In June 2020, in response to the evolving international security environment and questions about its relevance, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) launched the NATO 2030 initiative. The COVID‑19 pandemic, the growing prevalence of disinformation, Russia’s military activities, the rise of China, and growing threats to democracy and human rights were among the trends prompting NATO to initiate this strategic reflection. Designed to strengthen NATO and its capacity to adapt quickly to emerging security challenges, the initiative is now progressing in the context of Russia’s most recent invasion of Ukraine, which NATO has characterized as “the gravest threat to Euro‑Atlantic security in decades.”

Part of the NATO 2030 initiative is a NATO 2030 agenda comprising eight proposals aimed at reinforcing NATO in various ways, including by deepening political consultations, strengthening deterrence and defence, enhancing resilience and combatting climate change. The proposals were informed by discussions among the NATO countries, and by consultations with civil society organizations, youth groups, the private sector, and an independent reflection group comprising 10 experts appointed by NATO’s Secretary General, Jens Stoltenberg. As a founding country of NATO and active contributor to NATO’s operations, Canada has consistently stated and demonstrated its support for both the initiative and the agenda.

One of the NATO 2030 agenda’s proposals concerns the development of NATO’s next Strategic Concept, a guiding document that provides a security assessment and outlines NATO’s values and purpose. Set to be adopted by the NATO leaders at their June 2022 summit, the next Strategic Concept is expected to address current threats and challenges, as well as the re-emergence of geopolitical competition. The current security environment in Europe will also affect the next Strategic Concept, and guide NATO’s future political and military development.

Throughout its history, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, or the Alliance) has continuously adapted to the evolving international security environment and has taken actions to ensure that the NATO countries remain united behind a common strategic vision.

In June 2020, NATO launched the NATO 2030 initiative, which is aimed at generating recommendations on ways to strengthen and adapt the Alliance. As part of the initiative, at their 14 June 2021 leader’s summit (2021 summit), the NATO leaders adopted NATO 2030 – a transatlantic agenda for the future (NATO 2030 agenda). The agenda comprises eight proposals designed to strengthen NATO both militarily and politically, and to enable the Alliance to adapt to future security challenges.1 The NATO 2030 initiative is now progressing in the context of Russia’s most recent invasion of Ukraine, which the Alliance has characterized as “the gravest threat to Euro-Atlantic security in decades.”2

Canada is one of the founding countries of NATO, which has been a central pillar of the country’s international security policy since the Alliance was created more than 70 years ago. Canada continues to be committed to the Alliance’s shared values of individual liberty, democracy and the rule of law, and has participated in nearly every NATO mission.3

This paper provides information about the NATO 2030 initiative, including in relation to its launch and priorities, and about the proposals adopted at the 2021 summit. It then identifies and discusses selected proposals that are particularly important for Canada, including the update to NATO’s Strategic Concept, and the potential implications of the proposals’ implementation.

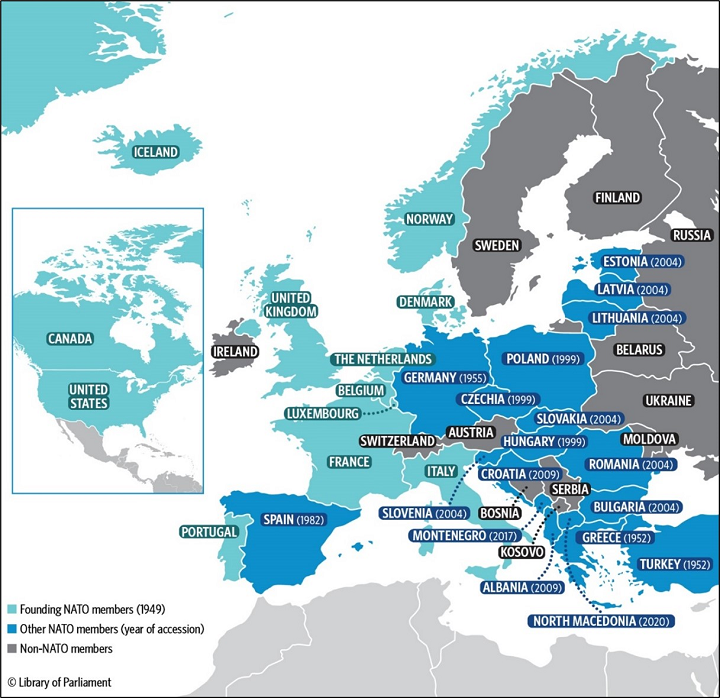

Founded by 12 countries in 1949 with the signing of the North Atlantic Treaty in Washington, D.C., NATO is a military, political and economic alliance established in response to the threat posed by the Soviet Union. At present, the 30 countries in NATO have a combined population of nearly 1 billion people and represent 50% of global gross domestic product. Figure 1 is a map of the NATO member countries which shows their year of accession and some bordering countries that are not members.

