High-speed (or broadband) Internet has become integral to the lives of most Canadians. Broadband Internet service is all the more important in rural and remote areas, because it makes it possible to provide various essential services to the people who live in these areas, such as education and medical care, to which they often would not have access otherwise.

Even though the Government of Canada has undertaken multiple initiatives, connectivity across the country remains unequal; Canadians in urban areas have access to a wide variety of Internet services, while those living in rural and remote communities still have limited or no access to broadband service. One reason for this inequality is the extremely high cost of building broadband networks, particularly in more isolated areas. This HillStudy provides an overview of the issues with broadband Internet access in rural and remote areas of Canada and the initiatives taken in response to these issues.

High-speed (or broadband)1 Internet has become an integral part of the lives of many Canadians. Moreover, governments at all levels offer an increasing number of services online. Access to broadband Internet is even more important in rural and remote areas, because it makes various essential services, like education and medical care, available to the people who live there and who often would have no access to them otherwise.

Given that Canada’s population is unevenly distributed over a vast landscape – most Canadians live in communities along the border with the United States – connectivity across the country remains unequal. Canadians who live in urban areas have access to a wide variety of Internet services, while those living in rural and remote areas continue to have limited or no access to broadband Internet, mainly because of the extremely high cost per capita of building broadband networks. Their cost-effectiveness is highly dependent on the population density of the market. This gap in connectivity between urban and rural areas, often referred to as the “digital divide,” is a concern for policy-makers at all levels of government.

In December 2016, the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) declared that broadband Internet access is a basic telecommunication service for all Canadians, and it set the following targets for the basic service Canadians need to participate in the digital economy:

In 2019, the Government of Canada launched High-Speed Access for All: Canada’s Connectivity Strategy in which it stated that 84% of Canadian households had access to speeds of 50/10 Mbps and pledged to bring these speeds to 90% of Canadian households in 2021, 95% in 2026 and 100% in 2030.3 Data from June 2023 showed that 91.4% of Canadian households had access to a broadband Internet connection, which meets the CRTC target, but only 62% of households in rural regions had the same access. In terms of access to LTE mobile technology, 99.4% of Canadians have coverage. More specifically, 97.1% of individuals who live in rural areas have access to LTE, as do 87.2% of those who live along highways and major roads.4

A digital divide separates those who have access to broadband Internet from those who do not. There are two main types of digital divide: technical and socio‑economic. The technical digital divide refers to the accessibility or technical capacity for high‑speed connectivity. Although there may be areas in cities (or on the outskirts of cities) without broadband Internet access, the technical digital divide generally refers to the gap between urban and rural or remote areas.

The socio-economic digital divide relates to choice and barriers to access; in fact, those who have access to broadband Internet services may not subscribe to them. The barriers to access that cause this type of divide can be related to age, income, education, language, gender or other identity factors. They can also depend on digital literacy. It is important to bridge the socio-economic digital divide in order to establish a digital society that leaves no one behind. This study, however, addresses the fundamental problem of technical access to broadband service.

