Gender equality means that every person, regardless of their gender identity, has the same rights, responsibilities and opportunities. While in Canada, every individual is equal and has the right to equal protection and benefit of the law, in practice, gender-based inequalities and discrimination persist and are more prevalent among certain groups.

Gains have been made in a number of areas relating to gender equality over the past few decades. For example, women represent the majority of recent post-secondary graduates, and as of January 2025, they represent more than half of senators and nearly one-third of members of Parliament.

However, inequalities remain in a number of areas. In education, women remain the minority among degree holders in the science, technology, engineering and mathematics fields. For example, in the 2021–2022 academic year, women represented 24% of post-secondary students in architecture, engineering and related technologies and 27% of students in mathematics, computer and information sciences.

The gender wage gap, or the difference in earnings between men and women, while smaller than in previous decades, persists and is particularly notable for Indigenous women, immigrant women and women with children.

Women, and particularly Indigenous women, face increased rates of certain types of violence. For example, in 2018, almost half of Indigenous women and girls over 15 years of age self-reported that they had experienced sexual assault in their lifetime. More than one-third of non-Indigenous women reported the same. Experiencing violence can affect an individual’s sense of personal safety, which can lead to feelings of discomfort or fear. Many victims of unwanted sexual behaviour while in public – for example, sexual comments or attention – change their behaviour after the incident, such as avoiding certain places and changing routines.

The federal government has implemented a number of legislative measures to improve gender equality. The Pay Equity Act aims to support progress towards pay equity by requiring employers to provide equal pay for work of equal value. Amendments to the Canada Labour Code have increased benefits for maternity leave, parental leave and compassionate care leave, as well as provided leave of absence for victims of family violence.

Further federal initiatives to support gender equality include developing the National Action Plan to End Gender-Based Violence, which aims to prevent gender based violence and supports victims and survivors; allowing individuals who do not identify as female or male to mark “X” on their travel documents; and launching the Women Entrepreneurship Strategy, which supports women entrepreneurs by providing venture capital funding and networking and mentorship opportunities.

The concept of gender equality is that every person, regardless of their gender identity, has the same rights, responsibilities and opportunities.1 Substantive gender equality is created when laws, programs and policies consider different impacts on people of different genders and do not reinforce or perpetuate inequalities or further disadvantage people based on gender.2

In Canada, every individual is “equal before and under the law and has the right to equal protection and equal benefit of the law without discrimination.”3 However, in practice, gender-based inequalities and discrimination persist and are more prevalent among certain groups.

The right not to be discriminated against on the basis of sex is a universal human right incorporated into international human rights instruments, including article 2 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights,4 The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women and its Optional Protocol, and other core human rights treaties.5

Several international, regional and national human rights instruments recognize gender equality as a human right; equality of rights for women is a basic principle of the United Nations (UN).6 One of the UN’s 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) is SDG 5, which aims to achieve gender equality.7 To achieve the SDGs, Canada has adopted a national strategy with a Canada-specific indicator framework and makes its progress reports available on a data hub.8

In Canada, the legal foundations for gender equality are enshrined in the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms (the Charter), which guarantees the right to equality before and under the law and equal protection and benefit of the law, and provides that all Charter rights are guaranteed equally to “male and female persons.”9 In addition, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity and gender expression, as well as marital and family status, are prohibited grounds for discrimination under the Canadian Human Rights Act,10 which applies to the federal government, other federal organizations, First Nations governments and federally regulated employers.

Gender inequalities are apparent in a number of contexts in Canada. Some people may face additional or intersectional discrimination and inequality due to other identity factors, such as race, disability and sexual orientation or gender identity, which can amplify or compound the inequalities they face. Some refer to this interaction of multiple forms of discrimination as “intersecting systems of oppression.”11 The following sections of this HillStudy give an overview of existing gender inequalities by issue.

