Any substantive changes in this Library of Parliament Legislative Summary that have been made since the preceding issue are indicated in bold print.

Bill C-5, An Act to amend the Criminal Code and the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act,1 was introduced in the House of Commons on 7 December 2021 by Minister of Justice David Lametti. It is almost identical to Bill C-22, An Act to amend the Criminal Code and the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act2 which was introduced in the 43rd Parliament, but did not pass before the end of that Parliament. A Charter Statement for Bill C-5 was tabled in the House of Commons on 16 December 2021.3

The bill passed second reading in the House of Commons on 31 March 2022 and was referred to the Standing Committee on Justice and Human Rights, which adopted the bill with amendments.

Bill C-5:

Mandatory minimum sentences of imprisonment are legal requirements set out in criminal statutes that specify the minimum term of imprisonment for an offender convicted of an offence. Ordinarily, judges have broad discretion to determine an appropriate sentence for an offence; they are guided by the sentencing principles contained in the Code and give consideration to aggravating or mitigating factors and the circumstances of the particular offender.7 Mandatory minimum sentences of imprisonment limit judicial discretion by requiring a sentence of imprisonment of a particular length, regardless of these factors (though discretion to impose a longer sentence, up to the maximum sentence, is maintained).

Mandatory minimum sentences have attracted some controversy and have been the subject of constitutional challenges in Canada. Proponents argue that mandatory minimum sentences allow for predictability in sentencing. They argue they can reduce disparities in sentencing by promoting similar terms for all offenders, and they can act as deterrents to criminal offending by enabling citizens to more accurately gauge the range of penalties they face if they commit an offence.8 Opponents argue that they unjustly limit judicial discretion, have little or no deterrent effect, and can result in disproportionate sentencing and over-incarceration, and the disproportionate imprisonment of marginalized populations.9

Bill C-5 removes mandatory minimum sentences for 14 offences in the Code and all offences in the CDSA. The offences in the Code for which mandatory minimum sentences are removed predominantly relate to firearms or other weapons.

A 2017 analysis by Statistics Canada showed that mandatory minimum sentences of imprisonment for specific firearms offences resulted in “a notable increase in the length of custody sentences”10 after longer mandatory minimum sentences were introduced, suggesting that mandatory minimum sentences do, in fact, have an impact on sentence length and can result in longer terms of imprisonment.

When sentencing a person convicted of an offence, judges are required by the Code to ensure that the sentence imposed is “proportionate to the gravity of the offence and the degree of responsibility of the offender.”11 Chief Justice Beverley McLachlin, writing for the majority of the Supreme Court of Canada, expressed in R. v. Lloyd, that

mandatory minimum sentences for offences that can be committed in many ways and under many different circumstances by a wide range of people are constitutionally vulnerable because they will almost inevitably catch situations where the prescribed mandatory minimum would require an unconstitutional sentence.12

This vulnerability to constitutional challenge is confirmed by data from the Department of Justice Canada indicating that as of 3 December 2021, they are tracking 217 challenges of mandatory minimum sentences under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms (the Charter).13 This type of challenge accounts for 34% of all constitutional challenges to the Code that are being tracked by the Department.14 Furthermore, the Department of Justice Canada reports that among these challenges tracked in the last decade, 69% of challenges to drug offences and 48% of challenges to firearms offences were successful. When a section of the Code is held to violate the Charter, that section can be declared of no force and effect.15 This means that the unconstitutional provision, to the extent of its inconsistency with the Charter, is no longer considered applicable law in the jurisdiction in which it was so declared. When such a declaration of invalidity is made by the Supreme Court of Canada, the unconstitutional provision is of no force and effect throughout Canada. Where an appellate court in a province makes such a declaration, the unconstitutional provision is of no force and effect in that province; however, it may continue to be applied in other provinces, making the application of the law inconsistent across the country.

In several cases, provisions imposing mandatory minimum sentences of imprisonment have been held to violate section 12 of the Charter, which guarantees that “[e]veryone has the right not to be subjected to any cruel and unusual treatment or punishment.”16 Where a mandatory minimum sentence provision would require a judge to impose a sentence that is “grossly disproportionate”17 to the gravity of the offence, the blameworthiness of the offender and the harm caused by the commission of the offence, that sentence may be held to violate section 12 of the Charter.18 Some of the mandatory minimum sentences of imprisonment repealed by Bill C-5 have previously been held to be unconstitutional and struck down by Canadian courts, including appellate courts.19 Other mandatory minimum sentences of imprisonment have been upheld following constitutional challenges.20

Concerns have been raised by some academics and civil society organizations that mandatory minimum sentences of imprisonment can have a disproportionate impact on Indigenous and racialized persons and may contribute to the over-incarceration of these populations.21

During the period from 2007–2008 to 2016–2017, white offenders comprised 60% of all federal offenders, while Indigenous people comprised 23%, and Black and “other visible minority offenders,” or racialized offenders, comprised 9% each of all federal offenders. Statistics Canada’s 2011 National Household Survey found that 2.9% of the Canadian population self identified as Black, 4.3% as Indigenous and 16.2% as members of an “other” visible minority group in that year.22

One reason cited by the Department of Justice Canada for removing mandatory minimum sentences through Bill C-5 is to

maintain public safety while ensuring that responses to criminal conduct are fairer and more effective. These proposed amendments are an important step in addressing systemic issues related to existing sentencing policies.23

