Temporary foreign workers have been an important feature of Canada’s labour market landscape for decades. In essence, temporary foreign workers are foreign nationals engaged in work activities who are authorized to enter and to remain in Canada for a limited period with the appropriate documentation. In Canada, they are grouped in two overarching temporary labour migration programs.

The first one is the Temporary Foreign Worker Program (TFWP), which assists employers in filling specific labour market gaps when Canadians and permanent residents are not available. The TFWP consists of several major streams, which have diverse requirements and operating procedures. These are:

These TFWP streams require employers to obtain a Labour Market Impact Assessment (LMIA). Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC) will issue a positive LMIA if an assessment indicates that hiring a temporary foreign worker will have a positive or neutral impact on the Canadian labour market. Where an LMIA is required, a positive LMIA must be obtained before the temporary foreign worker can apply to Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada for a work permit.

Over the years, the TFWP, in particular, has gone through a series of reforms, the most significant of which were announced on 20 June 2014. These reforms were intended to limit employer reliance on temporary foreign workers and to strengthen compliance mechanisms to ensure that employers respect program requirements. While the number of approved LMIA applications decreased during this time (with ESDC approving approximately 73,000 fewer temporary foreign worker positions in 2015 than in 2013), starting in 2017, an upward trend has been observed, even though many of the reforms have remained in place. A similar pattern can be seen in the number of work permits issued over the past few years. There are various reasons for this new trend, including a decrease in unemployment rates during this time.

The second temporary labour migration program is the International Mobility Program (IMP), which encompasses streams of work permit applications that do not require an LMIA. This exemption from the LMIA process is based on the IMP’s broader economic, cultural or other competitive advantages for Canada, as well as on the reciprocal benefits enjoyed by Canadians and permanent residents. The number of workers in the IMP has risen consistently over the years, with the international graduates group being the single largest and fastest‑growing component of international mobility. The IMP is significantly larger than the TFWP, with more than twice as many IMP work permits as TFWP work permits coming into effect each year.

Due to a variety of factors, including ineligibility for federally funded settlement services, temporary foreign workers often experience social exclusion in Canada. However, some workers do become permanent residents and Canadian citizens. Temporary foreign workers have opportunities to pursue permanent residency through pathways built into temporary labour migration streams or through separate permanent residency programs that may emphasize Canadian work experience; two examples are the Home Child Care Provider and the Home Support Worker pilots for caregivers. There are also pathways to permanent residency for workers in industries experiencing labour shortages; these pathways include the Agri‑Food Immigration Pilot and the Temporary Public Policy for Out‑of‑Status Construction Workers in the Greater Toronto Area.

Temporary foreign workers in Canada are protected under federal, provincial and territorial labour standards and occupational health and safety legislation. Yet, at the hands of their recruiters and/or employers, many are subjected to different kinds of abuse, including harassment, unpaid overtime, inadequate wages and unsafe working conditions. The federal, provincial and territorial governments have responded by introducing several measures to better protect these workers. At the federal level, the measures have included the introduction of unannounced on‑site inspections, an open work permit for vulnerable workers, and a Migrant Worker Support Network pilot project.

A “temporary foreign worker” is a foreign national engaged in work activity who is authorized, with the appropriate documentation, to enter and to remain in Canada for a limited period. Programs allowing employers to hire temporary foreign workers have evolved in Canada since the 1960s, when the Seasonal Agricultural Worker Program (SAWP) was established to focus on that area of the economy.

Today, temporary foreign workers enter Canada through various temporary labour migration streams with diverse requirements and operating procedures. These temporary labour migration streams are grouped under two umbrella programs: the Temporary Foreign Worker Program (TFWP) and the International Mobility Program (IMP). The TFWP assists employers in filling specific labour market gaps when Canadians and permanent residents are not available, while the IMP covers a wide range of work arrangements (such as those pursuant to international agreements, intra‑company transfers and youth work‑exchange programs) that seek to advance Canada’s broad economic and cultural national interests.1

Over the years, the TFWP, in particular, has gone through a series of reforms, the most significant of which were announced on 20 June 2014.2 These reforms were intended to limit the reliance of employers on temporary foreign workers and on strengthening compliance mechanisms to ensure employers respect program requirements. They included a new labour market verification process (known as the Labour Market Impact Assessment or LMIA) and higher associated fees, specific advertising requirements, a 10% cap on the proportion of low‑wage temporary foreign workers an employer could hire, a four‑year “cumulative duration” rule to limit the time workers could stay in Canada, and a greater range of sanctions (such as listing the names of non‑compliant employers on a public blacklist website).