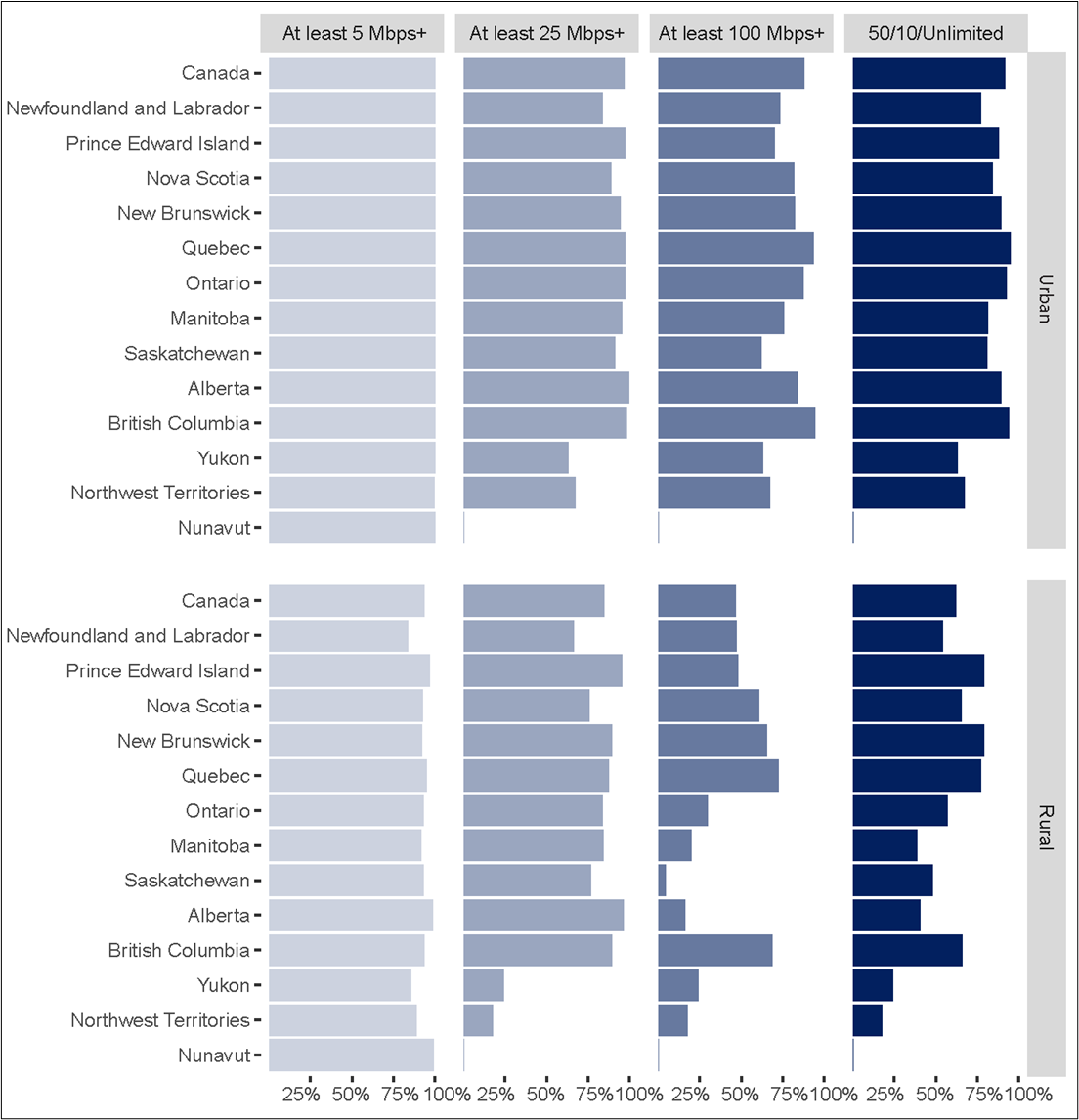

Figure 1 illustrates the broadband availability gap between urban and rural areas in Canada and the progress made in provinces and territories to meet the CRTC target of 50/10/unlimited data.

Figure 1 – Availability of Broadband Service in Urban and Rural Areas of Canada, by Province and Territory, by Download Speed and Percentage of Households, 2021

Source: Figure prepared by the Library of Parliament using data obtained from Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission, “Current trends – High-speed broadband,” Communications Market Reports.

While very little disaggregated data on broadband Internet access in Indigenous communities exist, there are often major differences between broadband Internet access in Indigenous communities (located in urban, rural and remote areas) and in non‑Indigenous communities. The Library of Parliament has prepared a HillNote on this topic.5

Canada is a vast and sparsely populated country with dramatically varying landscapes and climates. Its population density is 3.9 persons per square kilometre (persons/km2). For comparison, Table 1 provides data on population density and urbanization in selected countries.