Figure 1 – Member Countries of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization and Some Non‑Member Bordering Countries, as of 20 May 2022

Note: The Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany) joined the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) in 1955. The country reunified on 3 October 1990 has retained this status.

Source: Figure prepared by the Library of Parliament using data obtained from NATO, Member countries.

According to experts, NATO’s history has been “rooted in its ability to adapt” to a changing strategic, security and political environment.4 In December 2019, as the Alliance celebrated its 70th anniversary, the NATO leaders agreed to undertake a “forward-looking reflection process … to further strengthen NATO’s political dimension” in light of the “evolving strategic environment.”5 When launching the NATO 2030 initiative in June 2020, NATO Secretary General – Jens Stoltenberg – identified terrorism, disinformation, Russia’s military activities, the rise of China and growing threats to democracy and human rights as some of the challenges in the “new normal” to which NATO must adapt.6 The NATO 2030 initiative is also being influenced by events that have occurred since its launch, such as Russia’s most recent invasion of Ukraine. On 24 March 2022, the leaders stated that the Alliance would “accelerate NATO’s transformation for a more dangerous strategic reality.”7

The NATO 2030 initiative is also a result of concerns relating to the Alliance’s cohesion and unity, tensions among the NATO countries and questions about the Alliance’s relevance.8 Among widely publicized comments questioning NATO’s purpose are then President of the United States Donald Trump’s depiction of the Alliance as “obsolete” and French President Emmanuel Macron’s characterization of NATO as “brain-dead.”9

When launching the NATO 2030 initiative, Secretary General Stoltenberg presented three priorities for NATO:10

To inform the development of the NATO 2030 initiative, Secretary General Stoltenberg consulted the NATO countries, civil society organizations, youth groups and the private sector, and appointed an independent Reflection Group comprising 10 experts from academia, public and private institutions, and governments.12 The Reflection Group’s five men and five women from 10 NATO countries included former Canadian National Security and Intelligence Advisor Greta Bossenmaier. Secretary General Stoltenberg tasked the Reflection Group with developing recommendations to strengthen NATO’s unity and political consultation mechanisms.13

In November 2020, the Reflection Group presented a report that reviewed NATO’s political role, analyzed the current security and political environments, and provided 138 recommendations. Among other findings, the Reflection Group recommended enhancing NATO’s role as a “forum for consultation on major strategic and political issues,” with a focus on the need for the NATO countries to seek consensus and build common strategies, and for NATO to upgrade its understanding of – and response to – the security challenges posed by China. As well, the report contained guidance for the development of NATO’s next Strategic Concept; the current Strategic Concept was adopted in 2010.14

Based on the proposals advocated during consultations with stakeholders and discussions among the NATO countries, at the 2021 summit, leaders agreed to the NATO 2030 Agenda. The Agenda’s eight proposals are:

The Alliance remains important to the security of Canada. As stated by the Government of Canada, the country wants NATO to remain “modern, flexible, agile and able to face current and future threats.”16 As well, Strong, Secure, Engaged: Canada’s Defence Policy (SSE) indicates that “Canada supports NATO efforts to ensure it is prepared to respond to a rapidly evolving security environment.”17 In keeping with this approach, Canada joined the other NATO countries in supporting the NATO 2030 initiative and endorsing the NATO 2030 agenda’s proposals. Following the 2021 summit, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau “reiterated Canada’s unwavering commitment to NATO and to Alliance values,” and stated that the NATO 2030 initiative “will enable NATO to meet the security challenges of today and tomorrow.”18

Through their work, Canadian parliamentarians have expressed their support for NATO’s transformation and adaptation. For example, a report by the House of Commons Standing Committee on National Defence acknowledges that, “in order to continue to be relevant today and into the future, NATO must remain vigilant in responding and adapting to the rapid changes in the international security environment.”19 Moreover, the NATO Parliamentary Assembly (NATO PA), in which Canadian parliamentarians have participated since its creation in 1955, has presented its priorities for the NATO 2030 initiative.20

By adopting the NATO 2030 Agenda, the NATO countries agreed to implement measures in relation to each of the eight proposals. To date, Canada has taken actions regarding at least the four proposals identified below.

