Any substantive changes in this Legislative Summary that have been made since the preceding issue are indicated in bold print.

Bill C‑65, An Act to amend the Canada Labour Code (harassment and violence), the Parliamentary Employment and Staff Relations Act and the Budget Implementation Act, 2017, No. 1,1 was introduced in the House of Commons on 7 November 2017 by the Honourable Patty Hajdu, Minister of Employment, Workforce Development and Labour.

As indicated by its title, Bill C‑65 modifies the existing framework under the Canada Labour Code (Code)2 for the prevention of harassment and violence, including sexual harassment and sexual violence, in workplaces under federal jurisdiction (these workplaces are defined in section 1.2.1.1 of this Legislative Summary). It also amends the Parliamentary Employment and Staff Relations Act (PESRA)3 in order to expand these protections to parliamentary workplaces, “[without] limiting in any way the powers, privileges and immunities of the Senate and the House of Commons and their members.”4

Employment and Social Development Canada has indicated that the framework established by Bill C‑65 has three main pillars:

Bill C‑65 was referred to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Human Resources, Skills and Social Development and the Status of Persons with Disabilities (HUMA) on 29 January 2018. HUMA reported the bill with amendments on 23 April 2018 and the House concurred in that report on 7 May 2018.6

HUMA amended the bill to, among other things, include a definition for the term “harassment and violence” in the legislation, expand protections to former employees, institute mandatory training in the prevention of workplace harassment and violence, allow employees to bring their complaints to someone other than their supervisor, substitute the Minister of Labour for the Deputy Minister of Labour where parliamentary workplaces are concerned, as well as require annual reports containing statistical data on workplace harassment and violence along with five‑year reviews of the legislation.

On 7 June 2018, the bill was referred to the Standing Senate Committee on Human Rights (RIDR). RIDR reported the bill with amendments on 18 June 2018. The Senate concurred in that report and sent a message to the House of Commons on the same day.7

Notably, RIDR amended the bill to broaden the scope of the following aspects: the definition of “harassment and violence,” the purpose of Part II of the Code, and employer duties in relation to workplace harassment and violence. It also amended the bill to clarify that the protections afforded under the Canadian Human Rights Act (CHRA)8 will not be affected by the legislation, and to require that annual reports provide statistical data related to workplace harassment and violence according to prohibited grounds of discrimination. In its report, RIDR also included observations for further governmental action.

The House of Commons considered the Senate amendments and sent a message back to the Senate on 17 October 2018, in which it agreed with some of the amendments but disagreed with others. Notably, the House of Commons rejected Senate amendments to broaden the scopes of the definition of “harassment and violence” and of the purpose of Part II of the Code, along with certain annual reporting obligations.9 The Senate concurred with the House of Commons’ response on 24 October 2018, and the bill received Royal Assent the next day.

Recent studies have shown that harassment and violence are prevalent in Canadian workplaces, including those under federal jurisdiction. In a speech delivered before the House of Commons during the second reading of Bill C‑65, Minister Hajdu described the nature of harassment and violence in the workplace as follows:

[H]arassment and violence remain a common experience for people in the workplace; and Parliament Hill, our own workplace, is especially affected.

Parliament Hill features distinct power imbalances, which perpetuates a culture where people with a lot of power and prestige can use and have used that power to victimize the people who work so hard for us. It is a culture where people who are victims of harassment or sexual violence do not feel safe to bring those complaints forward. … It is like many other workplaces across Canada, especially those that have distinct power imbalances and a lack of strong policy that protects employees from harm. As it stands right now, people who have been victims of harassment or violence do not have suitable options for having their complaints heard, nor do they have options for resolving these very serious and often traumatic events. If they do come forward, they are often unsupported to manage the complex or difficult situations that they face as a result of the harassment that they have experienced.10