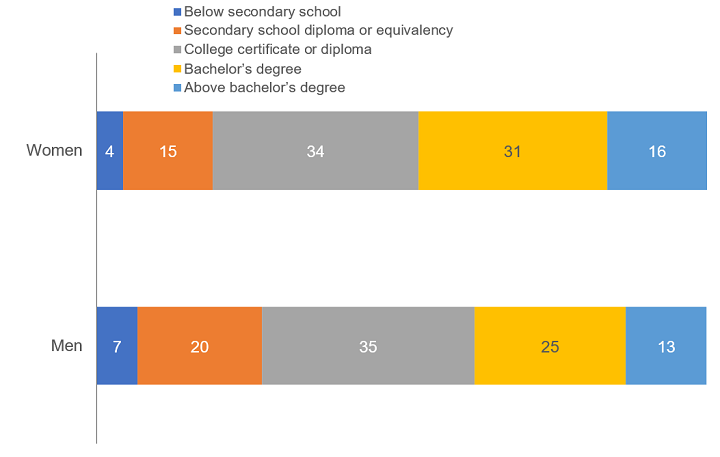

Certificate, degree and diploma completion rates vary by gender. Women in Canada represent the majority of recent post-secondary graduates in all provinces and territories and are the majority of university degree holders in most fields of study. Further, the proportion of women completing post-secondary education has increased at a rate faster than that of men in recent decades.12 In 2024, 81% of women aged 25 to 54 years had completed post-secondary education compared to 73% of men in the same age group, as shown in Figure 1. Using data from Statistics Canada’s Canadian Community Health Survey, gay or lesbian people are more likely to hold a bachelor’s degree or higher when compared to their heterosexual counterparts.13

Figure 1 – Proportion of Women and Men Aged 25 to 54 Years by Educational Attainment, 2024 (%)

Source: Figure prepared by the Library of Parliament using data obtained from Statistics Canada, “Table 14-10-0118-01: Labour force characteristics by educational degree, annual,” Database, accessed 22 January 2025.

Despite women receiving more post-secondary degrees, they remain the minority among degree holders in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) fields, occupations that are often associated with high-quality, high-paying jobs.14 In the 2021–2022 academic year, women represented 23.7% of post-secondary students in architecture, engineering and related technologies and 27% of post-secondary students in mathematics, computer and information sciences.15 Gender stereotypes, microaggressions and a lack of women role models have been identified as significant contributing factors in the underrepresentation of women and girls in STEM education fields: “[g]irls’ disadvantage is not based on cognitive ability, but in the socialisation and learning processes within which girls are raised and which shape their identity, beliefs, behaviours and choices.”16

Gender-based differences and inequalities affect the economic well-being of Canadians.17 Overall, women in Canada have a lower average personal income than men ($48,400 for women versus $66,000 for men in 2022). Women, particularly senior women, lone mothers, Indigenous women and women with disabilities are also more likely to live with lower incomes than men.18 Further, Statistics Canada found that in 2020, a higher proportion of transgender men (12.9%) and transgender women (12%) were likely to experience low income compared to cisgender men and women (8.2% and 7.9%, respectively), and non-binary people lived in poverty at more than twice the national rate (20.6%).19

Several factors may help explain the overall gender gap in economic well-being, particularly:

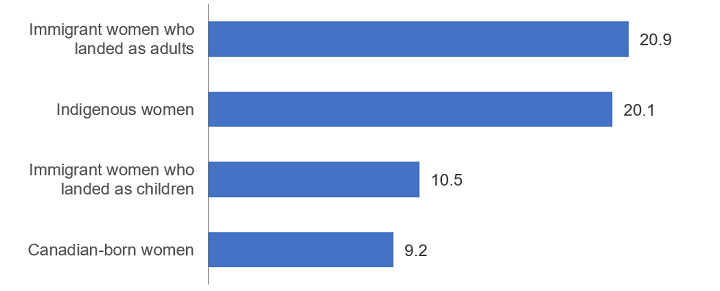

Figure 2 – Gender Wage Gap Relative to Canadian-Born Men by Group of Women, 2021 to 2022 (%)

Source: Figure prepared by the Library of Parliament using data obtained from Statistics Canada, “Intersectional Gender Wage Gap in Canada, 2007 to 2022 – Chart 1: Gap in average hourly wage relative to Canadian-born men, by group of women, 2007 to 2008 and 2021 to 2022,” The Daily, 21 September 2023.

In Canada, some demographic groups, including women, are underrepresented in electoral politics. According to Equal Voice, a Canada-based not-for-profit dedicated to equality in democratic representation, women and gender-diverse candidates represented 43% of all candidates who stood for office in the 2021 federal general election across the five parties represented in Parliament.31 According to Elections Canada data, individuals identifying as gender minorities accounted for less than 1% of candidates in the 2021 federal election.32 Further, racialized women accounted for 6% of candidates and Indigenous women accounted for 2% of candidates during the 2019 federal elections.33

