The purpose of the Official Languages Act (OLA) is to ensure respect for English and French as the official languages of Canada. It was enacted in 1969, revised in 1988 and 2005, and overhauled in 2023 to adapt to the legal, technological and sociodemographic realities of our time.

This HillStudy gives an overview of the principles and implementation of the OLA. It also looks at the federal institutions responsible for implementing the OLA, those that are subject to it and recent debates about the legislation. The HillStudy enables parliamentarians and members of the public with a limited knowledge of the OLA to quickly learn more about the federal language regime without delving into its accompanying constitutional, regulatory and policy framework.

The Canadian Constitution does not contain any provisions relating to jurisdiction in matters of language. In a 1988 decision, the Supreme Court of Canada affirmed that the power to legislate in matters of language belongs to both the federal and provincial levels of government, according to their respective legislative authority.1

The first Official Languages Act (OLA) was passed by the federal government in July 1969 in response to the work of the Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism. In 1982, the entrenchment of language rights in the Constitution marked a new era. The OLA was then revised in September 1988 to take into account this new constitutional order. The revised Act expanded the legislative basis for the federal government’s linguistic policies and programs.

The OLA was revised again in November 2005 to clarify the duties of federal institutions with respect to enhancing the vitality of official language minority communities and promoting linguistic duality. Modernization of the OLA was debated frequently in Parliament between 2017 and 2023. Prior to introducing two bills (C-32 on 15 June 2021 and C-13 on 1 March 2022), the federal government held consultations and released an official languages reform document.

Bill C-13, An Act to amend the Official Languages Act, to enact the Use of French in Federally Regulated Private Businesses Act and to make related amendments to other Acts, which received Royal Assent on 20 June 2023, is the most recent update to the OLA.2 This modernization enabled the federal government to adapt the OLA to the legal, technological and sociodemographic realities of our time. Significant changes were made to the principles guiding the Act’s implementation and enforcement. The OLA’s modernization also led to the adoption of an entirely new language regime applicable to the federally regulated private sector, which is not covered in detail in this HillStudy.

The current version of the OLA states that its purpose is to:

(a) ensure respect for English and French as the official languages of Canada and ensure equality of status and equal rights and privileges as to their use in all federal institutions …;

(b) support the development of English and French linguistic minority communities in order to protect them while taking into account the fact that they have different needs;

(b.1) advance the equality of status and use of the English and French languages within Canadian society, taking into account the fact that French is in a minority situation in Canada and North America due to the predominant use of English and that there is a diversity of provincial and territorial language regimes that contribute to the advancement, including Quebec’s Charter of the French language, which provides that French is the official language of Quebec;

(b.2) advance the existence of a majority-French society in a Quebec where the future of French is assured; and

(c) set out the powers, duties and functions of federal institutions with respect to the official languages of Canada.3

The provisions of Parts I to V of the OLA4 have primacy over all other federal legislative or regulatory provisions except those of the Canadian Human Rights Act. The principles underlying these parts, except for Part V, “Language of Work,” derive directly from sections 16 to 20 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.5 Furthermore, the courts have given quasi-constitutional status to the OLA.6

The federal government relies on the OLA to protect the linguistic rights of anglophone and francophone Canadians in their relations with federal institutions, as well as within these institutions themselves. Responsibility for delivering services in both official languages falls on federal institutions and not on the Canadians requesting these services. This is what is called institutional bilingualism.

Although official language programs exist to support learning English or French as a first or second language, it would be incorrect to state that federal legislation aims to make all Canadians bilingual. Rather, the purpose of official bilingualism is to enable the federal government to respond to the linguistic needs of Canadians. This explains why some positions in the federal public service are filled by employees who can serve the public in both languages or in either of the official languages.7

In addition to introducing new objectives related to the protection of linguistic minorities and the French language, the 2023 legislative amendments added four principles to the OLA for interpreting language rights based on case law and sociodemographic realities:

(a) language rights are to be given a large, liberal and purposive interpretation;

(b) language rights are to be interpreted in light of their remedial character;

(c) the norm for the interpretation of language rights is substantive equality; and

(d) language rights are to be interpreted by taking into account that French is in a minority situation in Canada and North America due to the predominant use of English and that the English linguistic minority community in Quebec and the French linguistic minority communities in the other provinces and territories have different needs.8

The OLA now recognizes the diversity of language regimes in the provinces and territories.9 It also recognizes the importance, in addition to ensuring respect for English and French as official languages, of reclaiming, revitalizing and strengthening Indigenous languages, which are the subject of a separate federal statute: the Indigenous Languages Act.10

Lastly, the OLA uses technologically neutral language to define obligations relating to publications, communications and services in all forms: oral, written, electronic, virtual or other.

