Any substantive changes in this Legislative Summary that have been made since the preceding issue are indicated in bold print.

Bill C-48, An Act respecting the regulation of vessels that transport crude oil or persistent oil to or from ports or marine installations located along British Columbia’s north coast (short title: Oil Tanker Moratorium Act), was introduced by the Minister of Transport in the House of Commons on 12 May 2017.1

The bill formalizes a crude oil tanker moratorium on the north coast of British Columbia and sets penalties for contravention of this moratorium.

The moratorium is in keeping with a 1972 federal government policy decision to impose a moratorium on crude oil tanker traffic through Dixon Entrance, Hecate Strait and Queen Charlotte Sound.2 This decision, while never formalized in legislation, was expressed in a House of Commons resolution stating that “the movement of oil by tanker along the coast of British Columbia from Valdez in Alaska to Cherry Point in Washington is inimical to Canadian interests especially those of an environmental nature.” 3

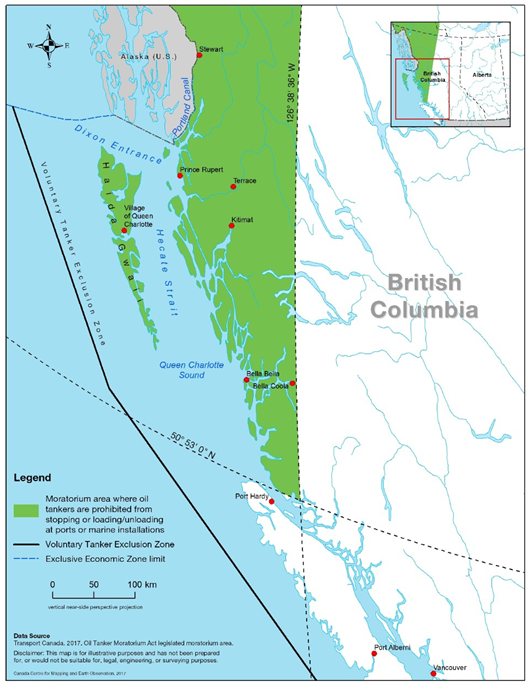

The tanker exclusion zone (see Figure 1) dates back to a 1988 voluntary agreement between the Canadian Coast Guard, the United States Coast Guard and the American Institute of Merchant Shipping (now the Chamber of Shipping of America).4 The purpose of the zone is “to keep laden tankers west of the zone boundary in an effort to protect the shoreline and coastal waters from a potential risk of pollution.” 5

Figure 1 - Area of the Oil Tanker Moratorium Set Out in Bill C-48

Source: Transport Canada, “Crude oil tanker moratorium on British Columbia’s north coast,” Backgrounder, 12 May 2017.

Recent debate around a tanker moratorium stems from the proposed Northern Gateway pipeline project, which would have transported 525,000 barrels per day of petroleum products from Bruderheim, Alberta, to Kitimat, B.C.6 In November 2016, the federal government directed the National Energy Board to dismiss the project, citing concerns about crude oil tankers “transiting through the sensitive ecosystem of the Douglas Channel, which is part of the Great Bear Rainforest.” 7

A legislated moratorium on crude oil tanker traffic on B.C.’s north coast was part of the mandate letter that the Prime Minister sent to the Minister of Transport at the start of the 42nd Parliament.8 The proposed moratorium is also part of the federal government’s broader Oceans Protection Plan.9

Bill C-48 contains 31 clauses. The following description highlights selected aspects of the bill; it does not review every clause.

Clause 2 sets out definitions that establish some of the main parameters of the bill. Three are worth noting: “crude oil” means “any liquid hydrocarbon mixture that occurs naturally in the earth,” regardless of whether it has been treated to render it suitable for transportation, while “persistent oil” is one of those listed in the schedule to the bill.10 The 14 persistent oils found in the schedule include partially upgraded bitumen (one of the products from the Alberta oil sands),11 but do not include liquefied natural gas, for example.12 Finally, a “marine installation” is defined as an installation on or connected to land that is used in the loading or unloading of oil.