The NATO leaders have identified deepening political consultation as one of the main ways to strengthen the Alliance’s political role, which is the overarching objective of the NATO 2030 initiative.

The Alliance’s consultation and decision-making structures, which are based on the North Atlantic Treaty, are flexible.21 Because all of NATO’s decisions are made by consensus, consultation is a key part of the Alliance’s decision-making process. In the 2021 summit communiqué, the NATO leaders pledged to “strengthen and broaden” their consultations.22 To implement this proposal, NATO has said that countries may broaden the scope of their consultations, including to encompass economic matters relating to security, such as export controls. As well, the NATO countries may increase the frequency of high-level meetings, including those of the NATO foreign ministers and such other senior officials as national security advisors.23 The Reflection Group’s November 2020 report made similar recommendations and, among other suggestions, advocated greater use of informal meetings with “freer interaction and discussion.”24

The 2021 summit communiqué also reiterated the NATO countries’ commitment to their shared values and indicated that consultations should occur “when [their] fundamental values and principles are at risk.”25 One of the NATO PA’s priorities for the NATO 2030 initiative was to reaffirm the NATO countries’ unity concerning their common values: democracy, individual liberty and the rule of law.26 Among its proposals to support this priority, the NATO PA recommended that a NATO Center for Democratic Resilience should be established to serve as a resource to monitor challenges to democracy and – upon request – provide assistance to the NATO countries.27 This recommendation is aligned with that made in the Reflection Group’s November 2020 report.28 To date, NATO has not indicated whether it will establish such a centre.

Canada has always recognized NATO’s political dimension. During negotiations for the North Atlantic Treaty, the Government of Canada successfully advocated for the inclusion of Article 2, known as the “Canada Article,” which emphasizes the NATO countries’ shared values and encourages economic cooperation among them.29 According to some observers, Canada’s advocacy concerning Article 2 demonstrates that the country views NATO not only as a military alliance, but also as a political forum in which countries are united by shared values.30 Since the signing of the North Atlantic Treaty, Canada has repeatedly reiterated its commitment to the NATO countries’ shared values and principles.

For example, in speaking to the House of Commons Standing Committee on National Defence in 2018, then Canadian ambassador to NATO Kerry Buck noted the importance of NATO’s political values and highlighted that the source of NATO’s strength is its political unity.31 In its report, the Committee recommended that Canada should “help support [the NATO countries] in upholding the shared NATO principles of protecting human rights, respecting the rule of law, promoting democracy, and protecting civilian populations.”32

Canadian observers often associate the Alliance’s political cohesion with the NATO countries’ shared values.33 For example, according to academics Christian Leuprecht, Joel Sokolsky and Jayson Derow, “without a NATO of such shared values, the Alliance would collapse and the security of Europe would be jeopardized, thus putting at risk Canada’s vital national interests.”34 Similarly, academic Andrea Charron believes that the current lack of political unity among the NATO countries makes “consensus on key threats and policy direction difficult.”35 In particular, NATO’s response to China is among the challenges that would require cohesion among the NATO countries. Other Canadian observers emphasize the Alliance’s enduring strength despite disagreements among the NATO countries and perceived challenges to their shared values. For instance, Vice-Admiral (Retired) Robert Davidson, a former Canadian military representative to NATO, feels that the diversity of views and interests among the NATO countries contributes to the Alliance’s strength.36

For the NATO leaders, strengthening the Alliance’s collective defence and deterrence posture is an important goal. Regarding this goal, the 2021 summit communiqué outlined the leaders’ commitment to maintain “an appropriate mix of nuclear, conventional and missile defence capabilities,” and to “improve the readiness of [NATO’s] forces.”37 The leaders are “plac[ing] a renewed emphasis on collective defence,” which – alongside crisis management and cooperative security – is one of NATO’s three core tasks.38 In light of Russia’s most recent invasion of Ukraine, the leaders also pledged that NATO’s deterrence and defence posture would be “significantly strengthen[ed],” including by developing a “full range of ready forces and capabilities necessary to maintain credible deterrence and defence.”39