According to the Federal Jurisdiction Workplace Survey, in the year 2015 there were a total of 295 formal complaints of sexual harassment brought to the attention of the employer, 80% of which were from women. In addition, 1,601 incidents of workplace violence were reported in that year, with 60% of the injured or targeted employees having been men.11

Public consultations led by the Employment and Social Development Canada between July 2016 and April 2017 on the topic of harassment and sexual violence in workplaces under federal jurisdiction have shed further light on these issues. These consultations took the form of an online survey and a series of meetings with stakeholders, who were also invited to make written submissions. The online survey, in particular, revealed the following key findings:

Furthermore, research carried out by Abacus Data during the fall of 2017 found that approximately 1 in 10 Canadians say sexual harassment is “quite common” in their workplace, with another 44% indicating that it is infrequent, but happens. The research also indicates that younger women are more likely to experience harassment than older women, and that sanctions are rarely applied against harassers.13

One of the ideas suggested by participants in the federal consultations was to modify the current legislative framework to reduce workplace harassment and violence and speed up the internal resolution of complaints. Notably, some stakeholders recommended integrating sexual harassment provisions that are currently under Part III (Labour Standards)14 of the Code into Part II (Occupational Health and Safety) of that same Act, with the caveat that sexual harassment would have to be differentiated from workplace violence, given privacy considerations.15

Stakeholders also suggested adopting a clear definition of the term psychological violence or of a continuum of psychologically violent behaviour, which would need to be broad enough to include many forms of harassment including homophobia and gender‑based violence. In addition, stakeholders highlighted the importance for employers to have clearly defined workplace policies on harassment and violence, addressing, for example, how to report incidents.16

The current legal framework for dealing with harassment and violence in federally regulated workplaces is set out under parts II and III of the Code and related regulations. Bill C‑65 consolidates this framework under Part II, such that workplace harassment and violence, including complaint resolution, is primarily addressed within the context of occupational health and safety.

Under Part II (Occupational Health and Safety) of the Code, employers must ensure that the health and safety at work of every employee is protected, while employees must take all necessary precautions to ensure their own health and safety and that of their colleagues, among other duties.17 In addition, employees have the right to be informed of known or foreseeable workplace hazards and to be provided with instructions in this regard, to participate as health and safety representatives or committee members, to use the internal complaint resolution process, and to refuse dangerous work.18

The issue of workplace violence, which includes harassment, is therefore addressed under Part II of the Code.19 Notably, the current framework requires employers to “take the prescribed steps to prevent and protect against violence in the work place.”20 The term “work place violence” is defined under Part XX (Violence Prevention in the Work Place) of the Canada Occupational Health and Safety Regulations as “any action, conduct, threat or gesture of a person toward an employee in their work place that can reasonably be expected to cause harm, injury or illness to that employee.”21

Part XX of the regulations also sets out the obligations of employers with regard to violence prevention in the workplace. These obligations (which include developing a workplace violence prevention policy; appointing a “competent person” to investigate occurrences of workplace violence; as well as providing information, instruction and training on workplace violence) must be carried out in consultation with, and with the participation of, the health and safety committee or representative.22 Employers (and any other person) who contravene a provision under Part II of the Code are guilty of an offence and liable on conviction to fines and/or imprisonment.23

Part II of the Code and related regulations apply in relation to employment in federally regulated businesses and industries, including interprovincial and international services (such as railways, road and air transport, and shipping services), radio and television broadcasting, telephone and cable systems, banks, most federal Crown corporations, as well as private businesses necessary to the operation of a federal Act. The federal public service and persons employed by the public service, as well as interns employed in the above‑noted sectors, are also covered under Part II of the Code.24

Under Part II of the Code, an employee must make a complaint to a supervisor when the employee believes, on reasonable grounds, that there has been a contravention of this Part or that there is likely to be a workplace‑related accident or injury to health. Subject to certain exceptions such as the right to refuse dangerous work, the complaint must be made before exercising any other recourse available under this Part. The parties must attempt to resolve the complaint between themselves as soon as possible.