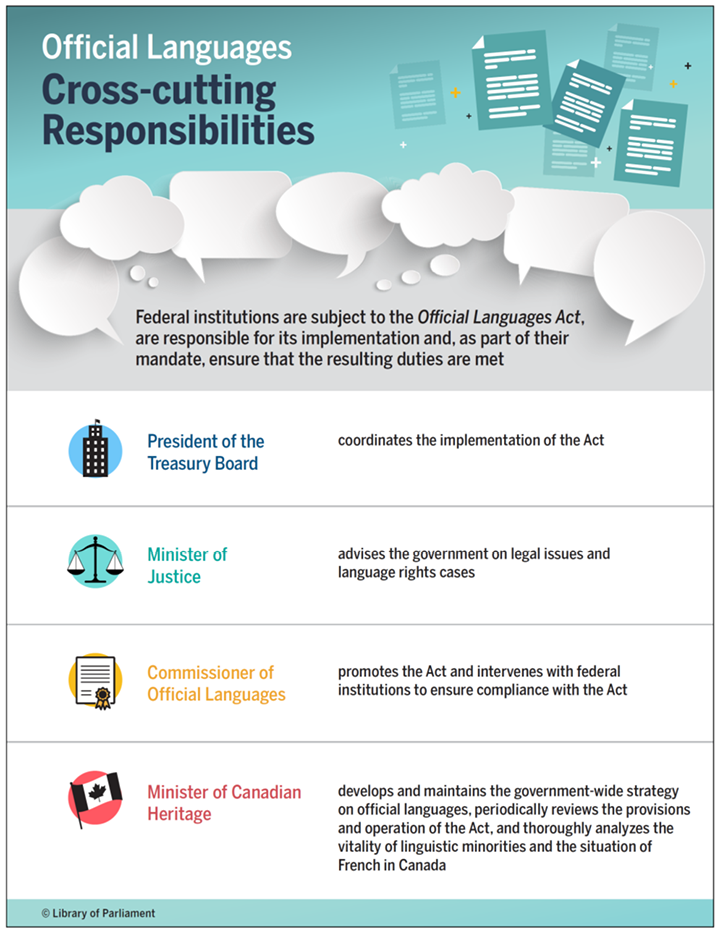

The federal institutions covered by the OLA are responsible for its implementation within their respective mandates.

The commissioner of Official Languages11 is responsible for ensuring compliance with the spirit and letter of the OLA within these institutions, safeguarding Canadians’ linguistic rights and promoting linguistic duality and the equality of English and French in Canadian society. The commissioner is empowered to hear complaints, conduct inquiries and intervene in the courts. He or she tables an annual report to Parliament on the official languages activities carried out by his or her office. The 2023 legislative amendments give the commissioner new powers relating to mediation, compliance agreements, orders and administrative monetary penalties to better enforce the OLA.12 In addition, the commissioner has been given the duty to ensure recognition and respect of the rights of consumers and employees of federally regulated private businesses in certain regions of the country, which is covered by a separate Act, the Use of French in Federally Regulated Private Businesses Act (UFA).13 The commissioner’s new powers will be phased in gradually, as soon as possible or after orders or regulations required by the OLA come into force.14

The Minister of Canadian Heritage15 and the President of the Treasury Board16 also have specific responsibilities with regard to official languages. Their mandates were revised in light of legislative changes in 2023.