Clause 2 also provides that the “Minister” within the meaning of the bill is the Minister of Transport.

The bill is binding on the provinces and the federal government (clause 3(1)), although vessels under the control of the Minister of National Defence are excluded from its application (clause 3(2)).

Clause 4 prohibits oil tankers carrying more than 12,500 metric tons of crude or persistent oil in their holds from undertaking certain activities at a port or marine installation in the designated area (shown in Figure 1). Specifically, such oil tankers must not moor or anchor (clause 4(1)) or unload or load oil (clauses 4(2) and 4(3)) in this area. Oil tankers that would contain 12,500 metric tons of crude or persistent oil after loading are prohibited from loading as well (clause 4(3)).

The prohibition against mooring or anchoring does not apply where a vessel stops in order to ensure its safety, assist a vessel in distress or obtain emergency medical assistance; or where it is directed to do so by the Minister of Fisheries and Oceans or the Minister of Transport (clause 5).

Clause 4 also contains specific measures to prevent individuals from attempting to circumvent the prohibitions contained in clauses 4(1) to 4(3). Clauses 4(4) and 4(5) prohibit any individual or vessel from transporting any crude or persistent oil between an oil tanker and a port or marine installation for the purposes of circumventing the oil tanker moratorium.

The Minister of Transport may exempt an oil tanker from the prohibitions listed in clauses 4(1) to 4(3) if he or she believes an exemption is essential for community or industry resupply or is otherwise in the public interest (clause 6(1)).

Clauses 7 to 16 establish a framework to promote compliance with the new Act.

Clause 7 requires the master of any oil tanker capable of carrying more than 12,500 metric tons of oil in its hold to provide the minister with certain information, including the name of the vessel and its country of registry, before arriving at a port or marine installation in the designated area (clauses 7(1) and 7(2)).

The pre-arrival information must be provided to the minister at least 24 hours before the tanker arrives at the port, or as soon as possible after the oil tanker leaves its previous port of call if the trip between its departure from that port and its anticipated arrival time is less than 24 hours (clause 7(3)).

If the minister has reasonable grounds to believe that the master of an oil tanker has failed to comply with the requirements of clause 7, he or she may direct the oil tanker not to moor or anchor at a port or marine installation that is within the designated area (clause 8).

Clause 9(1) enables the minister to designate a person or class of persons to administer and enforce the Act, and subsequent clauses provide those persons with a series of powers to enforce the Act. The powers contained in clause 10 relate to obtaining information, while those in clause 11 relate to entering a vessel, marine installation or place at a port and include, for example, the power to direct the master to stop the vessel or refrain from moving it (clause 11(5)).

Having obtained entry to the vessel or place, the designated person can undertake a range of activities, including conducting tests and taking photographs, to verify the vessel’s compliance with the Act (clause 11(3)).

Designated persons are not personally liable for anything they do or omit to do under the Act, provided they are acting in good faith (clause 9(3)).

Clauses 12 to 16 set out miscellaneous provisions relating to enforcement activities, some of which govern persons designated to enforce the Act and some of which address individuals subject to enforcement procedures. Of note, clause 12 articulates a duty to assist a designated person, while clause 15 prohibits deliberate obstruction of a designated person’s activities.

A person designated to enforce the Act may order the detention of a vessel if he or she has reasonable grounds to believe that the vessel has committed an offence under the Act (clause 17(1)).13 A detention order must be in writing and must be addressed to every person empowered to grant clearance to the vessel, and notice of a detention order must be served on the master of the vessel (clauses 17(2) and 17(3)).14

With certain exceptions, a person is not permitted to move a vessel that is subject to a detention order (clause 17(4)). Similarly, a person to whom a detention order is addressed is prohibited from granting clearance to a vessel that is subject to a detention order (clause 17(5)).

Certain exceptions apply to both of these prohibitions. Clause 17(6) provides that clearance can be granted where:

In addition, the minister may authorize a vessel that is subject to a detention order to be moved on application by the vessel’s authorized representative or the owner of the dock or wharf at which the vessel is located (clause 19(1)).