An employee or supervisor may refer an unresolved complaint to a chairperson of the workplace committee or to the health and safety representative, to be jointly investigated by an employee and employer member of the workplace committee, or the health and safety representative and a person designated by the employer.

Within the context of workplace violence, Part XX of the regulations stipulates that the employer must appoint a “competent person” to investigate the unresolved matter, unless:

The employer must provide the competent person with any relevant information that may be lawfully disclosed and does not reveal the identity of affected persons without their consent. Upon completion of the investigation, the competent person must provide the employer with a written report containing conclusions and recommendations. The employer is required to forward a redacted copy of this report to the workplace committee or the health and safety representative, as well as adapt or implement measures to prevent a recurrence of the workplace violence. The competent person must be impartial; have knowledge, training and experience in workplace violence issues; and be familiar with the relevant legislation.

In certain circumstances (such as when the employer does not agree with the results of the investigation or fails to take action to resolve the matter, or when the persons who conducted the investigation cannot agree on whether the complaint is justified), Part II of the Code provides that the employer or the employee may refer the complaint to the Minister of Labour (Minister). On completion of the Minister’s investigation, the Minister may issue directions to the employer and the employee or, if appropriate, recommend that the parties resolve the matter between themselves.25

An employer, employee or trade union that disagrees with a direction issued by the Minister under Part II of the Code may appeal the direction in writing to an appeals officer,26 though the relevant decision‑maker will change with the coming into force of the relevant provisions in the Budget Implementation Act, 2017, No. 1.27 At that time, the powers, duties and functions of the appeals officers under Part II of the Code will be transferred to the Canada Industrial Relations Board (CIRB).28

In addition, employees may make a complaint to either the CIRB or the Federal Public Sector Labour Relations and Employment Board (FPSLREB) in relation to employer reprisals that resulted when employees exercised rights relating to workplace health and safety under Part II of the Code. The CIRB and the FPSLREB can hear the complaint under their own rules of procedure.29

The Code addresses sexual harassment in the workplace under Division XV.1 of Part III (Labour Standards). Sexual harassment is defined under this part as

any conduct, comment, gesture or contact of a sexual nature

- that is likely to cause offence or humiliation to any employee; or

- that might, on reasonable grounds, be perceived by that employee as placing a condition of a sexual nature on employment or on any opportunity for training or promotion.30

Under the current framework, employees are entitled to employment that is free from sexual harassment, and employers are required to make “every reasonable effort” to ensure that employees are not subjected to sexual harassment. As part of this duty, employers are required to issue a policy statement concerning sexual harassment, in consultation with employees or their representatives, and make employees aware of such policy statements.31

The primary objective of Part III of the Code is to establish and protect workers’ rights to fair and equitable conditions of work. Employers and employees are therefore required to meet these standards, with those who contravene any provision under this Part being guilty of an offence under the Code and subject to fines. Unlike Part II of the Code, Part III does not apply to federal public service employees or to interns.32

PESRA is the federal legislation that governs the labour relations of parliamentary institutions. While provisions regarding the application of parts II and III of the Code have been part of PESRA since it was enacted on 27 June 1986, they have not been brought into force.

Specifically, Part II of PESRA provides for the application of Part III of the Code, while Part III of PESRA contains provisions regarding the application of Part II of the Code. Coverage under the Code is in relation to a specified list of parliamentary employers and their employees.

As such, currently, the House of Commons Policy on Preventing and Addressing Harassment33 and the Senate Policy on the Prevention and Resolution of Harassment in the Workplace34 are the primary mechanisms for dealing with workplace harassment in the parliamentary context.