| Country | Area (km²) | Population (millions) | Density (persons/km²) | Urbanization (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | 7,741,220 | 26.5 | 3.4 | 86.6 |

| Belgium | 30,528 | 11.9 | 389.8 | 98.2 |

| Canada | 9,984,670 | 38.5 | 3.9 | 81.9 |

| Finland | 338,145 | 5.6 | 16.6 | 85.8 |

| France | 643,801 | 68.5 | 106.4 | 81.8 |

| Hong Kong | 1,108 | 7.3 | 6,588.4 | 100 |

| Japan | 377,915 | 123.7 | 327.3 | 92 |

| Singapore | 719 | 6.0 | 8,344.9 | 100 |

| South Korea | 99,720 | 52.0 | 521.5 | 81.5 |

| United Kingdom | 243,610 | 68.1 | 279.5 | 84.6 |

| United States | 9,833,517 | 339.7 | 34.5 | 83.3 |

Source: Table prepared by the Library of Parliament using data obtained from Central Intelligence Agency, “The World Factbook ,” Database. Population data is a July 2023 estimate; urbanization data is the percentage of the total population living in urban areas, as defined by the country, in 2023. Density is calculated using data from The World Factbook.

Canada’s population distribution and geography are sometimes referenced as a reason for which Canadians receive lower-quality broadband Internet service, but pay higher prices than citizens of other developed countries. For example, Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada (ISED) explained in its introduction of the Connect to Innovate program that in rural and remote communities, “[c]hallenging geography and smaller populations present barriers to private sector investment in building, operating and maintaining infrastructure.” 6

While Canada’s population density is very low compared to other countries, this overall average can be misleading, because population density is not constant across the country, and the average represents neither the high density of urban areas nor the very low density in rural and remote areas. Comparing the North (Yukon, the Northwest Territories and Nunavut) with Canada’s five largest census metropolitan areas (CMAs) (Toronto, Montréal, Vancouver, Calgary and Ottawa–Gatineau) shows how a measure based on total population and total land area can be misleading. In 2021, the North represented 39% of Canada’s land mass and only 0.3% of its population, for a population density of 0.013 persons/km². The five largest CMAs comprised 0.3% of the country’s land mass, but 43.5% of the population, for a population density of 605.6 persons/km2.7

Moreover, ISED has, for several years now, commissioned an annual study that compares prices between wireline, wireless and Internet services in Canada and abroad. The latest study was conducted in 2022. It shows that the average price of broadband Internet service in Canada is higher than in all countries surveyed except Japan, including countries like Australia with a similar population density. Canadian prices for these services, however, are higher than or similar to Japan’s for connection speeds greater than 40 Mbps.8 Thus, although Canadian demographics explain in part the high cost and difficulty of deploying broadband Internet service in rural and remote areas, they do not fully explain the situation. Several stakeholders have often pointed to the lack of competition in telecommunications services in Canada, particularly in rural and remote regions, as another partial explanation.9