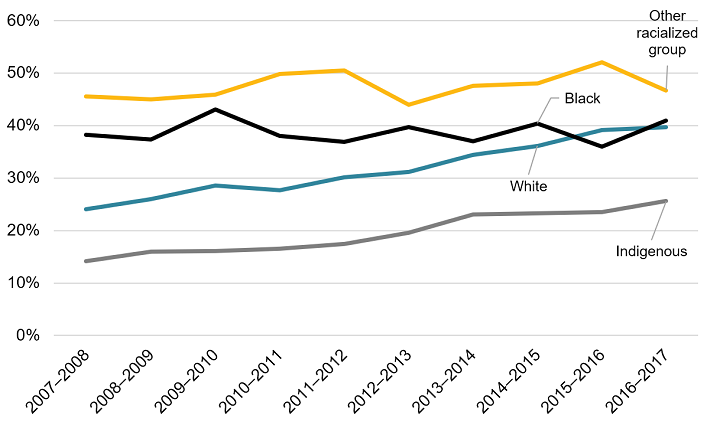

According to data from Correctional Service Canada, over a 10-year period from 2007–2008 to 2016–2017, Black and other racialized offenders were disproportionately admitted into federal correctional facilities after receiving a mandatory minimum sentence of imprisonment. Over that 10-year period, the percentage of offenders admitted into custody who had received a mandatory minimum sentence of imprisonment varied considerably by race:

The proportion of Indigenous offenders admitted into a correctional facility for an offence that is subject to a mandatory minimum sentence of imprisonment increased over the same 10-year period from 14% to 26%, and the proportion of white offenders increased from 24% to 40% over that period. The proportions of Black offenders and offenders from other racialized groups remained stable over this period.

Figure 1 – Proportion of Offenders in Each Racial Group Admitted to Federal Custody for Offences Punishable by a Mandatory Minimum Sentence, 2007–2008 to 2016–2017

Source: Figure prepared by the Library of Parliament using data obtained from Department of Justice Canada, “The Impact of Mandatory Minimum Penalties on Indigenous, Black and Other Visible Minorities,” JustFacts, Research and Statistics Division, October 2017.

Bill C-5 removes several mandatory minimum sentences of imprisonment for offences involving firearms and drugs. Indigenous and racialized offenders are overrepresented among those convicted of some drug- and firearm-related offences.

For example, with respect to drug offences, data from Correctional Service Canada compiled from 2007–2008 to 2016–2017 suggests that Black offenders were disproportionately admitted into federal correctional facilities during that period for violating section 6 of the CDSA on importing and exporting which carries a mandatory minimum sentence that is removed by Bill C-5. Black offenders made up 42% of these admissions in the 10 years studied, with the proportion of admissions increasing over time from 33% in 2007–2008 to 43% in 2016–2017. Furthermore, the proportion of Indigenous people among offenders admitted into custody following a conviction under section 6 of the CDSA during the same period rose from 1% to 12.5%. At the same time, the proportion of white offenders decreased from 38% to 25%. White offenders were more likely to be admitted for trafficking under section 5 or for production under section 7.24

| Race | 2007–2008 (%) | 2016–2017 (%) | Average Over the Period (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| White | 38 | 25 | 30 |

| Indigenous | 2 | 12 | Not available |

| Black | 33 | 43 | 42 |

Note: No statistics for other racialized groups were included on this topic in the source publication.

Source: Table prepared by the Library of Parliament using data obtained from Department of Justice Canada, “The Impact of Mandatory Minimum Penalties on Indigenous, Black and Other Visible Minorities,” JustFacts, Research and Statistics Division, October 2017.

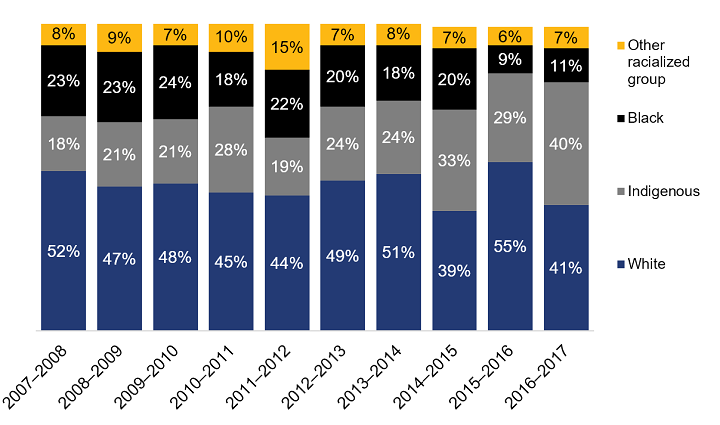

With respect to firearms offences, data suggest that Black offenders admitted to federal correctional facilities were overrepresented among those convicted of various firearms offences that carry a mandatory minimum sentence, though to a lesser extent in the later years of the 10-year period from 2007–2008 to 2016–2017 than in the earlier years of the same period. Many of the mandatory minimum sentences of imprisonment removed by Bill C-5 – including those contained in sections 85, 99, 100, 244 and 344 of the Code – are for offences for which Black offenders are disproportionately convicted. Indigenous offenders are also overrepresented among those serving a federal sentence for a firearms offence that has an applicable mandatory minimum sentence of imprisonment. The proportion of Indigenous offenders in custody for firearms offences that carry mandatory minimum sentences of imprisonment rose from 17.5% in 2007–2008 to 40% in 2016–2017. In comparison, the proportion of white offenders decreased from 52% to 41% over the same period, and the proportion of racialized group members who were not Black fluctuated throughout the period, ranging from 6% to 15% of federal offenders admitted for firearm-related offences punishable by a mandatory minimum sentence, depending on the year in question.25