Clause 17(8) renders the authorized representative of a vessel that is subject to a detention order liable for all expenses incurred in respect of the detention.

The minister may apply to a court for authorization to sell a vessel that is subject to a detention order if the vessel has been charged with an offence under the Act within 30 days of the order and:

The bill also contains provisions to allow secured creditors to apply to the court to have their interests or rights in the vessel recorded by the court. Clause 21(1) requires the minister to give notice to various people, including certain creditors, of an application to sell a vessel. These creditors can, within 30 days of the notice being sent, apply to the court for an order declaring the nature and extent of their interests in the vessel (clause 22(1)). The court must grant the order if it is satisfied that an applicant is acting in good faith and is innocent of any involvement in the offence that gave rise to the detention order (clause 22(2)).

If the court authorizes the sale of a vessel and that vessel is sold, any surplus remaining from the proceeds of the sale, after deducting all fines, expenses and amounts due to secured creditors, must be paid to the owner of the vessel (clause 23(2)).

Clause 24 provides that the Governor in Council may, by regulation, amend the schedule to the new Act.

Clauses 25 to 30 make it an offence to contravene certain provisions of the Act, and they set out the punishments that apply.

Any person or vessel that contravenes the prohibition against carrying crude or persistent oil in the designated area is liable to the following fines:

Where a vessel commits an offence under clause 25, a number of individuals, including the owner and the operator of the vessel, can be considered party to and guilty of the offence and liable on conviction to the punishment provided for the offence (clause 28).

Under clause 26, any person who contravenes the following provisions is liable on summary conviction to a maximum fine of $1 million or to imprisonment for a maximum term of 18 months:

With two exceptions, a person or vessel cannot be found guilty of an offence if it can be established that the person, or the person who committed the act or omission that constitutes an offence for which a vessel is charged, exercised due diligence to prevent its commission (clause 30). Due diligence is not available as a defence against giving false information, or obstructing, or interfering with service or notice (clause 30(1)).

Summary conviction proceedings may not be commenced more than two years after the minister becomes aware of the subject matter of the proceedings.

Some stakeholders have expressed support for Bill C-48. For example, the Coastal First Nations - an alliance of First Nations on British Columbia’s north and central coasts, as well as on the archipelago of Haida Gwaii15 - published a news release stating that they “are pleased the proposed act prohibits large oil tankers carrying bitumen or synthetic crude oils from landing at any port in the region.” 16

In a news release, West Coast Environmental Law (WCEL) stated that Bill C-48 “marks a critical step forward in efforts to protect the north Pacific coast from the risk of oil spills.” 17 However, WCEL recommended that Transport Canada explain the rationale behind the 12,500-tonne threshold for the moratorium. It also suggested that the department release more information on past and present oil shipments in the region.18

WCEL also raised concerns about clauses 6(1) and 6(2) of Bill C-48, stating that they “could allow wide-scale and long-term exemptions from the oil tanker ban to be ordered behind closed doors without opportunity for public review and input.” 19

Some stakeholders are opposed to the moratorium itself. For example, the Chamber of Shipping of British Columbia has suggested that the proposed moratorium “contradicts … the federal government’s stated approach to environmental protection: evidence-based decision making” and “sends a very harmful signal to the international investment community.” 20

The Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers has argued that this proposed moratorium “could significantly impair Canada’s oil and natural gas resources from reaching new markets,” adding that such a moratorium also prevents Canada from “receiv[ing] fair market value for its resources.” 21

The Chief’s Council for the Eagle Spirit Energy Project - a First Nations-led energy corridor proposal that has the support of the affected communities in British Columbia and Alberta - has stated that “there has been insufficient consultation” on the proposed moratorium, which “does not have our consent.” 22

* Notice: For clarity of exposition, the legislative proposals set out in the bill described in this Legislative Summary are stated as if they had already been adopted or were in force. It is important to note, however, that bills may be amended during their consideration by the House of Commons and Senate, and have no force or effect unless and until they are passed by both houses of Parliament, receive Royal Assent, and come into force. [ Return to text ]

© Library of Parliament