From Canada’s perspective, citing Russia’s illegal annexation of Crimea and China’s activities in the South China Sea, SSE affirms that the “re-emergence of major power competition has reminded Canada and its allies of the importance of deterrence.”40 It adds that, while Canada contributes to efforts to deter aggression by potential adversaries, the country also benefits from the deterrent effect that NATO provides. In response to Russia’s most recent invasion of Ukraine, Canada has announced a series of measures to support Ukraine, including through NATO. For instance, the Government of Canada has announced the deployment of up to 460 additional Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) personnel in support of Operation REASSURANCE as part of NATO’s assurance and deterrence measures in Central and Eastern Europe. As well, if required by NATO, the Government has authorized the deployment of approximately 3,400 CAF personnel to the NATO Response Force.41

Among the deterrence and defence measures that were announced at the 2021 summit, the NATO leaders reaffirmed their commitment to the 2014 Defence Investment Pledge. Adopted during the 2014 summit, the Defence Investment Pledge called on all NATO countries to meet a NATO-agreed spending guideline by 2024: 2% of gross domestic product (GDP) allocated to defence, and 20% of annual defence spending allocated to major new equipment. Although Canada has not reached the 2% of GDP goal, the country is committed to gradual increases in defence spending.42 Canada also considers investments in NATO’s capabilities and contributions to operations to be essential elements of burden-sharing.43 According to NATO, Canada’s defence expenditures totalled 1.36% of GDP in 2021; the percentage in 2014 was 1.01%.44 In 2020, the Department of National Defence (DND) expected defence spending as a percentage of GDP to reach 1.48% by 2024–2025.45

At the 2021 summit, the NATO leaders also pledged to modernize the NATO Force Structure “to meet current and future defence needs.”46 The leaders endorsed a new Comprehensive Cyber Defence Policy, which will “support NATO’s three core tasks and overall deterrence and defence posture.”47 The 2021 summit communiqué reiterated previous statements that malicious cyber or hybrid activities could, in certain circumstances, lead Article 5 of the North Atlantic Treaty to be invoked; the article requires each NATO country to treat an attack against another NATO country as if it were an attack against the entire Alliance.48 Cyber threats could include disinformation campaigns, cyber attacks and, as stated for the first time in the 2021 summit communiqué, “significant malicious cumulative cyber activities.”49

At the 2021 summit, the NATO leaders agreed to adopt a broader and more coordinated approach to resilience.50 NATO defines “resilience” as “a society’s ability to resist and recover from [major] shocks and combines both civil preparedness and military capacity.”51 In Article 3 of the North Atlantic Treaty, NATO countries commit to building resilience against armed attack through “continuous and effective self-help and mutual aid.”52

Moreover, at the 2021 summit, the NATO leaders endorsed a strengthened resilience commitment as a follow-up to the “commitment to enhance resilience” made at the 2016 summit. In 2016, the leaders characterized “resilience” as “an essential basis for credible deterrence and defence and effective fulfilment of the Alliance’s core tasks.”53 The renewed focus on resilience in 2021 came not only as the COVID‑19 pandemic tested the NATO countries’ resilience, but also as the Alliance faced an evolving range of military and non-military security threats and challenges. Such resilience-related threats and challenges include: conventional, non-conventional and hybrid threats; terrorist attacks; malicious cyber activities; disinformation activities; and interference in democratic processes. Because many of these threats and challenges target civilian populations as well as critical infrastructure, resources and services, the 2021 summit commitment recognizes that strengthening NATO’s resilience requires an approach that involves governmental and non-governmental entities.54

Developing and implementing resilience plans is a national responsibility. In 2016, the NATO leaders agreed to seven baseline requirements for national resilience against which they can measure their country’s level of preparedness.55 These requirements reflect the need to maintain essential public services and to continue government operations during a crisis. Over time, NATO has updated its baseline requirements to reflect the challenges presented by communication technologies, including fifth generation – or 5G – wireless technology, as well as the impacts and implications of the COVID-19 pandemic.56

As part of the NATO 2030 agenda, the NATO leaders agreed to establish objectives to provide additional guidance concerning national resilience goals and implementation plans. This guidance would allow NATO to review and monitor national resilience efforts.57 In addition, the leaders indicated that they would designate a senior official to coordinate resilience efforts at the national level and facilitate consultations within NATO.58

Among its priorities for the NATO 2030 initiative, the NATO PA recommended that the Alliance should continue to assist the NATO countries as they build their resilience.59 In an October 2021 resolution, the NATO PA supported the inclusion of resilience in the NATO 2030 agenda and the adoption of the Strengthened Resilience Commitment. Among other recommendations, the NATO PA urged: a NATO‑conducted review of its baseline requirements; the development of early warning systems and emergency plans in cooperation with military and civilian entities; and the identification of lessons learned from the COVID‑19 pandemic regarding resilience, notably concerning the capacity of health infrastructure to respond to a crisis.60

According to the NATO 2030 agenda, NATO should ensure that it understands and adapts to the impacts of climate change on security.61 For NATO, this proposal means not only understanding the ways in which climate change may affect the security conditions in which the Alliance operates, but also addressing the climate-related impacts of its military activities.