Figure 2 – Proportion of Federal Offenders Admitted for Firearm-Related Offences Punishable by a Mandatory Minimum Sentence, by Race, 2007–2008 to 2016–2017

Source: Figure prepared by the Library of Parliament using data obtained from Department of Justice Canada, “The Impact of Mandatory Minimum Penalties on Indigenous, Black and Other Visible Minorities,” JustFacts, Research and Statistics Division, October 2017.

Because these mandatory minimum sentences of imprisonment disproportionately affect Indigenous, Black and other racialized offenders, these sentences can be expected to exacerbate the problem of over-incarceration among these populations.

Indigenous offenders are significantly overrepresented in Canadian correctional facilities. As of January 2020, Indigenous inmates comprised just over 30% of the adult population in federal correctional facilities even though Indigenous people comprise only 5% of the Canadian population.26 Indigenous women were even more significantly overrepresented, accounting for almost 50% of women inmates in federal correctional facilities as of 17 December 2021.27 The number of Indigenous offenders has increased in the past decade.28 Indigenous offenders are also more likely to be held in custody than non-Indigenous offenders are.29

Black people are also overrepresented in the federal criminal justice system, making up 7.2% of the federal offender population in 2018–2019,30 but only 3.5% of the Canadian population in 2016.31

In light of concerns about the overrepresented Indigenous and Black populations in the criminal justice system, Canadian courts have developed sentencing practices that aim to recognize the impacts of systemic racism and colonialism on Indigenous and Black offenders and promote sentencing without a term of imprisonment, where possible.

Section 718.2 of the Code lists sentencing principles to be considered by the judiciary when determining an appropriate sentence. Section 718.2(e) provides that:

(e) all available sanctions, other than imprisonment, that are reasonable in the circumstances and consistent with the harm done to victims or to the community should be considered for all offenders, with particular attention to the circumstances of Aboriginal offenders.

In R. v. Gladue in 1999, the Supreme Court of Canada acknowledged the “serious problem of [A]boriginal overrepresentation in Canadian prisons”32 and interpreted section 718.2(e) of the Code to explicitly require sentencing judges to consider the particular circumstances of Indigenous offenders, including:

(a) the unique systemic or background factors which may have played a part in bringing the particular [A]boriginal offender before the courts; and

(b) the types of sentencing procedures and sanctions which may be appropriate in the circumstances for the offender because of his or her particular [A]boriginal heritage or connection.33

The use of Gladue reports, which detail these particular circumstances for the courts, has become an established means of informing sentencing decisions that involve Indigenous offenders. The Court, in Gladue, highlighted that

the unique circumstances of [A]boriginal offenders is that community-based sanctions coincide with the [A]boriginal concept of sentencing and the needs of [A]boriginal people and communities. … Where these sanctions are reasonable in the circumstances, they should be implemented.34

While Gladue reports are intended to address the over-incarceration of Indigenous people, some evidence suggests that this strategy has not been particularly effective and that Gladue reports are not universally accessible across Canada.35

Some Canadian courts have also started taking into account the unique circumstances of Black offenders by using impact of race and culture assessments; these assessments provide information about the circumstances of Black offenders in light of the history of anti-Black racism in Canada.36

For offences that carry a mandatory minimum sentence, judges do not have discretion to sentence Indigenous and Black offenders to community-based sanctions, even if a Gladue report or an impact of race and culture assessment indicates that it would be appropriate to do so. However, in contrast to concerns about the disproportionate impact of mandatory minimum sentences on offenders from marginalized groups, some argue that such sentences may protect those in marginalized communities who may be overrepresented among victims of crime by ensuring appropriate sentences for offenders.37 Indigenous people, for example, have consistently been found to more frequently self-report criminal victimization than non-Indigenous people, suggesting they are disproportionately impacted as victims of crime.38

A conditional sentence is one where an offender is sentenced to a term of imprisonment of less than two years, to be served in the community subject to particular conditions,39 rather than in a correctional facility. Since offenders are often required to serve all or part of their conditional sentence in their home, these sentences are sometimes referred to as “house arrest.”40 Conditional sentences are intended to serve both punitive and rehabilitative aims.41 Section 742.1 of the Code sets out limitations42 on their application, allowing it only where:

Clause 14 of Bill C-5 amends section 742.1 of the Code, lifting the prohibition on conditional sentences of imprisonment for offences that carry 10- or 14 year maximum sentences in the situations described above, and for the specific offences previously listed as ineligible for conditional sentencing in section 742.1(f).

Consequently, Bill C-5 makes conditional sentences applicable to a larger number of criminal offences. Furthermore, since Bill C-5 removes some mandatory minimum sentences of imprisonment, persons convicted of these offences are no longer ineligible for conditional sentences.