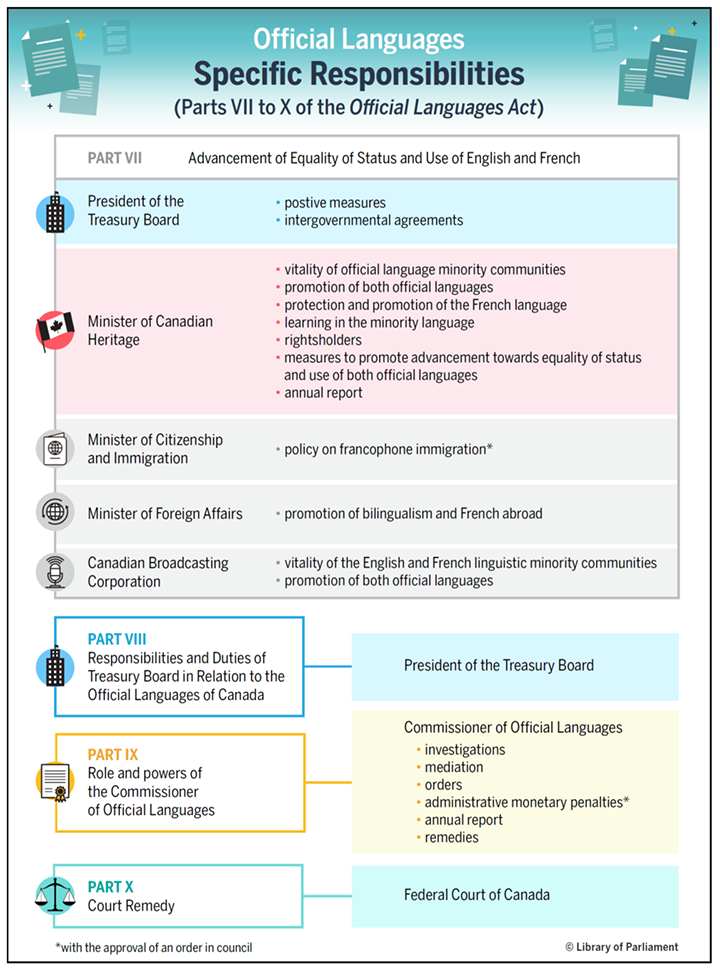

The Minister of Canadian Heritage coordinates implementation of the commitment with regard to advancing the equality of status and use of English and French (Part VII of the OLA) and takes measures that contribute to this advancement in Canadian society. The minister develops and maintains a government-wide strategy on official languages that sets out the Government of Canada’s overall official languages priorities. They report annually to Parliament on their responsibilities under Part VII of the OLA. In addition, the minister undertakes a review of the provisions and operation of the OLA every 10 years and tables a report on this review in Parliament, together with a comprehensive analysis of the enhancement of the vitality of English and French linguistic minority communities and of the protection and promotion of the French language. The Minister of Canadian Heritage is also responsible for promoting the rights set out in the new UFA.