Most of these reforms are still in place today, although some have undergone modifications. For example, the LMIA processing fee has been eliminated for certain individuals or families hiring caregivers, recruitment requirements for certain streams now put greater emphasis on under‑represented groups facing barriers to employment, and the cap has been frozen at 20% for employers that were program users prior to the introduction of this measure. The cumulative duration rule has been eliminated.3

The present background paper offers a brief overview of the TFWP and the IMP in the aftermath of the June 2014 reforms to the TFWP. It also outlines some relevant policy considerations, such as labour market considerations, pathways to permanent residency, and the role of compliance and enforcement mechanisms. This paper, however, is not intended as a direct comparison of program parameters before and after the June 2014 reforms. Nor does it address the measures announced in response to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‑19) pandemic.4

According to section 95 of the Constitution Act, 1867,5 immigration is a matter of shared federal–provincial jurisdiction. Authorizing the entry and removal of foreign nationals falls under federal jurisdiction, as do issues related to employment insurance and criminal law. Most provinces and territories play a limited role in immigrant selection through agreements for provincial nominee programs that allow them to nominate immigrants to suit their regional interests. Quebec and Nunavut are the exceptions: the former is responsible for immigrant selection and can set its own requirements for employers and temporary foreign workers by virtue of the Canada–Quebec Accord relating to Immigration and Temporary Admission of Aliens, and the latter has no immigration nominee program.6 Further, provincial/territorial legislation protects foreign nationals in matters of employment, education, housing and health care.

The legislation governing the general principles, criteria and authority for immigration decision‑making is the federal Immigration and Refugee Protection Act 7 (IRPA), which is complemented by the Immigration and Refugee Protection Regulations8 (IRPR) with respect to definitions and procedural issues. In addition, the federal ministers both of Employment and Social Development and of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship may issue regulations and Ministerial Instructions in relation to aspects of the temporary labour migration programs. Regularly updated administrative guidelines also help officers working with Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada,9 as well as with the Canada Border Services Agency, to make decisions.10 Finally, under IRPA, the Minister of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship also has the authority to issue special instructions to immigration officers on how applications are to be processed.11

Administration of temporary labour migration programs at the federal level is divided between three departments, as follows:

As mentioned above, the two overarching temporary labour migration programs (namely, the TFWP and the IMP) are each subject to different requirements and operating procedures.

The TFWP consists of several major streams: the high‑wage stream, the low‑wage stream, the primary agriculture stream, the Global Talent Stream, and the Caregiver Program. The TFWP streams require an LMIA.

The IMP encompasses streams of work permit applications that do not require an LMIA,12 including those issued due to international agreements such as the Canada–European Union Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA), and those based on Canadian interests, such as significant social or cultural benefit.13

The LMIA is a labour market verification process, which is used to determine the likely effect that the employment of a temporary foreign worker will have on the Canadian labour market. Employers looking to hire temporary foreign workers under the purview of the TFWP must obtain a positive LMIA.14 ESDC will issue a positive LMIA if an assessment indicates that hiring a temporary foreign worker will have a positive or neutral impact on the Canadian labour market. Once issued, an LMIA is generally valid for a maximum period of six months.15

Along with their LMIA application form, employers must submit certain supporting documentation, such as proof of recruitment efforts to hire Canadians and permanent residents. For employers looking to fill low‑ and high‑wage positions, for example, recruitment requirements include advertising on the Government of Canada’s Job Bank and using recruitment methods that are targeted to an audience with the appropriate education, professional experience and/or skill level required for the occupation, for a stipulated period. In the case of positions in the low‑wage and agricultural streams, employers must also demonstrate that efforts have been made to hire Canadians and permanent residents from under‑represented groups facing barriers to employment, such as Indigenous persons, vulnerable youth, newcomers to Canada and persons with disabilities. Among other reasons, ESDC may issue a negative LMIA if the employer was not able to demonstrate sufficient efforts to recruit, hire or train Canadians or permanent residents for the position.16

The nature and scope of the documentation that is required to support the LMIA application, however, depends on the TFWP stream under which the employer is looking to hire a temporary foreign worker. More stream‑specific requirements are discussed in sections 3.2 and 3.3 of this publication.