Some of the limitations on conditional sentences that are removed by Bill C-5 have been subject to constitutional challenges in the courts,43 including an ongoing legal challenge to be heard by the Supreme Court of Canada. In R. v. Sharma, the majority of the Ontario Court of Appeal held that sections 742.1(c) and 742.1(e)(ii) of the Code violated sections 7 and 15 of the Charter.44

Sharma involves a young Indigenous woman, Cheyenne Sharma, who pleaded guilty to the offence of importing cocaine contrary to section 6(1) of the CDSA and received a sentence of 17 months of imprisonment. At her sentencing hearing, Ms. Sharma challenged the constitutionality of the mandatory minimum sentence of imprisonment in section 6(3)(a.1) of the CDSA, and the provision was struck down by the court as a violation of her section 12 Charter rights.45 She also challenged the constitutionality of sections 742.1(b), 742.1(c) and 742.1(e)(ii) of the Code which limit the use of conditional sentences to situations in which:

(b) the offence is not an offence punishable by a minimum term of imprisonment;

(c) the offence is not an offence, prosecuted by way of indictment, for which the maximum term of imprisonment is 14 years or life;

… (e) the offence is not an offence, prosecuted by way of indictment, for which the maximum term of imprisonment is 10 years, that

… (ii) involved the import, export, trafficking or production of drugs[.]

The defence argued that sections 742.1(b), 742.1(c) and 742.1(e)(ii) of the Code deprived Ms. Sharma of her right to liberty under section 7 of the Charter and her right to equality under section 15(1) of the Charter. The sentencing judge decided that sections 742.1(c) and 742.1(e)(ii) did not violate Ms. Sharma’s rights under sections 7 and 15 of the Charter.

The decision was appealed and the majority of the Ontario Court of Appeal held that sections 742.1(c) and 742.1(e)(ii) had a disproportionate and negative impact on the claimant as an Indigenous woman, given the over-incarceration of Indigenous people in Canada and the remedial effect that conditional sentencing can have on over-incarceration.46 It held that Ms. Sharma’s equality rights under section 15(1) of the Charter had been violated. It also held that the impugned sections violated her section 7 liberty rights, as the provisions were overly broad, and consequently, not consistent with the principles of fundamental justice. The infringements of Ms. Sharma’s section 7 and section 15 rights were held not to be consistent with section 1 of the Charter. The Ontario Court of Appeal consequently held that sections 742.1(c) and 742.1(e)(ii) were of no force and effect.

On 14 January 2021, the Supreme Court of Canada granted leave to appeal in this case, and consequently, the final determination as to the constitutionality of these limitations on conditional sentencing is pending.

Canada is experiencing an ongoing public health crisis of opioid overdoses and deaths.47 Opioids are medications that can help to relieve pain; they include drugs such as fentanyl, morphine, oxycodone and hydromorphone. Pharmaceutical opioids are manufactured by a pharmaceutical company and approved for medical use in humans. These drugs are legal when used as prescribed by a health professional to treat pain. Opioids are considered illegal when they have been made, shared or sold illegally. Examples include opioids used by someone other than the person to whom the drugs were prescribed and opioids obtained from someone other than a registered practitioner.48

Opioid use is considered problematic when it has harmful effects on a person’s health and life or when it involves illegal opioids. Problematic use can become a substance use disorder or addiction when it involves regular use despite continued negative consequences.49

Opioid and other drug-related overdose deaths have increased dramatically in recent years.50 Factors that contribute to the crisis include a high incidence of opioid prescribing, the emergence of dangerously potent synthetic opioids like fentanyl and carfentanil in the illegal drug supply, and the impossibility of knowing, without equipment, the quantity of such opioids that has been mixed into illegal drugs.51

Between January 2016 and June 2021, approximately 24,626 apparent opioid toxicity deaths occurred in Canada, and from April to June 2021, there were approximately 19 deaths per day.52 The 1,792 deaths that occurred between January and March 2021 represent the highest quarterly total recorded since national surveillance began in 2016.53

The COVID-19 pandemic has further worsened this crisis, with levels of fatal and non fatal opioid overdoses reaching historic highs.54 The closure of the Canada–United States border disrupted drug-supply chains and has led to the increased toxicity of the illegal supply. Social-distancing guidelines, self-isolation measures, the increased use of substances as a means of coping with stress and reduced access to supports and services have contributed to these historic rates. In particular, social-distancing and self-isolation measures have created situations in which people have died from overdoses alone in their own homes.55

Increases in fatal overdoses have been observed throughout the country, although western Canada remains the most affected region.56 For instance, the British Columbia Coroners Service reported 201 suspected illicit-drug toxicity deaths in October 2021, the highest number of such deaths it had ever recorded in a month. This number represents about 6.5 deaths per day. The data also revealed an increase in the number of deaths involving extreme concentrations of fentanyl after April 2020.57

The drug overdose crisis in Canada disproportionately affects Indigenous peoples.58 Recent figures from British Columbia, for example, showed that between January and May 2020, 16% of all overdose deaths in that province were of First Nations people, who represent only 3.3% of the province’s population. In that same time period, the rate of death among First Nations people was 5.6 times higher than among other British Columbians. In particular, the number of First Nations women who died by overdose was 8.7 times higher than for other women in that province in 2019.59