The CHRA also protects employees from harassment (including sexual harassment), based on one or more of the prohibited grounds of discrimination.35 The prohibited grounds of discrimination are outlined in the legislation and include sex, sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, genetic characteristics, marital status, family status, race, colour, national or ethnic origin, religion, age, and disability.36

According to the Canadian Human Rights Commission, federally regulated employers are responsible for any harassment that takes place in the workplace. As a result, they must have an anti‑harassment policy in place and take appropriate action against any employee who harasses someone else. The CHRA also provides a framework for the resolution of discrimination-related complaints.37

Furthermore, the Criminal Code 38 offers additional protections to any victim of harassment and violence, including employees in workplaces under federal jurisdiction. Among others, physical or sexual assault, as well as criminal harassment, are considered punishable offences under the legislation. According to the Honourable Patty Hajdu, “the proposed legislation in no way replaces or takes precedence over the Criminal Code of Canada [as] [s]ome actions and offences require law enforcement intervention, and complainants always have the right to go to the police to report incidents.”39

Clause 1 of Bill C‑65 broadens the scope of the purpose of Part II of the Code. Indeed, while the current purpose of Part II is to prevent workplace-related “accidents and injury to health,” the amendments provide for the prevention of workplace-related “accidents, occurrences of harassment and violence, and physical or psychological injuries and illnesses” (amended section 122.1).40

Clause 2 of the bill expands the application of Part II of the Code in section 123 to cover ministerial staff and their employer. The term “ministerial staff” includes individuals who are appointed by a minister as their executive assistants as well as other persons required in a minister’s office. Coverage under Part II of the Code, however, is not extended to persons appointed by the Leader of the Opposition in the Senate or in the House of Commons (new section 123(2.1)).

Clause 0.1 of the bill adds the following definition to the interpretation provision of Part II of the Code:

harassment and violence means any action, conduct or comment, including of a sexual nature, that can reasonably be expected to cause offence, humiliation or other physical or psychological injury or illness to an employee, including any prescribed action, conduct or comment (amended section 122(1)).41

This definition may nevertheless be completed by way of regulation. Indeed, clause 14 of the bill expands the powers of the Governor in Council to make regulations defining the terms “harassment” and “violence” for the purposes of Part II of the Code (new section 157(1)(a.01)).

Clause 3 of the bill amends section 125 of the Code, which sets out the specific duties of employers under Part II, to include duties related to workplace harassment and violence as well as to broaden the scope of those duties related to access to information.

Clause 3 of the bill provides that employers are required to take prescribed measures to prevent and protect, not only against workplace violence as already provided for in the legislation, but now also against workplace harassment. They are now also required to respond to occurrences of workplace harassment and violence, and to offer support to affected employees (amended section 125(1)(z.16)).42

In addition, employers must investigate, record and report, not only all accidents, occupational illnesses and other hazardous occurrences known to them, but now also occurrences of harassment and violence, in accordance with the regulations (amended section 125(1)(c)).43

These duties also apply in relation to former employees, if the occurrence of workplace harassment and violence becomes known to the employer within three months of the employee ceasing employment. This timeline, however, may be extended by the Minister in the prescribed circumstances (new sections 125(4) and 125(5)).44

The Governor in Council is given regulation-making powers with respect to the investigations, records and reports referred to above, as well as in relation to employer obligations toward former employees (new sections 125(3) and 125(6)).

Clause 3 of the bill further stipulates that employers are required to ensure that all employees are trained in the prevention of workplace harassment and violence and to inform them of their rights and obligations in this regard (new section 125(1)(z.161)). Employers themselves must also undergo training in the prevention of workplace harassment and violence (new section 125(1)(z.162)).45

Finally, employers must also ensure that the person they designate to receive complaints related to workplace harassment and violence has the requisite knowledge, training and experience (new section 125(1)(z.163)).46

Under clause 3 of the bill, certain duties are streamlined related to posting certain information in a conspicuous place (such as a copy of Part II of the Code and a statement of the employer’s general policy regarding occupational health and safety), and making a copy of the regulations made under Part II readily available to employees in printed or electronic format. All specified information must now be made available in both formats (amended section 125(1)(d); section 125(1)(e) is repealed).47

Where any of the specified information is made available in an electronic format, employers must offer training to employees to ensure they can access it as well as provide a printed copy when one is requested. This replaces a similar duty regarding employee access to a copy of the regulations (amended section 125(1)(f)).