Although NATO has recognized climate change as a security challenge for many years, the 2021 summit communiqué was the first such communiqué in which the NATO leaders described climate change as a “threat multiplier that impacts Alliance security.”62 Climate change is seen as a threat multiplier because it aggravates situations, such as poverty and natural resource scarcity, that give rise to conflicts and instability. This characterization of climate change is consistent with the NATO PA’s priorities for the NATO 2030 initiative. For example, the NATO PA’s 2020 declaration recommended that NATO should “fully recognise climate change-related risks as significant threat multipliers.”63

As part of the climate change–related proposal adopted at the 2021 summit, the NATO leaders committed to reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from the Alliance’s military activities and installations, and from the NATO countries’ military structures and facilities. The leaders also agreed to develop a GHG reduction target and to assess the feasibility of achieving net-zero emissions by 2050. As well, starting in 2022, NATO will begin to organize a “regular high-level climate and security dialogue.”64

Moreover, at the 2021 summit, the NATO leaders adopted the NATO Climate Change and Security Action Plan, which provides a framework for implementing the Climate Change and Security Agenda endorsed by the NATO foreign ministers in March 2021. Among other measures, the action plan requires NATO to conduct annual assessments of the impacts of climate change on its strategic environment, as well as on its installations, missions and operations. NATO will issue its first Climate Change and Security Progress Report at the 2022 summit.65

In Canada, DND is the federal government’s largest user of energy and generator of GHG emissions.66 SSE states that DND plans to “[r]educe [GHG] emissions by 40 percent of the 2005 levels by 2030.”67 In its November 2020 report, the NATO Reflection Group recommended the establishment of a NATO Centre of Excellence on Climate and Security.68 During the 2021 summit, Prime Minister Trudeau announced Canada’s proposal to establish and host such a centre to:

With the aim of establishing the NATO Centre of Excellence on Climate and Security in 2023, the Government of Canada, NATO and the NATO countries have initiated negotiations regarding the centre’s design.70

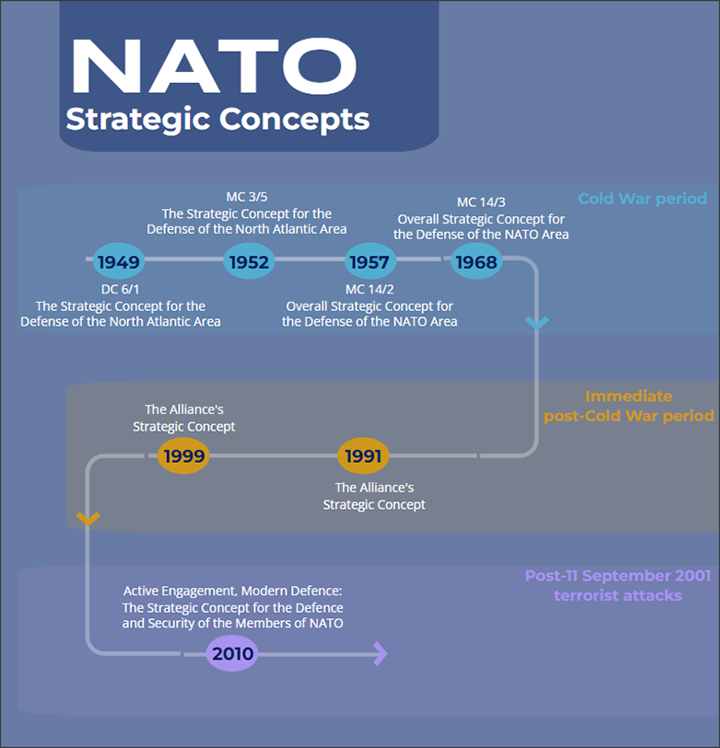

At the 2021 summit, as part of the NATO 2030 agenda and in keeping with the Reflection Group’s recommendations and vision, the NATO leaders invited Secretary General Stoltenberg to guide the process of developing the Alliance’s next Strategic Concept. As shown in Figure 2, NATO’s Strategic Concepts were updated at an irregular frequency prior to the end of the Cold War, but they are now updated approximately every 10 years.