Moreover, many people dealing with opioid-related harms also experience other mental disorders.60 Factors frequently noted among those who have died of opioid and other drug-related overdoses include: a history of mental health concerns, trauma and stigma; a lack of available help at the time of the overdose; a lack of social support; and a lack of comprehensive, coordinated health care and social service follow-ups.61 In particular, stigma around substance use is a barrier to obtaining help, health care and social services.62

In 2012, Statistics Canada’s Canadian Community Health Survey63 showed that Canadians with a mental or substance use disorder were more likely to be arrested than those without a disorder, and they were more likely to come into contact with police for problems with their emotions, mental health or substance use.64 A report emerging from that survey concluded that “[t]he presence of a mental or substance use disorder was associated with increased odds of coming into contact with police, even after controlling for related demographic and socioeconomic factors.”65

The CDSA regulates certain drugs and associated substances, as listed in the Schedules of that Act. Schedule I lists drugs such as opioids, cocaine and methamphetamine. Schedule II covers synthetic cannabinoids, and Schedule III includes lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), psilocybin and mescaline.

The Narcotic Control Regulations66 (NCR), made under the CDSA, regulate certain narcotics, including oxycodone, opium, codeine and morphine. The NCR outline the circumstances in which activities like possessing those narcotics are permitted.67 Otherwise, where not authorized under the NCR, simple possession of a substance included in Schedule I, II or III is considered an offence under section 4(1) of the CDSA.68 The punishment for the offence of simple possession under that provision depends on the schedule in which the relevant substance is classified. In the case of a Schedule I substance, an offence under section 4(1) can lead to a term of imprisonment not exceeding seven years.69

The federal government’s Canadian drugs and substances strategy is meant to be a “collaborative, compassionate and evidence-based approach to drug policy.”70 It focuses on harm reduction, prevention, treatment and enforcement, among other objectives.

In its legislative responses to the opioid crisis, the federal government has implemented a number of changes. For instance, it has introduced legislation that amends the CDSA to simplify the application process for supervised consumption sites71 and to change offences and penalties for opioid use.72 In 2017, Parliament adopted the Good Samaritan Drug Overdose Act,73 which seeks to encourage Canadians to get help during an overdose and save lives. For people who experience or witness an overdose, this Act may protect them from charges for possession under section 4(1) of the CDSA and for breaches of conditions relating to simple possession of controlled substances.74 The NCR have also been amended to facilitate the prescription of methadone, an opioid substitution treatment.75

Moreover, on 17 August 2020, the Director of Public Prosecutions issued a guideline to prosecutors on the approach to take with simple possession cases under section 4(1) of the CDSA.76 Prosecutors are generally to pursue a criminal prosecution only in the most serious cases that raise public safety concerns. Otherwise, they are to pursue alternative measures, such as Indigenous restorative justice,77 and divert cases away from the criminal justice system. In this sense, “diversion” refers to the approach used to address the conduct of an alleged offender through measures outside of the traditional court process.78 Notably, prosecutors are to consider alternatives to prosecution where the possession relates to a substance use disorder and the alleged offender is “enrolled in a drug treatment court program or a course of treatment provided under the supervision of a health professional, including those involving Indigenous culture-based programming.”79 The guideline recognizes that “substance use has a significant health component” and that criminal sanctions are of a limited effectiveness as deterrents or “as a means of addressing the public safety concerns when considering the harmful effects of criminal records and short periods of incarceration.”80

Bill C-5 contains 20 clauses. Key clauses are discussed in the following section.

Clauses 1 to 8 and 10 to 13 make changes to the Code to remove mandatory minimum terms of imprisonment previously provided for several indictable offences involving firearms or other weapons. The changes made do not change the prescribed maximum sentence for any offences, nor do they impact the designation of an offence as indictable, summary or hybrid.

Clause 2 amends section 85(3) of the Code to remove mandatory minimum sentences of one year (or three years in the case of reoffending) for offenders convicted of using a firearm in the commission of an offence (section 85(1)) or of using an imitation firearm in the commission of an offence (section 85(2)). These offences apply to persons who use a firearm or imitation firearm in the commission or attempted commission of specific indictable offences, or during flight following the commission of such offences.81

Clause 3 amends section 92(3) of the Code to remove mandatory minimum sentences of one year (for a second offence) and two years less a day (for a third or subsequent offence) for offenders convicted of possessing a firearm knowing its possession is unauthorized (section 92(1)) or possessing a prohibited weapon, device or ammunition knowing its possession is unauthorized (section 92(2)).

