Governments dominated the space age that emerged during the Cold War, primarily those of the United States (U.S.) and the Soviet Union. They largely treated the domain with military restraint given both the fragility of the space environment and the importance of satellites for reconnaissance and early warning of any long-range nuclear missiles.

However, the role of satellites evolved to enable conventional military operations, as was shown with U.S. military action in the 1991 Gulf War and in other operations thereafter. Space assets, therefore, came to be seen not only as a source of operational military advantage but also as a potential vulnerability. Other shifts that have taken place in recent decades include the growing number of states with capabilities and interests in space. There has also been a significant expansion of private-sector activity. Technology continues to improve and endeavours that had been prohibitively expensive are now within reach.

Over time, the number of objects and the amount of debris in orbit around Earth have increased exponentially. So has the risk of accidents, misinterpretation of intent or escalatory actions. Amid what is considered an increasingly congested, contested and competitive environment, states have struggled to build on agreements reached during the Cold War that kept space free from conflict. A diplomatic process has been initiated at the United Nations that is seeking some form of understanding in relation to responsible behaviour in space.

As is the case with its allies, space-based capabilities and space-enabled systems are key contributors to Canada’s national security and defence, and essential to its prosperity. That reliance, amplified by Canada’s vast geography, makes space a strategic concern for Canada, which informs activity in multiple domains. Canada is involved in diplomatic efforts to keep space cooperative, which ultimately involves identifying measures that could dampen strategic competition in space. At the same time, Canada’s defence posture recognizes that some states are developing capabilities that could limit access to, and the use of, the space domain.

This HillStudy explores why space is a strategic concern and how it can affect stability between and among states. It begins with an overview of the space age that emerged during the Cold War, followed by an examination of the shifts in strategic perceptions that occurred in the 1990s and 2000s. In addition to discussing the trends of crowding and competition, the paper describes how the space domain has become more contested, including through the pursuit of what are known as “counterspace” capabilities (i.e., things that can interfere with, damage or destroy space objects, the platforms on which they rely and the connection between the two). It then examines the legal framework and certain diplomatic initiatives relevant to space security and stability, and the complexities they involve. The final section of this HillStudy is focused on Canada’s international and defence policy in relation to space.

Space is a domain in which assets are both highly valuable and vulnerable. The behaviour of one actor in space, whether accidental or deliberate, can have a considerable impact on the interests of another, or even all others. That impact could be immediate or persist as a hazard for years.

The overview that follows shows that, while space is not a new strategic domain, the dynamics informing it appear to be shifting and becoming less predictable.

The space age began in 1957 with the Soviet Union’s launch of the first artificial satellite, Sputnik. Despite the object itself having little inherent military value, the demonstration of the new capability had a psychological and political impact on the United States (U.S.), which launched its first satellite the following year. With the Soviet Union’s successful use of a rocket to place a satellite in orbit around Earth, building on its test of the world’s first intercontinental ballistic missile two months earlier in 1957, distance – and the sense of security that came with it – essentially collapsed.

Being in orbit, beyond national airspace, satellites not only had freedom of overflight but also were able to cover more ground than aerial reconnaissance and had image resolution that improved over time. Although the information they collected could be used to establish targets, it appears that satellite reconnaissance of strategic capabilities had an overall stabilizing effect during an era in which surprise attacks and nuclear arms imbalances were feared.1 By providing a means of verification, satellites also contributed to the realization of nuclear arms control agreements between the Cold War superpowers.2

One scholar has observed that, in comparison to the significant expansion of U.S. and Soviet nuclear warheads from the early 1960s through to the mid-1980s, there was “a sharp decline in deployed weapons” in space [emphasis in the original]. Instead, competition was channelled

mainly into civilian and military support (and later force enhancement) realms, with devoted weapons research taking place on the margins, but resulting in little testing and almost no deployments.3

The fragility of the space environment provides one explanation for this restraint.4 Another focuses on the connection between satellites and nuclear deterrence. The disabling or destruction of early warning satellites and the communications functions associated with nuclear plans was considered high risk because it could have signalled the first stage of a nuclear war.5

The 1991 Gulf War established the importance of satellites in modern conventional military operations.6 An early version of the Global Positioning System (GPS) was one of the factors that allowed U.S.-led forces to achieve a quick victory, with minimal casualties on their side, against Iraqi forces that were heavily equipped but had less advanced weaponry and defensive systems.7 Space assets supported tasks that included acquiring targets, guiding some munitions, navigating and coordinating manoeuvres, and clearing mines.8