Employers must pay $1,000 for each temporary foreign worker position requested in order to cover the cost of processing the LMIA application, subject to certain exceptions. For example, families or individuals seeking to hire a foreign caregiver to provide home care for someone requiring assistance with medical needs are exempt from paying the application processing fee. Exemptions also exist for certain occupations related to primary agriculture. The processing fee will not be refunded in case of a withdrawn or cancelled application or if the LMIA is negative. Further, employers and third‑party representatives are prohibited from recovering the processing fee from temporary foreign workers.17

A work permit, or authorization to work without a permit,18 is required before a temporary foreign worker can be employed in Canada under either the TFWP or the IMP. Where an LMIA is required, a positive LMIA must be obtained by the employer before the temporary foreign worker can apply to IRCC for a work permit. A positive LMIA, however, does not guarantee that a work permit will be issued.19

There are currently three kinds of work permits: employer‑specific work permits, open work permits, and open work permits for vulnerable workers. IRCC and ESDC are also considering introducing an occupation‑specific work permit for temporary foreign workers in the primary agriculture stream and low‑wage stream of the TFWP.20

An employer‑specific work permit (also known as a closed work permit) indicates such details as the name of the employer, the place of work and the duration of employment. The full list of conditions that may be put on a work permit is provided under section 185 of the IRPR. Temporary foreign workers holding an employer‑specific work permit are in theory allowed to change employers, and their employers cannot penalize or deport them for looking for another job. Before a temporary foreign worker can accept new employment, however, the new employer must get permission from the federal government to hire that person as a temporary foreign worker (through an LMIA application), and the foreign national will need to apply for and obtain a new work permit.21 According to IRCC, few temporary foreign workers change employers despite having the option to do so, given the time, effort, cost and other challenges associated with this process.22

By contrast, an open work permit allows a temporary foreign worker to work for any employer in Canada for a specific period. An open restricted work permit may restrict the occupation or location, but not the employer. Although the open work permit contains no restrictions regarding employers, temporary foreign workers with these permits are subject to the general conditions imposed on all temporary residents. Specifically, a temporary resident cannot enter into an employment agreement, or extend the term of an employment agreement, with an employer who is listed as ineligible on the list of employers who have failed to meet their responsibilities under the TFWP or the IMP or who, on a regular basis, offers stripteases, erotic dances, escort services or erotic massages.23 Most workers admitted under the IMP receive open work permits.24

Since 4 June 2019, a new open work permit for vulnerable workers is available to those temporary foreign workers holding an employer‑specific work permit who are experiencing abuse or are at risk of experiencing abuse (defined under section 196.2 of the IRPR as physical, sexual, psychological or financial abuse) in the context of their employment in Canada. This work permit is a transitional measure, meaning that it is designed to provide a pathway for temporary foreign workers to leave abusive situations and find new employment in any occupation. It is therefore exempt from the LMIA process. In addition, family members who are in Canada are eligible for an open work permit if the principal applicant has been issued an open work permit for vulnerable workers.25

The high‑wage stream refers to positions with wages at or above the provincial or territorial median hourly wage.26 When hiring temporary foreign workers through the high‑wage stream, in addition to meeting the recruitment requirements explained above, employers must develop a transition plan describing the activities they will undertake to recruit, train and retain Canadians and permanent residents in order to reduce the employers’ reliance on the TFWP. If an employer applies for an LMIA for the same work location and position in the future, the employer will have to report on the results of the commitments made in the previous plan. There are certain exceptions to the transition plan requirement, including for workers hired in caregiving or primary agricultural occupations.27

The low‑wage stream refers to positions with wages below the provincial or territorial median hourly wage.28 In addition to having to meet recruitment requirements as discussed above, employers are subject to a cap on the proportion of temporary foreign workers they can hire under the low‑wage stream at a specific work location. This cap was introduced on 20 June 2014 as one of the changes implemented to reduce Canadian employers’ reliance on temporary workers. For employers who hired a TFWP worker in a low‑wage position prior to 20 June 2014, the cap is 20%. For employers who did not employ a temporary foreign worker in a low‑wage position prior to 20 June 2014, the cap is 10%. Exemptions from the cap include, but are not limited to, on‑farm primary agricultural positions, caregiving positions in a private household or healthcare facility, and low‑wage positions in seasonal industries that do not go beyond 180 calendar days.29

Certain sectors of low‑wage employment are excluded from the TFWP in areas of higher unemployment. Specifically, ESDC will not process an LMIA application for a position in the Accommodation and Food Services and the Retail Trade sectors when the position is