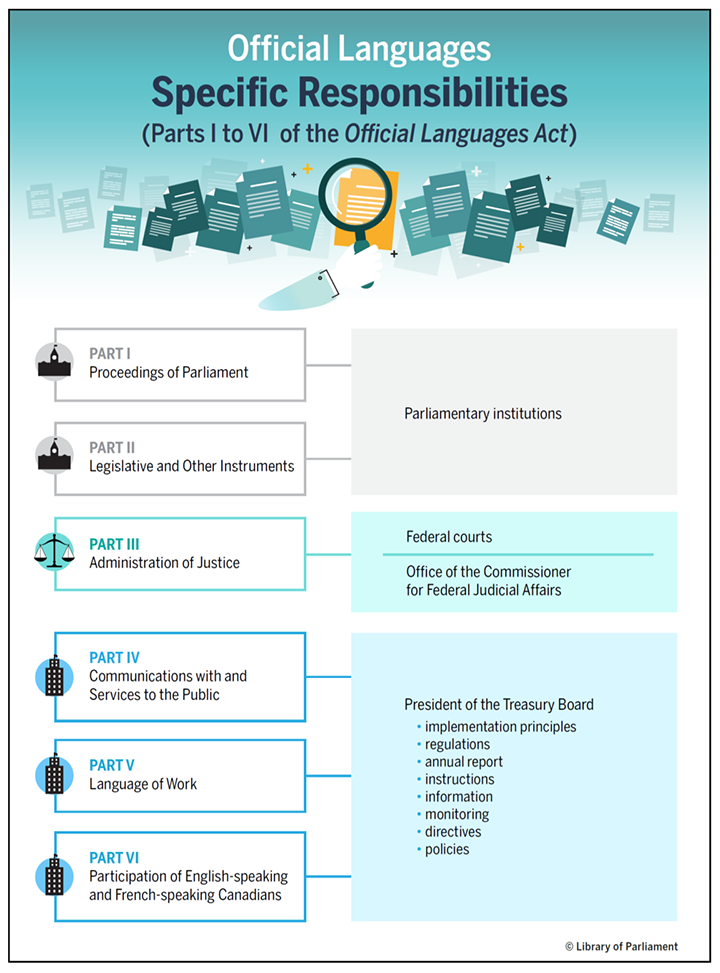

The President of the Treasury Board administers the application, in the public service, of programs related to communications with and services to the public (Part IV of the OLA), language of work (Part V of the OLA), and the equitable participation of anglophone and francophone Canadians (Part VI of the OLA).17 The 2023 legislative amendments gave the President of the Treasury Board new powers with respect to Part VII of the OLA, specifically concerning the taking of positive measures and agreements with provincial and territorial governments. More generally, the President of the Treasury Board is responsible for exercising leadership in relation to the implementation and coordination of the OLA. The President of the Treasury Board reports annually to Parliament on their official languages responsibilities. They consult with the Minister of Canadian Heritage on a number of issues, including the government-wide strategy on official languages and the 10-year review of the OLA.

The Minister of Justice is responsible for advising the government on legal issues relating to the status and use of official languages, preparing the government’s position in litigation concerning official language rights and, at the federal level, administering justice in both official languages (Part III of the OLA). The 2023 legislative amendments set out the responsibilities of the Office of the Commissioner for Federal Judicial Affairs in evaluating the language skills of candidates for the federal judiciary and in providing language training to the judges of superior courts.

In addition, the 2023 legislative amendments assigned specific responsibilities to two other ministers under Part VII of the OLA. The Minister of Citizenship and Immigration, following the issuance of an order, will be responsible for adopting a policy on francophone immigration aimed at restoring and increasing the demographic weight of French linguistic minority communities in Canada. The policy must also recognize the importance of francophone immigration to economic development. The Minister of Foreign Affairs is responsible for implementing the federal government’s commitment to promote bilingualism and the French language abroad.

The OLA also recognizes the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation’s contribution to the vitality of Canada’s English and French linguistic minority communities and to the protection and promotion of both official languages. However, the OLA is not as explicit about the role of other federal institutions, such as the Public Service Commission of Canada or the Translation Bureau, whose expertise contributes to achieving the objectives of the OLA and supports the federal government in its operation.

The following figures present the division of responsibilities for official languages. Figure 1 depicts the cross-cutting responsibilities for implementing the OLA overall. Figure 2 sets out the specific responsibilities for implementing each part of the OLA.

Figure 1 – Cross-cutting Responsibilities with Respect to Official Languages

Source: Figure prepared by the Library of Parliament using information obtained from Official Languages Act, R.S.C. 1985, c. 31 (4th Supp.). [Figure 1 – text version]

Figure 2a – Specific Responsibilities with Respect to Official Languages (Parts I to VI of the Official Languages Act)

Source: Figure prepared by the Library of Parliament using information obtained from Official Languages Act, R.S.C. 1985, c. 31 (4th Supp.). [Figure 2a – text version]

Figure 2b – Specific Responsibilities with Respect to Official Languages (Parts VII to X of the Official Languages Act)

Source: Figure prepared by the Library of Parliament using data obtained from Official Languages Act, R.S.C. 1985, c. 31 (4th Supp.). [Figure 2b – text version]

Since 2003, the Government of Canada has shown its commitment with respect to official languages through five government-wide strategies: the Action Plan for Official Languages (2003–2008), the Roadmap for Canada’s Linguistic Duality (2008–2013), the Roadmap for Canada’s Official Languages (2013–2018), the Action Plan for Official Languages (2018–2023) and the Action Plan for Official Languages (2023–2028). The activities carried out under these government-wide strategies are just some of the many that comprise the Government of Canada’s Official Languages Program and highlight a number of initiatives targeting specific federal institutions. Each year, the Department of Canadian Heritage summarizes the actual expenditures for each of the activities undertaken.18