Clause 4 amends section 95(2)(a) of the Code to remove the mandatory minimum sentences of three years for a first offence and five years for a second or subsequent offence for offenders convicted of possessing a prohibited or restricted firearm with ammunition (section 95(1)), where the Crown elects to proceed by indictment.82 The mandatory minimum sentences of imprisonment removed through this amendment have previously been held to be unconstitutional by the Supreme Court of Canada and are consequently of no force and effect throughout the country.83

Clause 5 amends section 96(2)(a) of the Code to remove the mandatory minimum sentence of imprisonment of one year for offenders convicted of possessing a weapon obtained by the commission of an offence, where the Crown elects to proceed by indictment. Although the mandatory minimum sentence of imprisonment removed through this amendment has previously been held to be unconstitutional by some Canadian courts, it has also been upheld following constitutional challenges by others.84

Clause 6 amends section 99(3) of the Code to remove the mandatory minimum sentence of imprisonment of one year for offenders convicted of weapons trafficking (section 99(1)), except where the object in question is a prohibited firearm, a restricted firearm, a non-restricted firearm, a prohibited device, any ammunition or prohibited ammunition.85 The mandatory minimum sentence of imprisonment removed by this amendment has previously been held to be unconstitutional by a Canadian court of appeal.86

Clause 7 amends section 100(3) of the Code to remove the mandatory minimum sentence of imprisonment of one year for offenders convicted of possession for the purpose of weapons trafficking (section 100(1)), where the object in question is not a prohibited firearm, restricted firearm, non-restricted firearm, prohibited device, any ammunition or any prohibited ammunition.87 The mandatory minimum sentence of imprisonment removed through this amendment has previously been held to be unconstitutional by some Canadian courts of appeal.88

Clause 8 amends section 103(2.1) of the Code to remove the mandatory minimum sentence of imprisonment of one year for offenders convicted of importing or exporting knowing the object is unauthorized (section 103(1)), where the object in question is not a prohibited firearm, restricted firearm, non-restricted firearm, prohibited device or any prohibited ammunition.89

Clause 10 amends section 244(2)(b) of the Code to remove the mandatory minimum sentence of imprisonment of four years for offenders convicted of discharging a firearm with intent (section 244(1)), where the offence does not involve the use of a restricted or prohibited firearm and is not committed for the benefit of, at the direction of, or in association with a criminal organization.90 The mandatory minimum sentence removed by this amendment has previously been subject to unsuccessful constitutional challenges in some Canadian courts.91

Clause 11 amends section 244.2(3)(b) of the Code to remove the mandatory minimum sentence of imprisonment of four years for offenders convicted of discharging a firearm recklessly (section 244.2(1)), where the offence does not involve the use of a restricted or prohibited firearm and is not committed for the benefit of, at the direction of, or in association with a criminal organization.92 The mandatory minimum sentence of imprisonment removed through this amendment has previously been the subject of both successful and unsuccessful constitutional challenges in some Canadian courts.93

Clause 12 repeals section 344(1)(a.1) of the Code to remove the mandatory minimum sentence of imprisonment of four years for offenders convicted of robbery, where the offence is committed with a firearm that is not restricted or prohibited, and where the offence is not committed for the benefit of, at the direction of, or in association with a criminal organization.94 The mandatory minimum sentence of imprisonment removed through this amendment has previously been the subject of both successful and unsuccessful constitutional challenges in some Canadian courts, including courts of appeal.95

Clause 13 repeals section 346(1.1)(a.1) to remove the mandatory minimum sentence of imprisonment of four years for offenders convicted of extortion (section 346(1)), where a firearm that is not prohibited or restricted was used in the commission of the offence, and the offence was not committed for the benefit of, at the direction of, or in association with a criminal organization.96

Bill C-5 also amends the Code to expand the availability of conditional sentences for a wider range of criminal offences.

Existing section 742.1(c) of the Code prohibits the use of a conditional sentence for an offence prosecuted by way of indictment for which the maximum term of imprisonment is 14 years. Clause 14(1) amends this section to lift the prohibition against using a conditional sentence for offences that carry a maximum term of 14 years, and replaces it with a prohibition against using a conditional sentence for three serious offences:

Clause 14(2) repeals sections 742.1(e) and 742.1(f), removing two further limitations on the availability of conditional sentences. The first limitation removed by this clause precludes the use of a conditional sentence for offences prosecuted by indictment where the maximum term is 10 years of imprisonment and the offence: resulted in bodily harm; involved the import, export, trafficking or production of drugs; or involved the use of a weapon. The second limitation removed by this clause precludes conditional sentencing for the following offences, if prosecuted by indictment:

By removing some limitations on the use of conditional sentences contained in current sections 742.1(c), 742.1(e) and 742.1(f) of the Code, clause 14 expands the availability of conditional sentencing. While these amendments mean that conditional sentences are now available as potential sentences for several serious offences, such sentences continue to be prohibited in some circumstances:

An appellate level constitutional challenge has succeeded in Ontario, and leave to appeal to the Supreme Court of Canada was granted, as noted above.98 Consequently, some of the sections of the Code removed by clause 14 may be declared unconstitutional and of no force and effect by the Supreme Court.

Bill C-5 amends the Code and the CDSA to remove some mandatory minimum sentences for offences pertaining to drugs and substances. This bill removes all mandatory minimum sentences of imprisonment from the CDSA. The changes made do not change the prescribed maximum sentence for any offence, nor do they impact the designation of an offence as an indictable, summary or hybrid offence.

Clause 9 amends section 121.1(4)(a) and repeals section 121.1(5) of the Code to remove mandatory minimum sentences of imprisonment for the offence of selling tobacco products and raw leaf tobacco, not packaged or stamped.