Nevertheless, the integration of space assets into terrestrial military operations has had strategic consequences.9 Essentially, the same space systems that provided the United States with battlefield advantages also came to be seen as “multiple vulnerable single points of failure,” which adversaries could target during conflict.10 In early 2001, a U.S. commission highlighted the country’s “relative dependence” on space and warned that the United States was “an attractive candidate for a ‘Space Pearl Harbor.’” 11

From the perspective of some observers, 1991 – a year that began with the Gulf War and ended with the Soviet Union’s dissolution – marked the beginning of a “second space age,” one that is “more diverse, disruptive, disordered, and dangerous” than what took place between 1957 and 1990.12 Space is no longer dominated by two superpowers whose relations came to be informed by relatively stable notions of deterrence and controlled escalation.13 Satellites continue to provide early warning and reconnaissance of strategic capabilities; however, they can also now be used to enable the projection of conventional military power over distances or as part of a military campaign to deny regional access to an adversary.

Furthermore, in the contemporary space age, private-sector companies are increasingly involved and, in many technological respects, are playing a leading role, including through the development of reusable launch vehicles and the miniaturization and proliferation of satellites. Journalists, researchers and others can now more readily acquire imagery from commercial satellites, which can influence policy debates when the information collected pertains to military activity and state behaviour.14

In 2011, a U.S. intelligence assessment determined that space had become increasingly “congested, contested, and competitive,” 15 phrasing that was repeated in Canada’s 2017 defence policy.16 While these concepts have been defined differently by various governments and observers, with some questioning the utility of the phrase altogether,17 they can be used to examine trends.

The congested nature of space refers to the exponential increase in the number of human-made objects orbiting Earth. There were 5,465 operational satellites in orbit as of 1 May 2022, an increase of more than 1,500 from the year before.18 While the number of states with interests in space has grown, U.S. actors – governmental and military, but mostly commercial – continue to own or operate more than half of the satellites in orbit.19 One reason for the increase in overall numbers is that the costs associated with satellites have declined significantly since their advent.20

Space appears set to become only more crowded and driven by private-sector innovation. The U.S. company SpaceX has plans to place as many as 30,000 additional satellites into orbit as part of what is known as a “mega‑constellation.” 21 Other companies are pursuing their own constellations, including Telesat, a Canadian-based company that in November 2021 applied to launch 1,373 communications satellites.22

In addition to the growing number of operational satellites, several thousand obsolete satellites continue to orbit Earth. In all, there are “approximately 23,000 pieces of debris larger than a softball orbiting the Earth,” and many more debris pieces of smaller sizes.23 Due to the high speeds at which objects orbit Earth, debris with a mass of less than one kilogram can hit a satellite with the same force as a truck speeding down a highway.24 In general, the more objects there are in orbit, the greater is the danger. For example, in 2009, an inactive Russian military communications satellite and an active U.S. satellite used for commercial communications accidentally collided at a speed of 11.7 kilometres per second, destroying both and generating more than 2,300 fragments of trackable debris.25

As space becomes more congested, the concern is that a collision could produce thousands of pieces of debris, potentially causing further collisions, which could trigger a chain reaction. In the worst-case scenario, entire segments of low Earth orbit could become unusable to both military and civilian operators.26

Some capabilities that could be used to threaten satellites have existed for decades, while new technologies and techniques are also reportedly under development.

To date, no country has deliberately destroyed a satellite belonging to another country. The last significant destructive test during the Cold War was carried out by the United States against one of its own satellites in 1985 using an air-launched missile. Following a pause in such activities, in 2007, China used the kinetic energy generated by a ground-to-space missile – known as a “direct ascent” anti-satellite (ASAT) capability – to destroy an aging weather satellite.27 Due to the estimated altitude at which the operation was conducted, many pieces of the debris remain in orbit.28 It is believed to have created “the largest debris cloud ever generated by a single event in orbit.” 29 In 2008, the United States modified the software of a missile interceptor, which it fired from an Aegis naval cruiser, to destroy one of its reconnaissance satellites that was in a degrading orbit and carrying toxic fuel.30 The timing and purpose of, and relationship between, these two events have been the subject of debate.31 In 2019, India used a ballistic missile defence interceptor to destroy one of its satellites in low Earth orbit.32