The Senate19 and House of Commons20 Standing Committees on Official Languages follow the implementation of the OLA and its accompanying regulations and instructions and review the annual reports on official languages submitted by the Commissioner of Official Languages, the President of the Treasury Board and the Minister of Canadian Heritage.21

All federal institutions are subject to the OLA,22 and some are subject to the obligations relating to communications with and services to the public in both official languages, in accordance with the criteria set out in the Official Languages (Communications with and Services to the Public) Regulations (e.g., criteria relating to significant demand and nature of the office).23 These regulations were reviewed and enhanced in June 2019 to offer Canadians a greater range of bilingual services.24 The provisions will come into force in four stages by 2024.

Some privatized corporations – such as Air Canada, Canadian National and NAV CANADA – and third parties providing services on behalf of federal institutions also have obligations under the OLA. The language obligations of privatized corporations are stipulated in their specific enabling legislation, and those of third parties flow directly from Part IV of the OLA.

Federal courts must apply the provisions concerning the administration of justice in both official languages under Part III of the OLA.25 The Federal Court, for its part, is the appropriate court for any court remedy permitted under the OLA, Part X.26

Aside from the Senate, the House of Commons, the Library of Parliament, the Office of the Senate Ethics Officer, the Office of the Conflict of Interest and Ethics Commissioner, the Parliamentary Protective Service and the Office of the Parliamentary Budget Officer, all federal institutions must comply with the policies adopted by the government relating to Parts IV, V, VI and VII of the OLA.27 The official languages policy framework includes the Policy on Official Languages, which is accompanied by three directives that equip institutions to carry out the policy.28 In 2021, the federal government committed to reviewing and implementing new policy instruments following the passage of legislation under Bill C-13.29

The Official Languages Centre of Excellence within the Treasury Board Secretariat and the Official Languages Branch within Canadian Heritage oversee the implementation of the Official Languages Program through reviews prepared by federal institutions on the achievement of objectives relating to Parts IV, V, VI and VII of the OLA. Since 2011–2012, the accountability process has been conducted on a three-year cycle. The form and frequency of reporting vary according to the institution’s size and mandate. Small institutions (fewer than 500 employees) complete a short questionnaire. Large institutions (more than 500 employees) complete a longer questionnaire. Of all these institutions, some 20 are required to submit annual reviews to the Treasury Board Secretariat; some 40 are required to submit annual reviews to Canadian Heritage because of their public-facing role, especially with regard to official language minority communities.

In response to the modernized OLA and the government-wide strategy on official languages currently in effect, the federal government announced investments in a Centre for Strengthening Part VII of the OLA, which will help federal institutions fulfill their responsibilities under that part of the Act. Canadian Heritage will assume shared responsibility for the centre with the Treasury Board Secretariat.30

To help them implement the OLA, federal institutions can count on the support of the Council of the Network of Official Languages Champions and regional federal councils, as well as the National Coordinators’ Network Responsible for the Implementation of section 41.

The OLA does not apply to other levels of government (e.g., provinces, territories and municipalities) or to private enterprises other than those mentioned previously. However, the 2023 legislative amendments specify the terms and conditions for the inclusion of language provisions in agreements between the federal government and provincial and territorial governments. They define the monitoring responsibilities of the President of the Treasury Board and the Commissioner of Official Languages in that regard. In addition, the new UFA sets out linguistic obligations for private businesses in certain sectors (e.g., banking, transportation, telecommunications) and regions (e.g., Quebec, regions with a strong francophone presence).

The OLA has undergone very few changes aside from its revision in 1988. An amendment in 2005 added a duty for federal institutions to take positive measures to achieve the implementation of Part VII of the OLA. Then, following pressure from the public, parliamentarians, government agencies and community stakeholders, the federal government committed to a thorough review of the OLA. Numerous reports tabled in 2019 each made its own comments and recommendations to expand the OLA, strengthen its enforcement, define its implementation mechanisms and provide for a more coordinated approach.31

In her mandate letter published 13 December 2019, the Honourable Mélanie Joly, Minister of Economic Development and Official Languages, was tasked with modernizing the OLA.32 The Minister first released an official languages reform document containing numerous legislative, regulatory and administrative proposals in February 2021.33 The Minister introduced a first bill in the 43rd Parliament, but it died on the Order Paper.34