Clause 5 of the bill amends section 127.1 of the Code to broaden the scope of the internal complaint resolution process under Part II, specifically in relation to workplace harassment and violence.

While currently an employee must make a complaint to a supervisor if the employee believes, on reasonable grounds, that there has been a contravention of Part II of the Code, or that there is likely to be a workplace-related “accident or injury to health,” the amendments require employees to also make a complaint when there is a risk of workplace-related “illnesses” (amended section 127.1(1)).

Where the complaint relates to workplace harassment and violence, however, the employee may make the complaint to either their supervisor or to the person designated in the workplace harassment and violence prevention policy (new section 127.1(1.1)). The complaint may be made orally or in writing (new section 127.1(1.2)). The employee and the supervisor or designated person must try to resolve the complaint among themselves as soon as possible (amended section 127.1(2)).48

Further, while an unresolved complaint may be referred for investigation to a chairperson of the workplace committee or to the health and safety representative, those relating to an occurrence of harassment and violence may now be referred directly to the Minister (amended section 127.1(3) and new section 127.1(8)(d)). The Minister must investigate the complaint unless the Minister is of the opinion that:

Where the Minister refuses to investigate the complaint based on the reasons outlined above, the Minister must notify the employer and the employee in writing as soon as feasible (new section 127.1(9.1)).

Where the Minister agrees to conduct an investigation into an unresolved complaint related to an occurrence of harassment and violence, the Minister may combine this investigation with an ongoing one that deals with substantially the same issues and involves the same employer. In this case, the Minister may issue a single decision (new section 127.1(9.2)).50

These provisions also apply in relation to former employees who make a complaint relating to an occurrence of workplace harassment and violence, within the prescribed time. This timeline, however, may be extended by the Minister in the prescribed circumstances (new sections 127.1(12) and 127.1(13)).51

Clauses 6 to 11 of the bill amend various Code provisions dealing with workplace health and safety committees, policy health and safety committees, as well as health and safety representatives, in order to limit the instances where an employer may be exempt from establishing a committee and to set out privacy requirements in relation to workplace harassment and violence.52

Clause 7 of the bill repeals sections 135(3) to 135(5) of the Code. These provisions stipulate that the Minister may, at the employer’s request and after considering specified factors, exempt employers from the requirement to establish a workplace committee where the Minister is satisfied that the nature of the work performed is “relatively free from risks to health and safety.”53

Clause 7 of the bill further provides that, only where a collective agreement or other agreement between employer and employees exists, under which a committee with responsibility for matters related to occupational health and safety has been established, may the Minister exempt the employer from the requirement to establish a workplace committee. In other words, under the new approach, exemptions will be allowed only in circumstances where employers have an alternative that meets the same occupational health and safety needs.

While this particular exemption is already provided for in the legislation, employers must now submit a request in this regard (amended section 135(6)(a)), which must be posted in a place that is visible to the employees, until such time as the employees are notified of the Minister’s decision (new section 135(6.1)).

Clauses 6, 7 and 10 of the bill provide that health and safety committees and representatives are prohibited from participating in an investigation related to occurrences of workplace harassment and violence. They may nevertheless participate in investigations into work refusals relating to workplace harassment and violence under sections 128 and 129 of the Code, which set out the framework around an employee’s right to refuse dangerous work (new sections 134.1(4.1), 135(7.1) and 136(5.1)).