None of Russia’s suspected tests of a direct ascent ASAT system were known to have hit an object until 15 November 2021, when Russia used a missile to destroy one of its inactive satellites.33 The U.S. Department of State characterized this action as “reckless” and “irresponsible” because it had generated more than 1,500 pieces of trackable orbital debris.34 The test was also condemned by the North Atlantic Council and the European Union, while Japan, Australia and South Korea made their concerns known.35 Moreover, the U.S. civilian space agency, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), indicated that personnel aboard the International Space Station had to undertake “emergency procedures for safety” as the station passed “through or near the vicinity of the debris cloud.” 36 Russia’s foreign ministry challenged these statements.37

The most well-known – and demonstrated – ASAT capability is a missile launched from the ground, sea or air, as described above.38 Other physical threats to satellites could include an explosion, crash or rendezvous operation initiated by one object near to or against another in space. Such an operation could also involve the release of a projectile from one satellite toward another.39 The ground stations through which satellites are controlled and data are transmitted could also be attacked.40

Some states also appear to be developing capabilities that could be used to interfere with satellites or the information being exchanged between satellites and ground stations. Such interference would have the advantages of not creating a debris field in space and of being harder to attribute to the attacker. It is believed that a satellite could be temporarily disabled or permanently damaged with a laser or microwave weapon. Alternatively, an operation could be designed to jam communications between a satellite and a receiver, spoof a receiver or the satellite linked to it (i.e., introduce a fake signal or command), or intercept or corrupt data through cyber means.41

Depending on the type and severity of an attack and the sensitivity of the target, threats can be understood as being either strategic or tactical in nature.

In response to the various emerging threats, the U.S. Vice Chief of Space Operations told a Canadian audience in November 2021 that the priority of the U.S. Space Force is developing new designs, systems and architecture that are less vulnerable.42

Competition in space refers to the growing number of actors that are launching and operating satellites and other space infrastructure, including positioning and timing services that rival GPS. While the United States and the Soviet Union were responsible for some 93% of the satellites launched into orbit before the 1990s, the United States and Russia were responsible for 57% of the satellites launched between 1991 and 2016.43

Competition is not, however, the only trend that has been observed.44 A partnership of civilian space agencies from Canada, Europe, Japan, Russia and the United States has enabled the operation of the International Space Station since its launch in 1998. Interdependence is inherent to the research station’s design. For example, the Russian segment and Russian cargo spacecraft provide propulsion, including station reboost and altitude control, while the U.S. solar arrays transfer power to the Russian segment.45 Even amid the significant geopolitical tensions that have been generated by Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022, NASA and Roscosmos, the Russian space agency, were able to reach an agreement in July 2022 to send integrated flights of crew members to the research station.46 However, subsequently, a Russian official announced the country’s intention to withdraw from the research station after 2024.47 Nevertheless, no official notification has been provided.48 NASA wants to continue using the research station through 2030, at which point it aims to transition to commercial platforms in low Earth orbit.49

In 2003, China became the third country “to achieve independent human spaceflight,” 50 and has been constructing its own space station, which will be completed in late 2022.51 Arrangements are also being pursued in relation to space exploration beyond Earth’s orbit.52 China and Russia have announced agreements on Moon exploration.53 Canada is one of the signatories to the U.S.-led Artemis Accords, a political commitment concerning the safe and sustainable exploration and use of outer space.54 Canada is also contributing to the U.S.-led initiative to establish a space station – or “gateway” – in lunar orbit.55

One observer has argued that the contemporary space race is not focused on a particular destination or accomplishment. Rather, it is a race “to see who can build the broadest and strongest international coalition in space.” 56

Diplomacy in relation to space security and stability is complicated by differing state interests and perceptions, as well as by complexities related to definitions and concepts. Objects and activities in space are not easily separated into non-military and military – or peaceful and weaponized – categories. Many are dual use or could be used with differing intent. An object that could be used to service a satellite could also be used to interfere with or damage one. That situation contrasts with the singular nature of a nuclear warhead or chemical nerve agent. Nor are “space weapons” confined to space; as noted previously, objects in space can be threatened both within space and from Earth. Even when a capability is designed for a military purpose, it could be used in more than one way. For example, a system that is designed to intercept an incoming missile could also be reconfigured to destroy an object in space.

Space has been on the diplomatic agenda since the late 1950s. Diplomacy allowed the Cold War superpowers to preserve their use of space for activities – including military reconnaissance – that were perceived as being more valuable than the weaponized contestation of space.