Clause 15 amends section 5(3)(a) of the CDSA to remove the mandatory minimum sentences of imprisonment for the offences of trafficking in a substance (section 5(1)) and possession for the purpose of trafficking (section 5(2)). Some of the mandatory minimum sentences of imprisonment removed by this amendment have previously been held to be unconstitutional and struck down by Canadian courts.99

Clause 16 amends section 6(3)(a) and repeals section 6(3)(a.1) of the CDSA to remove mandatory minimum sentences of imprisonment for the offences of importing and exporting a substance (section 6(1)) and possession of a substance for the purpose of exporting (section 6(2)), where the substance in question is listed in Schedule I or II. Some of the mandatory minimum sentences of imprisonment removed through these changes have previously been held to be unconstitutional and struck down by Canadian courts.100

Clause 17 amends section 7(2)(a) and repeals sections 7(2)(a.1) and 7(3) of the CDSA to remove mandatory minimum terms of imprisonment for the offence of production of a substance (section 7(1)).

Clause 20 of Bill C-5 seeks to address the opioid crisis by supporting a public health approach to simple drug possession.101 The same clause adds a new Part I.1 to the CDSA after section 10 on sentencing. This new part introduces evidence-based diversion measures and opens with a new provision, section 10.1, which declares a set of principles. The principles are meant to guide the interpretation of the remaining provisions in Part I.1 and lay out the government’s public health approach to problematic substance use, recognizing that:

Against the backdrop of these principles, the remaining provisions introduced by clause 20 describe the diversion measures that peace officers and prosecutors must consider.

Under new sections 10.2, 10.4 and 10.5, instead of laying charges against a person in cases of simple possession, a peace officer must consider doing nothing, issuing a warning, or with the person’s consent, referring the person to a treatment program. In determining which measure to take, officers must keep in mind the principles set out in section 10.1. However, an officer’s failure to consider those alternative measures does not invalidate any charges that may be laid. Although an officer’s police force may keep records of warnings or referrals made, information about a warning, referral, officer’s decision to take no further action and the offence itself may not be entered as evidence in court of a person’s past offending behaviour.

The House of Commons Standing Committee on Justice and Human Rights amended new section 10.4 of the CDSA so that a police force “shall” (rather than “may”) keep a record of any warning or referral given under new section 10.2 of the CDSA, including the identity of the individual in question. The amendment further states that information in the record may be made available to a judge or court for any purpose relating to proceedings with respect to the offence to which the record relates. The information in the record may also be made available to a peace officer for any purpose related to the administration of the case to which the record relates and to any member of a department or agency of a government in Canada or agent thereof who is involved in administering alternative measures or preparing a report to inform proceedings. Information other than the identity of the person may also be made available to a department or agency that is assessing or monitoring the use and effectiveness of alternative measures.

New section 10.3 establishes directives for prosecutors that are consistent with the guideline issued by the Director of Public Prosecutions. A prosecutor initiates or continues a prosecution for simple possession under section 4(1) of the CDSA only if, after considering the principles set out in section 10.1 of that Act, the prosecutor is of the view that the use of a warning or a referral under section 10.2, or the use of other alternative measures as defined in section 716 of the Code is not appropriate, and that in the circumstances, prosecution is appropriate. Under section 716 of the Code, “alternative measures means measures other than judicial proceedings under this Act used to deal with a person who is eighteen years of age or over and alleged to have committed an offence.”

The House of Commons Standing Committee on Justice and Human Rights added section 10.6 to the CDSA, which requires that any record of conviction for drug possession under section 4(1) of the CDSA that occurs before Bill C-5 comes into force be kept separate and apart from other records of conviction within two years after that day. For a conviction under section 4(1) of the CDSA after new section 10.6 comes into force, the record is kept separate and apart from other records two years after the conviction or two years after the expiry of any sentence, whichever is later, and the person is deemed never to have been convicted of the offence. The amendment allows the Governor in Council to make regulations regarding the use, removal and destruction of such records.

In addition, the House of Commons Standing Committee on Justice and Human Rights added an exception for service providers, such as social workers and medical professionals, so that they are not committing an offence if they have possession of a Schedule I, II, or III substance in the course of their duties and intend to lawfully dispose of it within a reasonable period (new section 10.7).

Lastly, the House of Commons Standing Committee on Justice and Human Rights introduced a requirement for a statutory review of Bill C-5 on the fourth anniversary of its coming into force.

For additional information about sentencing in Canada, see Julia Nicol, Sentencing in Canada, Publication no. 2020-06-E, Library of Parliament, 22 May 2020.

The principles a judge is to take into account when sentencing an offender are listed at section 718 of the Code. Aggravating and mitigating circumstances are characteristics of a case that inform a judicial interpretation of the seriousness of the offence and the offender’s level of responsibility. Aggravating circumstances suggest a greater seriousness and more responsibility, whereas mitigating circumstances suggest relatively lesser seriousness and less responsibility. For a non-exhaustive list of aggravating circumstances, see Criminal Code, R.S.C. 1985, c. C-46, s. 718.2.

[ Return to text ]Ibid., s. 12.

Note that while the most common argument in constitutional challenges of the mandatory minimum is that this minimum violates section 12 of the Charter, some challenges have alleged violations of sections 7 and 15 of the Charter.

[ Return to text ]Ibid., para. 43, citing R. v. M. (C.A.), [1996] 1 S.C.R. 500, para. 80.

For more information about the approach used to determine whether a mandatory minimum sentence violates section 12 of the Charter, see Charlie Feldman, “Mandatory Minimum Sentences and Section 12 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms,” HillNotes, Library of Parliament, 28 April 2015.

