-known areas, hidden national gems and new experiences across the country.”35

Budget 2019 also included the establishment of the Economic Strategy Table dedicated to tourism, which will bring together “government and industry leaders to identify economic opportunities and help guide the Government in its efforts to provide relevant and effective programs for Canada’s innovators.”36

Announced in Budget 2021, the Tourism Relief Fund is a $500 million national program that is part of a $1 billion package to support the Canadian tourism sector.37 Its goal is to position Canada as a destination of choice when domestic and international travel is once again deemed safe (i.e., post-pandemic) by:

Initiatives under this fund will help tourism businesses and organizations adapt their operations to meet public health requirements; improve their products and services; and position themselves for post-pandemic economic recovery.39

Part of this funding includes Destination Canada’s $2-million investment along with $950,000 of in-kind support to the Indigenous Tourism Association of Canada to “support the recovery of Indigenous tourism businesses.”40

Several federal government institutions also play key roles in shaping the outcome of Canada’s tourism economy. For example, the federal government is responsible for the following:

The National Capital Commission and Parks Canada also help ensure that iconic Canadian places are protected and preserved for current and future visitors to enjoy. As well, provincial and territorial governments help develop and promote tourism in Canada.

The Canadian tourism industry was greatly affected by the global COVID-19 pandemic. However, if international borders continue to reopen and if the industry continues its steady overall growth of the recent years prior to the pandemic, tourism will again contribute to Canada’s economic well-being. And although the U.S. continues to be Canada’s biggest tourism trading partner, stakeholders might continue their efforts of focusing on more growth-oriented, lucrative emerging markets to better diversify tourism interests and help Canada fulfil its tourism potential.

© Library of Parliament