The first arms control agreement of the Cold War – the 1963 Partial Test Ban Treaty – extended U.S.–Soviet restraint to space. The treaty prohibits nuclear weapon test explosions and any other nuclear explosions in the atmosphere, under water and in outer space.57

Broader discussions at the United Nations (UN) culminated in the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, the cornerstone of space governance. Among other provisions, the treaty specifies that outer space – including the Moon and other celestial bodies – is to remain free for exploration and use by all states and is not subject to national appropriation. Furthermore, the treaty prohibits the placement in orbit around Earth of any objects carrying nuclear weapons or any other weapons of mass destruction, as well as the installation of such weapons on celestial bodies or their stationing in outer space in any other manner. The Moon and other celestial bodies are reserved for peaceful purposes. States parties are to conduct their activities in outer space “with due regard to the corresponding interests of all other” states parties. They also bear international responsibility for national activities that are carried out in space by governmental agencies and non-governmental entities. In general, the treaty requires states parties to operate in accordance with international law, including the Charter of the United Nations.58

Other treaties adopted in the late 1960s and 1970s address the rescue and return of astronauts, liability for damage caused by space objects and the registration of objects launched into outer space.59 None of these instruments are designed explicitly to restrict non-nuclear forms of space weapons or their buildup.

Certain states have focused on what they perceive to be gaps and ambiguities in the legal framework governing space security. Others see greater opportunities in the development of shared norms and confidence-building measures. All negotiating tracks are affected by geopolitics and by technological advancements.

Resolutions on the prevention of an arms race in outer space have been adopted in the annual sessions of the UN General Assembly.61 Such documents express the political recommendations of that body, but they are not legally binding. In 2008, Russia and China put forward a draft treaty that would oblige states parties to refrain from placing any weapons in outer space and from resorting to the threat or use of force against the outer space objects of other states parties.62 The proposed treaty, which was revised in 2014, was submitted through the UN Conference on Disarmament, a consensus body that has, for various reasons, “not been able to agree on a sustainable program of work for over 20 years.” 63

Apart from the challenges involved in defining a “weapon in outer space” that does not unduly constrain civil or commercial activities, the United States has expressed concern that the draft treaty would not cover ground-to-space weapons and would not contain verification measures, which would only be negotiated afterward through an additional protocol.64 The United States has focused on voluntary measures, which it argues can be built upon.65 In April 2022, the United States committed “not to conduct destructive, direct-ascent (ASAT) missile testing,” and is seeking to establish this restraint as a norm.66 The European Union does not exclude “the possibility of a legally binding instrument in the future,” but it believes that “voluntary measures constitute a pragmatic way forward at the moment, starting with norms, rules and principles of responsible behaviours, through an incremental and inclusive process.” 67

Momentum has been building to advance a common understanding of such responsible behaviours through the work of the UN General Assembly. In December 2021, 150 states68 voted in favour of a resolution that created an open-ended working group tasked, among other things, with making recommendations

on possible norms, rules and principles of responsible behaviours relating to threats by States to space systems, including, as appropriate, how they would contribute to the negotiation of legally binding instruments, including on the prevention of an arms race in outer space.69

While the significance of this consensus-based working group will ultimately be determined by the level of state engagement it elicits, and any resulting outcome, it has been noted that the resolution supports “a shift in approach to consider and value behaviours – instead of technological hardware and capabilities – as the basis for international norm-setting.” 70

Over the years, observers have made various proposals that they believe could reinforce or expand guardrails around state competition in space.71 Canadian academics, civil society organizations, former officials and foreign ministers are among the signatories to a letter urging the UN General Assembly to pursue a treaty that would ban kinetic anti-satellite tests (i.e., tests involving some form of a physical strike).72

In addition to the procedural and technical complexities it involves, the diplomacy of space security is entwined with strategic considerations. Whereas, for example, China and Russia have drawn attention to the United States’ establishment of a Space Force and declaration that space constitutes a warfighting domain,73 the United States sees China and Russia promoting the non-weaponization of space in the diplomatic realm while continuing to pursue counterspace weapons outside of it.74