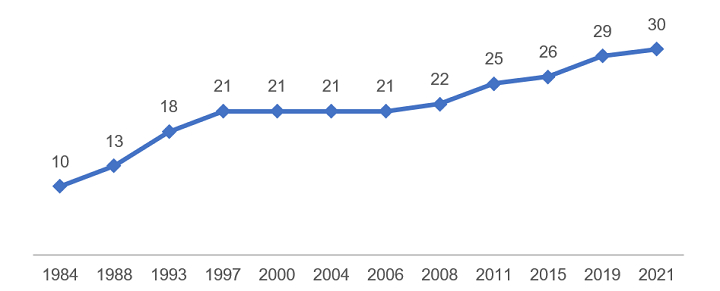

As of January 2025, women represented 31% of members of Parliament and 54% of senators.34 As shown in Figure 3, women’s representation in the House of Commons has increased over time, tripling between the 1984 and 2021 federal general elections. The first openly Two-Spirit candidate was elected to the House of Commons in 2021.35 In 2015, gender parity was achieved among federal Cabinet ministers for the first time, a practice that was maintained following the 2019 and 2021 federal elections.36

In terms of Indigenous women’s political representation at the band level, in 2019, Statistics Canada found that one in five First Nations leaders was a woman, and that more than a quarter of First Nations council members were women.37

Figure 3 – Proportion of Women Among Elected Candidates to the House of Commons in Federal General Elections Between 1984 and 2021 (%)

Source: Figure prepared by the Library of Parliament using data obtained from Library of Parliament, “Elections and Candidates,” Parlinfo, Database, accessed 14 January 2025.

Various barriers contribute to the underrepresentation of women in politics, including the following:

Women are also much less likely to run in “party stronghold” ridings than men. In the 2019 federal elections, white women ran in stronghold ridings half as often when compared to white men. Further, racialized men and racialized women each ran only one-third as often as white men in such ridings.39

To help address some of the barriers, the Parliament of Canada has adopted various measures to achieve a more gender-sensitive and family-friendly workplace for parliamentarians. These measures include:

Police-reported data show that women accounted for just over half (52%) of victims of violent crime in Canada in 2023.41 However, the most recent data from Statistics Canada’s General Social Survey – Canadians’ Safety show that in 2019, the self-reported rate of violent victimization among women was nearly double that of men.42 Part of the reason for this considerable difference between self-reported data and police-reported data is that nearly half of women’s self-reported incidents in 2019 were of sexual assault: this type of violent crime is “vastly underreported to police.”43 In 2019, 94% of victims had not reported the incident to police, meaning that police-reported data reflect only a small proportion of these crimes. One reason victims may not be reporting sexual assaults to police is that they are less likely to result in a charge than physical assaults: in 2019, only one out of every 19 reported sexual assaults led to a custodial sentence.44

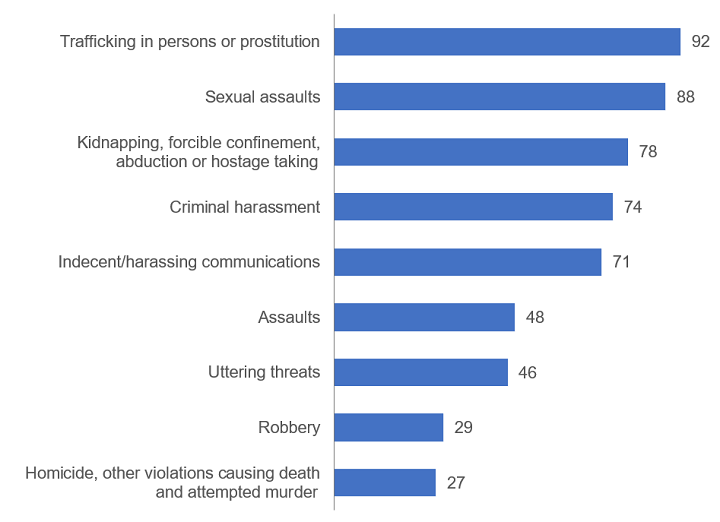

In addition, women are more likely than men to be the victims of certain criminal offences (e.g., sexual assault and trafficking in persons and prostitution). Figure 4 illustrates the gender breakdown of certain police-reported violent offences.

Figure 4 – Proportion of Women Among Victims of Selected Police-Reported Violent Crime, 2023 (%)

Source: Figure prepared by the Library of Parliament using data obtained from Statistics Canada, “Table 35-10-0050-01: Victims of police-reported violent crime and traffic violations causing bodily harm or death, by gender of victim and type of violation,” Database, accessed 14 January 2025.