Figure 2 – The North Atlantic Treaty Organization’s Strategic Concepts, 1949 to Present

Note: The Strategic Concepts produced during the Cold War period were classified. The 1949 Strategic Concept was approved by the Defense Committee (DC) of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), a committee of the NATO defence ministers that operated from 1949 to 1951. The 1952, 1957 and 1968 Strategic Concepts were adopted by NATO’s Military Committee (MC), which is a committee of senior military officers of the NATO countries.

Source: Figure prepared by the Library of Parliament using information obtained from NATO, Strategic Concepts.

NATO is not alone in undertaking a strategic reflection on European security. The Strategic Compass is a strategic document by the European Union (EU) which outlines the concrete objectives of the EU Common Security and Defence Policy, and was adopted in March 2022.71

For several observers, the concurrent development of these strategic documents provided NATO and the EU with an opportunity to reflect on the division of responsibilities between them.72 The Strategic Compass underlines that the EU’s approach to European security is “complementary to NATO, which remains the foundation of collective defence for its members.”73 Because Russia’s most recent invasion of Ukraine has reinforced the notion that NATO is the main military and political alliance responsible for European security and defence, some commentators believe that – in the current European security environment – the view that the EU is a security provider seems “amateurish and risky.”74 For other researchers, the war in Ukraine highlights the need for an EU defence policy that complements NATO’s next Strategic Concept.75

NATO’s next Strategic Concept will outline the Alliance’s purpose and fundamental tasks, provide an assessment of the current security environment, and identify NATO’s approach to security. As part of the process to develop this Strategic Concept, Secretary General Stoltenberg initiated consultations with the NATO countries and interested stakeholders.

NATO organized four seminars designed to gain the perspective of the NATO leaders, academics, youth groups, civil society organizations and the private sector. Co-hosted by Poland, Portugal and the United Kingdom, the first seminar – “Deterrence and Defence in the XXI century” – was held on 13 December 2021,76 while the United States Ambassador to NATO hosted the second seminar, “Future Proofing the Alliance: New and Emerging Challenges and Principles for NATO’s Future Adaptation,” on 4 February 2022.77 “Stronger Together – NATO’s Partnerships,” the third seminar, took place on 23 February 2022; it was co-hosted by Germany and the Netherlands, and was sponsored by Canada, Italy, Portugal, Spain and two of NATO’s partners: Finland and Sweden.78 Czechia hosted the final seminar, “NATO’s evolving role in global stability,” on 28 March 2022.79

The NATO countries will use the insights gained during these seminars as the next Strategic Concept is negotiated; it is expected to be endorsed by the NATO leaders at the 2022 summit.

In November 2021, during a meeting of the NATO foreign ministers, Secretary General Stoltenberg outlined five objectives to guide the development of the next Strategic Concept:

According to the Reflection Group’s November 2020 report, because the current Strategic Concept was developed prior to “the emergence of many of the current security setting’s key features, including most notably the return of confrontation with Russia and systemic rivalry with China,” it is an inadequate basis for responding to the current international security environment.81 For example, the current Strategic Concept recommends cultivating a “strategic” and “constructive” partnership with Russia and does not mention China.82

At the 2021 summit, China was referenced for the first time in a communiqué section on threats and challenges. In October 2021, Secretary General Stoltenberg explained that the 2021 summit communiqué contains NATO’s new position toward China, which is expected to be reflected in the next Strategic Concept.83 The communiqué mentioned that “China’s stated ambitions and assertive behaviour present systemic challenges,” and specifically identified the country’s:

Prior to Russia’s most recent invasion of Ukraine, the geopolitical tensions resulting from Russia’s aggressive actions in Ukraine and Georgia, as well as ongoing Russian military build-ups in the Baltic and Black seas, in the Mediterranean and in the Arctic, were already expected to influence NATO’s next Strategic Concept. Repeating language first used in the 2019 summit communiqué, the 2021 summit communiqué identified “Russia’s aggressive actions” as a “threat to Euro-Atlantic security.” Among the challenges posed by Russia, the 2021 summit communiqué listed the country’s:

Russia’s most recent invasion of Ukraine is expected to affect the content of NATO’s next Strategic Concept, including in two areas: membership in the Alliance, and partnerships and relationships with other organizations and countries, such as Russia.86 In light of the current European security environment, Finland and Sweden – which have historically pursued policies of “military nonalignment” – have applied for membership in NATO.87 In keeping with NATO’s “open door policy,” Secretary General Stoltenberg stated that Finland and Sweden “will be welcomed with open arms.”88 Moreover, NATO leaders have agreed to “accelerate NATO’s transformation for a more dangerous strategic reality,” including through the next Strategic Concept.89 Commentators argue that, while Russia’s threat to European security requires NATO’s attention in the short term, the threat must be addressed in the next Strategic Concept.90

In addition to addressing the re-emergence of geopolitical competition, the next Strategic Concept is expected to consider other ongoing and/or evolving global threats and challenges, such as cyber and hybrid threats, rapid advances in the space domain, climate change and terrorism.91

In an October 2021 resolution, the NATO PA stated that the next Strategic Concept should address terrorism, a challenge that has evolved since the NATO countries and NATO’s partners first deployed to Afghanistan. Among other recommendations, the NATO PA called on NATO to incorporate lessons learned from its operations in Afghanistan – including in relation to counterterrorism – into the next Strategic Concept.92

The 2010 Strategic Concept identified three core tasks for NATO:

Over time, including at the 2021 summit, the NATO leaders have reaffirmed the Alliance’s commitment to fulfilling those three core tasks. The Reflection Group’s November 2020 report stated that these core tasks are among the elements of the 2010 Strategic Concept that should be preserved in the next Strategic Concept.93

A number of commentators have suggested that NATO should have “resilience” as a fourth core task.94 From this perspective, the future-oriented and adaptive nature of resilience would provide a foundation for NATO’s fulfilment of its existing core tasks. However, some academics have argued that NATO should not adopt additional core tasks, but should instead refocus its approach on deterrence and defence against “systemic rivals” – China and Russia – as the Alliance’s principal core task.95 In their Shadow Strategic Concept 2022, members of The Alphen Group, a self-described “network of leading security policy experts,” suggest that, rather than being framed as a core task, resilience should be a “priority” that would reinforce the three existing core tasks.96

Other suggestions regarding NATO’s core tasks aim to address specific threats to national security, such as terrorism. The 2010 Strategic Concept identifies terrorism as a part of the security environment, but it focuses on the need for enhanced analysis by, consultations with and training of local military and law enforcement entities to combat terrorism. Since 2010, NATO has recognized that counterterrorism efforts span all of NATO’s core tasks. In the context of the evolving strategies used by terrorist networks and groups, and their use of emerging technologies, the Reflection Group’s November 2020 report recommended that counterterrorism should be explicitly integrated into NATO’s core tasks.

The NATO 2030 initiative is progressing as global challenges, such as the COVID-19 pandemic and climate change, are exacerbating existing threats. NATO’s strategic reflection is also informed by an evolving security environment, which Secretary General Stoltenberg has characterized as “more complex and contested than ever before.”97 Russia’s most recent invasion of Ukraine highlights the pressure on NATO both to adapt to a continuously changing security environment and to demonstrate its unity and ability to respond to military aggression in Europe. According to the NATO PA, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine shows the “relevance and timeliness” of the NATO PA’s priorities for NATO’s next Strategic Concept, which are to reaffirm the Alliance’s shared values and adapt NATO to the current international security environment.98

In keeping with Canada’s active membership in NATO over the past seven decades, the country has both supported and contributed to discussions about NATO’s future that are occurring as part of the NATO 2030 initiative, the NATO 2030 agenda’s eight proposals and the development of NATO’s next Strategic Concept. Moreover, there is a broad consensus that a strong NATO able to adapt quickly to a changing global security environment is in Canada’s security interests. In February 2022, Minister of National Defence Anita Anand said that “Canada’s commitment to the NATO Alliance is unwavering, and [Canada] will continue to work with [its] Allies to maintain a modern, agile and united alliance in the face of current and future challenges.”99

NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg has referred to three elements of burden-sharing, or the "three Cs'": cash, capabilities and contributions. For example, see Jens Stoltenberg, NATO Secretary General, Doorstep statement by NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg prior to the meetings of NATO Defence Ministers, 14 February 2018.

[ Return to text ]

© Library of Parliament