[ Return to text ]R. v. Gladue, [1999] 1 S.C.R. 688, para. 74.

For more information about sentencing and Indigenous offenders, see Graeme McConnell, Indigenous People and Sentencing in Canada, Publication no. 2020-46-E, Library of Parliament, 22 May 2020.

[ Return to text ]Although the use of the impact of race and culture assessment was first introduced in R. v. “X”, Canadian courts had already acknowledged the importance of taking into account systemic racism and the particular circumstances of Black offenders in several earlier cases. See R. v. “X”, 2014 NSPC 95. Also see R. v. Anderson, 2021 NSCA 62; and R. v. Morris, 2021 ONCA 680.

For additional information about impact of race and culture assessments, see Maria C. Dugas, “Committing to Justice: The Case for Impact of Race and Culture Assessments in Sentencing African Canadian Offenders,” Dalhousie Law Journal, Vol. 43, No. 1, 2020.

[ Return to text ]Section 85(1) of the Code does not apply if the offender commits an indictable offence under any of the following sections: 220 (criminal negligence causing death), 236 (manslaughter), 239 (attempted murder), 244 (discharging a firearm with intent), 244.2 (discharging firearm – recklessness), 272 (sexual assault with a weapon), 273 (aggravated sexual assault), 279(1) (kidnapping), 279.1 (hostage taking), 344 (robbery) and 346 (extortion). See Criminal Code, R.S.C. 1985, c. C-46.

Although section 85(3)(a) of the Code has been the subject of constitutional challenges, it has been upheld by the courts in several cases. For examples of appellate decisions that uphold the constitutionality of section 85(3)(a), see R. v. Stephenson, 2019 ABCA 453 (CanLII); R. v. Superales, 2019 ONCA 792 (CanLII); and R. v. Al-Isawi, 2017 BCCA 163 (CanLII).

[ Return to text ]For examples of a successful constitutional challenge of section 96(2)(a) of the Code, see R. v. Robertson, 2020 BCCA 65 (CanLII); and R. v. Foster, [2017] O.J. No. 471 (SCJ).

For examples of an unsuccessful constitutional challenge of section 96(2)(a) of the Code, see R. v. Chislett, 2016 CanLII 85360 (ON SC); R. v. Bressette, 2010 ONSC 3831; and R. v. Carranza, [2004] O.J. No. 6041 (SCJ).

[ Return to text ]For examples of a successful constitutional challenge of section 244.2(3)(b) of the Code, see R. c. Neeposh, 2020 QCCQ 1235 (CanLII); R. v. Valade, 2019 ONSC 3033 (CanLII); R. v. Nungusuituq, 2019 NUCJ 6 (CanLII); R. v. Kakfwi, 2018 NWTSC 13 (CanLII); R. c. Vézina, 2017 QCCQ 7785 (CanLII); and R. c. Gunner, 2017 QCCQ 12563 (CanLII).

For examples of an unsuccessful constitutional challenge of section 244.2(3)(b) of the Code, see R. v. Hills, 2020 ABCA 263 (CanLII); R. v. Ookowt, 2020 NUCA 5 (CanLII); R. v. Itturiligaq, 2020 NUCA 6 (CanLII); R. v. Oud, 2016 BCCA 332 (CanLII); and R. v. Crockwell, 2013 CanLII 8675 (NL SC).

[ Return to text ]For examples of a successful constitutional challenge, see R. v. Hilbach, 2020 ABCA 332 (CanLII); and Her Majesty the Queen v. Ocean William Storm Hilbach, et al., 2021 CanLII 18043 (SCC).

For examples of an unsuccessful constitutional challenge, see R. v. Bernarde, 2018 NWTCA 7 (CanLII); R. v. Hailemolokot et al., 2013 MBQB 285 (CanLII); R. c. Perron, 2016 QCCQ 13089 (CanLII); and Caron c. R., 2014 QCCQ 10603 (CanLII).

[ Return to text ]For examples of an appellate-level decision that strikes down the mandatory minimum sentence of imprisonment for the offences of trafficking in substance and of possession for the purpose of trafficking, see R. v. Lloyd, 2016 SCC 13; and R. v. Dickey, 2016 BCCA 177 (CanLII) (sections 5(3)(a)(ii)(A) and 5(3)(a)(ii)(C) of the CDSA declared of no force and effect).

For examples of a lower court decision in which the mandatory minimum sentence of imprisonment for the offences of trafficking of a substance and of possession for the purpose of trafficking is struck down, see R. v. Jackson-Bullshields, 2015 BCPC 411 (CanLII); R. v. Jackson-Bullshields, 2015 BCPC 414 (CanLII) (section 5(3)(a)(i)(C) of the CDSA declared of no force and effect); and R. v. Robinson, 2016 ONSC 2819 (CanLII) (section 5(3)(a)(ii)(A) of the CDSA held to violate section 12 of the Charter, no decision on section 1 of the Charter).

However, in contrast, section 5(3)(a)(ii)(B) of the CDSA has faced constitutional challenges and been upheld in lower courts. See R. v. Carswell, 2018 SKQB 53 (CanLII); and R. v. Boutcher, 2017 NLTD(G) 111, 2017 CarswellNfld 265.

[ Return to text ]

© Library of Parliament