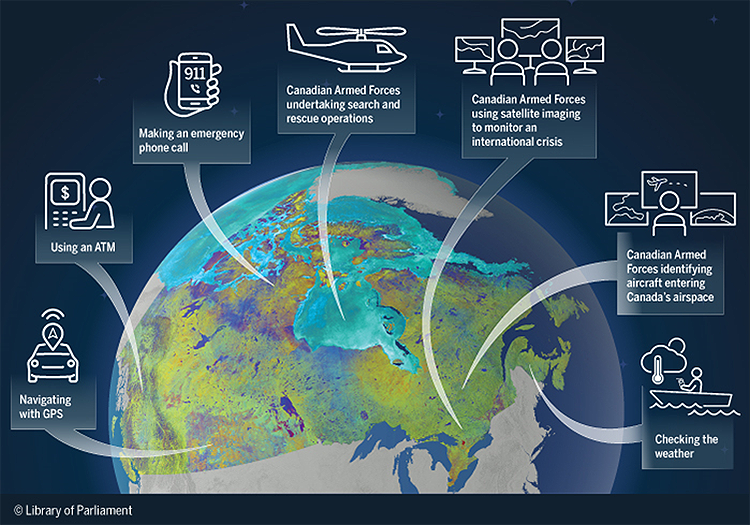

Many aspects of Canadian life depend on space. Financial transactions, telecommunications, weather forecasting and navigation using GPS are all connected to space infrastructure.75 So are government functions that must reach and cover the country’s vast territory, including through environmental monitoring, disaster response, and search and rescue. Space infrastructure helps to maintain the connections between Northern and remote communities and the rest of the country.76 For example, the Government of Canada’s announcement of an investment of more than $1.4 billion in a commercial satellite project indicated that satellites are the “only economical way” to provide high-speed Internet access to many rural and remote communities.77 For these reasons, the Government of Canada has recognized the space sector, which contributed $2.5 billion to the country’s gross domestic product in 2019, as “a strategic national asset.” 78 Figure 1 depicts some of the ways Canadians and the Government of Canada rely on space.

Figure 1 - The Importance of Space to Canada

Source: Figure prepared by the Library of Parliament using an image obtained from Government of Canada, Canada from space, RADARSAT-2 Data and products © MDA Geospatial Services Inc., 2014; and data obtained from Government of Canada, 10 ways that satellites helped you today.

With the launch of the Alouette from a U.S. military base in 1962, Canada became the third country to design and build a satellite.79 Today, and in addition to its own capabilities, Canada relies on the satellites of foreign governments and the private sector. For example, the 31 GPS satellites used for navigation in Canada are owned and operated by the U.S. Department of Defense. A September 2020 Government of Canada report acknowledged that there are “no clear options to best support private and public sector delivery of critical services in the event of disruptions” to the GPS network.80 Canada does not have its own space launch capability; consequently, its satellites must be sent to space from facilities in other countries.81

Canadian space activities depend on cooperation: between Canada and other countries; between and among Government of Canada entities; and among Canadian governments and communities, private companies and academic institutions. One example of cooperation was the June 2019 launch of Earth observation satellites to form part of the RADARSAT Constellation Mission (RCM). In comparison to the preceding generation of satellite, RADARSAT 2, the three RCM satellites provide an enhanced capability, including the capacity to “cover areas in the Arctic up to four times a day.” 82 The RCM was funded by the Government of Canada through the Canadian Space Agency and constructed in Quebec by MDA Ltd., with parts made by another private corporation in Manitoba. The satellites were then driven to California, where they were launched from a U.S. Air Force Base aboard a rocket owned and operated by SpaceX.

The RCM project took 15 years between approval and launch.83 It now provides 250,000 images per year to 12 Canadian federal departments and agencies.84 In a May 2021 interview, the Director General for Space at the Royal Canadian Air Force warned that the RCM was “oversubscribed,” which can create difficulties in managing the competing needs of entities that rely on the RCM for satellite images.85

According to Canada’s 2017 defence policy, “space capabilities are critical to national security, sovereignty and defence.” 86 The policy also conveys that, while Canada will work to promote “the military and civilian norms of responsible behaviour in space required to ensure the peaceful use of outer space,” the Canadian Armed Forces will prepare for the possibility of attacks by other states against space systems.87 According to one observer, the range of counterspace threats that exist “toss out the notion that space is a sanctuary for Canadian defence assets.” 88 On 22 July 2022, the Canadian Armed Forces established the 3 Canadian Space Division within the Royal Canadian Air Force. This new division is intended to “streamline, focus and improve how space-based capabilities support critical [Canadian Armed Forces] requirements.” 89