In addition, in accordance with clauses 8 and 11 of the bill, health and safety committees and representatives cannot be provided with or have access to “any information that is likely to reveal the identity of a person who was involved in an occurrence of harassment and violence in the work place,” without that person’s consent. This restriction, however, does not apply to an employer who gives a copy of an appeals officer’s decision, reasons or direction to the workplace committee or the health and safety representative; or where information on work refusals carried out under sections 128 and 129 of the Code is provided to a health and safety committee (new sections 135.11(1) and 135.11(2), and 136.1(1) and 136.1(2)).

Finally, under clause 9 of the bill, the regulation-making powers of the Governor in Council are expanded to allow for the making of more specific regulations requiring health and safety committees to submit an annual report of their activities. Notably, the Governor in Council may now make regulations specifying the information to be contained within these reports and the manner in which these reports must be submitted, not just the recipient and the deadline (amended section 135.2(1)(g)).

Clause 2.1 of the bill clarifies that the protections afforded under the CHRA will not be affected by any of the provisions under Part II of the Code (new section 123.1).54 This includes the right to seek redress related to occurrences of harassment or sexual harassment under the CHRA.

Clause 11.1 of the bill requires the Minister to prepare and publish an annual report containing statistical data on “harassment and violence in work places to which this Part applies,” including information that is categorized according to prohibited grounds of discrimination under the CHRA. The report, however, must not contain information likely to reveal an affected person’s identity (new section 139.1).55

The Minister is also required to conduct five‑year reviews on the application of provisions related to workplace harassment and violence under Part II of the Code. The report produced in this regard must be tabled in each House of Parliament within 15 sitting days following its completion (new sections 139.2(1) and 139.2(2)).56

Clauses 15 and 17 of the bill further expand the regulation-making powers of the Governor in Council. Specifically, the Governor in Council may now make regulations to allow for:

Unless repealed earlier, regulations made in accordance with these provisions are to be repealed five years from the coming into force of the regulations (new sections 162 and 297).

As mentioned above, Bill C‑65 consolidates the current legal framework for dealing with harassment and violence under Part II of the Code. Clause 16 of the bill therefore repeals Division XV.1 of Part III of the Code, which contains provisions related to sexual harassment in the workplace. Division XV.1 is explained in section 1.2.1.3 of this Legislative Summary.

Clause 20 of the bill provides that, with the exception of clause 17, amendments to the Code will come into force on a day to be fixed by order of the Governor in Council.

Clause 17 will also come into force on a day to be fixed by order of the Governor in Council. However, this day must not be earlier than the day on which the relevant provisions from the Budget Implementation Act, 2017, No. 1 establishing Part IV of the Code come into force.

Clause 21 of the bill replaces Part III of PESRA, which contains provisions related to occupational health and safety. Specifically, it expands the scope of the interpretation and application provisions (which, as mentioned above, have not yet been brought into force), and introduces new ones with regard to the complaint resolution process. It also clarifies that the protections afforded under the CHRA are not affected by any of the provisions under Part III of PESRA.

Clause 21 of the bill amends the interpretation provision in Part III of PESRA with regard to occupational health and safety, by adding definitions for the terms “Board,” “employee” and “employer” (amended section 87(1)).

Specifically, “Board” is defined as the FPSLREB. This is the same definition that applies under Part I (Staff Relations) of PESRA. It ensures that appeals considered under different parts of PESRA are heard by the same adjudicative body.

Further, “employee” is defined as a person employed by one of the employers listed below. The Clerk of the Senate, the Clerk of the House of Commons, the Usher of the Black Rod, the Sergeant‑at‑Arms, and the Law Clerk and Parliamentary Counsel of the House of Commons are also included under this definition.

The term “employer,” which is currently defined under Part II of PESRA as including the employers listed in bullets a) to h) below, is expanded to include those listed in bullets i) and j). It also includes any person who acts on behalf of an employer. The expanded definition includes the following employers:

The bill also amends PESRA to incorporate by reference the occupational health and safety provisions in Part II of the Code, subject to certain exceptions related to the enforcement of orders and injunction proceedings to ensure parliamentary privilege is respected. The application of Part II of the Code is therefore expanded to include the newly defined parliamentary employers and employees, as well as interns working in parliamentary workplaces.