Experiencing violence affects victims’ sense of personal safety. Many victims of unwanted sexual behaviour while in public – for example, sexual comments or attention – change their behaviour after the incident, such as avoiding certain places and changing routines to avoid certain people or situations.45

Finally, cisgender people may feel safer than gender-diverse minorities. Data from the First Nations Information Governance Centre collected in 2015 and 2016 showed that First Nations cisgender men reported feeling safe in their community at a significantly higher rate (86%) than their cisgender women counterparts (81%) and Two-Spirit or transgender counterparts (54%).46

Based on self-reported data, as of 2018, almost half of Indigenous women and girls over age 15 years had experienced sexual assault and 56% had experienced physical assault in their lifetime, compared to 33% and 34% of non-Indigenous women, respectively. Indigenous women with a disability or who had experienced homelessness were even more likely to have been the victim of a violent crime.47

Established in 2016, the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG) was mandated to investigate “all forms of violence against Inuit, Métis and First Nations women and girls, including 2SLGBTQQIA [Two-Spirit, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, questioning, intersex and asexual] people.”48 The MMIWG reports addressed historical aspects of discrimination and violence against Indigenous women, girls and members of 2SLGBTQQIA communities, and identified “four pathways that maintain colonial violence” that need to be addressed to achieve systemic change.

The findings and recommendations of the national inquiry’s final report included 231 Calls for Justice, directed at federal, provincial, territorial and municipal governments, institutions, social service providers, industries and all Canadians.49 In response, in 2021, the federal government, in collaboration with First Nations, Métis and Inuit partners, released a national action plan and the Federal Pathway, the Government of Canada’s plan to support systemic change to address the crisis of missing and murdered Indigenous women, girls and 2SLGBTQQIA people.50 In 2023, the government released the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act Action Plan 2023–2028, which provides a roadmap to implement the rights and principles affirmed in the Declaration and to advance reconciliation.51 Finally, in 2024, the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women issued findings on Canada’s implementation of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women. In its concluding observations, it welcomed the MMIWG reports but expressed concern with the slow progress in implementing the Calls for Justice and the lack of concrete measures to address the root causes of violence against Indigenous women.52

In 1995, the federal government committed to applying a gender lens, called Gender based Analysis (GBA), to assess the different impacts of legislation, policies and programs on women and men. In 2013, it expanded this approach to include additional identity factors in its analyses. Gender-based Analysis Plus (GBA Plus) allows for the examination of how federal programs, policies and initiatives are experienced differently by people with various intersecting identity factors, such as race, ethnicity, age, sexual orientation and disabilities.53

In recent years, several Indigenous women’s organizations in Canada have developed culturally responsive GBA Plus frameworks. These take an intersectional approach, considering different characteristics, factors and representations.54

The Gender Results Framework, introduced in the 2018 budget, tracks Canada’s progress with regard to gender equality. It has six pillars representing the priorities established by the federal government (education and skills development; economic participation and prosperity; leadership and democratic participation; gender-based violence and access to justice; poverty reduction, health and well-being; and gender equality around the world). Goals, objectives and indicators have been developed for the pillars. According to the government, the framework will contribute directly to the advancement of the UN’s SDGs.55

The Office of the Co-ordinator, Status of Women was established in 1970 in the Privy Council Office (PCO) in response to a recommendation contained in the report of the Royal Commission on the Status of Women in Canada. On 1 April 1976, the Office of the Co-ordinator, Status of Women became a departmental agency, which was replaced by the Department for Women and Gender Equality (WAGE) in December 2018. WAGE’s mandate is to “advance equality with respect to sex, sexual orientation, and gender identity or expression through the inclusion of people of all genders, including women, in Canada’s economic, social, and political life.”56

The LGBTQ2 Secretariat was established inside PCO in 2017, with a mandate to engage with organizations, protect the rights of 2SLGBTQI+ Canadians and address discrimination. In 2021, it was renamed the 2SLGBTQI+ Secretariat and was relocated to WAGE.57

In addition to the work of WAGE, all federal departments are directly or indirectly involved in implementing or promoting gender equality-related initiatives. The following are some examples of such initiatives:

Various federal Acts66 contain provisions aimed at promoting gender equality or establishing protections against gender-based discrimination, including:

In addition, the House of Commons Standing Committee on the Status of Women was established in 2004 to examine women’s issues, including “the way that gender inequality impacts women’s lives.”73 Other standing committees also undertake studies relating to issues of gender equality.

Finally, in 2015, the Standing Orders of the House of Commons were changed to include a code of conduct for members on sexual harassment, following a 2014 report by the Standing Committee on Procedure and House Affairs.74

While there have been significant gains with respect to gender equality in Canada over the past decades, inequalities remain, particularly for diverse groups of women, including Indigenous women, racialized women and women with disabilities, among others. Women face challenges in employment, in part relating to gender norms and discrimination. Fewer women are elected in federal politics than men. They also face higher rates of gender-based violence when compared to men. Federal legislation such as the Pay Equity Act and the Gender Budgeting Act and other initiatives aim to close such gaps.

© Library of Parliament