In her mandate letter released on 16 December 2021, the Minister of Official Languages and Minister responsible for the Atlantic Canada Opportunities Agency, the Honourable Ginette Petitpas Taylor, was given the mandate to reintroduce the bill.35 In January 2022, the Federal Court of Appeal handed down an important decision on the interpretation of Parts IV and VII of the OLA, which delayed the introduction of a second bill in the 44th Parliament so the federal government could take the decision into account.36 Issues during the COVID-19 pandemic also prompted the federal government to include a new reference in the OLA that official language obligations apply at all times, including during emergencies.

When it was introduced in Parliament, Bill C-13 addressed a number of concerns expressed by stakeholders in 2019, including strengthening Part VII of the OLA, reviewing monitoring and compliance mechanisms and defining strategies to ensure respect for the substantive equality of the two official languages. The bill was heavily amended during the legislative process, notably to strengthen the protection of French, halt the decline in the demographic weight of Canada’s French linguistic minorities and reinforce linguistic obligations for high-level positions.

During the 44th Parliament, some OLA principles found their way into other federal legislation. For example, the Broadcasting Act, amended in 2023, sets out new obligations towards official language minority communities, including the requirement for the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission to consult them.37 In addition, amendments were made by the House of Commons to Bill C-35, the Canada Early Learning and Child Care Act, which was still before Parliament at the time of writing, to require that federal–provincial/territorial agreements respect the commitments set out in the OLA.38 In addition, the new UFA draws on several principles in the OLA and extends them to private businesses under certain conditions. Lastly, debates in the Senate during the study of Bill C-13 showed a growing interest in reclaiming, revitalizing and strengthening Indigenous languages, while maintaining strong support for Canada’s two official languages, with special emphasis on protecting and promoting French.39

The OLA is the main piece of legislation governing the implementation of Canadians’ language rights and establishing the obligations of federal institutions in this regard. A constitutional, regulatory and policy framework also exists and has been mentioned briefly in this paper. There have been many calls in recent years for a major overhaul of the legislation, forcing the federal government to commit to modernizing the OLA, which it did in June 2023. The amendments to the principles guiding the implementation of the OLA, and to its compliance and enforcement regime, will gradually come into force. Their implementation will undoubtedly be watched closely over the next few years, leading up to the next revision of the OLA in 10 years’ time.

According to 2022 data, 42% of the positions in the public service were designated bilingual. See Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, Annual Report on Official Languages 2021–22.

Further to legislative amendments made in June 2023, managers and supervisors in federal institutions will have to be able to communicate with their employees in both official languages by 2025.

[ Return to text ]The Action Plan for Official Languages 2023–2028: Protection-Promotion-Collaboration addresses the following federal institutions: Canadian Heritage, Employment and Social Development Canada; Health Canada; Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada; Justice Canada; Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada; Regional Development Agencies of Canada; Public Health Agency of Canada; Canada Council for the Arts; National Research Council Canada; Public Services and Procurement Canada; and Statistics Canada. See Government of Canada, Action Plan for Official Languages 2023–2028: Protection-Promotion-Collaboration.

Details of actual expenditures can be found in the report on official languages that Canadian Heritage submits annually to Parliament.

[ Return to text ]Official Languages (Communications with and Services to the Public) Regulations, SOR/92-48.

The list of offices required to provide services in both official languages is available in the Government of Canada’s Burolis database.

[ Return to text ]Included are administrative or quasi-judicial tribunals (e.g., the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal), the Federal Court, the Tax Court of Canada, the Court Martial Appeal Court of Canada, the Federal Court of Appeal and the Supreme Court of Canada.

For an overview of language requirements for federal courts, see Marie-Ève Hudon, Bilingualism in Canada’s Court System: The Role of the Federal Government, Publication no. 2017-33-E, Library of Parliament, 26 November 2020.

[ Return to text ]Illustration of crosscutting responsibilities with respect to official languages.

Illustration of specific responsibilities with respect to official languages, grouped according to Parts I to VI of the Official Languages Act.

Illustration of specific responsibilities with respect to official languages, grouped according to Parts VII to X of the Official Languages Act.

© Library of Parliament