In addition, within the parliamentary context, matters related to Part II of the Code may be heard and determined only by a member of the FPSLREB. This means that the FPSLREB will not be able to hire an external consultant or adjudicator to hear matters relating to PESRA.

Finally, Part I of PESRA, which sets out the provisions regarding staff relations in parliamentary workplaces, applies in relation to matters brought before the FPSLREB under Part II of the Code, subject to modifications to ensure parliamentary privilege is respected (amended section 88(1)).58

The bill provides for the application to parliamentary workplaces of the complaint resolution process set out under Part II of the Code, subject to certain modifications to better suit the parliamentary context.

The bill provides that the Minister must notify the Speakers of the Senate and/or the House of Commons of the Minister’s intention to enter a workplace in accordance with the powers established under Part II of the Code. In addition, notification must also be given, as soon as possible, after the Minister commences an investigation or issues a direction under Part II of the Code (new section 88.1).

In turn, the FPSLREB must notify the Speakers of the Senate and/or the House of Commons, as soon as possible, after:

In the case of notification of an appeal brought before the FPSLREB, the Speaker of the Senate or the House of Commons may request specified information as well as present evidence and make representations in the appeal (new section 88.2(2)).

If a direction issued by the Minister to an employer or an employee under Part II of the Code is not complied with or appealed within the specified period of time, the Minister must ensure that the direction is tabled in the Senate and/or the House of Commons. This must be done “within a reasonable time” after the expiry of the latest of the periods for compliance and appeal (new section 88.3).

If, however, the Minister considers that immediate action must be taken to prevent a contravention of Part II of the Code, the Minister must provide a copy of the direction issued to an employer or employee to the Speakers of the Senate and/or the House of Commons. If that direction is not complied with within the specified period of time, the Minister may seek its tabling in the Senate and/or the House of Commons, even if this is before the expiry of the appeal period (new section 88.4).

Similarly, if an order, decision or direction made by the FPSLREB in relation to an employer or an employee under Part II of the Code is not complied with within the specified period of time, the FPSLREB must ensure it is tabled in the Senate and/or the House of Commons. This must be done “within a reasonable time” following the request from the Minister or any affected persons in this regard (new section 88.5).

Where an occupational health and safety incident involves a member of the Senate or the House of Commons, or their employees, the Deputy Minister of Labour must exercise the powers and perform the duties and functions of the Minister under Part III of PESRA and under Part II of the Code. This includes ensuring that the direction referred to above is tabled in the Senate and/or the House of Commons (new sections 88.01(1) and 88.01(2)).59

The bill further stipulates that the provisions made under PESRA with regard to occupational health and safety cannot be used to limit “the powers, privileges and immunities” of the Senate, the House of Commons or their members. Neither can they interfere, directly or indirectly, with the business of the Senate or the House of Commons (new section 88.6).

The FPSLREB is required to submit an annual report of its activities under Part III of PESRA and under Part II of the Code as they relate to employers and employees.60

This annual report must be submitted to the minister designated under the Federal Public Sector Labour Relations and Employment Board Act,61 who will then be responsible for tabling it in each House of Parliament within 15 sitting days of its receipt (new section 88.7).

Further, the minister designated under PESRA62 is required to conduct five‑year reviews on the application of the provisions related to workplace harassment and violence under Part III of the legislation. The report produced in this regard must be tabled in each House of Parliament within 15 sitting days following its completion (new sections 88.8(1) and 88.8(2)).63

Clause 23 of the bill provides that clause 21 comes into force on the day on which Bill C‑65 receives Royal Assent, or on the day certain provisions from Budget Implementation Act, 2017, No. 1 regarding amendments to the Code come into force, whichever is later.