During its overseas military operations in the 1990s, including in the former Yugoslavia and in Somalia, Canada did not have reliable, secure satellite communications connecting deployed units with commanders in Ottawa. In the context of Canada’s mission in Afghanistan in the 2000s, and to address this gap, Canada used – and made financial contributions to – secure U.S. satellite communications systems.90

The use of other countries’ satellites – primarily those of the United States – can be seen as both an asset and a vulnerability for the Canadian military. Canada gains access to a much wider range of satellites than it could field on its own but without necessarily meeting all of Canada’s distinct defence needs. For example, one observer has noted that some of the U.S. communications satellites on which the Canadian military relies do not transmit at high latitudes, which would hinder military communication in the Arctic.91

Canada’s first dedicated military satellite, Sapphire, was launched in 2013. It provides space situational awareness (i.e., the ability to monitor objects in space) and contributes to the U.S. Space Surveillance Network.92 However, some satellites have a limited lifespan before they become obsolete; the expected lifespan of Sapphire, for example, extends to 2024.93

Recognizing that Canada has “niche” space capabilities that both complement and contribute to the capabilities provided by the United States, commentators have made various proposals regarding how Canada should prioritize its investments in security-relevant space systems.94 The 2018 Defence Investment Plan allocates funding for new military satellite systems, with a focus on systems that will provide satellite communications, including for classified information.95

Canada’s two principal defence alliances – the North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) – rely on satellites to accomplish missions.

NORAD uses a network of satellites, radars and fighter jets to “detect, intercept and, if necessary, engage” airborne threats to Canada and the United States.96 On 14 August 2021, the two countries issued a joint statement outlining a shared commitment to modernize NORAD “over the coming years,” including through investments in “a network of Canadian and U.S. sensors from the sea floor to outer space.” 97 In June 2022, Canada’s Minister of National Defence announced a multi-billion-dollar plan for investment in NORAD modernization, part of which will be used to strengthen the Canadian Armed Forces’ space-based surveillance capabilities and to enhance satellite communications in the Arctic.98

Regarding Canada’s transatlantic allies, in December 2019, NATO leaders declared space an “operational domain,” 99 and in June 2021, they declared that an attack against the space assets of NATO members could lead to a collective military response against the aggressor under the terms of Article 5 of the NATO treaty.100 NATO officials stress that the Alliance’s aims in space are defensive in nature.101 In January 2022, NATO published its “overarching” space policy, which outlines several principles and tenets, including that space “is essential to coherent Alliance deterrence and defence.” 102 Others are that Allies “will retain jurisdiction and control over their objects in space” and that “NATO is not aiming to become an autonomous space actor.” 103 While NATO has established a space centre in Germany, the Alliance itself does not possess any satellites. The intention is for NATO members to share, on a voluntary basis, “the space data, products, services or effects that could be required for the Alliance’s operations, missions, and other activities.” 104

The Government of Canada has suggested that there is a need for “careful governance” of space given the dual-use nature of space and the many benefits derived from it.105 Moreover, the Government has welcomed the development of norms of responsible behaviour in space and was one of 37 co-sponsors of the UN resolution that established the open-ended working group on reducing space threats.106According to the statement it delivered during the working group’s first session, Canada “has called for a ban on ASATs” for 40 years.107 More specifically, Canada “supports discussions, in the context of the [UN] Conference on Disarmament, on a possible ban on testing and use of anti-satellite weapons that cause space debris.” 108

The Government of Canada views “responsible” behaviours in space as those that “increase the predictability and general transparency of operations and therefore reduce the potential for hostilities in, from, or through space.” 109 Such behaviours could include the timely exchange of information and the communication of intent. In Canada’s view, irresponsible behaviours could include actions leading to damage of the space environment through the creation of debris, interference with the command and control of a satellite, and the approach or following of a satellite in a non-cooperative manner.110 It is Canada’s belief that the development of norms of responsible behaviour “will support more security and stability in space, thereby creating momentum for more ambitious steps, including the possibility of an eventual comprehensive, verifiable and legally binding regime.” 111

Since the late 1950s, space has evolved from being a domain of specialized and extraordinary government activity to something that is embedded in daily life. Space launch has become easier and less expensive, as has the operation of satellites. While there have been efforts to establish guardrails around state conduct in space, the risk of intentional or accidental disruption to space services and capabilities exists. In this context, Canada is advocating the responsible use of outer space while also addressing the implications of space having become an increasingly congested, contested and competitive environment.

© Library of Parliament