The primary agriculture stream includes workers in the SAWP and temporary foreign workers from any country engaged in on‑farm primary agricultural work. NOC codes eligible for an LMIA under this stream include both lower‑skilled occupations (e.g., general farm, greenhouse and nursery workers) and higher‑skilled occupations (e.g., farm managers and supervisors).31

The SAWP is designed around specific bilateral agreements with Mexican and Caribbean governments and is intended to provide seasonal employment in agriculture. Under the SAWP, foreign workers are brought in during the planting and harvesting seasons for up to eight months of the year.32 Temporary foreign workers employed under the SAWP sign a standard employment contract that cannot be altered.33

In 2019, a new pathway to permanent residence was introduced for some temporary foreign workers in the agri‑food sector. The three‑year Agri‑Food Immigration Pilot, set to open in May 2020, will be available to individuals who have obtained at least a year of full‑time, non‑seasonal agri‑food work experience under the TFWP. In addition to meeting work experience requirements, participants must also meet language and educational requirements and have an indeterminate, full‑time, non‑seasonal job offer in an eligible occupation.34

The Global Talent Stream was introduced in 2017 as a two‑year pilot under the Global Skills Strategy, and its permanence was announced in Budget 2019.35 The stream is intended to help employers obtain highly skilled or specialized talent more quickly.36 Employers can apply to the Global Talent Stream under one of two categories. Category A requires employers to be referred by an organization on ESDC’s list of designated partners (which includes, for example, provincial ministries of labour, economic development corporations and industry associations)37 and is intended for employers seeking to fill a “unique and specialized position.” 38 Alternatively, employers can apply under Category B, which covers positions included on ESDC’s Global Talent Occupations List (this is a list that identifies occupations that are in demand and that lack sufficient domestic labour supply, such as computer and information systems managers, mathematicians and statisticians, and web designers and developers).39

Employers hiring through the Global Talent Stream must work with ESDC to create a Labour Market Benefits Plan. The plan shows the employer’s commitment to activities that will have a positive and lasting impact on Canada’s labour market and is made up of one mandatory benefit and two complementary benefits. Mandatory benefits differ for employers in Category A and those in Category B: the former must commit to creating jobs for Canadians and permanent residents, and the latter must commit to increasing skills and training investments for Canadians and permanent residents. Complementary benefits might include such activities as enhancing partnerships with local post‑secondary institutions or implementing policies that support the hiring of under‑represented groups. ESDC conducts annual progress reviews of the plan.40

The Caregiver Program creates temporary employment positions for the care of children, elderly family members or family members with disabilities; working in these positions can lead to permanent residence. Created in 1981 as the Foreign Domestic Movement Program, it was known as the Live‑In Caregiver program from 1992 to 2014. Significant changes took effect 30 November 2014, when pilot programs were created for five years. Notably, while live‑in arrangements are still permitted, it is no longer a requirement that caregivers live in their employers’ homes.41 The changes also split the program into two streams, one for caring for children and one for caring for people with high medical needs.42

Individuals who were already working in Canada under a Live‑In Caregiver Program work permit, or whose employers submitted their LMIA application before 30 November 2014, were permitted to remain in the Live‑In Caregiver pathway and apply for permanent residency based on the eligibility requirements of that program.43 They were also permitted to apply for the new streams mentioned above, if eligible.44

In 2019, the federal government launched two new five‑year pilot programs for caregivers (namely, Home Child Care Provider and Home Support Worker), ending the two previous pilot programs. In addition to granting work permits only to those who already meet the eligibility requirements to apply for permanent residency after two years of work experience, these pilots allow caregivers’ immediate family members to obtain work and study permits. As with the 2014 pilot programs, educational and language requirements apply, and there is an annual cap of 2,750 principal applicants per stream.45

Employers hiring caregivers must meet the same program requirements as those hiring under the high‑wage and low‑wage streams. For example, all employers hiring caregivers must meet the prevailing wage for the occupation in the location where the work will take place, and all must follow the high‑ and low‑wage streams’ recruitment and advertising processes.46 However, the Caregiver Program does not share all requirements for these streams, and it is exempt from measures such as the cap on the number of low‑wage temporary foreign workers and the refusal to process applications in areas of high unemployment.47