The federal government has indicated that it intends for Bill C‑65 to come into force within two years of Royal Assent. In order to support the implementation of Bill C‑65, the government has also announced that Part XX of the Canada Occupational Health and Safety Regulations will be amended.64

During the regulatory development process, the government will be consulting with Canadians on a series of proposals built around the three main pillars of the legislation: prevention, response and support. The proposed regulatory framework has been outlined in a consultation paper and includes requirements for the following:

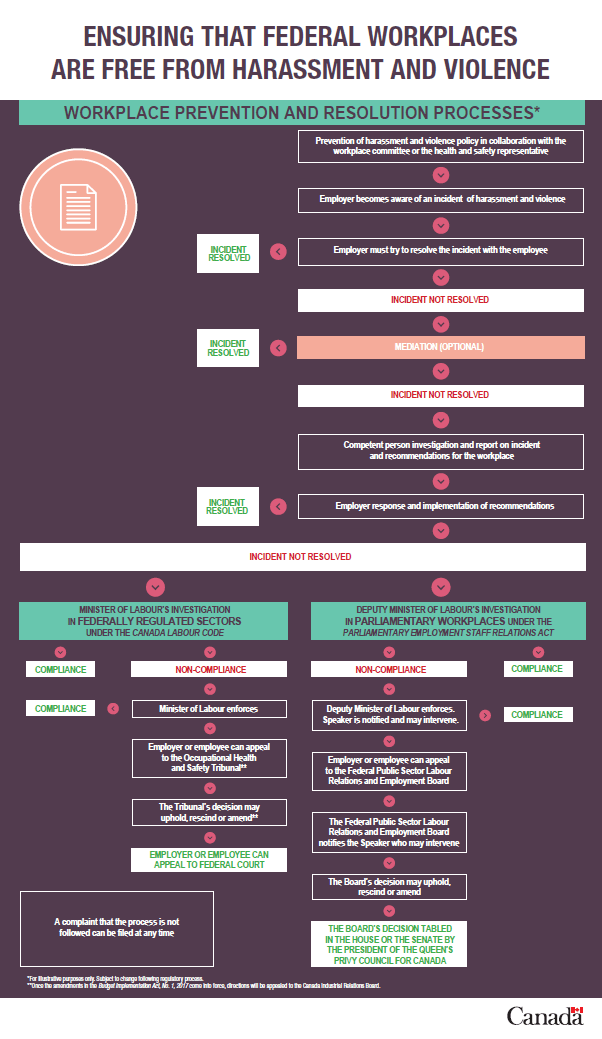

Figure A.1 – Workplace Harassment and Violence Prevention and Resolution Processes*

These are the initial steps in the federal workplace harassment and violence prevention and resolution processes:

At the end of these steps, one of the following occurs:

If the incident is not resolved, you have the option of mediation or an investigation by a competent person, who would report on the incident with recommendations for the workplace. If you choose mediation and it does not solve the issue, you would move on to the investigation.

Minister of Labour's investigation in federally regulated sectors under the Canada Labour Code

Deputy Minister of Labour's investigation in parliamentary workplaces under the Parliamentary Employment Staff Relations Act

A complaint that the process is not followed can be filed at any time.

Notes:

Source: Employment and Social Development Canada.

* Notice: For clarity of exposition, the legislative proposals set out in the bill described in this Legislative Summary are stated as if they had already been adopted or were in force. It is important to note, however, that bills may be amended during their consideration by the House of Commons and Senate, and have no force or effect unless and until they are passed by both houses of Parliament, receive Royal Assent, and come into force. [ Return to text ]

harassment occurs when someone:For more information, see Canadian Human Rights Commission, Your Guide to Understanding the Canadian Human Rights Act, p. 3. [ Return to text ]

- offends or humiliates you physically or verbally

- threatens or intimidates you

- makes unwelcome remarks or jokes about your race, religion, sex, age, disability, etc.

- makes unnecessary physical contact with you, such as touching, patting, pinching or punching – this can also be assault.

© Library of Parliament