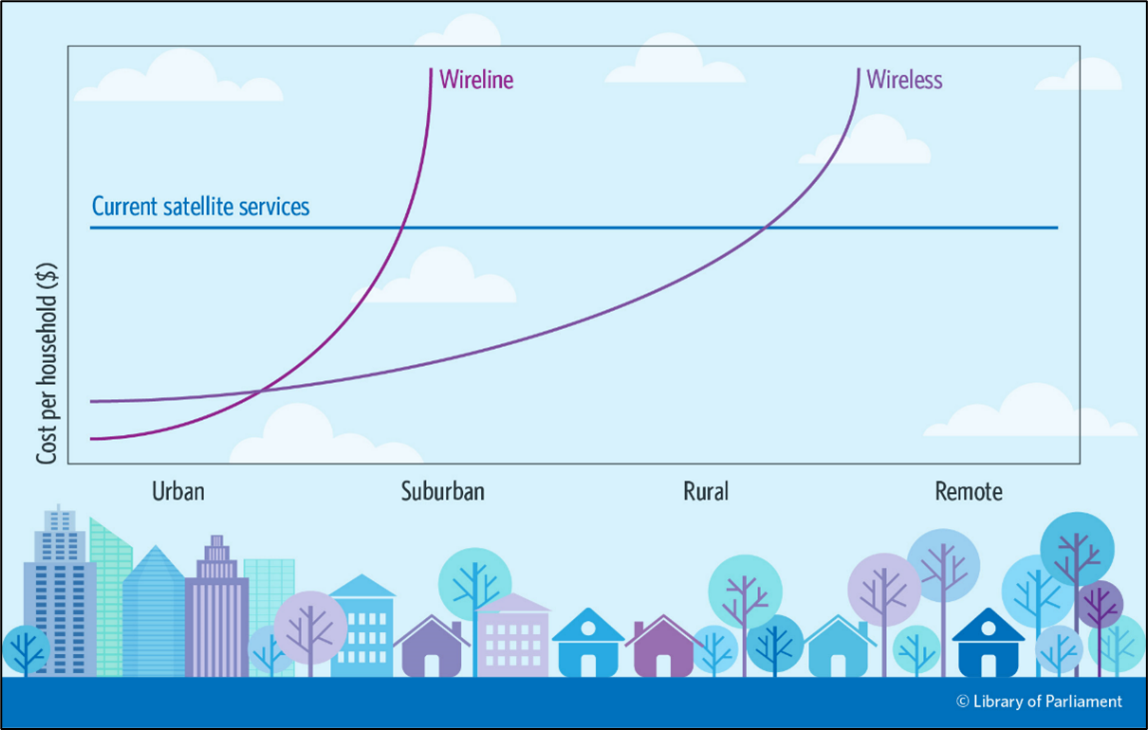

The cost-effectiveness of various broadband Internet delivery systems depends largely on the population density in the targeted regions. Figure 2 shows how declining population density leads to higher capital costs for Canadian households with wireless or wireline broadband Internet (wire or fibre). On the contrary, costs do not rise the same way for satellite services because of their vast coverage, but their technical features make them an option for sparsely populated areas only.

Figure 2 – Cost-Effectiveness of Broadband Delivery Systems by Population Density

Source: Figure prepared by the Library of Parliament using data obtained from Brightstar Canada, Nova Scotia Department of Business Last Mile Strategy ![]() (1.3 MB, 46 pages), May 2018.

(1.3 MB, 46 pages), May 2018.

In 2021, nearly one million Canadian households depended on fixed wireless and satellite technologies for their Internet connection:

Some view these technologies as a short-term connectivity solution for use while the government and industry work toward long-term solutions (for example, extending fibre optic networks to rural and remote areas).12 Others believe that wireless service will always be needed in certain remote communities.13

Given that wireless technologies are particularly important for deploying broadband Internet in rural and remote areas, it is imperative that access to radiofrequency spectrum licences be considered. To provide more information about the spectrum management process in Canada, the Library of Parliament has prepared both a HillNote and a working paper on the subject.14

ISED and the CRTC are responsible for different aspects of telecommunications services in Canada. While they have separate roles, they also work together on many levels, as they do with funding programs for broadband Internet deployment.

In recent years, the Government of Canada has introduced various programs and initiatives to improve broadband Internet coverage in Canada and meet the targets set by the CRTC. The Government of Canada reports that it has invested over $7.6 billion in connectivity since 2015.15 For example:

Moreover, as part of the Universal Broadband Fund, the Canada Infrastructure Bank (CIB) is collaborating with ISED to support the implementation of large and small broadband Internet projects proposed by Internet service providers across Canada. To achieve this, the CIB has pledged up to $3 billion, alongside contributions from ISED, in debt or equity investments.25

In 2018, the Office of the Auditor General of Canada (OAG) published a first audit report on connectivity in some rural and remote areas, in which the OAG noted Canada’s need to establish a national strategy to improve connectivity in rural and remote areas.26 In spring 2023, the OAG published a second report on this topic which found that, although connectivity in the country improved through government initiatives, the digital divide persists, particularly for Canadians living on First Nations reserves and in rural and remote areas. The OAG noted that neither ISED nor the CRTC have the data needed to get a full understanding of the quality and affordability of the Internet services available across the country.27

If we are to have a truly inclusive digital society, all Canadians must have access to broadband Internet service. Accordingly, the Canadian government has put in place a strategy with a goal of achieving the CRTC targets for broadband Internet for all Canadians by 2030. The government will then be able to take measures to bridge the socio-economic digital divide to allow all Canadians – not only those living in urban areas – to benefit fully from our 21st‑century digital society.

* This HillStudy is largely based on Sarah Lemelin-Bellerose, Dillan Theckedath and Terrence J. Thomas, Rural Broadband Deployment, Publication no. 2011-57-E, Library of Parliament, 17 July 2019.

© Library of Parliament