In 2019, the federal government also introduced a short‑term Interim Pathway for Caregivers. This provided a permanent residency pathway to certain individuals who had worked as in‑home caregivers in Canada, as well as their families. This short‑term pathway was open to individuals who held a valid work permit, had a year of work experience as a home child care provider and/or home support worker in Canada, and met certain language and educational requirements. The interim pathway was initially offered from March to June 2019 and was reinstated for July to October 2019.48

The IMP encompasses streams of work permit applications that do not require an LMIA.49 This exemption from the LMIA process is based on the IMP’s broader, economic, cultural or other competitive advantages for Canada, as well as on the reciprocal benefits enjoyed by Canadians and permanent residents.50 The IMP covers a wide range of work arrangements, including those pursuant to international agreements, intra‑company transfers, youth work‑exchange programs, research‑ and studies‑related work permits, and unique work situations (e.g., airline personnel and United States government personnel). It also includes spouses of IMP participants.51

According to a recent report from the Organisation for Economic Co‑operation and Development (OECD) about immigrant workers in Canada, “the single largest and fastest growing component of international mobility is the international graduates group, who work under a post‑graduation permit.”52 International students, whose numbers have almost tripled between 2008 and 2018, are allowed to work during their studies and stay for up to three years in the country on a post‑graduation permit.53

According to the federal government, the majority of workers admitted through the IMP are highly skilled, earn a high wage, and are mainly from developed countries.54 The IMP is significantly larger than the TFWP, with more than twice as many IMP work permits as TFWP work permits coming into effect each year (see Table 2 in section 4.1 below).55

As indicated above, work permits under the IMP are usually open, because the program aims not to fill specific vacant positions but to advance Canada’s broad economic and cultural national interests, and information on the holder’s intended occupation and destination is often missing.56

Depending on the type of organization, the stream being used, and the nature of the employee’s work permit, an employer hiring a worker through the IMP may be required to submit an offer of employment through the online Employer Portal and pay a compliance fee of $230.57

Using the LMIA to assess the likely effect that temporary foreign workers will have on the labour market is one of the cornerstone features of the TFWP. It is therefore central to any policies affecting the program. The LMIA, however, has to strike a balance between facilitating employers’ access to skills and workers in a timely fashion and encouraging them to invest more in the domestic labour force through, for instance, higher wages, further recruitment or training. One concern raised by subject‑matter experts is that easy employer access to foreign workers could lead to labour market distortions. For example, the use of these workers could limit wage increases, act as a disincentive to employers to seek productivity gains elsewhere (such as through the development of new technology) and take employment opportunities from young Canadians and permanent residents.58

Employers, for their part, have expressed concerns over the delays associated with the processing of LMIA applications for some streams of the TFWP.59 According to ESDC, as of January 2020, the average LMIA processing time for the low‑wage stream was 64 business days, while it was 49 business days for the high‑wage stream.60 Both industry employers and a recent OECD report have called for a streamlining and modernization of the LMIA application process, including through a trusted employer scheme that would grant an exemption to the LMIA requirement.61

Between 2002 and 2013, the federal government facilitated employer access to temporary foreign workers through various measures, resulting in 2,578 employers using temporary foreign workers for 30% or more of their workforce and in 1,123 employers having a workforce composed of 50% or more temporary foreign workers in 2013.62 An audit conducted by the Office of the Auditor General of Canada for the period from January 2013 to August 2016 found that ESDC had not done enough to ensure that employers hired temporary foreign workers only as a last resort. Specifically, the audit concluded that ESDC had relied heavily on information provided by employers about the need for temporary foreign workers and had not considered sufficient labour market information in order to assess whether jobs could be filled by Canadians and permanent residents.63

Following the June 2014 overhaul of the TFWP, which aimed in part to reduce businesses’ reliance on temporary foreign workers, the number of temporary foreign workers admitted per year began to decrease. ESDC approved approximately 73,000 fewer temporary foreign worker positions through positive LMIAs in 2015 than in 2013, with the most notable decreases in the high‑wage, low‑wage, and caregiver streams. The downward trend continued until 2016, after which the number of positions approved through positive LMIAs each year began to increase incrementally (see Table 1).64 This change has been attributed in part to the unemployment rate falling to levels not seen since the 1970s, which, according to government sources, created “challenges for employers who struggled to find enough workers to mee demand.”65 The agriculture sector, for example, was said to experience one of the highest job vacancy rates in Canada between 2015 and 2017, at approximately 7%, which was significantly higher than the national average of approximately 2.5%.66

| 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 151,023 | 198,681 | 162,400 | 104,172 | 89,416 | 87,760 | 97,054 | 108,075 | 129,558 |

Source: Table prepared by the authors using data obtained from Government of Canada, Temporary Foreign Worker Program 2011–2018, accessed February 2020; and Government of Canada, Temporary Foreign Worker Program 2012–2019, accessed April 2020.

A similar trend has been observed in the number of work permits issued to workers under the TFWP over the past few years. That number fell in 2014 and 2015, and then began to rise again in 2016. On the other hand, with the exception of 2015, the number of permit holders under the IMP rose consistently between 2011 and 2019 (see Table 2).67

| 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TFWP | 111,779 | 116,373 | 117,542 | 94,682 | 72,965 | 78,450 | 78,475 | 84,040 | 98,390 |

| IMP | 160,509 | 174,403 | 194,168 | 196,512 | 176,280 | 207,570 | 222,790 | 253,970 | 307,265 |

| Total | 272,288 | 290,776 | 311,710 | 291,194 | 249,245 | 286,020 | 301,265 | 338,010 | 405,655 |

Source: Table prepared by the authors using data obtained from Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada, Temporary Residents, 2011–2014 data, accessed July 2019; and Government of Canada, Temporary Residents: Temporary Foreign Worker Program (TFWP) and International Mobility Program (IMP) Work Permit Holders – Monthly IRCC Updates, 2015–2019 data, accessed April 2020.

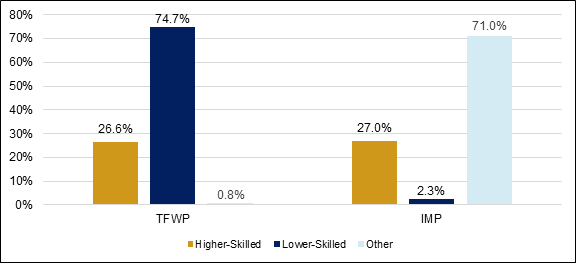

Figures 1 to 4 provide a snapshot of some of the main labour force characteristics of temporary foreign workers admitted into Canada through the TFWP and IMP in recent years.

Among the workers admitted in 2019, TFWP participants held permits mainly for lower‑skilled occupations, while IMP participants were more likely to hold permits for higher‑skilled occupations than for lower‑skilled occupations (see Figure 1).68 This was also a consistent trend prior to 2019.69 Note that this excludes the “Other” category, which refers to workers for whom data on skill level is unavailable. The majority of workers under the IMP are categorized by IRCC as working in this category, especially as most workers admitted under this program receive open work permits.

Figure 1 – Occupational Skill Levels Among Temporary Foreign Worker Program (TFWP) and International Mobility Program (IMP) Work Permit Holders, 2019

Note: Percentages may not sum to 100% because an individual may hold more than one type of permit over a given period.

Source: Figure prepared by the authors using data obtained from Government of Canada, Temporary Residents: Temporary Foreign Worker Program (TFWP) and International Mobility Program (IMP) Work Permit Holders – Monthly IRCC Updates, 2019 data, accessed April 2020.

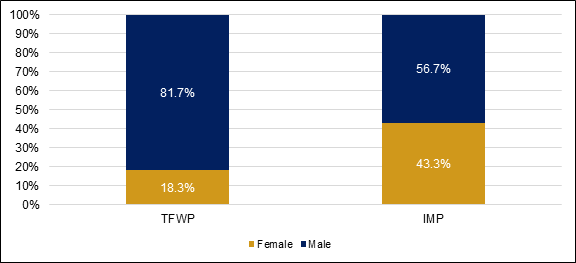

Further, for both the TFWP and the IMP, the majority of work permits that came into effect in 2019 were issued to male workers. The gender gap was more pronounced for the TFWP, with men holding over 80% of the work permits (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 – Gender of Temporary Foreign Worker Program (TFWP) and International Mobility Program (IMP) Work Permit Holders, 2019

Source: Figure prepared by the authors using data obtained from Government of Canada, Temporary Residents: Temporary Foreign Worker Program (TFWP) and International Mobility Program (IMP) Work Permit Holders – Monthly IRCC Updates, 2019 data, accessed April 2020.

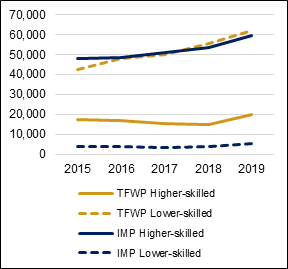

Finally, with regards to occupational skill level, different trends can be observed among women and men; for example, the number of male TFWP work permit holders in lower‑skilled positions rose every year from 2015 to 2019, while the number of female TFWP permit‑holders in lower‑skilled positions remained relatively stable. Instead, for women, the greatest increase was seen in IMP work permit holders in higher‑skilled positions (see Figures 3 and 4).70

Figure 3 – Occupational Skill Levels Among Female Temporary Foreign Worker Program (TFWP) and International Mobility Program (IMP) Work Permit Holders, 2015–2019

Figure 4 – Occupational Skill Levels Among Male Temporary Foreign Worker Program (TFWP) and International Mobility Program (IMP) Work Permit Holders, 2015–2019

Note: Figures exclude work permit holders whose skill level is unknown. While this accounts for less than 1% of Temporary Foreign Worker Program work permits, it represents the majority of permits issued under the International Mobility Program.

Source: Figures prepared by the authors using data obtained from Government of Canada, Temporary Residents: Temporary Foreign Worker Program (TFWP) and International Mobility Program (IMP) Work Permit Holders – Monthly IRCC Updates, 2015–2019 data, accessed April 2020.

The perception of temporary foreign workers – that they fill short‑term job vacancies and then return to their country of origin – has affected policy decisions in Canada. Most notably, as the policy goal is not settlement, temporary foreign workers have not been eligible for federally funded settlement services. The government expects temporary foreign workers to have the required educational, occupational and language skills for their jobs and expects employers to take an active role in helping them settle.71

Due to this lack of settlement services and to other aspects of temporary labour migration programs, temporary foreign workers often experience social exclusion in Canada.72 A number of factors can contribute to the difficulties temporary foreign workers have in participating productively in society and forming relationships with local Canadians and permanent residents. Because lower‑skilled workers generally come to Canada without their families, the social environment they live in is transitory. Long hours of work, linguistic barriers and limited mobility also contribute to an inability to integrate into a community. Isolation is a concern for those working on farms or in remote work camps, as well as for caregivers residing in their employers’ homes.73

Some employers, civil society organizations, communities and provincial and territorial governments have stepped in to provide orientation and settlement support to temporary foreign workers. For example, some agencies that serve immigrants support temporary foreign workers, using funding from sources other than the federal government.74 In other areas, churches and community organizations provide such support as language instruction, transportation assistance and orientation.75 Some provinces allocate funding for settlement services for temporary foreign workers, but support is uneven across the country.76

Integration is an especially important consideration in light of the recent trend toward “two‑step” migration, where economic‑class immigrants first enter Canada with temporary status (as a worker or student) and then convert their status to permanent resident through one of several avenues. Since the 1990s, pathways to move from temporary to permanent status have been created and have been increasingly popular. For example:

In addition, in 2019, the federal government announced new pathways to permanent residency for temporary foreign workers in certain streams and sectors. These have included the Interim Pathway for Caregivers, the Home Child Care Provider and Home Support Worker pilot programs, and the Agri‑Food Immigration Pilot (all mentioned above), as well as the Temporary Public Policy for Out‑of‑Status Construction Workers in the Greater Toronto Area (GTA). Introduced to address labour shortages in the construction sector, this policy will provide permanent residency access to 500 GTA construction workers and their families.79

The federal government has also eliminated the “cumulative duration” rule, which had been in force since April 2011. This rule required temporary foreign workers who had worked in the country for a cumulative duration of four years to leave Canada (or remain in Canada without working) for four years before regaining eligibility to work.80 This measure had the greatest impact on temporary foreign workers (typically from the low‑wage stream) in the year 2015, when those who had been in the country for four years or longer were scheduled to leave. Those who remained were at risk of doing so without legal immigration status.81

Research suggests that when temporary foreign workers experience such difficulties as social isolation, labour standards violations or loss of skills, the effects linger, even if the workers transition to permanent resident status.82 This may have implications for the short‑ and long‑term support that may be needed by those who have experienced such difficulties and become permanent residents and Canadian citizens.83 There may also be policy considerations regarding how to treat temporary foreign workers who wish to become permanent residents but are unable to do so because they do not secure a spot in a given year, or because there is no permanent route for their skill set.

Temporary foreign workers in Canada are protected under federal, provincial and territorial labour standards and occupational health and safety legislation. Among other things, this means having a right to be paid for the work performed, having access to break time and days off work, working in a safe environment and being able to refuse to do dangerous work. Workers who are injured at work, or whose job causes them to get sick, may also have access to provincial or territorial workers’ compensation or to private health insurance provided by their employer. They may also be eligible for Employment Insurance benefits provided they meet the entitlement conditions. Employers of temporary foreign workers in low‑wage positions must also ensure that suitable and affordable accommodation is available. In addition, temporary foreign workers are encouraged to sign employment contracts (outlining working conditions mutually agreed upon) and, as explained above, are in theory allowed to change employers even if they hold an employer‑specific or closed work permit.84

Despite these protections, reports indicate that temporary foreign workers may be subjected to various kinds of injustices, on the work site and off, with those holding an employer‑specific work permit (such as those in the low‑wage stream, the SAWP and the Caregiver Program) being at greater risk of abuse. Examples of abuse include harassment (either physical or verbal), unpaid overtime, inadequate wages, unsafe working conditions and assignment to the most dangerous or least desirable jobs. For those streams where workers live in employer‑provided accommodations, concerns have included substandard housing, crowding and employer control over personal lives during off‑duty hours.85 Research has also revealed networks of extortion, fraud and wage theft at the hands of recruiters and immigration consultants who charge illegal fees with the false promise of a job and even permanent residency in Canada.86

The full scale of human rights violations may even be far greater than the stories reported, as many temporary foreign workers are reluctant to disclose the abuse to which they are being subjected. This may be due to literacy and language or cultural barriers, geographic or social isolation, dependency on employers for both work and housing, fear of not being believed, lack of trust in the authorities that can help them, lack of knowledge of how to report abuse, fear of the abuser’s revenge, and fear that coming forward will negatively affect their immigration status.87

As a result, the federal, provincial and territorial governments have been introducing legislative and regulatory changes over the past few years with the aim of better protecting temporary foreign workers. At the federal level, these have included the introduction of a new open work permit for vulnerable workers, along with the proposal for an occupation‑specific work permit in the primary agriculture and low‑wage streams of the TFWP, as discussed in section 3.1.2 of this publication.88 The federal government has also introduced a Migrant Worker Support Network pilot project with the goal of educating workers about their rights and responsibilities and helping them report wrongdoing, among other things.89

Further, unannounced on‑site inspections have also been introduced. These inspections are undertaken where there is a high risk of non‑compliance with program requirements, and the safety of temporary foreign workers may be at risk.90 Under the IRPA and the IRPR, ESDC has the authority to review employers’ treatment of temporary foreign workers and, where applicable, employers’ LMIA or LMIA application. This can be done through inspections,91 employer compliance reviews92 and reviews under Ministerial Instruction.93 LMIAs may be suspended temporarily while the inspections or reviews are occurring.

Depending on the date and nature of the violation, employers could be subject to a range of penalties under IRPA and the IRPR, some of which were introduced as part of the June 2014 reforms. These include being banned from accessing the TFWP and the IMP for a specific period or permanently for the most serious violations, receiving administrative monetary penalties (from $500 to $1,000 per violation, up to a maximum of $1 million for one year) and/or, where applicable, being issued a negative LMIA for any pending applications or having previously issued LMIAs revoked or suspended. Employers who are found to be non‑compliant as a result of an inspection can also have their name, address, violation and penalty added to a public list administered by IRCC.94

The employment of temporary foreign workers in Canada through various temporary labour migration streams has been a feature of the Canadian labour market for the past few decades, often eliciting calls for changes as governments and policy makers seek to strike the right balance between the interests of employers and those of the Canadian workforce. Along with labour market considerations, policy considerations relating to integration, pathways to permanent residency, and the protection of temporary foreign workers continue to influence Canada’s temporary labour migration landscape.

* This document is an update of a publication by Sandra Elgersma, Temporary Foreign Workers ![]() (547 KB, 20 pages), Publication no. 2014‑79‑E, Parliamentary Information and Research Service, Library of Parliament, Ottawa, 1 December 2014. [ Return to text ]

(547 KB, 20 pages), Publication no. 2014‑79‑E, Parliamentary Information and Research Service, Library of Parliament, Ottawa, 1 December 2014. [ Return to text ]

† Library of Parliament Background Papers provide in‑depth studies of policy issues. They feature historical background, current information and references, and many anticipate the emergence of the issues they examine. They are prepared by the Parliamentary Information and Research Service, which carries out research for and provides information and analysis to parliamentarians and Senate and House of Commons committees and parliamentary associations in an objective, impartial manner. [ Return to text ]

© Library of Parliament